Understanding children: Babies being heard

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 23 April 2024, 6:55 PM

Understanding children: Babies being heard

Introduction

In this course you will find out some of the things very young babies can do. You will also discover how babies can contribute to family life and relationships from birth. You will look at what they need from other adults and children, and what they can learn.

Using a video extract, you will observe and listen to young babies in action, and learn from them.

If you are a parent or carer, you can consider your role in helping to give babies a good start in life.

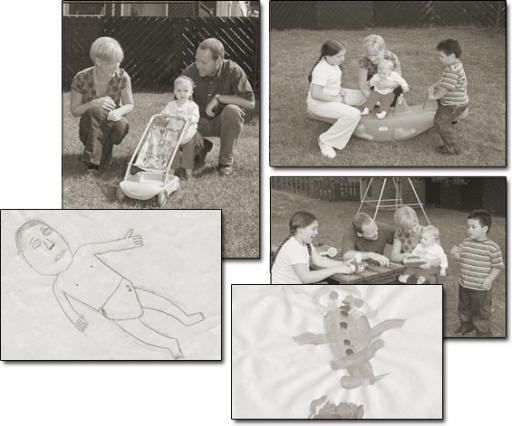

Section 1 will introduce you to the family who are the subject of the case studies throughout the course. The family is fictional, and used as a teaching tool to introduce you to the learning material. Despite being fictional, we hope that its members will become believable figures.

The family is made up from the combined experiences of families and friends and those we know about from our own, and other people’s research.

Jodie Watkins is a part-time recruitment consultant. Her partner is Eamon McLaughlin. They have a 12 month old daughter, Mia. Jodie also has two children from a previous relationship with Graham Adunola, a 30 year old retail manager – Ryan, who is 4 years and 6 months old, and Daisy, who is 10 years and 6 months.

The family extends to include Jodie’s retired parents, Michael and Grace, and Graham’s aunt, Rosalind. All three are retired and in their sixties.

You can find out more in the following PDF: Meet the family

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of level 1 study in Education, Childhood & Youth

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

understand what very young babies can do

understand how adults and older children involve babies fully in everyday life and help them feel value.

1 People right from the start

In this course you will meet the family that you read about in the Introduction and find out some of the things very young babies can do. You will also discover how babies can contribute to family life and relationships from birth. You will look at what they need from other adults and children, and what they can learn. Using video extracts, you will observe and listen to young babies in action and learn from them. If you are a parent or carer you can consider your role in helping to give babies a good start in life.

2 Babies are people too!

2.1 Babies' abilities

You may be studying this course for one or more reasons. You may want to learn more about children out of general interest; you may plan to work towards a formal qualification in the future; or you may have been encouraged to look at the course by friends, family or an employer. You may know quite a lot about babies and children through caring for your own or other people's. In this course you will be finding out about very young babies' abilities, and the ways in which they interact with the world around them. To start you off, the following activity asks you to think about some of the commonly held beliefs about babies.

Study note

Throughout this course you will be asked to pause in your reading and undertake an activity, such as the one that follows this note. Activities are not a test, but they are a central way in which distance learning works. They provide an opportunity for you to stop reading and start thinking, working things out for yourself and deciding what you believe. They are a good opportunity for you to make notes.

Activity 1: babies are …

For this first activity you should read the following comments about young babies. You may have heard them expressed by friends, colleagues, on the TV or in magazines, or they may be new to you. As you read through the list, make a note of the ones that you think are probably true, those you disagree with, and those you feel unsure about.

Young babies can't feel pain.

Babies can't see or hear much when they're newborn.

Newborn babies just sleep all day – they don't need much attention.

All newborns need is to be clean and well fed.

A newborn baby is like a ‘blank slate’ – it can't think at all.

Newborns can express pleasure and displeasure.

Newborns can't tell what's going on around them.

Discussion

How did you get on? In fact the only statement that can really be said to be true is number 6; all the others are either incorrect or very simplified and therefore misleading statements. In number 2, for example, babies’ vision has a short range compared with that of an older child, but this enables them to focus on the face of the carer. The limited vision does not prevent babies from interacting or being aware of the world around them. Such beliefs in babies’ limited capacity were common among many child development experts in the 1950s, and if parents knew different, they didn't have the authority to challenge them.

These beliefs led to circumstances where babies were treated in ways that would be considered inhumane today. For example, the belief that young babies could not feel pain meant that in the past they were operated on without pain-killing anaesthetic – a practice that would now be considered abusive.

The evidence we will consider later in this course challenges some of these views about babies. While it is true that babies’ physical capacities, life experiences and ability to do things without help are limited at this age, it has only been in the last 30 years or so that researchers and others have fully explored just how much very young babies are able to do – that they can express a range of emotions, communicate with adults in quite sophisticated ways, and play a full part in family life. Babies who need to be in incubators after birth are now given frequent contact with their carers, whereas before it was thought that they were ‘too young’ or ‘too ill’ to need stimulation and human contact. Severely disabled babies are not routinely now ‘left to die’ and can develop their own potential. The importance of human contact, love and stimulation for all babies is now well established.

2.2 What are babies able to do?

Activity 2

The extract below is from a book written by UK child development teachers Carolyn Meggitt and Gerald Sunderland. It summarises what the majority of babies less than a week old are capable of.

Read through the extract once. Print the PDF, then, using the list of beliefs about babies’ limitations from Activity 1, write the number beside any statement below which you think disproves it. We have made a start with point (1) for you.

Discussion

From this extract you can see the range of things babies are capable of. In contrast with the statements you considered in Activity 1, you can see that babies have very sensitive skin, they are startled by sudden noises and they respond to the sight of faces, light and high-contrasting patterns. In fact, not only do they have a responsive sense of sight and sound, but they also have a sensitive sense of smell, recognising their own mother's breast. What is also interesting is that babies are beginning to communicate and interact through facial expressions, noises and movements which are made in response to the actions of other people.

‘In his first week I was traumatized and did not notice much. He couldn't see to the best of my knowledge, he hated loud noises and he fed a lot, in fact constantly. He noticed visitors’ voices I think and he recognized me very quickly. I don't know if that was the smell of food or what.’

The examples in the extract above are taken from children (most likely white) brought up in UK cultural traditions. In traditions where babies are kept close to the mother all day and can drink milk when they need to, they may hardly cry at all. Eye contact may also not be encouraged.

So far we have been looking at what ‘most’ or ‘typical’ babies can do, but just as adults are all different, so are babies. In the next section, you will read about the experiences of one family responding to the arrival of an individual baby into the world.

2.3 Mia's first birthday

It is Mia's first birthday. After a birthday tea and before her bedtime the Family sit down with their photograph albums and watch a video made around the time of her birth. The Family look back to that time and share their experiences of birth and what they noticed she could do.

Activity 3: Mia's birth

Read the extracts from the accounts by Mia's Family below. They were asked to think back to her birth and the few weeks following it, and remember what she was like and how they felt. They used video pictures and photographs to help them.

As you read, make notes on what the Family noticed about Mia and:

her range of emotions

her communication and social skills

her need for contact and her use of her senses

the things the Family members noticed Mia doing that might make them want to be with her, and to follow her lead in some way.

You will have come across some of these in the reading you did for Activity 2. ‘Emotions’ refers to Mia's ability to feel happiness, sadness, anger, etc. ‘Communication and social skills’ will include the way in which she lets other people know what she wants and also how she behaves with other people.

When Mia was very young

Discussion

Between them, the Family seems to have noticed many areas of Mia's abilities. They observed her expressing a range of emotions, although they had to interpret these as they cannot know exactly what they were – excitement and anticipation; satisfaction; agitation. They noticed her communication and social skills (following Rosalind with her eyes), her pleasure at human contact (snuggling into Daisy, letting Eamon soothe her to sleep), and her use of her senses. Ryan was even able to get Mia to play with him! Some things noted by Mia's Family as being individual to her are in fact very common: copying someone by poking out her tongue, gripping tightly with her finger, responding to the smell of breast milk and to sounds and bright patterns. The fact that Mia does respond in these common ways is important as it helps her to form relationships with her Family as they delight in and respond in turn to her actions.

Some of the observations of Mia are more likely to be individual to her – did you find any of these? We thought her size may be one – it could be that she just seemed small to Ryan, but if Mia really is a small and delicate baby, then her Family may respond to her more cautiously than if she was chubby and robust. Similarly, from the description we have, Mia appears to be quite an emotionally self-sufficient baby – she settles quickly and does not cry for long if she is not hungry or uncomfortable.

The Family is finding Mia rewarding to be with and already are setting up patterns of communicating with her that are quite individual. For example, poking out tongues may become a game that Mia and Ryan particularly enjoy, Eamon and Mia may come to regularly enjoy bedtime routines together, and Rosalind may always greet Mia by holding out her hand and waiting for Mia to grasp it.

Babies differ from each other from a very early age in what they look like and how they behave, and we have seen that these aspects influence how other people behave towards them. Babies also begin to respond to other people's expectations. People around them may think of a baby in a particular way – as ‘calm’ or ‘strong’ or ‘serious’ or ‘musical’ – and treat them like this whether or not they actually are. When she turns her head to a song, Mia encourages more songs to be sung and may continue to be thought of and behave like a ‘musical’ child. If she is thought of as ‘small and delicate’ by everybody, she may grow used to being protected and may take fewer risks. Sometimes different behaviour is encouraged or discouraged in boys and girls. Researchers at Sussex University in England found adults treated boy and girl babies very differently, depending on whether they thought they were playing with a boy or a girl. The researchers demonstrated this by dressing boy babies in pink and girl babies in blue and observing how adults related to them.

So, the development of babies’ personalities comes from the way in which people react to and interpret very common baby behaviours, and also from what the babies are like as individuals and the way in which these characteristics are reinforced (or not) by babies’ families and the world around them.

To learn about individual babies and what they can do, it can be useful to watch them and think about the way in which they behave in relation to the people around them.

![‘When he was newborn I breastfed on demand and he rarely cried. He let me know he was hungry by “rooting” [open mouth looking for nipple]. By the time he was about three months old he had a “tired” cry which was more of a whinge and an occasional “colic” cry which was more of a shriek!’](https://www.open.edu/openlearn/pluginfile.php/72776/mod_oucontent/oucontent/611/f85642f9/408d472d/y156_2_q003i.gif)

‘When he was newborn I breastfed on demand and he rarely cried. He let me know he was hungry by “rooting” [open mouth looking for nipple]. By the time he was about three months old he had a “tired” cry which was more of a whinge and an occasional “colic” cry which was more of a shriek!’

3 Watching babies

In the next activity you will be introduced to some other babies, all about six months old or younger, who with their mothers are demonstrating some of the things you have read about in the previous section.

Watching babies is a way of getting to know them and what they can do. You can learn a great deal about them by ‘standing back’ and looking. You can do this with babies you know, but here you will be able to watch a video recording. Baby watching – or observation – can help the ideas that you read about babies come alive. It can help you see a wider range of babies than you might do otherwise, and therefore gain understanding of how different they can be.

Activity 4: Video watch

For this activity you will watch a video which has a number of short clips of young babies. They are all with their mothers, but babies are just as able to relate to other adults and older children they are close to.

If you can find someone else to share this activity with – a colleague, friend or adult or child family member – it will allow you to share what you found and compare notes. You don't have to meet up; talking on the telephone or by email can be effective too.

As you watch the video clip try to identify and record the facial and body expressions that show how the babies are feeling. You can use the grid provided in Table 1 to record your observations (we have provided a PDF version for you to download and print). Put a mark in the correct box for each expression noticed. We have filled in the table for James as an example. You will probably need to watch the video clip several times to catch everything the babies do.

Transcript: Video 1

| Expression | Smile/laugh: happiness | Listen/watch | Excitement | Anticipation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| James | ||||

| Alice | ||||

| Sebastian | ||||

| David | ||||

| Rebecca |

There is one more part to this activity. Look at the video clip again. For each baby, look for the times when she or he makes the first move in trying to get communication going. This can be by raising a hand, making mouth movements, or making a sound. Put an initial in Table 2 each time they do this, noting whether it's a hand movement (H), mouth movement (M), or with a sound (S). Again we have provided a PDF version of the table for you to download and print.

| Baby | Initiates communication |

|---|---|

| James | M, H |

| Alice | |

| Sebastian | |

| David | |

| Rebecca |

Discussion

Did you find it easy to watch and write at the same time, or did you have to keep playing the clip over again? It can be hard to concentrate even on a clip that you can stop and start. Doing two or more things at once – watching, interpreting, maybe counting, then noting down – is quite a complex set of tasks. In real-life observation, there are also many other distractions.

Was it easy for you to identify the different facial or body expressions and to attach emotion to it? Certainly, happiness is quite easy to spot, but what about something like ‘anticipation’? Did you think that some babies showed more of one emotion than others?

We noticed how attentive James was, keeping his eyes continually on his mother's face. Alice is very vocal and communicative. Rebecca seemed to be anticipating the toy popping out and got quite excited while waiting. Sebastian makes eye contact and mouth movements to his mother, and David babbles away and initiates frequent conversations.

It was easy to see how the older babies initiated communication. David, for example, was quite vocal and Rebecca was very demonstrative, waving her arms and bouncing up and down. Sometimes it may not be clear that a baby is actually starting off communication, rather than responding to something an adult has started off with them. But did you notice how James, who was only 10 weeks old, raised both hands and made mouthing movements towards the beginning of the clip, and again raised his hand at the end? Although these kinds of movements could be thought of as largely uncontrolled, researchers have found them common and predictable enough to conclude that babies do initiate communication.

An area we didn't ask you to comment on, but is nevertheless important, is the conversations that babies have with their mothers – for example, what Alice's mother was saying when showing her the doll. This kind of talking – where there is exaggerated use of words and syllables and much repetition – is called ‘parentese’ by child psychologists. It is important in that it introduces babies to the patterns in their language and establishes familiar routines for them.

We hope that by watching the babies in the video clip you have seen just how good they are at interacting with adults, and how much they seem to enjoy doing this.

4 Learning and growing

We hope that after completing Activity 4 you will be more aware of how babies have the ability to communicate, initiate conversations and show a range of emotions. Adults and other carers have to interpret what babies need, and provide it. We may not always get it right so need to keep an open mind and be able to change our interpretation and our behaviour if required. In addition, without adults or older children to refer to, a baby cannot learn how to get on in his or her own particular family, community and society.

The help babies need is in many forms; as you have seen already, relationships with other people are vital for babies right from the start. They also need to be provided with food and warmth to keep them comfortable, and things to do and think about to help their minds develop. The Family has lots to say about how they help Mia to learn and grow.

‘Food was his biggest concern so we fed him. I did breastfeed for eight weeks. He was so hungry I was exhausted and had to stop. I suppose we laughed at him a lot and smiled. We cooed and chatted to him a lot.’

Acitivty 5: Helping Mia learn and grow

Read through the comments of Family members below. As you read make notes of examples where people are helping Mia's development. Then write a brief note of how you think each example might help her. Here they are looking back to when Mia was nine months old. You can add any notes you make to your existing notes for future reference.

Discussion

Did you pick out some examples and think of how each might help Mia? Here were our ideas as authors.

Daisy sings, laughs and plays with Mia – this interaction will help Mia learn about communicating and taking turns. She is also learning how to develop speech and language and may even have potential as a great musician!

Eamon is helping Mia learn important lessons about morning rituals, eating and social skills. She is learning about eating as a social activity and through copying her daddy will eventually learn to eat by herself. She is also learning to stop, take stock and reflect on the day she has had, which is a very useful way of ‘letting go’ of a day, dealing with stress and learning from your own experience. It is good for improving the memory too!

Eamon and Michael are providing Mia with examples of men being carers – an important memory to hold on to as she grows up with images of women caring for babies all around her. She is also learning that wheelchairs are fun and a normal part of her life, which may help her to accept wheelchair users playing a full part in her own and other people's lives.

‘Really relaxed, very content! He was not picked up a lot as a baby as I would not let visitors annoy him and I am convinced that it has helped him. I did not let anyone upset me through the pregnancy and it was a good time at work so I think this helped make him relaxed too. His dad is also really relaxed so maybe it's innate!’

5 Promoting development

There are, of course, many ways in which people support babies’ development. The extract in the next activity is from the book by Meggitt and Sunderland and lists some of the other ways in which adults and older children can help very young babies to develop their skills. Some babies with physical or mental impairments will respond to these things in different ways, at their own pace.

Different families will have different ways of promoting babies’ development according to what they know and can manage. You will see that the extract makes certain class and cultural assumptions – for example, that eye contact is a good thing to encourage, that families will have warm housing so babies can lie without clothes on, and that there is enough money around to choose particular baby-attracting furnishings for the home. Families who are part of some ethnic groups prefer to wrap their babies close to the body, and some may not talk to babies as much as others. The suggestions below will only reflect some traditions of what is helpful and will not be the only ways to help babies develop.

Activity 6: Promoting development

Read through the text below. There are two tasks to be carried out, each requiring you to write about 200 words.

Promoting development

Provide plenty of physical contact, and maintain eye contact.

Massage their body and limbs during or after bathing.

Talk lovingly to babies and give them the opportunity to respond.

Pick babies up and talk to them face to face.

Encourage babies to lie on the floor and kick and experiment safely with movement.

Provide opportunities for them to feel the freedom of moving without a nappy or clothes on.

Use bright, contrasting colours in furnishings.

Feed babies on demand, and talk and sing to them.

Introduce them to different household noises.

Provide contact with other adults and children.

(Meggitt and Sunderland, 2000, p.11)

Play

Newborn babies respond to things that they see, hear and feel. Play might include the following.

Pulling faces

Try sticking out your tongue and opening your mouth wide – the baby may copy you.

Showing objects

Try showing the baby brightly coloured woolly pompoms, balloons, shiny objects, and black and white patterns. Hold the object directly in front of the baby's face, and give the baby time to focus on it. Then slowly move it.

Taking turns

Talk with babies. If you talk to babies and leave time for a response, you will find that very young babies react, first with a concentrated expression and later with smiles and excited leg kicking.

(Meggitt and Sunderland, 2000, p.11)

Task 1

Think about the extract above and then write a paragraph about which points you agree and disagree with, and why. Your paragraph should be about 200 words long. You may disagree with what you read because your experience of bringing up children or being brought up was completely different or because some of the suggestions do not seem practical or comfortable for you to do as an adult. You can write about alternative ways you know of helping babies develop, or things you did from the list that worked for you. This is an opportunity for you to practise writing about your own ideas and experience based upon a piece of reading. Don't spend too much time or worry about the result too much – just have a go.

Task 2

Now watch the video clip again and look at your notes in Tables 1 and 2 from Activity 4. Write a second paragraph of about 200 words describing what the mothers in the video did with their babies that appear in the lists of suggestions above.

Discussion

Many of the items listed in the first section help to give babies a sense of security and being loved, which is good for their ability to form close relationships. These suggestions also help babies’ senses to develop and allow them to slowly build up new experiences while in a safe environment. The second set of suggestions can help with their communication skills in listening to language and taking turns to ‘talk’ and listen and to imitate. The object play can help them get used to some of the different shapes and patterns that will form part of their lives – and which may help them with learning to read later on.

Health warning

Reflecting on your early experiences of learning may have brought back memories or strong feelings. This is quite normal and you may find that some materials generate quite strong feelings. If these feelings are uncomfortable or painful you may need to talk to someone about them. You may have a friend or family member who you can talk to but some people find that they would prefer to seek help outside their families.

6 Difference and young children

6.1 Introduction

Earlier in the course, Michael, Mia's grandfather, remarked that all his grandchildren were very different from each other. As authors of this course, we want to cater for the potentially different needs and experiences you have as a student. These experiences can come from a range of origins. For example, the way you approach studying can be to do with your temperament – whether you race through study material or work through it slowly. But it can also be to do with your past experience as a learner – for example, if you were criticised for poor reading in the past, you may lack confidence in your abilities. Babies too are different because of the temperament and personal characteristics they inherit from their families – placidity, seriousness, moodiness. Babies are also different because of the way they interact with and experience the world and people around them once they are born. Some of these differences are even said by researchers to be shaped by what happens in the womb before birth. The expectations placed on them by their families and communities, how they are treated by the adults, siblings and other people who care for them, and the circumstances in which they live, are also very important in shaping who they are. It is a two-way process.

The above discussion relates to an area of interest among academics which is referred to as the ‘nature–nurture’ debate. Academics and researchers interested in the nature–nurture debate are continually exploring how much of our behaviour and personal characteristics is programmed into us at birth and inherited from others (nature), and how much is a product of how we live our lives and the experiences that we have as we grow (nurture). Most researchers in this area would now accept that people's personalities are not formed by only nature or only nurture, but by a combination of both and the way they interact with each other.

6.2 Communicating need

Daisy could tell the difference between Mia's cries quite soon after birth. Some babies may not communicate their various needs quite so clearly as Mia, and carers have to work hard to interpret them. Carers who can make time to watch, listen and ‘be there’ for the baby can try different things, asking others if they are not sure. Most babies will tell you if their needs are not being met – by the way they know best: crying!

Below are extracts from accounts of two babies, observed at the time of their birth. They show very different temperaments, and different parental reactions.

Everyone in the delivery room was struck with how competent and controlled this alert little boy was, moments after birth. His father leaned over, talking to him in one ear. Immediately, Robert seemed to grow still, turning his head to the sound of the voice, his eyes scanning for its source. When he found his father's face, he brightened again as if in recognition … As he was cuddled, Robert turned his body into his father's chest and seemed to lock his legs around one side of his father … By this time, his father was about to burst with pride and delight.

Chris … was one week overdue. His mother knew [he had] not gained [weight] for the past three weeks, but … no one [had] paid particular attention to her comment, ‘He's slowed down’ … When he was first born, the nurse and obstetrician were concerned about his colour and lack of response … Assured by the nurse and doctor that he was intact, their hearts nevertheless sank when they saw his wizened face, with ears which protruded … His mother … began to wonder what she had done to her baby … As he lay wrapped in their arms, he looked peaceful enough. But when he was moved even slightly, his face wrinkled up into a frightened animal-looking expression, and he let out a piercing, high pitched wail. They were relieved when the nurses took him away ‘to take care of him’.

(Berry Brazelton and Cramer, 1991, pp. 76–9; reproduced in Oates, 1994, pp. 201–3)

These extracts are of course selective, and don't show the whole picture of the babies’ births or what happened afterwards. But they provide powerful accounts of these babies’ experiences of birth and the world. They also illustrate how the babies reacted to it at this early stage, and how these reactions had a deep effect on the adults around them and their relationships with the baby.

Although we cannot know exactly what he felt, the account of Chris gives an impression of how miserable and frightened he must have felt, as well as lacking in energy. The hospital's delay in intervening to deliver him when his mother thought something was wrong and the guilt she seemed to feel at his condition when he was born will take time to work through. Chris's experience of the world so far is of something that is alarming and not a safe place. You can see his parents reacting anxiously to him, his appearance of vulnerability and his unsettled behaviour.

On the other hand, Robert doesn't seem worried by the world he has come in to and immediately settles into relationships with his parents and taking an interest in the world around him. This has a reassuring and rewarding effect on his parents and others who meet him.

In case you are wondering if babies like Chris can be damaged by their experiences in hospital, there is some reassuring evidence from a television programme that this is not necessarily the case. A baby who had spent quite a bit of time in an incubator after birth was encouraged to visit the hospital at around two years old to see if it brought back unpleasant memories. It didn't. Of course, it's too simple to draw firm conclusions from this, and the parents had loved and supported the child continually through his experience. But it's worth bearing in mind that early experiences can be compensated for.

6.3 Responding to need

How adults react to babies’ needs will depend on a number of things. These include how relaxed they feel about being a carer and what they have learned from their own childhood about caring for babies. It also includes what is considered to be good childcare practice at the time, wider cultural expectations about bringing up children, and their particular feelings and relationship with the baby in question. A mother or father who has an idea of how they think babies ought to behave and what their baby will be like – for example, that the baby will sleep through the night and will quickly take to breastfeeding – may be disappointed if their baby does not do these things. They may think it's something they are doing ‘wrong’ and their feelings will affect how they treat the baby. Sometimes adults put their own interpretations on baby behaviour. For example, a baby who cries when it's hungry but doesn't get food quickly enough may cry louder and harder. This may irritate its carer who thinks the baby is being ‘naughty’ and may keep the food away for longer to try to ‘teach’ the baby to wait. But the baby doesn't understand what's happening – he or she just wants hunger satisfied and to have attention, so continues to cry. This shows that carers can get into patterns of behaviour with babies that are unhelpful to both sides.

7 Different babies, different families

In the first part of the course we learned that babies can do more than adults think, despite having not been in the world for long. We then looked at how adults and older children can help babies learn and develop. What the extracts have shown is that:

babies’ temperament

how they experience the world

how they behave towards other humans and

how humans behave towards them

all matter, and that babies are a product of them all.

The next activity gives you a chance to think about different babies and their different and similar needs. We also look at the different expectations carers have of babies, and what this might mean for the babies while they grow up.

Activity 7: Babies are different

On the same day that Mia was born, ten other babies were born in the hospital. Two of them were in the room with Mia and Jodie, and Jodie got to know the families while they were there. She collected accounts from them.

Read through the accounts of each baby, and think about the following questions. We have also included the accounts of Mia from earlier.

What individual characteristics do you think each baby has?

What hopes, expectations and concerns do the parents express about their baby?

What do you think each baby needs from its carers? Are there any differences between Mia, Tembi and Harish?

Are there differences in the way Mia, as a girl, and the boys are talked about in the accounts?

Record your thoughts on the chart in Table 3 (which has also been produced as a PDF for you to download and print). We have filled in some points for Mia to get you started, but you may want to add more.

| Baby | What baby is like | What family expect | What baby needs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mia | Tiny, delicate, good at communicating, happy, alert, contented, musical | She will be musical. She will be sociable and enjoy company | Love, attention, time to play, feeding and keeping clean |

| Harish | |||

| Tembi |

What the parents thought

Mia

Harish

Harish is the first-born child of Meera and Jonathan. Meera is a general practitioner in a village practice and Jonathan is self-employed as an architect. Meera is an only child but her parents are from large families and all live quite close by. Harish will have many relatives to get to know. Jonathan's family live in Scotland, where he has five sisters and brothers all living reasonably close to each other. Harish is the youngest of ten grandchildren to his family in Scotland, but the first to his family in England.

Tembi

Tembi is the first-born child of Safiya and Abena. Safiya is a community worker and Abena is studying to be a veterinary surgeon. Tembi will have grandparents and other relatives in London from Safiya's family, and Abena's father is in Liverpool. The couple are active in the local lesbian community and also jointly co-ordinate a group for African women. Tembi has a sperm-donor father.

Discussion

How did you get on? Did you find many differences between the babies?

We noted that all the babies needed attention, comfort, food, shelter, to be touched, and somewhere to sleep peacefully.

We also noticed some differences. Mia is perceived as ‘delicate’ and Harish is described as protesting loudly when he is hungry or uncomfortable.

Tembi comes over as quite demanding and robust. There are often differences in the way babies are described because of their gender. For example, ‘tiny’ and ‘peaceful’ are often used to describe girls whereas a boy might be described more neutrally as ‘small’ or ‘quiet’. Girls are less likely to be described as ‘robust’ or ‘protesting loudly’ as angry or noisy behaviour is generally not encouraged in girls.

One reader commented how she really identified with the mothers of Tembi: ‘My son had so much energy he wore me out. The only way I managed was to have as many people as possible to share his care with me. Luckily, he didn't mind and has grown up to be a really sociable four-year-old.’

All of the families have expectations that their babies will be able to ‘fit in’ with established lifestyles, and this may be more or less difficult depending upon each baby's personality and the particular expectations. Harish, as a baby who quickly expresses discomfort, may find travelling and changes in routine difficult. He may also experience negative reactions to his hearing impairment. Tembi's robust character may help him to forge a strong identity if, as his family fear, he does face prejudice due to being the son of a black lesbian couple. For all of these babies, the development of their personalities will be as a result of a combination of the characteristics that they are born with and the way in which people around respond to them.

8 Conclusion

Young babies can do more than we often give them credit for. From birth they are active participants in life, making sense of their worlds and influencing them.

In this, they need other people to help them, and other children and relatives can play a big part in their lives. Through Mia and her Family's experience of her birth, you have seen the significance of other people to her. You have also been introduced to two other families with babies the same age as Mia. They live in different circumstances and have different expectations of babies. As the families grow up together, they will have to balance and probably adapt these expectations with the reality of living together.

Key points

-

Research has shown that very young babies can communicate, feel and do much more than was believed in the past.

-

Babies benefit from close, predictable and responsive relationships with other people.

Keep on learning

Study another free course

There are more than 800 courses on OpenLearn for you to choose from on a range of subjects.

Find out more about all our free courses.

Take your studies further

Find out more about studying with The Open University by visiting our online prospectus.

If you are new to university study, you may be interested in our Access Courses or Certificates.

For reference, full URLs to pages listed above:

OpenLearn – www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Visiting our online prospectus – www.open.ac.uk/ courses

Access Courses – www.open.ac.uk/ courses/ do-it/ access

Certificates – www.open.ac.uk/ courses/ certificates-he

Newsletter – www.open.edu/ openlearn/ about-openlearn/ subscribe-the-openlearn-newsletter

References

Acknowledgements

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Course image: Kenny Louie in Flickr made available under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Licence.

The content acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons licence). See Terms and Conditions.

Figure 3: Clarissa Leahy/Photofusion;

Figure 4: Bubbles.

Copyright © John Burningham

Don't miss out:

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University - www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Copyright © 2016 The Open University