5.1 Paul Gauguin

When Gauguin went to Tahiti in 1891 to escape from urban modernity he took with him an eclectic collection of source material including Japanese erotica as well as illustrations of European ‘Old Master’ art – and including photographs of ancient Egyptian paintings from the tomb of the scribe Nebamun that he had seen in the British Museum on a visit to London in 1885.

He seems to have intuitively grasped that the ancient Egyptian artists were following conventions different from those of the European academic tradition, and to have occasionally ‘translated’ ancient motifs into his own system.

Gauguin’s paintings are complex, being on the one hand highly sophisticated and self-conscious examples of an avant-garde rejection of the conventions of bourgeois taste, and on the other seeking out ‘authentic’ effects according to the discourse of ‘primitivism’, which was beginning to be influential among artists tired of the superficial sophistication they saw around themselves in the cosmopolitan modern city.

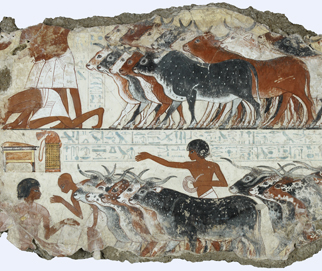

Christmas Night, (Figure 11) is a strange painting of an imaginary snowbound winter scene in Brittany, yet painted in Tahiti. It draws on the image of the cattle being presented to Nebamun for the annual roll-call of the produce of the estates (Figure 12). So too does a woodcut he made of another Breton scene, also done in Tahiti.

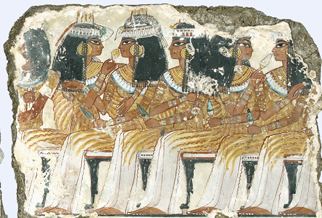

Another example of his use of Egyptian art is Ta Matete, also known as ‘We shall not go to the market today’. Here Gauguin drew on the banquet scene from Nebamun’s tomb-chapel (Figure 13). He depicted a row of five women sitting side by side in a frieze-like arrangement, some turning and talking to each other, some with hands raised in gestures, all except one in profile. The image is clearly based on the banquet scene from the tomb of Nebamun.

When asking ourselves what Gauguin was doing in these pictures, the first response might be to think along the lines of investing the scene with that element of ‘primitive authenticity’ we know Gauguin was keen to get into his paintings. But the complication here is that by this date Tahiti was far from an authentic Pacific paradise, and the women in the market painting are Tahitian prostitutes in western clothes waiting for the boats to come into the harbour. So in a strange, transposed sense, the painting is a representation of the ‘modernity’ Gauguin has sought to escape, refracted through this register of an ancient, erotically charged, banquet scene – which might well have appealed to him in the first place for that very reason.