A Europe of the Regions?

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 19 April 2024, 10:31 AM

A Europe of the Regions?

Introduction

This course discusses the future of Europe, and it looks particularly closely at what may happen to the smaller political units presently existing below the level of the nation-state. These include nation-regions like Scotland and Wales, larger entities like the German Länder, and smaller more recently created regions with less existing cultural unity. Despite the very large differences between them, for our purposes all these political entities are called ‘regions’. The course takes a historical glance at how they came into being, and assesses how they are being affected by political and economic developments like globalisation and the growth of the political institutions of the European Community. For the fate of the ‘regions’ depends not just on the nation-states of which they are a part: it cannot be separated from the future of the European Community (EC) itself.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of Level 1 study in Geography.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

recognise the varieties of region and sub-state nations that exist within Europe

explain the growth of regionalism

critically assess the view that what is evolving is a ‘Europe of the Regions’

engage better with debates about the future direction of Europe, and the place of your nation or ‘region’ within it

improve your skills of academic reading and note taking for future use.

1 Background and context to Europe's regions

1.1 The debates

How and why have Europe's regions and their relations with states been changing in recent decades? What roles are regions playing and likely to play in the emerging governance structures of the European Union (EU)? These structures, still in the process of formation, raise strongly contested normative as well as empirical questions, and regions occupy a central position in debates about past trends and possible futures. Three main political models have been proposed for the future of the EC, and each of course has to give an account of the regions. What is a model? Well, it is a simplified picture of more complex developments, showing their most important features. For instance, in debates about the EU's ‘democratic deficit’, is the answer a reassertion of liberal democracy in nation states, a return to a ‘Europe of Nations’ in the revealing misnomer of traditionalists opposed to regionalism and wedded to the so-called ‘nation state’? Alternatively, should democratic reconstruction involve a ‘Federal Europe’ super-state? Or does the future lie with sub-state identities in a decentralised ‘Europe of the Regions’? Which of the three models represents the most likely future? And which is the most desirable one? In the case of these political models, it is important to note that they are based partly on empirical accounts of what has happened, and partly on normative visions of what ought to happen in the future. For each has its own political supporters, and that means the debate is by no means simply academic! Away from the quiet of the ivory tower, politicians are arguing about the future of Europe. And there can be no doubt that what becomes of Europe will be determined in part by the models that the politicians have in their heads. All three models have been widely touted and all three reflect elements of reality; yet none on its own captures the complexities of a regionalising Europe. Instead, should we perhaps expect ‘more of the same’, with regions playing an increasingly important role in complex multi-level structures which continue to involve the nation states, the EU's central institutions, and other transnational political actors (see Bromley, 2001)? Perhaps in a sense the future has already arrived.

1.2 What does this course cover?

This unit offers some responses to these questions by outlining the variety of regions and regionalisms, their growth and its causes, their development in the EU context, and different future scenarios. Section 2 attempts to define ‘region’ and ‘regionalism’ in the face of their extreme cultural, economic and political diversity. Regions come in all shapes and sizes, some clearly demarcated by a long history, others little more than figments of a central bureaucrat's imagination. Regionalisms likewise range from an almost non-existent sense of regional identity to fully-fledged sub-state nationalisms, a form of identity politics which sees the ‘region’ as a potentially separate, independent country. The terms ‘region’ and ‘regionalism’ thus mask a range of quite different phenomena which vary not only from state to state but also within particular states, as is demonstrated very clearly in the cases of the UK (see Figure 1) and Spain.

Section 3 then sketches how regions in their various senses have increasingly become more important since the zenith of the centralised nation state in the Europe of the 1930s and 1940s. Regions have become more prominent in the economic, political and cultural life of virtually all European states (Harvie, 1994). There are a variety of reasons for this, including uneven economic development (and the lack of it), regional languages and cultures being threatened with terminal decline, and federalisation as a means of reducing the power of central states or, alternatively, a means of containing separatist aspirations and conflicts.

The increased salience of regions as units for economic, political and cultural development is not in doubt, but what is its overall significance? Despite the diversity of its expressions and causations, there are a number of unifying factors which give the regionalising of Europe some coherence. Particularly since the 1970s, sub-state regions in general have been subjected to many of the same pressures from accelerated globalisation. These pressures have both curtailed the independent economic power of supposedly sovereign nation states, and simultaneously put a greater premium on regional and local authorities presenting themselves as attractive locations for multinational investors. Regions have been forced or encouraged, as the jargon has it, to ‘think globally and act locally’, rather than simply relying on nation states to do their ‘thinking and acting’ for them, as was often the case formerly. This is especially true of regions in the EU where these developments have advanced furthest, and the EU now has an increasingly important regional dimension (Jeffery, 1997).

Section 4 considers the EU itself as a product of more globalised competition and one of the most advanced political, as distinct from simply economic, expressions of globalisation. Here the impacts of globalisation, and particularly the encouragement of regionalism, are experienced in more heightened form than in the other major economic blocs in North America and East Asia, or in countries which have remained outside these blocs. For Western Europe's regions, economic integration in the Single European Market (SEM) since the late 1980s has brought additional threats and opportunities which have indirectly fostered regionalism, and increasingly this extends beyond Western Europe as the EU enlarges eastwards. In straightforward political terms, the member states have lost some of their individual sovereign powers to the EU collective, and the EU provides an institutional ‘umbrella’ for regions, and for would-be states, as well as for the existing member states. In focusing on regionalism in the EU, Section 4 studies EU regional policies, regional networking and alliances.

This is the context within which rosy scenarios of a ‘Europe of the Regions’ were propagated in the 1990s. Traditional nation states were seen as generally too small for global competition but too big and remote for cultural identification and active, participatory citizenship. States were apparently being eroded from above by the EU and from below by regionalism – a pincer movement transforming traditional conceptions of the so-called ‘nation state’ and the national basis of territorial sovereignty and identity. Europe's future seemed to lie with a loose, decentralised federation of regions. Furthermore, while traditionalists defend their misnamed ‘Europe of Nations’ (that is, the existing nation states), the conflicts generated by the unachievable ideal of the homogeneous ‘nation state’ in places like Ireland or the Basque Country are a further argument for the emergence of a ‘Europe of the Regions’, or so the story goes. But, as we shall see in Section 5, there are good empirical and normative reasons for questioning the benign ideology of regionalism and its assumption that ‘small’ is necessarily ‘beautiful’. While global economic competition and the SEM may indeed lead to a more federalised and regionalised Europe, the EU's integration is still largely controlled by the existing member states and they continue to define the regions within their national territories. Besides, the strongest regional threats to nation states, far from being opposed in principle to the nation state ideal, are themselves nationalist in inspiration: they come from ‘nations without states’ (Guibernau, 1999) where nationalist movements (in, for example, Scotland, Wales or Catalonia) reflect and foster strong cultural and political identities, and typically the ultimate (if not immediate or practical) objective is their own ‘nation state’. However, such nationally inspired or ‘national’ regionalisms are the exception in Europe's regions, and indeed the great diversity of regions constitutes a major reason why they are unlikely to become the basis for a ‘new Europe’.

On the other hand, reversing the rise of regionalism and returning to a traditional ‘Europe of Nations’, as advocated by an extreme nationalistic faction in the British Conservative Party since the 1980s, seems at least equally unlikely. Yet a fully federal European super-state, whatever its advantages in terms of democratic transparency and formal representation at different territorial levels, is also implausible – the process of federalisation is likely to be arrested long before giving birth to a ‘United States of Europe’ on the North American model. Section 6 considers different future scenarios and stresses that the future, like the present, will probably be more complex than any of these models suggests. But if a ‘Europe of the Regions’ is ruled out, how will increasingly important regionalisms relate to other ‘possible Europes’ – of cities, cultures, nations, states and transnational institutions? Rather than neatly displacing nation states or other forms of political and cultural identity, it seems more likely that enhanced regionalisms will have to coexist with them.

The regional question in Western Europe is thus inextricably bound up with wider empirical and normative debates about nation states and the EU, and issues of culture, politics, development, identity and democracy (Newman, 1996).

2 The diversity of regions and regionalisms

2.1 What do we mean by ‘region’ and ‘regionalism’?

‘Region’ here refers to any piece of continuous territory, bigger than a mere locality or neighbourhood, which is part of the territory of a larger state (or states), and whose political authority or government, if it has any specific to itself, is subordinate to that of the state(s). Conventionally, most such ‘sub-state’ regions, and particularly most regions defined in terms of political authority, have fallen wholly within the borders of a single state. However, in situations where those borders are contested, as for instance in national separatist or irridentist conflicts, the relevant regions may straddle state borders; and in contemporary conditions of globalisation and transnational integration, as in the EU, cross-border regions can play a special integrative role. The related term ‘regionalism’ has perhaps even more varied meanings. It can refer to the top-down imposition (or ‘regionalisation’) of administration or government based on regional territory; or it may denote an active bottom-up identification with the region in social, cultural or political terms, a regionalist movement seeking more autonomy for a region, or a regionally-based nationalist movement which seeks a separate state; or indeed it may refer to any combination of these.

2.2 Diversity between states

To attempt more precise definitions would run the risk of arbitrarily excluding many of the phenomena we need to address. In fact the intentionally loose, multifaceted nature of these definitions reflects the reality of regional diversity, which has many dimensions. The differences start with the states which in practical political terms largely define regions, for they are themselves very different in area and population size, in economic strength, in cultural homogeneity or heterogeneity, and in political structure. A diversity of state forms – unitary (for example, France, Portugal, Republic of Ireland), federal (Germany, Austria, Belgium), and ‘quasi-federal’ or with non-uniform limited regional autonomy (Spain, Italy, the UK) – produces a diversity of regions. In a fully federal state (for example, Germany), governmental activities are divided between the centre and the regional units (for example, Lander) so that each level has the right to make final decisions in some fields of activity. There is a wide spectrum between this and the extremes of authoritarian centralism (for example, in Spain under Franco's dictatorship). Likewise, there are many gradations on the identity spectrum, from full national separatism based on a distinct culture and language to, at the other extreme, the absence of any popular identification with a purely administrative division that lacks any historical basis or cultural significance.

Thus Europe's regions display huge variations not only in their economic development, but also in their degrees of political organisation and autonomy (if any), their status with respect to central state institutions, their historical basis or lack of it, their cultural distinctiveness, and so forth. Germany's federal region of North Rhine Westphalia with some 15 million people is over three times bigger than a member state such as the Irish Republic, while the latter's centralism has generally precluded effective regionalism (see Section 2.3 below). Some regions are administrative concoctions with little or no popular identity, and while some of the strongest are ‘national’ regions comprising historic nations (for example, Scotland and Catalonia which once had separate statehood), other strong regions, such as Baden-Wurttemberg and Lombardy, are not based on a national history or any very marked cultural distinctiveness.

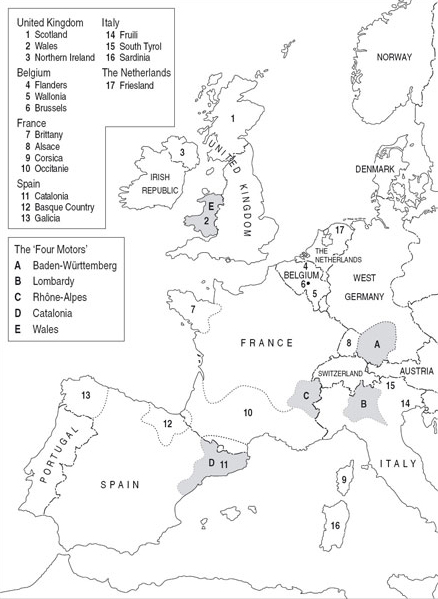

There may, though, be some convergence between the ‘national’ regions and the stronger ‘non-national’ ones: the former may experience a ‘regionalising’ of sub-state nationalisms (settling for autonomy rather than full independence within the EU framework), while the latter may undergo a ‘(quasi) nationalising’ with further development of their autonomist identities and growing distinctiveness. Baden-Wurttemberg and Lombardy with Rhône-Alpes, Wales and Catalonia (see Figure 2) together formed the ‘Four Motors’ cross-border alliance of regions, all city-focused and examples of what Harvie (1994) calls economically successful ‘bourgeois regionalism’. (Wales was not one of the original four members, but has now joined these.) We shall come back to the ‘Four Motors’ as an example of regional networking in Section 3.2. In contrast, other regionalisms mobilise support around the problems of economic or cultural decline. Furthermore, many regions, whatever their problems, also have the problem of lacking a basis for regional mobilisation – they may have little or no cultural identity, or a weak and fractured geographical structure, or they may be riven politically by local rivalries and internal divisions between competing local authorities.

Distinctions must be drawn between, on the one hand, the bottom-up development or resurgence of sub-state nationalist and populist movements, often based on the identity politics of long-established regional cultures and languages which often pre-date the state, and, on the other hand, the top-down imposition of administrative or economic regionalisation, or the designation of ‘problem regions’ and ‘regional problems’ by central state bureaucracies. However, as in the Napoleonic system of regions administered by centrally-appointed ‘prefects’, top-down regionalism can be long established, and in some cases imposed regions can later become the basis for popular ‘bottom-up’ regionalism.

2.3 Diversity within states

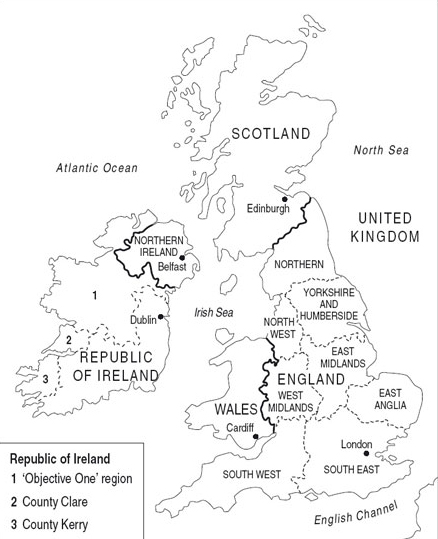

There is no simple or necessary correspondence between types of region and types of regionalism. But clearly-demarcated and long-established regions are a more likely basis for strong regionalist or nationalist movements, while top-down regionalisation often results in regions with little popular identity or awareness of the region by its own inhabitants. Pre-existing regional diversity provides an uneven basis for regionalising a whole state. For example, regionalising the UK is relatively easy in the case of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, but extremely problematical for English regions (see Figure 1).

(adapted from Butt Philip, 1999; Government of Ireland, 2000)

This is perhaps especially so in the central ‘Midlands’ area where there are no clear boundaries. But even in the relatively strong Northern Region there are problems: the ‘Campaign for a Northern Assembly’ was transmuted into a ‘Campaign for a North-East Assembly’ which now covers only the eastern half of the region, much to the annoyance of remaining campaigners to the west. Similarly, in recently regionalised Spain, there are ‘strong’ pieces in the jigsaw, such as the ‘national’ regions of Catalonia, the Basque Country and Galicia, with their own specific cultures and languages and memories of a time when they were independent or had autonomous political institutions and laws; but there are also small newly created regions such as Murcia and tiny La Rioja which filled awkward gaps between more established regions.

2.4 Summary

‘Regions’ and ‘regionalism’ in Western Europe display great diversity in economic, social, cultural and political terms, varying not only between states but also within particular states (as exemplified by the UK and Spain).

Regions vary widely in their size, population, levels of economic development, historical origins, contemporary identity, cultural distinctiveness and political activism (or in some cases the lack of distinctiveness and activism).

Activity 1

To illustrate the diversity of regions in Europe, note examples of each of the following:

a region that is bigger in population than some EU member states;

a region that could lay claim to being a historic nation;

a city-focused region;

a region which could be said to fill ‘an awkward gap’ between more established regions.

3 The growth of regionalism and its causes

3.1 Introduction

Regionalism has grown remarkably since the high point of state centralism in the Second World War period. A succession of factors have come into play – uneven economic development, threats to regional cultures and languages, the decentralisation of some states, and more recently the impact of globalisation and European integration. The effects have been cumulative, with old factors continuing to operate while new ones were added, including, as we shall see in Section 5, the ideology that ‘small’ regions must be good in themselves and better than ‘big’ states or larger entities.

3.2 Growth of Europe's regions

In the 1960s and 1970s some states, including the UK, contributed to politicising regional economic development by first defining ‘problem regions’ (for example, Central Scotland) and then failing to solve their problems. Here central states were still setting the agenda, but increasingly the lead was taken within the regions themselves, especially in regions with past experience of autonomy or their own nationalist tradition.

Nationalism had a ‘bad press’ from the 1930s and 1940s, thanks partly to the extreme nationalism of Nazi Germany, and this was a low point for national separatist movements in Britain and elsewhere in Europe, though in Spain regionalism was directly weakened by Franco's repressive centralism. In contrast, by the 1960s there were autonomist and separatist movements active in varying degrees across Western Europe, from Ireland, Scotland and Wales in the north-west, through Brittany, Flanders and Wallonia, to the Basque Country, Catalonia, Corsica and parts of Italy (Figure 2).

(adapted from Anderson, 1995, p.91; Bull, 1999, p.142; del Río, 1999, p.168; Stammen, 1999, p.100; Wagstaff, 1999a, p.52)

Note: The ‘Four Motors’ are the four main high-tech regions that came together in 1989. They were subsequently joined by Wales.

3.3 Reasons for – and effects of – nationalisms and federalisation

Most of these regions had their own distinctive history and culture, often including their own ‘minority’ languages. However, there were contemporary reasons for the nationalist or regionalist resurgence, including economic and cultural problems and changes in the power and authority of central state administrations. In some cases (for example, in Ireland and the Basque Country) inspiration was derived from the example of anti-colonial liberation struggles and newly independent (often small) states in the ‘Third World’. In general, Europe's resurgent ‘regional’ nationalisms tended to be toward the left of the political spectrum (sometimes in contrast to antecedents in the 1930s, as in the Breton case), though, like all nationalisms, they encompassed a variety of views, and a small minority (for example, Flemish nationalism) was dominated by the extreme right and fascism.

The other major cleavages were between ‘constitutional’ nationalists who used only peaceful means of opposing the status quo and those who took up arms against the state, and (an often related cleavage) between those prepared to accept limited regional autonomy and those holding out for complete separation and a new state. Armed conflicts erupted in several regions, most seriously in Northern Ireland and the Basque Country, and the ensuing state repression generally fuelled the conflict rather than solved it. However, in no case did a nationalist movement succeed in its separatist aims. On the other hand, whether through peaceful means, armed struggle, or an uneasy cooperation/competition between the two, most of the regional nationalisms have achieved a greater degree of regional autonomy.

In some previously ‘unitary’ states (as in Spain) they also helped bring about a more general, though often partial or ‘arrested’, process of federalisation or devolution. Where states had only one parliament or representative assembly, and no political institutions representing distinct regions or cultural minorities, devolving or decentralising some political powers to regional assemblies in a more federal state structure was a means of containing separatist conflict. It might ‘buy off’ or deflect tendencies which threatened the territorial integrity of the entire state. This was the case not only in Spain but also in bilingual Belgium with its divergent Flemish and Walloon aspirations. To prevent the Belgian state disintegrating, there has been a continuing process of constitutional reform since the 1970s, resulting in a very high degree of autonomy for the two main regions, and also for Brussels which is inside the Flemish-speaking area but has been dominated by a francophone elite. This containment strategy can work – it has worked so far in Belgium. Out-and-out separatists may reject it as a ‘sop’, but they may become politically isolated if others accept that ‘half a loaf is better than no bread’. Autonomists are placated while more ‘moderate’ separatists can present federalisation as a relative gain and a ‘stepping stone’ or stage on a road which promises full independence. This, however, is an argument which also tends to be accepted by centralists who identify strongly with state nationalism (for example, British in the UK, Spanish in Spain), except that they see federalisation not as a promise but as a threat to ‘their’ state. They therefore generally oppose anything but the most minimal forms of centrally-controlled administrative devolution, and where more substantial types of devolution or federalisation exist they may act to curtail or remove them. But – in a further twist to the argument – this can be counter-productive, stimulating resentment in the regions and encouraging the very tendencies it is supposed to destroy.

There is thus a continuing dialectic between centralism and federalisation or devolution. The various arguments about their likely effects not only separate the pro- and anti-regionalist forces, they also divide each ‘camp’ internally, leading to political situations of great complexity. In consequence, the historical trends are by no means all ‘one-way’ – as was seen for instance in Britain where the very centralist Conservative governments of Mrs Thatcher reversed the previous trend toward regionalism. However, like Franco's centralism in very different circumstances, her centralist policies were to prove spectacularly counter-productive in their own terms in some of the key regions. She provoked Scottish nationalist opposition and growth, and the decimation of the Conservative Party in Scotland, and to a lesser extent in Wales. And by what was seen as her callous treatment of dying IRA hunger-striking prisoners protesting against her attempted ‘criminalisation’ of them, she inadvertently launched Sinn Fein as a successful electoral machine in Northern Ireland.

3.4 The trend towards increased regionalism

However, despite the complexities and reversals – mostly temporary – the dominant trend since the 1960s has undoubtedly been toward increased regionalism. Prior to 1970, the Federal Republic of Germany was the only major west European country with elected governments at a level between local municipalities and the central state (with the exception of Northern Ireland, an ‘exception which proved the rule’ for the UK); and even in Germany there had been some centralisation of power, and federalism was weak and getting weaker (Newman, 1996). Unitary states with varying degrees of centrally-controlled regional administration then dominated the scene. But that is no longer the case, thanks in part to separatist pressures, but also to processes of democratisation, globalisation and European integration.

Germany's federal Länder were originally established as a means of reducing the power of the post-war German state, countering authoritarian centralism and rekindling democracy. Similarly motivated concerns to dismantle fascist or semi-fascist legacies of over-centralisation were involved in the decentralisation in Spain (and to a lesser extent Portugal) in the 1970s and 1980s, with Italy having led the way by excising some of its authoritarian legacy in 1970. It created fifteen regions, implementing regional devolution which had been envisaged in its 1945 constitution but not carried out. In these countries the process of setting up elected regional authorities reflected a general concern to revive democratic participation, as well as absorbing centripetal pressures and preventing geographical fragmentation, and their constitutions have now granted substantial autonomy to island regions and ‘historic nations’.

In different contexts, Holland and Denmark have created provincial assemblies, and even in France, the epitome of Jacobin centralism, a leftish government introduced a major decentralisation programme, setting up twenty-two regions and establishing regionally elected councils. True to its Jacobinism, however, France allowed these councils only limited autonomy within a fairly uniform and centralist all-France political structure; and it continued, for example, to refuse to recognise a distinctive ‘Corsican people’. The statutes of Corsica's regional government allowed the expression of sub-state identity only in so far as it conformed to the state's definition of the French ‘nation’ (Anderson and Goodman, 1995). An opportunity to reverse this trend was defeated in 2003, when the island's electorate rejected limited proposals for autonomy by 51% to 49%. As a consequence, France remains a highly centralised unitary state. Although the implementation of plans for decentralising was often slow (particularly in Portugal and Greece), and some of the regional bodies have quite limited powers (for instance in France), elected regional bodies have now established themselves as a permanent feature of political life in several of the smaller EU states and in the five largest ones, most recently in Britain.

3.5 Globalisation

All this was taking place in the global context of the ending of the ‘long post-war boom’ in the early 1970s. Profit rates were falling and there was a return of generalised capitalist crises, an intensification of competition and a consequent acceleration in the ‘internationalisation’ of production, as larger firms ‘went global’ in their search for restored profit levels. These developments not only exacerbated the problems of ‘problem regions’, they also led to fundamental changes in the relationships between regional, national and international economic processes.

This complex of factors, commonly referred to as ‘globalisation’, was accompanied by a revival of laissez-faire arguments against ‘state interference’, and a world-wide ‘privatisation’ of state-owned enterprises. State ownership and corporatist links between the state and ‘national’ capital generally became weaker and gave way to looser links with capitals of whatever ‘national’ origin or ownership that were located, or might potentially be located, within the state territory.

Globalisation, and particularly its economic aspect (though this cannot be divorced from the political), is perhaps the main or most general and basic factor behind the recent growth of regionalism. Economic development is the policy area where states are assumed to have lost much of their former independent powers and their control over their own ‘national economy’. It is also the area which provides the most widespread focus for the growth of regional and local politics as regions and localities strive to attract investment capital from external sources. Attracting external capital – ‘global’ in that it can in principle come from anywhere (and also might go anywhere else) – has become the touchstone of economic ‘success’ in more globalised markets. The social and institutional ‘support systems’ of local and regional economies and societies have been increasingly seen as crucial in the competition for attracting and retaining inward investment. Regional and local governments, and other regionally-based political and economic forces, became direct actors in transnational arenas, sometimes in association with central state institutions but now often bypassing them.

Particular regions became ‘success stories’ (for example, Emilia Romagna in Italy, which in per capita GDP went from forty-fifth to tenth richest region in the EU between 1970 and 1991). There were various attempts to explain ‘success’ in terms of a region's own attributes:

regions having their own elected government which could pursue regional as distinct from ‘national’ priorities;

a well-developed set of regional institutions and partnerships between the regional authorities and the private sector;

a good physical infrastructure in the region and a social infrastructure providing training and a skilled, reliable workforce;

regional specialisation, including for niche markets, and inter-firm linkages and sourcing which maximised the ‘value added’ within the region.

These various factors were given different weightings in different theories, but there developed a general consensus that economic success depended on regional governance and the ‘embedding’ of regional economies in a dense, supportive network of institutions (Simonetti, 2001). It was generally assumed or asserted that the region was indeed the best spatial scale for organising these prerequisites.

This orthodoxy or ‘new regionalism’ (Amin, 1999) has however been questioned by various sceptics. John Lovering points out for instance (Lovering, 1999) that it:

tends to systematically underestimate the continuing economic importance of the state (even in federalised states);

overestimates the coherence of most regions as a basis for development compared to the smaller scale of city or municipality;

is theoretically weak and based on relatively few, and in many ways exceptional, examples;

perhaps not surprisingly, has generally failed in practice to replicate ‘success’ in lagging regions.

Rather than being a theoretically grounded and empirically justified position, it is more an article of faith which in at least some cases is connected with a neo-liberal downplaying of nation states or concedes too much ground to this dominant ideology. It has interesting echoes in ‘Europe of the Regions’ ideology, as we shall see (Section 5).

Nevertheless, whatever the empirical and theoretical arguments against the ‘new regionalism’, regional authorities are under continuing pressure to appear attractive to investors and can hardly risk dismissing these ideas. They may be largely ideological but their sheer fashionableness gives them a material reality. Regions and regional governance are now an established part of political and economic life in Western Europe, and not least because of the EU.

3.6 Summary

Since the heyday of the centralised nation state in the 1930s and 1940s, most of Europe's regions have grown increasingly more important in economic, political and/or cultural terms.

This growth has been largely in response to regional inequalities in economic development, threats to traditional regional cultures, and the political federalisation of states, whether to reduce their centralised power or to contain regional separatisms.

More generally, since the 1970s, accelerated globalisation has meant that attracting external sources of investment has become more crucial and this has made ‘global’ or at least ‘international’ players of regional (and local) authorities, which now deal directly with the external sources whereas previously they had usually acted through their central governments or simply relied on the central authorities acting on their behalf.

Activity 2

Note examples of the following:

a nationalist/regionalist resurgence inspired by an anti-colonial liberation struggle;

a nationalism of the extreme ‘right’;

a region being granted autonomy in an effort to prevent state disintegration;

a region established as a way of reducing central power;

a region that has successfully attracted foreign investment.

4 Regionalism in the EU

4.1 Introduction

Since the ending of the long post-war boom in the early 1970s, the EU has developed in response to intensified competition in global markets, the member states have been progressively ‘pooling’ their sovereignty in economic matters, and globalisation's political consequences have gone furthest in the EU, not least in its regions. There are thus additional, specifically EU, factors in the growth of regionalism. It has been encouraged directly by the EU's regional policies and the regional engagements of its central institutions, particularly the Commission, the Parliament and the Committee for the Regions. There is the often explicit intention of advancing the EU's own cohesion and integration via the regions, and regions are seen as a distinct ‘third level’ of the EU along with its central institutions and the member states (Jeffery, 1997). Less obviously but very importantly, the EU has also stimulated regionalism indirectly through forces within the regions themselves responding to general integrative developments such as the Single European Market (SEM) and Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) (Anderson and Goodman, 1995). Regions striving to become attractive actors on the international stage find ‘Brussels’ a helpful prop (and literally a good place to set up a ‘shop-window’ lobbying office); and those seeking greater autonomy or separate statehood find the EU a useful ‘umbrella’ in providing a trump card against arguments that they are too small and parochial. They can have ‘independence in Europe’, in the slogan of the Scottish National Party, with the obvious corollary that it is in fact the British nationalists defending the integrity of the UK state who are being ‘parochial’. Thus while the diversity of regionalism is qualified by the common factor of globalisation, the EU gives it a further overarching ‘unity’.

4.2 EU regional policies

Initially, from 1957 to the mid-1970s, the European Community, in line with the dominant centralism of its member states, showed little interest in regional problems, with the exception of south-west France and the chronic ‘underdevelopment’ of southern Italy. Generalised regional policy only developed from 1973 when the UK and the Irish Republic joined, though ironically they have been among the most centralist of all member states. However, they wanted ‘compensation’ for their regional problems and their relative poverty and peripheral location with respect to continental markets, and these were major issues in the negotiations to join. In consequence, the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) was set up in 1975, and regions in the north and west of Britain, all of Ireland, and north-west France were added to the recipients of regional aid.

However, it was only in the face of accelerated globalisation, and particularly the intensified competition from the world's two other main economic blocs based on the USA and Japan, that economic and social ‘cohesion’ became a major EU objective. The Single European Act was passed in 1986 to establish the SEM by 1992; and it favoured cross-sectoral development strategies at regional levels and ‘fine-grained’ region-to-region, rather than simply state-to-state, integration. In 1988 the structural funds (the ERDF, the Social Fund and the ‘guidance section’ of the Common Agricultural Policy) were doubled, and there was a decision to concentrate resources in regions ‘lagging behind’ – the so-called ‘Objective One’ regions. Altogether five regional ‘Objectives’ were created and these subsequently became a focus for alliances, as regions of the various types, especially those with ‘industrial’ and ‘rural’ problems, sought to defend their particular interests. Though it was mainly the state governments that did the negotiating, the EU insisted that they consult their regional ‘partners’. The ‘region-forming’ role of the Commission was clearly seen when it forced the Irish government to re-establish regional advisory bodies in 1988, one year after the government had dissolved them in a budget cut (Anderson and Goodman, 1995)! A decade later when the economic success of the ‘Celtic Tiger’ meant that the Republic of Ireland as a whole would lose its ‘Objective One’ status, the government redrew the regional map dividing the state into two regions in order to retain this status for the relatively poor counties to the north and west. But then for short-term reasons of electoral expediency, it included Counties Clare and Kerry (see Figure 1 in Section 2.3) which did not qualify for ‘Objective One’ status on the standard per-capita income grounds, and again the Commission stepped in, excluded these counties and determined a regional framework.

In 1988 the Commission created the Consultative Committee of Local and Regional Authorities to strengthen its own links with these sub-state bodies. The Commission's periodic ranking of regions for aid purposes also increased the political significance of regions, and the legitimacy of regionalism was further enhanced by the Regional Policy Committee of the European Parliament which sponsored two ‘Regions of the Community’ conferences in 1984 and 1991 (the 1984 conference leading to the creation of the Association of European Regions with over 170 members). The Commission also sponsored the Association of European Border Regions and in 1990 established INTERREG, which involved pooling the various structural funds available to the respective border regions in order to promote specifically cross-border economic cooperation. As well as directly furthering economic and social ‘cohesion’, regionalism has also been encouraged for the more political if less acknowledged objective of countering or bypassing state governments where they presented obstacles to integration. Regions and regionalism were allies or potential allies for the Commission vis-à-vis inter-governmentalism and the controlling states.

The Commission's 1991 regional discussion document Europe 2000 (an early example of the ‘new regionalism’, above, which drew on optimistic versions of ‘post-Fordism’) argued that with ‘flexible specialisation’ reducing the importance of scale economies, less advantaged regions could become prosperous by producing specialised products for niche markets. It argued that ‘flexible production systems’ were making firms more mobile and that their location decisions were increasingly influenced by qualitative life-style factors. Drawing on the experiences of ‘Silicon Glen’ in Scotland, Rennes in France, the Basque Country in Spain, and South Wales, and noting the potential of information technology and telecommunications for altering comparative advantage, it claimed that ‘new location factors’ were opening up economic opportunities for peripheral regions and more ‘even’ development. However, it remained the case that EU integration was mainly a market-led neo-liberal project and the redistributive measures to counter the negative effects of integration were (and still are) very limited. EU regional funds, for instance, typically amount to less than 1 per cent of total EU GDP (and less than the efficiency gains from the single market which largely accrue to the already better-off regions), though regional aid has increased and the structural funds have amounted to well over a third of the EU budget compared to less than a tenth in 1980.

4.3 Regional networking and alliances

Increasingly, regions have become important players in their own right. Partly because of encouragement and legitimation from EU institutions, but also on their own initiative and in response to the threats and opportunities of the SEM, regional interests have been demanding more powers and resources. In many cases regional authorities have played a key, neo-corporatist role in stimulating economic development, linking ‘Eurocrats’, multinational companies, the local bourgeoisie, politicians and trade unions, and educational and training establishments. The lack or weakness of regional political structures is increasingly seen as having a debilitating effect on regional economic performance. This ‘new regionalist’ argument (see Section 3) is widely used by regional groups seeking more autonomy or self-government.

To further these political objectives, regions have increasingly become involved in creating transnational alliances with other regions, new cross-border regional entities, and the Committee of the Regions. There was an upsurge of transnational inter-regional cooperation manifested in a multiplicity of regional groupings and associations reaching across the member states. Thus the ‘Four Motors’ – the ‘bourgeois regionalism’ or ‘high-tech’ association of Baden-Wurttemburg, Lombardy, Rhone-Alpes, Catalonia, and, more recently, Wales – was established in 1989 with encouragement from the EU (see Figure 2 in Section 3.2). It was explicitly presented as an alliance which would enable these strong regions to take a ‘pathbreaking role’ in the new Europe (Harvie, 1994), while for Catalonia it was also a means of asserting its own separate national identity and pursuing its own ‘European’ interests rather than making common cause with poorer regions in Spain. However, while some of these alliances continue to reflect substantial economic and political linkages, many had little substance or were arbitrary and lacked identity or legitimacy (for example, the ‘Atlantic Arc’ linking Wales, Brittany, Aquitaine, Galicia). The diversity of regions, particularly across different states, militates against the formation of coherent regional alliances and only rarely do they link the interests of ‘core’ and ‘periphery’ or rich and poor regions. In general the new cross-border regions formed by contiguous regions from either side of a border (for example, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland) are on firmer footing, though such entities often suffer from having a history of antagonism (for example, Kent and Nord Pas de Calais) rather than a history of cooperation on which to build.

4.4 The Committee of the Regions

The regions, however, have a privileged place in EU integration, and the Committee of the Regions has the status of an ‘expert’ which must be consulted on issues of cross-border cooperation. This Committee epitomises both the growth of EU regionalism and the obstacles it faces from diversity and from conflicts of interest with state governments. Strong regions, particularly German Länder, played a key role in establishing this ‘advisory committee of representatives of regional and local authorities’. In reasserting their eroded constitutional rights from the late 1980s, the Länder opposed the practice of the federal German government – and by extension other central administrations – of deciding how regional EU aid is distributed, and they called for some regional representation at the Council of Ministers, the EU key decision-making body. The Länder, the EU Commission and the European Parliament favoured the Committee of the Regions having real decision-making powers and a membership of elected regional and local politicians with democratic legitimacy. But state governments, including the German government, were less enthusiastic, and the highly centralist British and Greek representatives were openly hostile, proposing to send along unelected civil servants answerable only to central government. The then Conservative British government wanted to avoid empowering regions in the UK, seeing regionalism as a ‘slippery slope’ to the break-up of the UK and a harbinger of European federalism threatening British sovereignty. The compromise agreed in Maastricht was that most Committee members would be elected regional politicians but their status was only advisory. However, the Commission and Council of Ministers were obliged to consult the Committee on a range of policy areas including education, culture and economic cohesion, and the Committee could give an opinion on any EU matter whether or not asked.

The Committee was set up in 1994 and had 222 members in 1995 when Austria, Finland and Sweden joined, representation varying by size of state with 24 for the large states down to 6 for the smallest, Luxembourg. The Committee's cohesion and effectiveness is, however, curtailed by its heterogeneity, mirroring the diversity of the regions from which the members come. The main divisions within the membership tend to be along state lines, rather than regions of the same type (for example, all ‘Objective One’ regions) making common cause across different states. There are huge differences in the ‘political weight’ of members, reflecting the political status of their regions. There are also divergences between regional politicians and local representatives of cities and municipalities which divide the regions; to minimise this problem the Committee presidency and deputy presidency alternate between representatives of important regions (for example, Catalonia or Lombardy) and those from the big municipalities (for example, Barcelona or Milan).

The EU's ‘subsidiarity’ principle gives precedence to lower territorial ‘levels’ of government over higher ones – at least in theory. Thus the EU as a whole should take action only where individual states cannot act effectively, an idea supported by ‘anti-federal’ British governments and so-called ‘eurosceptics’. However, on the continent subsidiarity is interpreted more positively as a federal principle which gives rights to the smaller, constituent parts of a state including sub-state regions. In 1995, a Committee of the Regions report, overseen by the Catalan President, Jordi Pujol, proposed that it should automatically extend not only to state level but to sub-state level as well:

the Community shall take action, in accordance with the principle of subsidiarity, only if and so far as the objectives of the proposed action cannot be sufficiently achieved by the Member States, or by the regional and local authorities endowed with powers under the domestic legislation of the Member State in question.

(Wagstaff, 1999b, p.192, emphasis added)

This was followed in 1997 by another report, ‘Regions and Cities: Pillars of Europe’, prepared by the leader of Bavaria's regional government and the Mayor of Oporto, and it was the basis for a Committee of the Regions ‘summit conference’ before the Amsterdam Treaty negotiations. The Treaty however did not extend automatic subsidiarity to the regions, but it did further increase the Committee's freedom of action; the main gain was the addition of more obligatory spheres, such as environmental and social policies, on which the Committee had to be consulted.

There has therefore been a remarkable historical trend of increasing regionalism, given a recent boost by globalisation and European integration. But the question remains: what is its significance, where is it all leading?

4.5 Summary

The EU as presently constituted is itself a product of globalisation, and here the impact of globalisation has been heightened by the central institutions of the EU directly encouraging regionalism and cross-border cooperation between regions to further its own political and economic integration.

Regionalism has also been indirectly boosted by other EU policies, particularly the development of the Single European Market since the late 1980s.

Activity 3

What, according to your understanding of this section, are the specifically EU factors which have contributed to the growth of regionalism?

Answer

The argument is that both the EU's regional policies, and what we have called the ‘regional engagements’ of its central institutions, have contributed. The EU has seen its work on the regions as advancing EU cohesion and integration. Meanwhile, regions have seen the EU as a way of gaining, not just resources, but greater autonomy from their existing states.

5 Toward a ‘Europe of the Regions’?

5.1 Introduction

The significance of regionalism hinges on empirical questions about the probable future of the EU and normative questions about the (un)desirability of different models for the future. A return to the traditional ‘Europe of Nations’ (that is, nation states) model is improbable precisely because of the growth of regionalism, as well as the firm establishment of the central institutions of the EU. On the other hand, because of the continuing power of states and their major say in European integration, the federalisation process will probably be ‘arrested’ long before the arrival of the ‘Federal Europe’ super-state model (Anderson, 1996). If so, the most plausible of the three dominant models would seem to be the ‘Europe of the Regions’.

However, when it is claimed, explicitly or implicitly, that regions will replace the Europe of nation states, problems immediately arise. So here it is essential to distinguish the growth of sub-state nationalist and regionalist politics, an established reality in Western Europe, from what I consider the ultimately implausible ideology of a ‘Europe of the Regions’.

5.2 The regionalism project

The regionalism project has normative as well as empirical elements – it says what ought to happen as well as what will happen – and its normative origins pre-date its contemporary usage in advocating European integration. It is open to criticism on these different grounds.

It presents a benign vision of regions and regionalism replacing or displacing nation states and nationalism. Strong versions proclaim the ‘death of the nation state’ and the ‘end of territorially based sovereignty’, while in weaker versions such ideas are only implicit, or the decline of states in favour of regions is seen as a relative, long-term matter. In EU circles weaker versions prevailed, not only because they are more plausible but also because the Commission's objective was to make allies in the regions rather than enemies in the states, which retained control over the general direction and pace of integration. However, the stronger version had more resonance at a popular level.

Empirically, the regionalist project suggests that the growing importance of a level of government between the levels of local municipality and the nation state is a trend which will continue inexorably and at the expense of nation states. It exaggerates this trend, and it inappropriately sees the relationship between regions and states as a simple ‘zero-sum game’, where more power to regions must mean less to states as if there was a fixed amount of ‘power’ that they had to fight over.

Regionalism, rather than being some independent rival, continues to be conditioned by the states. They define the regions, and in most cases still set the limits within which regionalism is possible. Far from being a preferable ‘alternative’ to the system of states, we have seen that the great diversity of regions and regionalisms often constitutes a poor basis for unified policy or cooperation. The Committee of the Regions has, for example, been hampered by the great heterogeneity and unevenness in the interests, power and democratic legitimacy of the regional representatives. The ‘death of the nation state’, like that of Mark Twain, is greatly exaggerated (Anderson, 1995). The member states of the EU largely control the direction and pace of EU integration, which is still mainly harnessed to their interests, and still dominated by the meetings of Heads of Governments and the Council of Ministers. Indeed, in some respects it has strengthened rather than weakened the member states, giving them more leverage over economic forces than they would otherwise have. Nor does regionalism necessarily weaken states. Spain, for instance, is arguably stronger as a result of devolving powers to Basque and Catalan parliaments, and it would be nonsense to argue that federal Germany is a ‘weak’ state because of its strong regions, or that Greece and Portugal are ‘strong’ because they are highly centralised. States in general have lost some economic power because of globalisation, but contrary to neo-liberal ideology they continue to have crucial roles in supra-state and sub-state developments.

The normative idea that regions are good in themselves and better than states or larger entities is also suspect for related reasons. The regionalist project suggests that regions in Europe express ‘diversity within unity’, that regions are economically efficient and powerful units yet close and cosy for politics and identity, that they express respect for cultural difference and are democratically responsive to local aspirations, and that regionalism provides a peaceful alternative to nationalism and national conflicts over sovereignty and territory. The contrast (sometimes implied rather than explicitly asserted) is with the supposedly greater economic inflexibility and inadequacy of ‘distant’ state institutions and policies, and a more bureaucratic Brussels where the Council of Ministers meets in secret. Such normative regionalism is not confined to the ‘Europe of the Regions’ project, but it is well exemplified by it.

5.3 Origins of the regionalist project

The origins of the regionalist project can be traced back to Leopold Kohr's The Breakdown of Nations, first published in 1957 (Kohr, 1986). By ‘nations’, Kohr actually meant nation states and in particular big states, for his book was a polemic against the ‘bigness’ of states as the source of modern ills. Indeed he saw excessive size as the main cause of all social problems and his ideas would later be successfully popularised by E.F. Schumacher's slogan and best-seller Small is Beautiful (Schumacher, 1973). The more recent adaptation of this idea to regions has several different sources which may help explain its appeal.

In part, the ‘Europe of the Regions’ model was developed as an ideology of EU integration and legitimation. Its rhetoric served to overcome, minimise or obscure some of the problems involved in creating the SEM after 1986, and later Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) as envisaged in the 1991 ‘Maastricht Treaty’. For example, in 1991, the Chef de Cabinet to the Regional Commissioner argued for a new Europe where regional authorities had greater political autonomy: ‘The Europe of the regions is already a cultural reality and in the new European single market there will soon be an economic one. Why not turn it into a political reality too?’ (see Harvie, 1994, Chapter 5). The idea was vigorously propagated by the ‘Four Motors’, and it lent heavily on their reputation for ‘success’ and that of other exceptional regions such as Emilia Romagna, rather than on more typical cases.

In the early 1990s the EU faced a legitimacy crisis as it sought to speed up integration. The Parliament was weak and perceived to be weak, and the Commission needed additional popular support. Linking regional identity to a putative European identity suggested a new more democratic EU, and it helped counter the largely top-down nature of integration and the perception that EMU would lead to a centralisation of economic power. It downplayed the difficulties faced by peripheral economies, particularly in times of economic depression when ‘core’ and ‘periphery’ generally diverge; and it provided a counter-balance (at least ideologically) to the neo-liberalism of the SEM and the threat it held for weaker regions, particularly as substantial help for them was ruled out by the dominant neo-liberalism.

Both the EU and the regions gained legitimacy by working directly together, and the normative ideology was picked up by interests in the regions themselves for their own reasons. A ‘Europe of the Regions’ would further the autonomy or even independence of places such as Scotland and Wales ‘in Europe’; it would help in creating regionalism in England and reforming the unwritten constitution of the British state with its archaic conception of sovereignty as the indivisible preserve of the Westminster Parliament.

The 1997-2007 Labour governments' programme of constitutional reform has involved, among other things, the creation of a Scottish Parliament and a Welsh Assembly (1999). It has also made possible through the Belfast Agreement (10 April 1998), and later the St Andrews Agreement (2006), the establishment of a devolved parliament in Northern Ireland.

When EU President Jacques Delors propagated the idea of a ‘Europe of the Regions’ he was supported by the Northern Irish MEP, John Hume, who counterposed to the ‘Europe of Nations’ of De Gaulle and Thatcher ‘a Europe which is much more comprehensive in its unity and which values its regional and cultural diversity while working to provide for a convergence of living standards’ (Hume, 1988, pp.48, 57). It was predicted that in the 1990s we would ‘leave the Europe of competing nationalisms behind us’; the nation state would break up and we needed to move beyond it to ‘a European federation of equal regions’ (Kearney, 1988, pp.8, 15–18). But a Europe of ‘equal regions’ is a utopian non-starter if ever there was one; and far from ending nationalism, some of the strongest regional movements – in Scotland, Ireland, the Basque Country and elsewhere – are themselves nationalisms whose core supporters seek not merely their own region but their own, reconstituted nation state.

5.4 Weaknesses of the regionalist project

In normative terms, as with empirical reality, regions are not necessarily more desirable than states, and in some respects could be distinctly worse. Despite the many shortcomings of existing states, it is by no means self-evident that regions would fare better in the face of global forces, and most regions, being significantly weaker than their states, would arguably be significantly less effective in delivering economic welfare, cultural and other rights. Such rights may be decreasing in existing states but the capability of these states is still much more substantial than that of any foreseeable regional alternatives. A ‘Europe of the Regions’ could indeed turn out to be a multiplicity of smaller competing units all ‘beggaring their neighbours’, and without the possibility of the state-organised regional transfers or cross-subsidies which are still generally much more important to disadvantaged regions than EU aid. While the German Länder are very powerful, it was the German state which made the crucial (albeit inadequate) resource transfers to former East Germany.

As with ‘new regionalism’ (see Section 2), the ‘Europe of the Regions’ project has the same dangers of underestimating the continuing economic importance of the state, overestimating the coherence of most regions, and conceding too much ground to the dominant neo-liberal ideology which would weaken the state's intervention and redistributive capabilities. Indeed, in some richer regions (for example, in northern Italy), regionalisms have been partly motivated by opposition to transfers from themselves to despised poorer regions, and nationalism has no monopoly on supremacist racist attitudes. Contrary to the benign vision, some regionalisms can be very parochial, even xenophobic, as well as progressive – they are not inherently either one or the other. As for the question of Europe's future, the answers on empirical and normative grounds suggest that it is unlikely to be a ‘Europe of the Regions’. It seems equally as unlikely as a return to the ‘Europe of nation states’ model, or the development of a fully-fledged federal ‘United States of Europe’ super-state.

5.5 Summary

The idea that regions are replacing nation states and that the future of Europe lies in a loose, decentralised federation of regions is a misinterpretation of recent and current developments.

This ‘small is beautiful’ ideology of a ‘Europe of the Regions’ can be rejected on empirical and normative grounds: it is still largely the existing member states which control EU integration and define the regions; the strongest regional threats to nation states come from nationalist movements wanting their own ‘nation state’; most regions would be too weak to cope with the pressures of globalisation; and their very diversity rules them out as a replacement for nation states.

Section 5 brings the discussion to a head. We have suggested that neither a return to a ‘Europe of Nations’ nor a Federal European super-state is likely. Of the three models under discussion, a ‘Europe of the Regions’ is the most plausible. But this has also been rejected as a likely outcome.

Activity 4

A key skill in any kind of academic study is to be able to summarise an argument, and then assess it critically by looking for flaws in the evidence or in the logic. That is what you should do here. As a final exercise, try to answer these two questions:

Briefly summarise the main points of the argument against the likelihood of a ‘Europe of the Regions’.

Answer

The idea is more normative (what some people would like to happen) than empirical (what will happen).

The trend towards regions growing in importance has been exaggerated.

The thesis about the decline of the nation-state has also been over-stated.

Moreover, it is not a zero-sum game: regions do not simply gain at the expense of states. For example, devolving power to a region might strengthen rather than weaken states.

States continue to define the powers of regions: hence they set the limits on regionalism.

And it is states who still control the direction and pace of European integration.

Regions are too varied in their interests, power, and democratic legitimacy to combine effectively in pursuit of their interests.

Activity 5

Can you think of any counter-arguments?

Answer

In this course we have claimed that ‘weaker’ versions of regionalism have been favoured in EU circles, partly because the Commission wanted ‘allies in the regions rather than enemies in the states’. This claim sounds rather logical and attractive, but no evidence is cited for it.

It has also been suggested that ‘the stronger version had more resonance at the popular level’. Whilst there may have been evidence for this from Scotland and Catalonia, one could equally argue that it has been notably absent from popular demand in Denmark, the Netherlands, Portugal and so on.

We have attacked John Hume's conception of a ‘European federation of equal regions’ that would leave competing nationalisms behind, because regions are unequal in power and resources. However, in the USA the 50 constituent states vary enormously in terms of geographical area, wealth and population, but it could be claimed that each of them has some claim to equality with the others in terms of domestic policy making.

It is too simple to say that states set the limits to regionalism. Whilst they may have dictated the original constitution or devolution settlement, regional autonomy can generate its own momentum. In the cases of Scotland, Catalonia, Flanders or even Northern Italy, the movements towards independence may become so powerful that states are simply unable to control them.

6 Has the future already arrived?

6.1 The complexities of a multifaceted Europe

If the ‘Europe of the Regions’ model is also ruled out – at least in its stronger versions which suggest that nation states are being replaced – the interesting question remains: how will significantly enhanced regionalisms relate to other ‘possible Europes’? These include the traditional ‘nation state’ and ‘Federal Europe’ models, both of which also reflect some continuing elements of reality, but in addition a ‘Europe’ of cities, of cultures, of national and ethnic minorities, and of transnational movements and structures which extend well beyond the institutional architecture of the EU. This multifaceted Europe is not captured by any of the three ‘models’, most obviously because they are too simplified. But, more fundamentally, they fail because they each focus on one of three ‘traditional levels’ of territorial government as if the future involved simply making a choice between these levels. They counterpose them as discrete ‘alternatives’ rather than focusing on how they interrelate, and how particular social processes span or include the different levels. They fail to appreciate the qualitative transformation in their interrelationships that is already well underway.

Political power and government are seen very simplistically in terms of a ‘zero-sum’ competition between discrete territorial levels, with more power at one level automatically meaning less at another. But political restructuring cannot be reduced to this simple arithmetic – there is no ‘fixed total’ of power to be distributed, and power is not only distributed between political institutions at different spatial scales, it is also located in the relations between these institutions and it is found outside them in civil society. As Susan Strange pointed out, nation states may be losing some of their autonomy not because power has ‘gone upwards’ to other political institutions such as the EU but because it has ‘gone sideways’ to economic institutions and global market forces, and in some respects it has ‘gone nowhere’ or just ‘evaporated’ as political control over economic forces is simply lost (Strange, 1994). Likewise, more power for regions does not necessarily mean less for states. We have seen that states may indeed be strengthened by devolving some political processes to their regions and by ‘pooling’ some of their sovereignty in the EU collective. Furthermore, while states may lose some autonomous power in one policy area (for example, industrial development), they may gain new powers in other areas (for example, labour training, and controls over labour migration), and such distinctions are increasingly important given the fact that globalisation is having very uneven impacts on different state functions. So the idea of the EU or the regions as alternatives to the nation state would seem to be fundamentally flawed.

The traditionalist limitations of this idea are well depicted by the metaphor of ‘Gulliver's fallacy’, in which new political forms can only be scale replicas of the existing nation state, either larger as in a ‘United States of Europe’, or smaller as in regional government (just as the two societies which Gulliver met in his Travels, one of giants, the other of midgets, were simply scale replicas of human society). This perspective sees only a change of geographical scale with no real appreciation that political processes and institutions at different scales are likely to be qualitatively (not just quantitatively) different, and no recognition that their new interrelationships may be a key factor potentially transforming the whole nature of politics. Much of the debate about Europe's future is vitiated by false polarisations between regions, states and other territorial levels.

Instead, it seems more fruitful to think of qualitative changes in the relationships within and between such levels, and to see them as being increasingly linked in ‘multi-layered’ or ‘multi-level’ structures of governance, with multiple identities and loyalties, albeit ones of varying intensity or importance (Guibernau, 1999). We also need to take into account the fact that regionalism, along with other territorial forms of politics, culture and identity, is increasingly in interaction with non-territorial transnational movements which cross-cut these levels.

6.2 Looking forward

The sovereign authority of states has not been replaced, nor is it likely to be in the foreseeable future, but it is already significantly less clear-cut than it was only some decades ago. Rather than sovereignty being based on a single territorial level, whether that of the state or a scale replica, we are more likely moving toward a situation of segmented, overlapping or shared authority, where regions are one level among several territorial and non-territorial political entities.

A fully federal ‘United States of Europe’ seems highly unlikely in the foreseeable future. The states would hardly agree to ‘sink their differences’ in a federal state, not least because of uneven regional development and the fact that the pace of cultural unification in Europe has not been at all commensurate with the moves toward economic union. All the states, and some of the regions, remain important as repositories of distinct cultures. Equally, and for similar reasons, the nation states are not about to acquiesce to a ‘post-nationalist’ and loosely federal ‘Europe of the Regions’. The comparative importance of the different territorial levels will continue to change, perhaps in unpredictable ways, and in some policy areas both the EU and the regional levels may continue to gain relative to the states. But the broad outlines of more complex multi-level governance and multiple identities are already visible in present structures and relationships. In that sense the future has already arrived.

6.3 Summary

None of the three models – national, federal or regional – can adequately capture the complexity of the multifaceted Europe of today. Each implies an exclusive distribution of power between the levels of territorial governance that is too simplistic.

We need to think in terms of qualitative changes in the relationships within and between the levels and see them as being linked in multi-layered structures of governance.

Such a complex multi-level governance system, with multiple identities and loyalties, may already be with us.

7 Conclusion

7.1 Summary of Sections 1–3

In summary, this course has endeavoured to substantiate a variety of related points which epitomise current trends and problems in governing European diversity.

‘Regions’ and ‘regionalism’ in Western Europe display great diversity in economic, social and cultural terms, within particular states as well as between states; regions vary widely in size, population, levels of development, history, identity and politics (or lack thereof). But since the heyday of the centralised nation state in the 1930s and 1940s, most of Europe's regions have politically grown increasingly more important. This has been largely in response to regional inequalities in economic development, threats to traditional regional cultures, and the political federalisation of states, whether to reduce their centralised power or to contain regional separatisms.

More generally, since the 1970s, accelerated globalisation has meant that attracting external sources of investment became more crucial and this has made ‘global’ or at least ‘international’ players of regional (and local) authorities which previously had acted largely with and through their central governments. These developments have advanced furthest in the European Union, whose central institutions have directly encouraged regionalism and cross-border cooperation between regions to further the EU's political and economic integration. Regionalism has also been indirectly boosted by other EU policies, particularly the development of the Single European Market since the late 1980s.

7.2 Summary of Sections 4–6

However, the idea propagated in the 1990s that Europe's future lies in a loose, decentralised federation of regions, and that regions are replacing nation states (allegedly too small for global competition but too big for cultural identification, apparently being eroded ‘from above’ by globalisation and the EU and ‘from below’ by regionalism, and inherently associated with nationalistic conflict), is very misleading. Notwithstanding the problems of nation states and nationalism, in our view this ‘small is beautiful’ ideology of a ‘Europe of the Regions’ can be rejected on empirical and normative grounds: the existing member states still largely control EU integration; they define the regions; the strongest regional threats to nation states come from nationalist movements wanting their own ‘nation state’; most regions would be less able to cope with the pressures of globalisation; and the great diversity of regions undermines any possibility of them replacing nation states.

Instead of the future lying unambiguously with regions, or with a European super-state, or a return to the traditional Europe of nation states, it is much more likely to resemble the multi-level present. Regions will continue to develop but through complex interactions with the EU, the member states, other regions and cities, and non-territorial associations which span these different territorial ‘levels’.

References

Acknowledgements

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Course image: VISITFLANDERS in Flickr made available under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Licence.

Wagstaff, P. (ed.) (1999) Regionalism in the European Union, Intellect Limited;

Adabted from Wagstaff, P. (ed.) (1999) Regionalism in the European Union, Intellect Limited;

Don't miss out:

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University - www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Copyright © 2016 The Open University