Learning, thinking and doing

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 19 April 2024, 6:29 PM

Learning, thinking and doing

Introduction

This course has been written because it is all too easy not to take an active approach to learning, thinking and doing, merely reading information but not actively engaging with it. The course itself is a mixture of the theoretical and the practical, the academic and the vocational, and designed to stimulate an active approach to learning, thinking and doing. There is no right way of engaging with the material covered in this course – you have your own reasons for studying it and your own favoured styles of working.

This course deals with the strategies for coping with the demands of learning, but does not cover the tactics required for successful learning. It does not cover specific study skills such as note taking, effective writing or preparing for assignments. If you believe that you need to learn, or brush up on, these types of skills then you are strongly advised to get a copy of The Sciences Good Study Guide by Northedge, Thomas, Lane and Peasgood, 1997, Open University.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of level 1 study in Engineering

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

assess personal learning styles and capabilities, using a learning file in which to record progress

describe the main definitions of learning as a process, and the role played by memorising, understanding and doing

explain the three main categories of theories about learning, namely the acquisitive, constructivist and experiential models of learning

discuss the main conceptions of managing as an activity, and how systems thinking and practice benefit from learning by experience.

1 Learning to learn

This course is about developing your effectiveness as a learner. For example, there are activities which invite you to apply theories to practice and also to criticise theories in the light of practical experience. In these and other ways you will be encouraged to bring your own experience into the study of the course. The idea of asking you to use ideas, not just to remember them, and to bring your own experience into studying, is that they are all ways of developing your ability to learn – as well as being good ways of learning.

There are two main reasons for this emphasis on learning in this course. First, paying attention to how we are learning is an essential basis for learning more effectively. And second, being able to learn independently – setting our own goals, resolving difficulties and monitoring progress – is of growing importance for learning in the workplace as well as in course study. In other words, it is an essential part of putting the thinking into practice.

1.1 Effective course study

Research into how people study effectively suggests that it is important to pay attention not only to the content of what we are trying to learn but also to the process of our learning. Time spent on the process of how you are learning need not be a distraction from achieving your learning goals. It should support your efforts to achieve them.

However, thinking about the process of your own learning is not something which typically forms part of most formal courses of study. Most people probably learn most things without giving a thought to how they manage to learn in the first place. Even failure to learn may not prompt much exploration because so often people conclude that the fault lies with themselves, or the subject, or personal dislike of the teacher. Exploration is avoided by quickly moving to the conclusion that 'I'm no good at maths', or 'history is just boring facts'. I'm sure you can supply your own version of this closing down of the issue.

When we avoid trying to find out why we have failed to learn something there are implications for the long term as well as the short term. In the short term, we abandon a goal to succeed in learning some subject or skill which might have been important to us. In the long term, we learn to live with the idea of accepting failure by judging ourselves or others negatively – we aren't clever enough or the teacher wasn't interesting enough and so on. We do not learn how to sort out what is stopping us from learning and how we might tackle the difficulty with more success. We do not therefore improve our capacity to learn in the future.

1.2 Learning beyond course study

Learning how to learn has become an important goal in higher education. There is a national context in which an emphasis on ability to learn has come to prominence. It is now widely asserted that an ability to learn is as important an outcome of university study as knowledge of a discipline. This is a view put forward strongly by employers, for example, who have an interest in the employability of graduates and the skills they bring into the work place. It is a view which has been reiterated in government reports and in studies of what constitutes 'quality' or 'standards' in higher education.

Furthermore, the speed of change in occupational and social practices requires continual relearning and new learning for most adults, including those with higher education. Detailed knowledge in many disciplines has a very limited 'shelf life' and thus it is much more important to leave initial and higher education equipped with the ability to learn new knowledge and skills when required. A recent survey of several thousand UK companies asked about attitudes to training staff and found that there was often an expectation that employees themselves should take responsibility for keeping up to date and being able to cope with change. Employees were expected often to use their own time and resources to learn new skills and to 'learn how to learn'.

Learning is often referred to as a 'transferable skill' of paramount importance because it is the means through which all other knowledge and abilities are acquired. The arguments in favour of developing an ability to learn thus go deeper than the passing phases of national policy. Analysis, application of general principles, problem solving and so on are all capabilities required for learning effectively both in higher education and in the workplace. It is these various abilities to learn which are now seen as priority outcomes for graduates. Ability to pass examinations does not guarantee that a graduate has a critical grasp of knowledge or can learn 'on the job'. In line with higher education generally, therefore, the learning outcomes of this course emphasise that low-level rote learning is not enough. In-depth grasp of course concepts, ability to apply principles and understanding in diverse circumstances, ability to learn outside the formal course environment – all these goals form part of the aims of this course.

1.3 Reflection and course study

Many of the units on the OpenLearn website include self-assessment questions and activities designed to require you to stop and think, sometimes to take action. This is also true of many Open University courses because Open University course teams typically want students to question what they read and to try out ideas for themselves. Every time you pause to do your own thinking in this way, you are reflecting on what you have learnt.

This course includes several activities that are specifically designed to be reflective. The reasons are as follows.

First, reflection is essential for the development of understanding and of the ability to make use of complex ideas and concepts. Second, it is also essential for raising awareness about how we learn and might improve our learning.

These reasons are the foundation for all the hints and tips about study skills and improved personal communication that you will find in this course – indeed they are not likely to have much effect if you do not combine them with self-reflection and review. Reflection on your own learning is part of this course because it can improve both the quality and the quantity of what you learn, especially if you give yourself time to reflect adequately as a regular part of studying.

Reflection is also something we do spontaneously in everyday contexts, and we may not often notice when and for how long we are reflecting. It may seem unfamiliar, even strange, to reflect as a specific and planned activity. The reason for doing so is because a more strategic use of reflection – giving yourself time to do it regularly and building it into your study methods – enables you to monitor progress, learn from good and bad experiences and plan for better ways of doing things.

More universities are including study skills and 'learning-to-learn' materials in their programmes to encourage students to develop their general learning abilities. Students at the University of Humberside, for example, are provided with a structured programme of learning-to-learn activities which include reflection on outcomes. Reflection is said to be used more often and to better effect by experienced learners. One example of what this might mean in practice is outlined in the scenario in Box 1 'Reflecting on research', taken from the Humberside Learning to Learn Student Workbook.

Box 1 Reflecting on research

Let's imagine that you are involved in a project which involves you undertaking some research with a small group of other students. Your initial view is that trying to do this work as a group is likely to be frustrating and time consuming, so you go off on your own and do the research yourself. However, another member of the group persuades you to come to a group meeting to discuss what you've all found. To your surprise, the others have come across some really useful material that you missed. Furthermore they are quite happy to share it with you, even though you've got very little to give back to them. You end up re-writing your report and getting a very good mark.

How might you reflect upon this experience? Here are three possible scenarios:

-

You decide that you were really lucky, and go out to celebrate your high mark by buying the other group members a drink.

-

You decide that working in groups has its advantages and that next time you will participate in the group right from the start.

-

In addition to revising your views on group activities, you think through how working in this way could be even more beneficial. You decide that although the other members of the group had found some material you had missed, this occurred by chance. What the group should have done is to arrange for each member to have responsibility for researching a different aspect of the topic, and then to collate all the material at the end. You discuss this idea with the rest of the group. Though some of them disagree, you decide to try the idea out in your next group project.

The point of this example is to demonstrate the kind of 'added value' that comes from reflecting more deliberately and with the purpose of finding out what can be learned for the future. There are many different ways of building on the ability we already have for reflection, and the next section describes in more detail the kinds of thinking that reflection for more effective learning requires.

1.4 Defining reflection

Reflection is both an academic concept and also a word in common use, combining ideas of thinking, musing, pondering and so on. This everyday meaning is a good basis from which to start: reflection is very much to do with thinking. However, one of the most important things about reflection is that it enables us to think about our own thinking – about what it is that we know or have experienced. Such reflection might be summed up in the phrase, 'the mind's conversation with itself'.

When we use reflection intentionally, as part of course study, it requires two distinctive kinds of thinking. First it requires the kind of reflectiveness just mentioned. It requires that we direct our attention onto our own thinking and abilities. The aim in turning the spotlight onto ourselves is to become more aware of what we already know and can do, more aware of the inter-relationships between our existing ideas and actions and their values for us. This kind of reflection is essential in reviewing for ourselves the significance of the learning we are engaged in, its outcomes for us and the impact it makes on what we want to learn in future. We need to think reflectively, for example, if we want to clarify our motives for learning, what we want from course study and the extent to which our goals are being achieved.

The second kind of thinking that reflection requires is critical analysis of ideas and experiences, so that meanings are questioned and theories tested out. Such thinking may require a framework of questions or some problem-solving activities to help you compare and contrast arguments and frameworks. Indeed, both reflectiveness and critical analysis require the learner to be active, not only paying attention to the content of course materials but also working independently with the concepts introduced. This requires willingness to regularly turn away from the course materials in order to formulate a personal response, and to use your own words and constructions.

Reflection is an important component in all kinds of learning, but particularly in the kinds of study required for academic understanding and for the development of skills such as effective communication, problem solving and so on. Understanding requires the integration of new knowledge into what we already know. Our existing knowledge is stored in memory in ways particular to the person and to their experience. My understanding of 'learning', 'unemployment' or 'technology', for example, will not be exactly the same as yours, or that of my colleagues. There will be meanings, images and details associated with these concepts which are particular to me, and a product of my personal history and educational experience. Even so, there will also be ideas and feelings which are generally associated with these terms, and a core of meaning in common which enables me to communicate with others about them. In other words, the knowledge that we have has both unique features in the way we understand and remember it, and yet enough common currency that we can usefully share at least some of what we know with others.

When we are learning a new topic, we need to spend time putting new material into our own words, trying out new ideas, using what we already know, and seeing where the new material 'fits in'. This process may also lead us to question our existing knowledge and values, of course, and to create new frameworks of understanding which reconcile both old and new. We need to reflect more often on new material than when we are learning or reading about something with which we are already familiar. This is because we need to build 'bridges', in ideas, diagrams or images, between what we know already and what we are trying to understand and remember.

Understanding is an active process of constructing meaning. Reflection has a vital role to play because it is the process whereby we become aware of what we are thinking and able to change and adapt our ideas and understandings to take into account new learning.

1.5 Making the most of your reflections

The value of the work you do on all the activities in this course will be strengthened if you can keep track of it and follow the development of your own ideas as they build up. It helps to keep your notes in one place, together with other material which catches your interest for its relevance to the subject, such as newspaper cuttings, journal articles and reports, and so on. The place where you keep them may be a box file, ring binder or anything else that suits your preference. Whatever you use, it provides a tangible reminder of the learning process you are engaged in. I shall refer to this collection as a 'learning file', and suggest that you use it to work on activities of all kinds throughout the course.

The completion and return of each of your assignments could also be used as an opportunity for self-review and planning, recorded in your learning file. The questions you ask yourself about the grade and the reasons for it are a necessary basis for self-review and action planning. You should also use the opportunity to follow up with further research if you are left with uncertainties about your work or the areas in which you need to improve.

While studying this course you may also decide to build up a 'virtual' learning file on your computer, by setting up a special file on your hard disk where you record activities and reactions to what you have studied. The OpenLearn Comments sections can also provide a very valuable opportunity to find out about other learners' reactions and to stimulate your own thinking (but too much of it can also be time consuming and confusing – a proper balance is needed). You might find it convenient to build up both a computer-based learning file and a hard-copy learning file, each complementing the other.

You will find more suggestions for building up a learning file of this kind in Box 2 'Setting up a learning file'. If this is an idea you are already familiar with, and keeping a log of your own learning appeals to you, then you can now see how your approach is a strength you can build on. If you are not used to organising your work in this way, remember that the idea of a learning file is to create a 'thinking space' for active reflection on your learning. It can take whatever form you prefer and which is most likely to stimulate you to take an active approach to study. You might like to use the self-review activities below, entitled 'Building on strengths' as a first entry in your learning file.

Box 2 Setting up a learning file

A learning file is a way of making the time and space to think about what you are learning and how you are learning. It should help you to reflect critically during the study of your course and to get the most out of the efforts you put in. It's something you are in charge of, to use for yourself. It need not be something you discuss with your tutor, or indeed anyone else, though it may help you structure your work more productively, building up to the assignments.

Tips for keeping your own learning file:

-

Your learning file may be a ring binder, a box file or a folder of some kind – the important thing is that you have a place where you build up your own ideas and abilities and which is organised so that you can use it for your own self-review and development. Your learning file may include your work on the activities, reactions which relate to course issues, drawings/diagrams, newspaper cuttings, notes on the subject that you are studying and so on.

-

If you are not used to this way of working, try to make a start at the beginning of the course and find a way of building up your reflections and other material which fits with your approach to study. You can use the activities in this and other related units as the starting point. This should create the stimulus for you to work on questions and activities which you set yourself.

-

Your learning file is for you. Its value is for capturing thoughts and ideas while you are still working things out, or coming to terms with new ideas and reactions. Don't try to write the kind of organised text which you might use in an assignment or essay. You might make more discoveries about your learning if you are spontaneous and don't inhibit the flow of your thinking by concerns with grammar or structure.

-

Try to set aside a few minutes at the end of your study time, for looking back through your entries and reflecting on the development of your own ideas and interests. You might do this once or twice a week. Your learning file is a place for you to review your own progress and whether you are getting what you want out of course study.

-

Whether or not you are naturally an organised person, it does help to date your entries and to keep careful page references or cues to audio and video material which prompted your thinking. This will enable you to go back to course materials if you need to at a later stage. A learning file is obviously a useful activity from the point of view of revision prior to the exam. It encourages you to digest the course as you go, and to build up a framework of personal understanding. If you have been able to do this during the course, you are less likely to feel overwhelmed by how much there is to revise at the end.

1.6 Building on strengths

Activity 1

A self-review exercise for your learning file

The aim of this activity is to encourage you to take a problem-solving approach to your own learning, and to be proactive. The first part asks you to reflect on your reasons for studying this course and the second part to reflect on prior learning experiences and issues.

Part 1

Think back over the aims of this course that you read in the learning outcomes section. If you need to, go back to the start of this course and refresh your memory of what these are. Now, put these to one side and think about what you personally want out of studying this course. Try completing the unfinished sentence below in your learning file, adding your own reasons for studying the course:

I am studying this course because:

1.

2.

3.

4.

Part 2

Using the tabular format set out below in your learning file, list some relevant prior experiences and issues in the first column and then note your strengths and weaknesses in that area in the next two columns.

| Prior experiences or issues | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Personal qualities, e.g. determination, being organised, etc. | ||

| Study skills, e.g. essay writing, effective reading, etc. | ||

| Motivation, e.g. interest in subject, strong, weak, etc. | ||

| Circumstances, e.g. lack of space to study, access to a computer, etc., and how you handled them |

Having recorded your reasons for studying, you need to reflect on what factors might help or hinder your achieving your goals. First there is the subject itself. There may be some areas of study, or some of the course aims, which you know you will find difficult or challenging. You are more likely to meet the challenge by thinking ahead and looking for ways and means of helping yourself through that aspect of the course. Then there is the range of teaching resources available, some print-based, some audio-visual and some computer-based. Which do you prefer to use? Which are most difficult to use?

Second there is the experience you bring to the course. Reflection on prior learning experiences is important not only to review past achievements, but in order to plan new learning goals and to think ahead about how to avoid familiar or predictable problems. Having read this far, you should have some idea of what this course is about and what it will require of you. Think of your existing experience of study and note where you think your strengths and weaknesses lie in Table 1 . It might help to think about a concrete example, such as a course you studied recently, rather than study in general. If you find the tabular format a constraint, list your strengths and weaknesses in any way that suits you.

My guess is that a few minutes spent reviewing your prior experience of study will bring to mind learning strengths and weaknesses which will be relevant for this course. In Tables 2 and 3 are two examples from other Open University students who have tried this exercise. In spite of their strengths – being organised, well motivated, determined and so on – they also found weaknesses that would be likely to affect them during this course. The first student (Table 2) noted her concentration span was short, and that her interest levels varied from block to block. But even factors such as concentration can be affected by action we take ourselves.

| Column one | Column two strengths | Column three weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Personal qualities, e.g. determination, being organised, etc. | Well organised. | Easily distracted Concentration span short. |

| Study skills, e.g. essay writing, effective reading, etc. | Writing OK. | Reading patchy. |

| Motivation, e.g. interest in subject, strong, weak, etc. | Interest varied from block to subject matter. block. | Fairly strong interest in most |

| Circumstances, e.g. positive or negative and how you handled them | Support from partner. | Time a problem. |

| Column one | Column two strengths | Column three weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Personal qualities, e.g. determination, being organised, etc. | Determination – commitment and self-discipline to give up things I like doing to get the job done. | Inability to rise early to allow more time for study. |

| Study skills, e.g. essay writing, effective reading, etc. | Will work harder early in course to be ahead in case unforeseen circumstances cause distraction. | Cannot LEARN under pressure or against the clock. Take too many unnecessary notes. |

| Motivation, e.g. interest in subject, strong, weak, etc. | Enjoy tackling a subject and overcoming difficulties in learning. | Unsure that I have overcome the difficulties despite good marks. |

| Circumstances, e.g. positive or negative and how you handled them | Can prioritise when my job/family/friends require more of my time. | Sometimes forget to enjoy myself. |

People lose concentration often when their interest in what they are studying wanes, or when they are not really clear about why they are studying something. Reading without wanting to find out is very likely to slip into a passive routine from which you learn nothing. Both concentration and interest levels are high if you have some questions in your mind which the text should answer. One way round the concentration problem, therefore, could be to set yourself a question or two to answer – perhaps even skimming the text to find answers before you read it from beginning to end.

It is also helpful to set specific goals for yourself – with time limits – so that study tasks do not stretch endlessly into the future. You might decide, for example, to study only the conclusions and summaries of something you know is of little direct interest to you, thus cutting down on study time for that part of the course. This is not a strategy to use frequently, of course. Often it is not possible to achieve what is required within set time limits, but it can be a useful strategy to help you focus on achievable targets. It should at least enable you to learn the key ideas and thus avoid the kind of study where you feel the ideas are just washing over you.

In the other student's comments (in Table 3) there are also potential weaknesses that could be tackled in advance of their becoming a problem. Taking too many unnecessary notes for example. Why does that happen? It could be because the student does not find it easy to sort out what are the key ideas in a chapter or block of learning material. One difficulty students find, for instance, is separating the arguments in a text from the examples and from illustrative material which is less important for note taking. It might help to try out an exercise doing just this with one section, choosing one which is obviously essential for the course's aims. There are many guides on note taking, such as those in The Sciences Good Study Guide, and these could be looked at before studying the section and taking minimal notes. These notes could be reduced to no more than, say, one side of A4.

Study strategies such as these will not transform difficulties overnight, but they do offer the chance of improvement and a gradual accumulation of more confident and effective approaches to learning. They can help make good practice (such as reading with some questions in mind) a matter of routine. They can help build confidence, for example in your ability to make judgements about what is important and needs noting, versus what is not. Learning is a skill, and, like all skills, practice with feedback is key to improving on performance.

On a course with computer conferencing, there are even more possibilities for finding ways round study problems. Many students enjoy finding out what causes problems for other students and are happy to explain how they tackle things. Messages posted to a relevant course conference could ask for ideas about familiar study problems, or for comments on notes (which could also be posted). These are likely to generate a raft of ideas, one or two of which may be really useful for you. You could take responsibility perhaps for initiating topics which keep the issue of study 'hints and tips' alive, even summarising some of the themes if that seems useful.

It is appropriate that the last words on 'learning and reflection' should go to you. I've reproduced in Boxes 3 and 4 below two very different reactions to a course – not in this case an Open University undergraduate course but one taught completely online. One student found the experience very positive and rewarding, the other did not. Would it have helped both these students if they had spent a little time in advance to reflect on:

-

their learning goals,

-

how to use their strengths and weaknesses as a learner?

Consider both these questions as you read through their comments, and take a minute or two to reflect on your answer. My own thoughts conclude this reading.

Box 3 Alan – A positive experience

I have learned an enormous amount over the past three months and am extremely grateful to the team for setting up such an excellent learning environment. Thanks also to my peers on the course. Without them I don't think I would have come this far.

I began the course sceptical about the ability to provide genuine interaction using computers. I was proved wrong. I have developed some excellent online friendships over the past three months and have felt very close to all my colleagues on this course.

I began this course wondering if true collaborative learning could take place online. I have been shown it can with the right mix of people. This particular group appears to have worked very well together. We have supported each other and this has greatly aided the learning process. Is this typical of all courses? Have you ever moderated a course where the mix of people was wrong and therefore the interaction not successful? This must have a huge effect on the learning and enjoyment of the course.

I began this course wondering if I had anything to contribute, and finish happy in the knowledge that no matter what your background or expertise everybody has something to contribute in conference. At times I had no idea what was being discussed but by expressing my ignorance I hope I helped others who may have felt the same and I also hope I helped those who were in the know to express themselves in layman's terms. This certainly happened to me when I got too involved in my own specialist area. I was asked to explain again, a most useful exercise !!

I began this course wondering how I would fit it in with my other work and family commitments but found the medium provided great motivation and interest. I was always keen to log in and interested to read the messages. I had to put a lot of time in the early stages but this was to my own advantage and as I have said to you earlier, the more I put in the more I got out. To my great regret I have not been able to contribute as much over the past few weeks and this has been to my distinct disadvantage. I have been logging in regularly and reading the messages posted but I just have not had the time to reflect and to post my own comments. I realise I am not alone in this but I do get frustrated when I cannot put my all into something !!

I began this course disliking writing and I finish this course a better communicator by text. I have always preferred communicating orally and face to face. This course has shown me it is possible to communicate via text, and that writing can be enjoyable.

Box 4 Janet – not so happy

The medium is not as asynchronous as it seems. If a bit of time is missed it is hard to catch up. You feel an observer of someone else's conversation. Before making a point you wonder if it has already been made and so have to read back – by the time you are ready the debate has moved on. It is therefore necessary to log on regularly – perhaps every day. This is especially true of collaborative work where your time and the other participants' time have to mesh together.

It is a cold medium. Unlike face to face communication you get no instant feedback. You don't know how people responded to your comments; they just go out into silence. This feels isolating and unnerving. It is not warm and supportive. Perhaps smaller groups would have helped.

Writing does not come easily to me. I don't enjoy it. I find it easier to speak. And reading on screen is difficult; it is harder to get the real point than for printed text.

This course requires self-discipline. It is too easy to drop out. If you don't log on you lose contact and get no reminders. Perhaps another form of communication is needed as well.

We could have benefited from a longer familiarisation period. Perhaps the first exercise could have been something not too serious. Perhaps a conference discussing how to conference, when to do it, how to deal with the amount of data etc.

Special learning skills are needed for conferencing. For example: how to filter the vast amount of contributions. Perhaps these special conferencing skills should be taught.

1.7 Conclusions

Could both of these students have got more from their involvement with the course if they had taken time to reflect on their goals and their strengths and weaknesses, especially at the beginning of study? Alan, whose reaction to the course was positive, for example, could have learned more about how the course succeeded if he had reflected rather more in the beginning about his initial scepticism and his preference for communicating verbally rather than in writing. What was the reason for his attitudes and what was it about writing that he found difficult? Although the course has changed his views and his abilities to some extent, he seems to put some of the outcomes down to chance. Could it have been only the chance of a friendly group with good natural dynamics that made the course worthwhile – and if so what has he learned that will transfer to other comparable situations? He might have been able to identify more reasons for the success of the group and the course in stimulating his interest in writing if he had recognised that the development of writing skills was one of his reasons for doing the course in the first place – and if he had set himself a plan for pursuing this goal explicitly through study of the course.

For Janet the course has been a failure and she dropped out. She might have avoided that if she had given herself more time at the beginning to recognise the mismatch between what she felt her strengths and interests were, and what challenges she would probably face on a course taught through conferencing (as this was). Disappointment and drop out were not the only possible outcome. She could have decided to contact her tutor at the earliest sign of problems to ask for help. Her tutor could have advised her on strategies for coping with the backlog of messages, and might have given her confidence to contribute, if only irregularly.

If feeling in touch was a strong need, she could have found a fellow student to work with as a pair, so each might have agreed always to reply to the other. This might have made up for the uncertainty about whether anyone would reply to a message – a way of combating the feeling of a 'cold medium'. If she found communicating through speech much easier than writing, she might have built on this by speaking aloud what she would say in a reply first, and only then put it in writing.

Perhaps you thought of other strategies that either or both students could have adopted. Undoubtedly the strategies that we can think of are unlikely to be as successful as those the students decide for themselves. This is because we cannot know the reasons behind what a student says, or their circumstances of study. You yourself are in the best position to decide what will make a positive difference for you, and what actions or strategies might enable you to make the most out of time spent studying. Whatever the answers, the starting point is to make time for reflection: to explore what you want to study and why, and how you will help yourself meet the challenges that you will find as you work towards your goals, whatever they are.

References

Cook, M. (1995) Student Workbook: Learning to learn University of Humberside.

Wegerif, R. (1995) Collaborative Learning on TLO'94, IET, Open University, Milton Keynes.

2 Learning to understand

Although we spend large amounts of our lives learning, intentionally and otherwise, it is quite unusual to spend any time thinking about what learning actually is. This section gives you an opportunity to do so, and to consider whether how we choose to learn is always appropriate for what we are trying to learn.

2.1 Different conceptions of learning

Spending time thinking about what learning is, how we define it and what it involves, is important for two reasons. First it reminds us of the diversity there is in what and how people learn, and this can help to enlarge the repertoire of approaches we use ourselves. Second, through appreciating the diverse requirements of different kinds of learning, we can review the effectiveness of the strategies we use ourselves to achieve specific outcomes.

The diversity of learning depends on what is being learned as well as by whom and in what circumstances. Theories of learning have developed from studies of particular kinds of learning, and they have strengths and weaknesses which follow from this. For example, learning how to recognise and to recall road signs requires a different method from one we would use to learn how to ride a bicycle, or to chair a committee effectively. These are all examples of learning which make different demands on the learner. Similarly, study of this course involves a range of activities, from studying rather factual, explanatory text to interacting with fellow students and judging your own work. You are unlikely to find any one approach to learning equally helpful in meeting the challenges of these different kinds of learning.

Activity 2

Before reading further, spend a few minutes putting a definition of learning into your own words by completing this sentence:

At the end of the section you can look back to your definition, and reflect on whether you would then wish to re-state it or to make any changes as a result of the thought you have given to what learning means and to what it might require. You can also compare it to the kinds of answer other students have given when asked the question: 'What does learning mean for you?' as given in Box 5.

Researchers of student learning have asked students this question because of the differences between students in how they go about study. It appears that students have very different ideas about what learning is and what is required for effective studying. Students have been interviewed at different stages in their studies, and a variety of conceptions about what learning means have been identified. By grouping related conceptions, five distinct categories can be identified, and these are numbered from 1 to 5 in Box 5 'Students say that learning is …'.

Box 5 Students say that learning is …

-

a quantitative increase of knowledge

-

memorising

-

the acquisition of facts and procedures for later use

-

the abstraction of meaning

-

an interpretative process for understanding reality

-

changing as a person

Subsequent research among Open University students (Beaty and Morgan, 1992) found a range of conceptions similar to those of items 1 to 5 in the box among a sample of students at different stages in their study of the Social Science Foundation course. However, the frequency with which OU students also commented on the personal impact of their studies led the researchers to add a sixth conception to the list of five, which was: 'changing as a person'.

Many OU students report that they feel differently about themselves as a result of OU study. They often comment on feeling more confident, or on changes in what they do or how they choose to spend their time. It is changes of this kind that are summarised in the conception that learning can mean 'changing as a person'.

If we now look at all six conceptions of learning, we can see some of the different ideas about learning that people bring with them when they think about studying. These differences are about two key dimensions in learning: the process through which it happens, and the outcomes to which it leads. The first three categories in the list tend to emphasise the outcomes of learning and define these as additions, whether of knowledge, facts or procedures. The process is referred to as memorising or acquiring. The fourth and fifth tend to emphasise process, and describe this variously as 'abstraction' or 'interpretation'. Whereas conception number 3 refers to practical application as the purpose, number 5 refers to 'understanding reality'. The sixth conception, 'changing as a person', again emphasises process but with the emphasis on the person being different, rather than having more knowledge or being able to do more things.

The different ideas about learning that we bring into our approach to study are often not something we discuss directly. We are much more likely to chat about what we find difficult or easy, our preferences for different subjects or for different components in the course materials. We can see fairly immediately that people differ in how they respond to the same teaching material, and we can relate that to the differences we know of between people's personalities and experience. What we may not be aware of is that learning itself is diverse, both in its outcomes and in the kind of activities that result in those outcomes. If we become aware of this diversity, we are more likely to be able to decide on the kinds of learning activities that best support the outcomes we aim for. Activity 3 'In what ways is learning diverse?' invites you to explore your own experience of different kinds of learning by applying the ideas of process and outcome to three contrasting examples.

Activity 3

In what ways is learning diverse?

Using a version of Table 4 in your learning file, note down a description of something you have learned in each cell of the first row – three examples in all. Try to choose three examples which differ from each other in important ways.

| First learning example | Second learning example | Third learning example | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Description of each example | |||

| What kind of process? | |||

| What outcome/results? |

Now, in each case ask yourself:

-

What kind of process did the learning involve?

-

What was the outcome for you personally?

Make a note for yourself in the relevant row in each column. To help you complete the table, some suggestions are set out below about what you might consider under the heading of 'process' and 'outcome'.

Process

When thinking about process, you need to remind yourself of the circumstances in which the learning came about and what the experience was like. For example, were you on a course of any kind or was the learning a byproduct of carrying out your job or some other role? Did you take the initiative or was someone else in control? Did the pattern of control change over time? Did you learn by a process of practice with feedback, by experiencing something and thinking through its meaning or implications, by trial and error, talking to people, self-instruction via books, software, audio and so on? Did the learning make life easier or harder at the time and why?

These are just some of the issues you could consider in thinking through what the learning process was like.

Outcomes

Outcomes can take the form of:

-

changes to what you know,

-

changes to what you can do,

-

changes to how you value ideas and experiences.

Ask yourself whether your learning led to knowing more about something. Or did it lead to a new ability to do something or an improvement in something you were doing already? Did you feel different as a person? Did it change your attitudes or your future choices in any way? You might like to post a message to the Comments section below containing some of your thoughts.

Now you have completed your own review of three contrasting examples, you can compare notes with the entries shown in Table 5, compiled from students' responses to a similar activity. Taken together with your own, what do these entries tell you about the differences between outcomes and processes of learning?

| First student | Second student | Third student | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Description | Losing control of a car and going off the road | Becoming a dance teacher/amateur actress | Identifying marine invertebrates |

| What kind of process? | Learned from experience. I had to analyse why I lost concentration, what I should have done. | Took up to meet people. Learned by example, watching more experienced. Gradual ability to perform grew over several years. | Needed for job. Trial and error process, a mix of asking colleagues and consulting the literature. |

| What outcome/results? | Fear of driving. Now much more cautious, permanently aware of dangers. | Increased confidence; better posture, voice control. Enjoy team work and entertaining others. | I am now the 'expert' for less experienced colleagues. Better concentration. |

These examples illustrate one aspect of the diversity of learning, which is that unintentional learning, where we learn from direct experience, can have some of the most powerful and long-standing effects on us. The learning we do is a reaction to the quality of the experience that we have, whether pleasant or otherwise. But it is also influenced by how much we reflect on that experience or try to influence what might happen in future. A minor car accident could lead one person never to drive again, whereas another decides to take the advanced driving test and build up better skills for handling cars in difficult conditions.

Some of the most important things we learn as adults are also the result of pursuing goals which require that we learn to do something new or to do something differently. The learning is not undertaken for its own sake, nor is it the primary goal; but it's undertaken for what it enables us to achieve. This is the kind of learning we do when carrying out a role at work or in our personal lives. In these circumstances, what and how much we learn can depend very much on how prepared we are to go into issues more deeply, or to take on jobs which require that we find out about new things or stretch our abilities in some way. Thus, some people are prepared to study and to set themselves intentional learning goals – because they want to do a particular job or to do it differently.

Where learning is intentional, the process can still be very varied. Such learning may or may not take place in association with formal education or training, and it can involve any combination of activities from a range that includes direct teaching, self-instruction, practical experience with feedback, trial and error, self-evaluation, consultation with experts, drill and practice, rehearsal, team working, role play, simulation, and so on. These differences in learning process result from:

-

choices or preferences of the learner,

-

the context in which learning takes place,

-

the nature of what it is that we are trying to learn.

The remainder of this section is about the last of these three things, and introduces a scheme for distinguishing between the differences in what we are trying to learn which have a direct bearing on how we should attempt to go about learning them.

2.2 Memorising, understanding and doing

You are now likely to be aware of various ways in which learning is diverse – as a process and in terms of its outcomes. In this final section is a very simple scheme for discriminating between the demands made on you, the learner, by different kinds of learning goals and the processes entailed in achieving those goals.

Theorists of learning have different ways of categorising the diversity of both outcome and process in learning. The scheme we are going to work with here uses three distinct kinds of learning: memorising, understanding and doing (Downs, 1993, 1995). This creates the memorable acronym 'MUD', and all three kinds of learning are required in this course. You can use MUD as a reminder to ask yourself whether you are studying in the most effective way for the achievement of the task in hand. The next three subsections provide brief discussions of each kind of learning.

2.2.1 Memorising

We sometimes have to remember words, names, symbols and other signs, simply because there is a convention that they will stand for some accepted meaning. This is the kind of learning we use, for example, when we memorise road signs, or the conversion of metric to imperial measures, or lists of words in a foreign language. However, very little of what you study in this course will require this kind of rote learning. You may need it if you try to remember certain definitions, for example. You will certainly need it at the beginning of learning how to use a software package if you have no prior experience of the package, because you will need to remember what to do in what order, and what certain symbols or actions mean. Unfortunately, we are not likely to understand complex ideas and experiences by applying the methods of rote learning, which typically involve repetition, silently or aloud, association with visual or auditory cues, and strategies such as mnemonics and rhyming.

Being able to remember things is important in all kinds of learning, however, even though the memorisation is not always the kind used in rote memorisation. We may be able to remember something, for example, because we can draw on our general understanding or knowledge to help us to recall that piece of information. I might be able to remember the name of a component or process, for example, because I understand something about the system of which it is a part. This is the kind of remembering, rather than rote learning, which is typical of the learning that is required in this course. Such remembering comes after the effort to understand something, or to construct some representation of principles or frameworks which make sense of detailed information. It is not that remembering is unimportant in academic study, but that it needs to follow from the effort to understand rather than from rote memorisation.

2.2.2 Understanding

Much more important than memorising, where academic study is concerned, is understanding. This is the kind of learning which requires a willingness by the learner to work with ideas and concepts, and a willingness to explore whether an idea has really been mastered or only partially grasped. Making mistakes can be a helpful stage in this kind of learning because the mistakes can reveal what it is that is not understood. It is when we put right, or sort out, such mistakes in understanding that we clarify our thinking and build a firm basis for later study.

The methods appropriate for this kind of learning typically require the learner to work actively with new information and ideas. This can be achieved by inviting learners to apply, or to elaborate, or to evaluate what they have been given. They can also be asked to create their own ideas and frameworks. The learner is active because he or she is applying ideas to different contexts, or checking out relationships in a variety of scenarios, or testing out generalisations against many different cases. Drawing graphical representations of how different ideas relate to each other is also a very productive way of checking out whether we understand, and exploring how firmly we have grasped something. Perhaps the most telling activity of all is to try to teach another what we have just learned.

'Teachback', where one learner spends a few minutes trying to teach another a theory or concept they both need to understand, can be an extremely effective way of sorting out the known from the unknown or the confused. All these activities 'give birth to learning' because they foster independent thought, self-checking and construction of links and relationships between the different areas of our own knowledge and thinking (Laurillard, 1993).

2.2.3 Doing

Finally, learning how to act or perform in particular ways is essential for the development of all kinds of intellectual and physical skills. For example, we need to be able to learn how to create a variety of kinds of written communication, or how to present complex information in a clear diagram, or to decide how a team will structure its work, and so on. No amount of explanation of how to compose a clear technical report, for example, would provide convincing proof that we could actually produce such a report ourselves. For that we would be expected to offer a practical example or demonstration. In some cases the skill really does need to be demonstrated, for it consists in how something is achieved as well as in the end result. Most of us have probably decorated a room to reasonable effect, but the expert decorator not only produces a good end result, but does so more quickly and with minimal waste. We can fully appreciate the expertise only if we watch the skill in action. Similarly, our skill as a team player could be best appreciated through observation of at least some elements of our interaction with the team in achieving its goal.

The learning we need in order to become proficient in a skill or a performance of some kind may well draw on both memorisation and understanding (as outlined above), but it will also require other activities. The learner needs experience of practising the skill under controlled conditions and with effective feedback which enables the development of improved performance and strengthened capability.

Take the skill of playing a musical instrument as an example. Most beginning learners are given mnemonics or chanting rhymes by which to remember the names of all the lines and spaces in the written conventions of the music they are to play, because they simply must know these (and other conventions) by heart. Their reaction to the printed page must be automatic recognition of the notes and symbols used, together with the appropriate physical response. A general understanding about musical conventions and how to look up the names of musical notation will not help to develop such performance skills. However, the fluency of physical response essential for a competent performance will require much more than memorisation. It requires extensive practice and rehearsal of graded examples of music, with detailed feedback from an expert and continual self-evaluation. As musicianship develops, understanding of style and musical genres will become important in helping the player to interpret what the composer intended and in creating the appropriate sounds and effects.

It may be that people underestimate the degree to which practice (rather than innate ability) is required for skill to develop in a whole range of abilities. Studies of musicians have certainly demonstrated that inherited ability plays a much smaller part in exceptional achievement in performance than many people suppose (Sloboda, 1993). Much more important than innate ability is the length of time spent in daily practice over many years, plus exposure to music. On the basis of studies of this kind, the value of practice with developmental feedback has been emphasised as the crucial activity for skill formation and improvement. This applies to the skills of both communication and learning which are included in the course learning outcomes for this course.

2.3 The learner's repertoire

Much of the learning required in this course is a mix of understanding and skill development. Very little rote memorisation is involved. In learning generally, the different kinds of activity required for memorising, understanding or doing, are more likely to be required in different combinations than singly, in isolation. In addition, activities can be useful for more than one kind of learning so it is important to see MUD as a working tool for developing practice, rather than as a rigid system that you must stick to.

In Box 6 'Learning activities' there is a summary list of activities organised according to the headings of memorising, understanding and doing. The lists are not a comprehensive record of everything that could possibly promote memorising, understanding or doing, but they are a starting point. Check down each of the lists in turn and note down your response to the questions below:

-

Which (if any) of these activities do I use much more often than others?

-

Are there activities listed which I should try to use more often?

-

Do I try out different activities if I find myself getting stuck or bogged down in some parts of the course?

Select one of the activities listed and try to use it more often during the next week or two of study. Return to the list every few weeks and check down the activities for those that you could use to good effect more often than you tend to do.

Box 6 Learning activities

Memorising

-

Using mnemonics.

-

Using cues involving visual and auditory memory – e.g. using written notes or a tape recording to help remember something in a lecture, using colour codes for notes, hearing yourself or someone else read something aloud.

-

Repetition of lists or other information in the same order – silently or aloud.

-

Self-testing at regular intervals.

-

Getting someone else to test you.

-

Setting things down in a succinct way that you can visualise, e.g. tables, drawings, mind maps such as spray diagrams, tree or root structures, etc.

-

Associating new information with something you already know well.

-

Chanting using a rhythm or rhyming pattern.

Understanding

-

Knowing why you want to learn something.

-

Setting yourself questions before, during and after study, for example.

What if …? questions

-

Checking questions, for which you should be able to find the answers in the text.

-

Comparison questions: Why is this topic important? How does it relate to other parts of the topic I am studying? What is it similar to, what is it different from?

-

Causation questions: What can go wrong? What causes what? What prevents or what leads to particular effects? And so on.

-

Imagination questions: How might it be different from a different perspective?

-

What might be the reactions of someone with views different from your own?

Review questions: What have I learned? What do I need to learn next?

-

Brainstorming, i.e. generating ideas (alone or with others) without criticising or rejecting items first. The checking and criticising of ideas happens after the stage of generating ideas.

-

Asking questions which check out what you know and what you don't know, and which don't just request information.

-

Putting the expert's explanation into your own words before you ask a question.

-

Talking about what something means with other people; bouncing ideas off other people.

-

Visualising something in the form of a diagram.

-

Teachback – trying to explain to someone else what you have just learned.

-

Listening to other opinions or explanations; repeating the other person's explanation/opinion before giving your own.

-

Distinguishing between general principles and specific examples, and reflecting on how an example illustrates a principle.

-

Learning from mistakes.

-

Setting aside time for reflection on experience and progress.

-

Being prepared to tolerate partial understanding or ambiguities/uncertainties for a while.

-

Working on a problem with a group rather than on your own.

-

Recording reactions and progress.

Doing

-

Asking an expert to demonstrate a skill or part of a skill and to answer your questions about it.

-

Trying out the skill or performance before getting instruction.

-

Trying out procedures in a 'dry run' where mistakes don't matter.

-

Getting feedback from an expert before 'bad habits' set in.

-

Getting regular feedback on performance so you can review progress.

2.4 Using a variety of methods for effective study

You may find it difficult at this stage to recognise what kind of activity would be most helpful for which parts of course study. In any case, people differ in what works best for them. The important point is to review the activities you are using for studying, particularly where you are setting yourself ambitious goals, or where you are finding things difficult. It might prove helpful to try out activities that you often avoid, or to ask other students how they study parts of the course that you find difficult. We often tend to persist in the same approach to study, assuming that the only way of overcoming difficulties is to spend more time studying. It may be that we can also make progress by a better match between how we are studying and the type of material and study goals which are our target. Our goal should surely be to find more effective ways of studying and not just to try to find more time for study.

In the next section, the theme of matching the process with the outcome of study will be continued through exploring different theories about how learning happens.

2.5 Back to your definition

Now you have worked through this section, reflect on your own version of what learning is, as you drafted it for your learning file at the start of this section. Did you give more emphasis to the outcomes of learning, or to the process? Or did you find a way of balancing the two? Try to revise your own wording to your own satisfaction.

Learning is …

Do remember that definitions of learning often reflect the kinds of learning that were most important to us at the time, or were in the forefront of our minds when we drew up our definition. A realistic goal is to give yourself a definition which works for a particular purpose, such as the tasks you will be working on for this course. My own version of a definition, for the limited purpose of providing a working definition for this course, is as follows:

Learning is an interactive process between people and their social and physical environment which results in changes to people's knowledge, attitudes and practices.

References

Beaty, E., and Morgan, A. (1992) 'Developing Skill in Learning', Open Learning, vol. 7 no. 3.

Downs, S. (1993) 'Developing learning skills in vocational learning' in Thorpe, M., Edwards, R., and Hanson, A. (eds) Culture and Processes of Adult Learning, London, Routledge.

Downs, S. (1995) Learning at Work: Effective Strategies for Making Learning Happen, London, Kogan Page.

Laurillard, D. (1993) Rethinking University Teaching: a Framework for the Effective Use of Educational Technology, London, Routledge.

Sloboda, J. (1993) 'What is Skill and How is it Acquired?' in Thorpe, M., Edwards, R., and Hanson, A. (eds) Culture and Processes of Adult Learning, London, Routledge.

3 Acquisitive learning

What happens when we learn? I shall explore three explanations, or models, of learning which attempt to answer this question. These three models have particular strengths and weaknesses. The point is not to choose between them, but to consider which one has the 'best fit' for different kinds of learning.

3.1 The acquisitive model of learning

The three models are introduced in turn, and each is followed by an activity that invites you to apply the model to your studies.

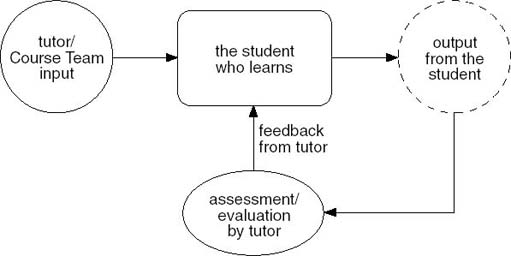

This model of learning starts from a focus on the observable behaviour of the learner and on the idea that this can be changed by feedback from the learning environment. It is associated with the idea that learning has to do with reproducing some desirable behaviours or measurable outcomes.

The learning process is seen as a process of accretion. Learners add to their store of knowledge those items that are required for them to achieve their current goal. Teaching, therefore, starts with the analysis of what is to be learned, so that it can be broken down into component parts which can be taught stage by stage. Each part is taught in a predetermined order and tested before the next part is learned so that the desired behaviour builds up incrementally.

It is essential to this process that learners have feedback regularly on how effectively they are achieving the desired learning outcome at each stage. If the learning is part of an education or training programme, the feedback is likely to result from some form of assessed performance and to include the response of a tutor. Feedback gives the learner information about how close they are to achieving the required outcomes so that they can modify and develop what they do in the required direction.

This approach to how learning happens has some similarities to an input/output model, with a feedback loop for correction of what has been recalled (see Figure 1). It also has some similarities with everyday thinking about learning, in that people commonly think of learning as knowing more: knowledge is a fixed object which one has more or less of, and learning is the process of acquiring more of it. The test of having learned is evidence that one can reproduce a near-exact replica of the knowledge or skill that was the objective of the exercise.

This approach to learning emphasises the desired outputs of the process but says little or nothing about what the learner should be doing or thinking while learning. The person doing the learning is simply a 'black box', taking in the information and generating the output, whatever that is.

The limitations of this model have frequently been recognised. Learning is not a passive process of absorption of an input, unmodified. It is an active process where the same input does not reliably produce the desired output. The same input and feedback will not produce good results with all earners, or even with the same learner all of the time. What goes on when we learn, and the influences that affect that process, have been left out in this model.

Also, for many things that we have to learn, successful learning cannot be adequately demonstrated in some form of behaviour. Much of what we must learn, for example, comprises not of details to be remembered, but ideas to be understood, and techniques for analysing and evaluating information. We also have to learn about attitudes, which may require us to change our perceptions, or to understand feelings different from our own. A simple input/output model will not take us very far with this kind of learning.

Nonetheless, in spite of its flaws, the acquisitive model is often implicit in the way we teach and learn. It has been used to produce effective learning opportunities for some purposes, and it can be modified in a number of ways to take into account the active role of the learner during learning. It can be modified, for example, to help the learner make a more coherent whole of topics learned in small, isolated chunks. In addition, some of the core ideas about breaking down what is to be learned into a paced programme of study, and providing regular feedback, have proved important for effective learning in a wide range of areas.

Activity 4 suggests that information which we simply need to know or to apply in problem-solving exercises might be learned by applying a modified acquisitive approach. Try out the activity to see whether this might suit the way you wish to study some parts of this course.

Activity 4

Memorising

There are units on OpenLearn that explain terms or concepts which may well be new to you and which would be useful for further study. Consider, for example, T551 Systems Thinking and Practice. The whole terminology used there of system, boundary and environment along with distinctions between systemic and systematic, reductionism and holism, interconnectedness and feedback is being used in a particular way, even if the words themselves are familiar. If this is new to you, you would need to find a way of familiarising yourself with some key terms and information. One way to do this is to select some key items from learning material and to re-organise them in two different ways:

-

in the form of a spray diagram

-

in the form of a set of questions on which you can test yourself or get someone else to test you.

Most of the hard work of sorting out what a system is and how it can be used as an aid to thinking has been done already, but reading through the learning material is not usually enough to enable us to remember the key points. One way of helping yourself to do this is to create a situation which gives you feedback on gaps in your knowledge.

Take the second suggestion listed above, which is to make up a set of questions from the material. Skim over the T551 course in question to get an idea of the course contents. If you studied this course, the list of questions might look something like this:

-

Name the three ways of thinking described.

-

How does positive feedback differ from negative feedback?

-

What is the full definition of a system of interest?

-

How can you distinguish between hard and soft complexity?

-

In what ways are levels and boundaries related?

When you've done some studying, you should try testing yourself to check out your memory of what could be considered basic information within the course. Better still, ask someone else to do so after a day or two, so that your immediate memory of the questions has faded.

If you do need to check up the answers, as you do so, you could draw a diagram or make further notes in your learning file to help you remember the key points.

You can use a similar approach to help you remember key points from the study of very large amounts of text. This is what we do when we reduce our notes to headings and try to memorise these in preparation for an exam. The headings are there to provide a reminder of all the details which we can then unpack in order to make arguments appropriate to the questions we have to answer.

Re-organising information, or reducing detail to summary lists and diagrams which we can reconstruct and check out through self testing with feedback, is useful for building up recognition and memory. It helps to create mental structures which support our need to review what we know and to use it flexibly, according to the immediate requirement. This kind of activity has been devalued because of its link with pre-examination cramming. But it can have a useful role for remembering both detailed information and summaries of key points. That is, it is a study skill to use at regular intervals.

3.2 The constructivist model of learning

This model of learning concentrates on what happens during the process of learning. It identifies the central role of concepts and understandings that learners bring to new learning and the way in which new and old ideas interact. Its starting point is that learners use their existing frameworks of understanding to interpret what is being taught, and that these existing ideas influence the speed and effectiveness with which new ideas are learned. Learners are actively involved in processing what is taught, and as a result, the same 'input' is perceived differently by different learners and may well have quite different outcomes.

This model of learning has been developed from studies of the kinds of learning required in higher education, and dissatisfaction with the acquisitive approach in this context. Its primary focus is on learning as a way of changing one's understanding, in particular coming to understand some aspect of an academic field of study (Ramsden, 1988). The learning process is seen as a product of the relationship between three interconnecting factors:

-

What students already know or can do.

-

What students think the subject they are studying is about and what it takes to learn it.

-

What teachers do, the tasks they set and the way these are interpreted by students.

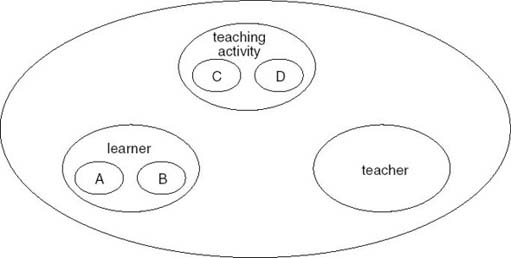

A system map can help clarify this approach to learning. Such maps are a way of showing the component parts which interact to create a system that is greater than the sum of its parts. Although the component parts may interact, it is not customary to indicate this by lines or arrows on this particular type of diagram. Thus although there are strong interactions between learners, teachers and the teaching content and media, these are not shown in the system map of a constructivist approach to learning in Figure 2.

Activity 5

Task 1

Looking at Figure 2, try to identify what the components within the 'learner' and 'teaching activity' subsystems labelled with capital letters A, B, C and D stand for.

Task 2

Note that the boundary round the three components or subsystems in the map separates them from the area outside, which is the environment. The environment contains items which influence the interactions within the boundary of the system. As you look at Figure 2, think about appropriate items that could be shown in the environment.

Discussion

My answers to Task 1 in Activity 5 are as follows.

The components in the 'learner' subsystem (labelled A and B in Figure 2) represent:

(A) the learner's existing knowledge, skills and attitudes

(B) the learner's ideas about how to learn the subject matter of the teaching.

The components in the 'teaching activity' subsystem (labelled C and D in Figure 2) represent:

(C) the content of what is taught

(D) the methods and media used to teach it.

Your components may have been different, while it would also have been possible to indicate components for the teacher subsystem, because teachers also differ according to their existing knowledge, ideas and practices, including their ideas about teaching and learning their subject.

Task 2 concerned whether you could identify influences from the environment. Two such components in the environment could be the institution in which the teaching/learning transaction takes place, and the Examination Board or Qualification Standards which govern the award of credit for learning. As both the Primer and Diagramming packs suggest, the purpose for which the map is created will determine whether components are placed inside or outside the boundary. For my purposes here, attention is focused on the interaction between who is learning, who is teaching and what the content and methods of the teaching are (including the media used). For this reason, I would place the institution and other elements in the environment outside the system, though they clearly do influence the interactions inside the system. You may want to have other elements in the environment of your system map.

For teaching which is based on a constructivist model of learning, the starting point is to help students integrate new learning with what they already know. This will very likely mean that existing ideas will have to change, sometimes extensively, especially if the new learning conflicts with existing assumptions and attitudes. The danger otherwise is that we do not realise the contradictions between old and new learning, and existing ways of thinking will tend to undermine new learning.

This also means that we need to be aware of how new learning affects what we already know and do. We need to engage in activities which really do foster the new understanding they are aiming for. Without this emphasis on understanding ideas for ourselves and in our own words, study can lead to patchy or superficial understanding. Overemphasis on memorising also tends to take attention away from the effort of understanding.

One of the ways in which understanding develops is by trying to work out the structure of what is being communicated, so that we can see what the relationship is between the different parts and make sense of the whole. As Laurillard has commented, 'The same information structured differently, has a different meaning' (Laurillard, 1993). We all know for example, the 'catch' drawings where we can see the same pattern of dots and lines two ways, depending on the structure we give it. Figure 3 is an example. It can be seen either as a young girl or an old woman, depending on which structure we impose on the information.

3.3 The experiential model of learning

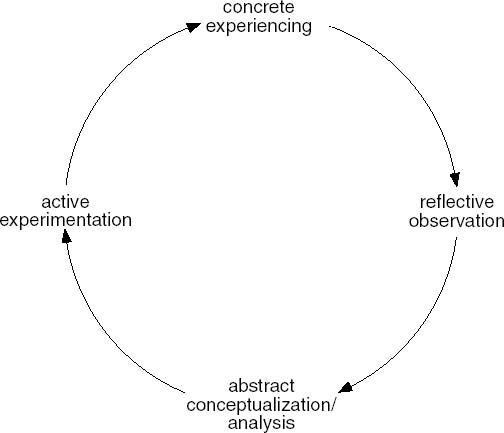

The main proponent of this approach to learning, David Kolb, put forward a theory which he intended to be sufficiently general to account for all forms of learning (Kolb, 1984). He argued that there are four distinctive kinds of knowledge and that each is associated with a distinctive kind of learning. The four kinds of learning are:

-

concrete experiencing

-

reflective observation

-

abstract analysis

-

active experimentation.

Kolb suggested that the ideal form of learning was one that integrated all four of these, integration being achieved by a cyclical progression through them in the way shown in Figure 4. The result of the journey round the cycle is the transformation of experience into knowledge, and this forms the basis of Kolb's definition of learning: the production of knowledge through the transformation of experience.