2.1 Exploration

Now that you have looked in detail at the fragments of the banquet, what can you recover about the possible meaning of the whole?

Key point

When looking at paintings of any kind, it is often useful to keep two aspects in mind simultaneously: the subject matter that is being depicted, and the way it is being represented. Another way of putting this would be to say that we need to attend to both the form and the content.

When you consider the depicted subject matter, the thing you will find most noticeable, 3500 years later is the mixture of familiarity and unfamiliarity. It is quite difficult to assimilate different aspects of the scene into a coherent whole.

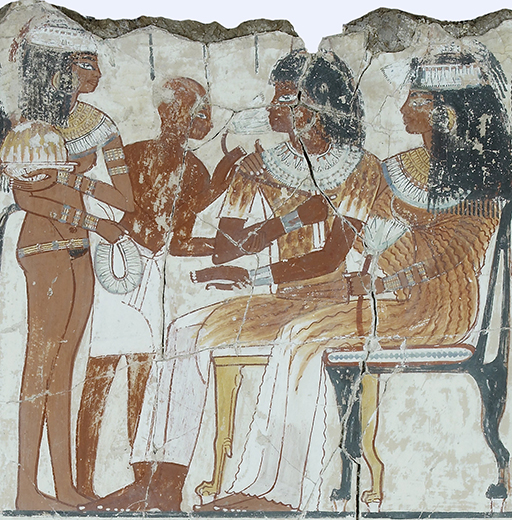

Twenty-first-century sociality in the West tends to be very informal. Egyptian society in the Eighteenth Dynasty, indeed at any time throughout its long history, would have been highly courtly, formal and hierarchical. We have mentioned nineteenth-century paintings of modern life, and it might help once again to think of the tightly structured society gathering one might find described in Proust, with seated guests, strict protocols about introductions and conversation, and a hyper-sensitivity to rank and decorum (Figure 8).

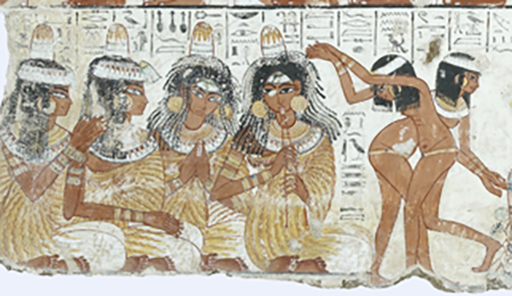

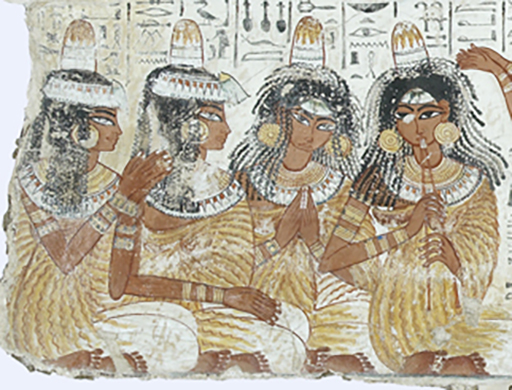

At the same time, of course, there is something quite different going on. In the Proustian soirée, the high society guests would have been sitting around on their chairs, being waited on, making polite conversation and sipping drinks. But the ladies and gentlemen would have been entertained by someone playing the piano or the violin, not by naked dancing girls hurling themselves around to rhythmic clapping and the rattle of a tambourine. It is hard to escape a stereotype of Orientalism here, if one gives the imagination rein to wander through perfumed air, drink in hand, to the sounds of ululating singers, a piercing flute and the strumming of the lutes. This certainly seems to have been part of the Victorian response – negatively attested to by the way the naked dancers and servants were obliterated from some photographs taken in the early 1870s (Figure 9).

Nebamun’s wake, if such this was, was far from Anglican. The mixture of music, conversation, eating and drinking, the smell of perfume and flowers adds up to something that is not what we would expect of a banquet devoted to the memory of someone who has just died. It all seems to have much more to do with life than with death. But that in its turn is probably more to do with our attitudes to life and death than with the way the ancient Egyptian ruling class conceived of that relationship.

When it comes to how the scene is represented, once again the question seems to require different responses.

In terms of the details, individual figures and groups of figures, the scenes are amazingly naturalistic, not least compared to the stasis we usually associate with Egyptian art. This effect is brought about partly by the relatively sketchy way the scenes are painted directly onto the plaster wall, sketchiness being something that, in the wake of Impressionism, we associate with values such as spontaneity (Figure 10).

This has not always been the case. To a classically trained Academician, sketchiness in a painting would have been a sign that it was improperly finished, perhaps even the result of incompetence. We have no way of knowing whether Nebamun’s tomb-paintings captured an intended effect or were dashed off quickly by workers eager to get the job done and get out. Or it may have been a technical constraint: the stone in the area was too poor to permit relief carving, so the paintings had to be made directly on the walls. The painterly skills are so vivid, however, that even if that was the case, perhaps the artists made a virtue out of necessity. Whatever the precise reason, it would be very hard for us not to see these paintings as miraculously accomplished, almost like snapshots that bring a remote culture powerfully back to life.

But for us this life likeness is then interrupted by the convention of the registers. What differentiates Egyptian painting, even these marvellously realised scenes of entertainment and leisure, is that the realistic detail of individual figures is not accompanied by an equally realistic spatial armature. There is no indication of where the musicians are placed, relative to the guests, whether the seats are in rows in front of or placed around the entertainment. We cannot even tell whether they are indoors or out.

The likelihood, given that this is not a royal palace, is that rooms would not have been big enough for so many guests, so the event is probably taking place in the central courtyard of a house, perhaps on a warm evening – though there is no representation of day or night for us to be able to tell. And yet, of course, this doesn’t seem to get in the way: we read a sense of the atmosphere from the figures and their actions and don’t feel the need to assess the plausibility of the setting.