1 Interrogating the British state

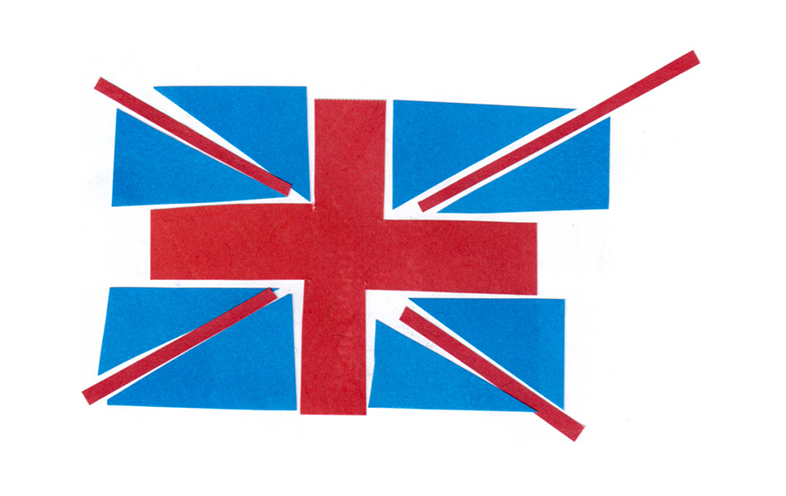

In some ways even the notion of Britain (and hence Brexit) can be seen as problematic. ‘Britain’ is, of course, not a political entity in its own right and even Great Britain (defined to include England, Scotland and Wales) is only a part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, which is made up of a series of quite distinct territories. Brendan O’Leary (2016, p. 518) has gone so far as to argue that, ‘To use BREXIT is to do verbal violence to the nature of the UK, which is a double union, not a British nation-state’. He favours the term ‘UKEXIT’.

One common way of understanding the UK state has been to see it as a unitary – or centralised – one. That is, one in which all power flows from the centre, from Parliament in Westminster. Because the UK does not have a written constitution, it is assumed that its Parliament (or strictly speaking the Crown in Parliament) is sovereign, able to decide on any policy or piece of legislation. The role of government becomes to implement it throughout the kingdom. But matters have always been more complex and uncertain than that. So, for example, the EU can be seen as one recent constraint on that power and the demand to ‘take back control’ which was so significant in the Brexit campaign reflected a popular concern about that.

However, it is also important to recognise that the UK’s own formation has left important legacies, as a result of which its component parts have some distinctive arrangements and characteristics of their own. There is a long and uneasy tradition of self-rule in Northern Ireland (dating back to its formation in the wake of Irish independence), which has generated a particular set of political arrangements and institutions. And Scotland’s legal, education and religious systems have always been distinctive. These aspects of social and political life have become still more institutionalised and have developed further in the context of processes of devolution since the late 1990s. These have led to the creation of the National Assembly in Wales, the Scottish Parliament and a rather different settlement for the Northern Ireland Assembly. The form taken by devolution has been different in each territory, but the limits being placed on the decision-making powers of Westminster are clear enough, even if formally the Westminster Parliament may claim ultimate authority.

There are no specific government institutions for England. There is no separate English Parliament, although there are now issues that are deemed only to affect England (or England and Wales) on which only MPs elected for English constituencies may vote (or English and Welsh MPs, where appropriate). But in a sense, England’s constitutional position reflects the extent to which England has in practice been positioned as the norm against which other national formations are assumed to define themselves. For many years it was not uncommon for England and Britain to be used interchangeably in popular speech, at least in England and by many of those commenting from outside the UK. So, for example, the UK’s current Queen is always identified as Queen Elizabeth II, although the first Queen Elizabeth was only Queen of England and Wales (which had already been incorporated into England). England was understood to be the foundation on which Britain, Great Britain and the United Kingdom were built. Tom Nairn has powerfully identified what he sees as ‘the core of the problem’ with this, in arguing that:

… behind England’s Britain there lies England’s England, the country which has not merely ‘not spoken yet’, but, in effect, refrained from speaking because a British-imperial class and ethos have been in possession for so long of its vocal chords (Source: Nairn, 2000, p. 100).

It may be, of course, that for the first time the referendum has enabled that ‘England’ to speak.

Each of the UK’s nations and territories has its own distinctive history. Not only is that reflected in the pattern of the referendum vote, but the vote also highlights the extent to which the UK needs to be understood through its divisions as much as through what holds it together.