Social marketing

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 20 April 2024, 4:07 PM

Social marketing

Introduction

This OpenLearn course examines the nature of social marketing and how the adoption of marketing concepts, frameworks and techniques developed for commercial marketers can be applied to the solution of social problems. Primarily, social marketing aims to effect behavioural change in the pursuit of social goals and objectives, as opposed to financial or other objectives.

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course B324 Marketing and society

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

describe and explain the meaning and nature of social marketing

analyse social marketing problems and suggest ways of solving these

recognise the range of stakeholders involved in social marketing programmes and their role as target markets

assess the role of branding, social advertising and other communications in achieving behavioural change.

1 Course overview

Never before have social issues been more at the centre of public and private debate than at the present. From concerns about sustainability and the future of the planet to the introduction of smoking bans, from actions to combat ‘binge drinking’ and childhood obesity to programmes designed to prevent the spread of AIDS in developing countries, there is a growing recognition that social marketing has a role to play in achieving a wide range of social goals. In the UK, for example, the National Social Marketing Centre (NSMC) has recently been established by the Department of Health and the National Consumer Council. You may wish to visit the website at (accessed 9 May 2008), which illustrates the interest in social marketing and health issues.

From May 2008 the Open University Business School is offering a new course: B324 Marketing and society. It includes three main areas: social marketing (40 per cent of the course), marketing ethics (30 per cent of the course) and responsible business marketing (30 per cent of the course).

This OpenLearn course examines the nature of social marketing and how the adoption of marketing concepts, frameworks and techniques developed for commercial marketers can be applied to the solution of social problems. Primarily, social marketing aims to effect behavioural change in the pursuit of social goals and objectives, as opposed to financial or other objectives. Two journal articles, ‘Broadening the Concept of Marketing’ by Kotler and Levy (1969), and ‘Social Marketing: An Approach to Planned Social Change’ by Kotler and Zaltman (1971) generated early interest in the subject. Since then a growing body of research and theoretical development has focused on effecting behavioural change across a range of social issues.

This course focuses on four key questions:

Why is a social marketing approach relevant and necessary in today's environment?

How can an understanding of consumer/human behaviour help to develop appropriate actions and interventions?

Who are the target markets for social marketing programmes?

What is the role of marketing communications and branding in achieving behavioural change?

The aims of this course are to:

explore how marketing concepts and techniques can be applied to the marketing of social issues as opposed to the more traditional area of commercial marketing;

examine how social marketing approaches can change behaviour in order to achieve socially desirable goals;

illustrate, through case study examples, the application of concepts and techniques to ‘real world’ social marketing problems.

2 Understanding the nature of social marketing

2.1 Definitions of marketing

Before we focus on ‘social marketing’ we should clarify the nature of ‘marketing’ as both an academic discipline and a management practice.

Kotler and Armstrong (2008, p. 5) define marketing as follows:

Marketing is human activity directed at satisfying needs and wants through exchange processes.

Two key issues are highlighted by this definition:

i. Exchange – most explicitly noted in Kotler and Armstrong's definition is the core element of exchange. In commercial marketing the nature of the exchange is usually clear, i.e. a product or service for money. Although a closer analysis often reveals that even here things are not so simple, for example the price can be considered to include time spent in obtaining the product.

ii. Customer satisfaction – The pivotal construct in marketing is that of customer satisfaction. Commercial marketers aim to satisfy customers to a greater extent than the competition. Satisfaction is considered to lead to behaviour such as positive word of mouth, repeat purchase and ultimately profitability. In this definition, this is illustrated by reference to needs and wants.

Other fundamental elements of ‘marketing’ are:

iii. Goals and objectives – Marketing exchange takes place so as to achieve the goals of the buyer and the seller. For commercial marketers these goals may be profit, market share, etc.; for the individual the goals may be the self-esteem achieved by buying an expensive car. A major difference between commercial and social marketing lies in the difference in the nature of the goals and objectives. Here the goals are society's goals.

iv. Process – Many other definitions of ‘marketing’ emphasise the processes which the marketer must undertake. Customer needs and requirements must be identified, i.e. through a process of market research, and then supplied through the development of a product which is supplied at the right price, through appropriate channels and with effective promotion.

v. The product – The focus of the exchange. Goods, services, ideas, people, etc. may be exchanged. This is a more comprehensive approach than the typical commercial focus on only goods and services. A key issue for social marketers is to define the nature of their product, i.e. exactly what are people buying when they adopt new behaviours such as recycling or stopping smoking?

2.2 So how can social marketing be defined?

The definition offered by Kotler, Roberto and Lee (2002, p. 5) is a useful one:

The use of marketing principles and techniques to influence a target audience to voluntarily accept, reject, modify or abandon a behaviour for the benefit of individuals, groups or society as a whole.

Social marketing relies on voluntary compliance rather than legal, economic or coercive forms of influence.

Kotler et al. (2002) argue that social marketing is often used to influence an audience to change their behaviour for the sake of one or more of the following:

improving health – health issues

preventing injuries – safety issues

protecting the environment – environmental issues

contributing to the community – community-building issues.

Lazer and Kelley (1973, p. ix) define social marketing as follows:

Social marketing is concerned with the application of marketing knowledge, concepts and techniques to enhance social as well as economic ends. It is also concerned with analysis of the social consequences of marketing policies, decisions and activities.

This definition adds a further dimension to the scope of social marketing. Sometimes described as ‘critical marketing’, this involves an assessment of (usually) commercial marketing's impact on society. This course will, however, concentrate on the first element of the definition, i.e. the use of marketing to achieve social goals.

Activity 1

Think for a moment about examples of social marketing with which you are familiar.

Discussion

One of the most obvious examples in the UK is that of the anti-smoking campaigns. Here it is important to note Kotler and Zaltman's (1971) point that social advertising and social marketing are not the same thing. From the public's perception this is often the ‘face’ of social marketing, but for the marketer many other issues must be taken into account, as discussed later in the course. Other examples relate to the many global initiatives to reduce energy consumption/carbon emissions; encourage recycling; reduce binge drinking and childhood obesity; encourage positive health behaviours; and many more.

2.3 Reasons for social marketing

Your thoughts should already have suggested reasons why social marketing can be an effective approach to dealing with social problems and issues. We will now consider some of these and also arguments against the use of marketing within this context. Three key reasons for adopting a social marketing approach are:

The power of marketing – The power of marketing principles and techniques in the hands of the commercial sector cannot be denied. Most of us, including very young children, recognise logos and brand names, even for products which we never buy. These symbols occupy our minds and form part of our socio-cultural context. Many of us will spend our hard-earned money by paying well above the functional utility price of a product in order to acquire a specific brand name which means something to us. Consider, for example, how branding plays a role in our choice of foodstuffs, soap powder, clothing, watches and cars. Communication through the various media is clearly very powerful, consequently it would seem negligent, to say the least, not to adapt this power to society's good. As Gerard Hastings' (2007) book title says – ‘Why should the Devil have all the best tunes?’

Track record/evidence – There are many examples of social marketing applications which have been successful in achieving positive behavioural change. We will look at some of these throughout the course.

Not an option – As Kotler and Levy (1969) argue in their article, ‘the choice … is not whether to market or not to market … The choice is whether to do it well or poorly’ (p. 15).

2.4 Reasons against social marketing

Arguments against the use of social marketing can be based on the following:

Cost – Social marketing programmes can cost considerable amounts of money. Criticisms of these expenditures are heightened as they are often financed by public money in times of resource constraints and therefore have a high opportunity cost. A related issue is that of the problems involved in assessing the success of these programmes. The long term nature of behavioural change and the difficulties in establishing cause–effect relationships add to the fuel for the critics.

Misconceptions and negative attitudes about marketing – As most introductory marketing text books relate, marketing is often equated with selling and persuading people to buy things that they do not really want. Interestingly, when people are asked if they have been persuaded they usually say no. Today's adoption of marketing principles and techniques (for example, market segmentation, market research, branding) by the banking sector is now evident. It was not too long ago, however, that bank managers were describing such activity as ‘nauseating’, ‘odious and irrelevant’ and ‘an over-rated pastime’ (Turnbull and Wootten, 1980, p. 482). Many professional services such as accountants and solicitors still equate marketing with advertising (Barr and McNeilly, 2003). Public sector organisations, such as hospital trusts, have also been slow to adopt (Meidan et al., 2000). Lack of awareness of the potential of marketing, misunderstanding and the observation of some of the more doubtful practices of the commercial sector are some of the reasons behind this. As previously mentioned, the criticism of commercial marketing is an element of social marketing, and this is highlighted in the Lazer and Kelley definition (see Section 2.2). A final reason for resistance to marketing may be due to the nature of the language. Strategic marketing, for example, adopts the terminology of Sun Zu's ‘The Art of War’ (Krause, 1995). Phrases such as ‘flanking defence’, ‘encirclement’ and ‘full frontal attack’ are probably not particularly attractive to the World Wildlife Fund or Oxfam.

Parameters of marketing activity – A final point emerges from marketing authors themselves. In response to Kotler and Levy's article ‘Broadening the Concept of Marketing’, Luck (1969) argued that the wider application of marketing away from the commercial sector dilutes the content and nature of marketing as a discipline. There are few proponents of this view, however, and the last four decades have seen many applications including, of course, the application of social marketing.

3 Understanding consumer behaviour

3.1 Introduction

Andraesen (1995) states that for the social marketer ‘consumer behaviour is the bottom line’ (p. 14). In order to understand how to develop programmes that will bring about behavioural change we need to understand something about the nature of behaviour. The consumer behaviour literature typically borrows from the fields of sociology, psychology and social anthropology amongst others. There is a vast, and growing, body of knowledge on the subject and a few of the main elements will be discussed in this section.

Key elements of consumer behaviour include:

analysis of the factors which influence behaviour.

the role of motivation and attitudes.

consumer behaviour models.

Activity 2

Before we look at these, use the Government and Social Research website to research some of the core theories:

stages of change

social cognitive theory

exchange theory

You will find the information you need from Civil Service

3.2 The factors which influence consumer behaviour

A large number of factors influence our behaviour. Kotler and Armstrong (2008) classify these as:

Psychological (motivation, perception, learning, beliefs and attitudes)

Personal (age and life-cycle stage, occupation, economic circumstances, lifestyle, personality and self concept)

Social (reference groups, family, roles and status)

Cultural (culture, subculture, social class system).

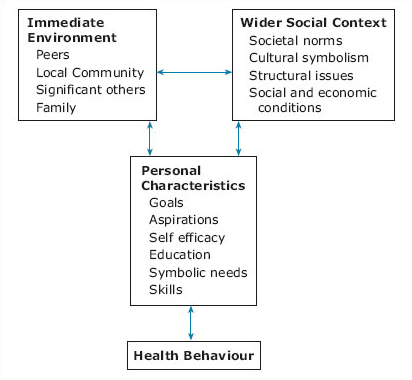

Below you will see Figure 1, which adapts the above factors to a health behaviour context, providing a model which also explicitly emphasises, together with cultural factors, other features such as the economic environment as an element of the wider social context.

As you can see, the immediate environment approximates to Kotler's social factors. Many studies of both commercial and social marketing emphasise the influence of family, friends and others on our decisions. Peer group pressure is an important influence and may be negative or positive.

Figure 1 illustrates an approach known as social-cognitive theory which is based on the proposition that our behaviour is determined by both personal and environmental factors.

3.3 The importance of understanding motivation

Personal characteristics in Figure 1 combine both psychological and personal factors. Two important factors which drive behaviour are motivation and attitudes.

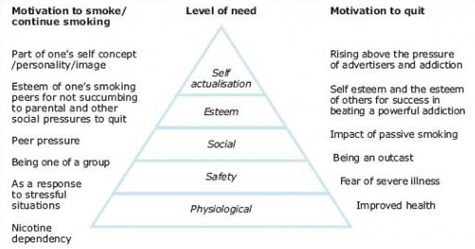

MacFadyen et al. (1998) (see Figure 1) emphasise the role of goals, aspirations and symbolic needs. Many of you will be familiar with theories of motivation and how they explain why we engage in a particular behaviour in order to achieve our goals and satisfy our needs. There are many theories of motivation. You may have come across these in other studies of marketing, human resource management or elsewhere. Motivation theories seek to explain why we do the things we do either by examining how a behaviour satisfies our ‘needs’ or the processes we go through as we decide how to achieve our goals. One of the best known of motivation theories is that of Maslow's (1943) theory of human motivation or hierarchy of needs. The five original needs comprised those listed below and are illustrated in the typical hierarchical approach in Figure 2a.

Physiological needs: These are the basic needs of the organism such as food, water, oxygen and sleep. They also include the somewhat less basic needs such as sex or activity.

Safety needs: Here Maslow is talking about the need for a generally ordered existence in a stable environment which is relatively free of threats to the safety of a person's existence.

Social (love) needs: These are the need for affectionate relations with other individuals and the need for one to have a recognised place as a group member – the need to be accepted by one's peers.

Esteem needs: The need of a stable, firmly based self-evaluation. The need for self-respect, self-esteem, and for the esteem of others.

Self-actualisation needs: The need for self-fulfilment. The need to achieve one's full capacity for doing.

Activity 3

By reference to Maslow's hierarchy in Figure 2a, illustrate for each level of need why you think that young people (teenagers) are motivated to smoke, and why they might be motivated to quit.

Below is a printable version of the hierarchy diagram.

Click the link below to open Maslow's hierarchy.

Discussion

In addition, money could be a motivator at various levels, e.g. spending money saved on family or friends (social needs) or to avoid debt (safety needs) or to achieve self esteem through purchase of an expensive mobile phone.

3.4 The importance of understanding attitudes

One of the most important phenomena for a social marketer to understand is that of ‘attitudes’. Having said this, this is not a straightforward issue as there is much disagreement about the nature of attitudes, how they are formed, and how they determine our behaviour. Attitude theory research is a key focus for consumer behaviour theorists and derives from the field of psychology.

There are many definitions of attitude, for example, ‘the predisposition of the individual to evaluate some symbol or object or aspect of his world in a favourable manner’ (Katz, 1970).

There are also differences of opinion as to what comprises an attitude. The three main elements on which theorists focus are:

- Cognitive component (beliefs/knowledge).

- Affective component (feelings).

- Conative component (behavioural).

In other words we believe/know (cognitive component) something, for example, recycling is good for the environment. We also believe that looking after the environment is a good thing. This forms our positive feelings (affect) towards recycling behaviour. We are therefore more likely to intend to engage in recycling behaviour (conative factor) and ultimately to engage in the behaviour itself.

Differences of opinion relate to which of the three components are actually part of attitude, i.e.:

Some (e.g. Fishbein, 1970) view attitude as a relatively simple unidimensional construct referring to the amount of affect for or against a psychological object (in other words the feeling element only).

Others (e.g. Bagozzi and Bunkrant, 1979) describe attitude as a two dimensional construct including the cognitive and affective component.

Others (e.g. Katz and Stotland, 1959) describe attitude as a complex multi-dimensional concept consisting of an affective, cognitive and behavioural component.

In one sense the above distinction does not matter too much since all approaches recognise the three components; it is important, however, when we come to measure attitudes to be clear as to what exactly is being measured. The most important issue for us at the moment is to be aware of the three components and how they combine to determine behaviour. Most of the research in this area is based on Fishbein and Ajzen's (1985) theory of reasoned action described in the model below.

The theories of reasoned action and planned behaviour

The extended Fishbein model, based on the theory of reasoned action, includes the following components to explain behaviour.

Attitude to the behaviour comprising:

a. The strength of the expectancy (beliefs) that the act will be followed by a consequence.

b. The value of that consequence to the individual.

This is the basic expectancy value approach. Returning to our previous smoking cessation example, if we expect that stopping smoking will result in health, wealth and happiness – and this is important to us – then we will develop a positive affect towards the behaviour of stopping smoking. There is, however, another dimension.

Subjective norms (i.e. the socio-cultural norms of other persons, groups or society) and the individuals' desire/motivation to conform to these norms. Consequently, peer group and other pressures may reduce or enhance our attitudes towards stopping smoking. Ajzen (1985) later included:

Perceived control (i.e. situational or internal obstacles to performing the behaviour). This addition has resulted in a new model – ‘the theory of planned behaviour’. Consequently, the power of addiction may impact on our attitudes and prevent us from trying to stop smoking.

A key question, for both commercial and social marketers, is: Why do actual behaviour and reported intentions often differ?

As discussed earlier, the purpose of social marketing is to effect behaviour change. Attitude models often record behavioural intentions rather than actual behaviour. One of the purposes of research is to assess how people will behave in the future, for example in response to new stimuli such as additional resources – help lines, clinics, etc. One of the problems, however, is that reported behavioural intentions often don't match up to actual behaviour.

Activity 4

List the reasons why you think that what people say they will do in answer to research questions is often very different to what they actually do.

Discussion

There are many reasons. These may include:

Reasons due to the research process, e.g. telling the researcher what they want to know out of politeness.

Reasons due to the individual's wish to show themselves to be rational or a ‘good citizen’. They might, therefore, overstate intentions to reduce environmental emissions and understate intentions to use private transport.

They may genuinely intend to engage in the behaviour but situational factors intervene, e.g. they may not have the time to travel by public transport or there may be a bus strike.

3.5 Consumer behaviour models

Many theorists have developed models of consumer behaviour. Some of these focus on the factors which influence behaviour (such as the model in Figure 1). Others emphasise the stages which consumers go through as they make their decisions to engage in a particular behaviour. Many adopt the ‘belief–feeling–behavioural intention’ behaviour model illustrated in Section 3.4.

The ‘stages’ approach has been adapted by social marketers. Theories and models help us to make sense of the world by distilling previous learning, but can never explain it perfectly. All such theories and models have their limitations and these should be recognised.

An understanding of consumer behaviour is essential to the development of social marketing programmes. There are, however, a whole range of individuals and organisations, other than the final consumer, who/which may be target markets, and these are described in the next section.

4 Stakeholders and target markets

4.1 Introduction

Greenley and Foxall (1998) emphasise that the marketing literature typically focuses on only two stakeholder groups (consumers and competitors), arguing that this should be extended to include other key stakeholders. Freeman (1984) highlights the interdependence of organisations and their stakeholders, i.e. ‘any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organisation's objectives’ (p. 46). This definition emphasises the wide range of individuals, groups and organisations who/which might have an interest in social marketing programmes.

Hastings (2007) makes a similar point when he discusses ‘moving upstream’. Discussion of social marketing typically focuses on the individual or groups of individuals whose behaviour change is the aim of the programme or activity. The social marketing network, however, involves a whole range of organisations, and others, for the social marketer to engage with as additional target markets. This is a particular issue when considering both the policy development and service delivery aspects of social marketing, for example, influencing governmental bodies to implement legislation regarding food labelling or smoking bans or GPs to offer consumer-friendly family planning services.

When developing a marketing strategy for potential/actual collaborators, the same social marketing principles and practices apply. A fundamental question relates to the nature of the exchange, i.e. why should government introduce an environmental policy or a school agree to allocate resources to prevent bullying? To put it bluntly, ‘What's in it for them?’ or alternatively, how can we achieve goal congruence between the social marketer and these upstream organisations so that behavioural change can be achieved? Once we are clear as to the target market then strategies can be developed to persuade upstream audiences that a specific behavioural change will fulfil their own goals. Here a knowledge of organisational behaviour will aid in developing a marketing plan, for example, an appreciation of the complexity of the organisational decision-making process and the range of individuals involved; power relationships and political motivations. Relationship marketing strategies, which originally developed within an organisational marketing context, are more likely to predominate over the traditional marketing mix approach. Personal representation is a key element of the communication process. Understanding individuals, their organisational relationships and motivations is crucial to effective upstream social marketing.

4.2 Stakeholder analysis

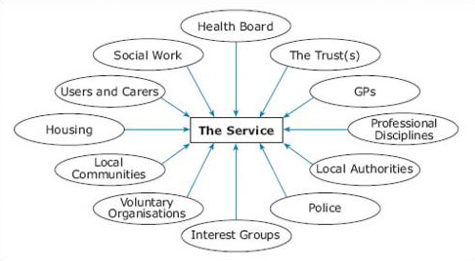

Figure 3 illustrates the range of stakeholders who could have an interest in health-related community social marketing programmes.

A major concern of decision makers is the need to balance the often conflicting expectations and interests of stakeholders. Stakeholder analysis asks:

Who are the stakeholders in a particular issue or activity?

What are the expectations and objectives of the various stakeholder groups?

What are their interests and how interested are they?

How dependent is the organisation on each group and how is this changing over time in terms of :

the degree of power (potential for disruption) that the group exercises?

possibility of replacing the relationship?

extent of uncertainty in the relationship?

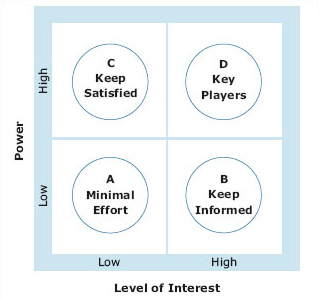

Mendelow's matrix (see Figure 4) describes four types of stakeholder. It should be noted that the classifications are context specific and dynamic, for example, stakeholders in Group C may move in to Group D if their interest in a particular project increases. Additionally, those in Group B may become empowered by access to key players, media attention, etc.

Activity 5

Read the case study entitled ‘The challenges of using social marketing in India: The case of HIV/AIDS prevention’, linked below. If you were developing this social marketing campaign, which stakeholder groups would you have to take into consideration? Use Mendelow's matrix to classify the groups according to their interest and power.

Click the link below to open the case study. (5 pages, 115KB)

Discussion

There are many stakeholder groups involved. You may have made a number of assumptions in your analysis so make sure that these have been clearly stated.

Central government – D. They have control over resources and ultimate responsibility for success. There may be lack of interest in some parts of government, or influences due to corruption, etc. …

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) – B. Low in resources but interested in the success of the programme. We do not, however, know about other sources of power such as the ability to influence or exert political pressure.

Department for International Development – as NGOs above.

Retailers/potential retailers of condoms – C. High power as they can control the supply of condoms but because of the various cultural influences they have little interest in the issue. However, as the programme proceeds they may become key players.

Consumer groups – A. The various consumer groups discussed in the case appear to have little power in influencing the nature of the programme and little interest. However, as the key target market, the social marketer would aim to shift this stakeholder group by changing perceptions to move them to the B quadrant.

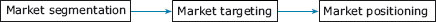

4.3 Market segmentation and targeting

Market segmentation and targeting is at the core of marketing strategy and consumers (or potential consumers) are the key stakeholder group for both commercial and social marketers. In this section we focus on those specific consumers whose behaviour is the focus of the social marketing activity.

In Section 3.2, the factors which impact on consumer behaviour were outlined.

It is these factors – e.g. age, income, lifestyle – that form the basis for market segmentation. The process is as illustrated below.

Market segmentation is the process of dividing the market in to groups of consumers who respond in a similar way to a given set of marketing stimuli (e.g. price, product features) or, alternatively, groups of consumers/customers with homogeneous needs or preferences. This may be on the basis of demographics, e.g. age, gender; geographics, e.g. by country, rural/urban areas; psychographics, e.g. lifestyle; or behavioural factors, e.g. brand loyalty.

Subsequently the organisation will select a target market based on a number of factors. For example, will the target market provide the required level of behaviour change (or meet other objectives)? Will it be accessible to the organisation taking into account the available resources, etc.?

The third stage is to position the product/organisation (a) against competitors and (b) in the minds of the consumer, i.e. arranging for a product/service to occupy a clear, distinctive and desirable place in the market and in the minds of target customers. This is achieved through product design, pricing, promotional activities, etc. Communication and branding are essential elements of a marketing programme and these are discussed in the next section.

5 The role of communications and branding in social marketing programmes

5.1 The linear model of communications

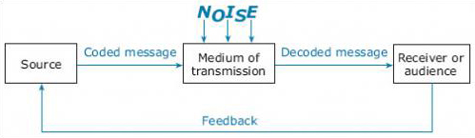

One of the key tasks of social marketers is to develop effective messages which provide individuals and organisations with the information required to achieve behavioural change. Communication represents the ‘transmission of information, ideas, attitudes, or emotion from one person or group to another’ (Fill, 2002, p. 31). There are many models and frameworks available to help with communications planning. First, an understanding of how communication works is illustrated in Figure 5.

The communication process involves:

the sender

the message itself

encoding the message into a form which can be transmitted, e.g. written, oral

transmitting the message

the receiver

decoding the message

action.

Evidently, effective communication involves the ‘sender’ of the message in encoding and transmitting the information in a way which is relevant to the target audience. Secondly, the receiver must have the ability to decode the message and to recognise the intended meaning. There should also be:

feedback, which should ensure that the receiver has decoded the message effectively by responding to the message in some way.

A final element is:

noise, anything in the environment which impedes the transmission and decoding of the message, e.g. conflicting interests, pressure of work, too many other messages.

Activity 6

Using the elements in Figure 5, list the factors which you consider may prevent effective social marketing communications.

Discussion

Barriers to effective social marketing communication may include:

Lack of understanding of the target audience by the sender. Consequently the message may be encoded using language or symbols which fail to transfer the intended ‘meaning’ to the audience. Hastings (2007) uses the illustration of an anti-heroin campaign where young people's interpretation of the results of heroin addiction were favourable, rather than as intended, because of a lack of understanding of youth culture by the advertising agency.

Inadequate definition of required feedback. The effectiveness of communications needs to be evaluated by the sender (campaign sponsors, etc.). Feedback may be defined in terms of actions, e.g. visiting a website or telephoning a smoking quit line. If no specific feedback is required then research may be conducted to assess, for example, awareness of the message.

Incorrect choice of medium/media. Possibly because of funding constraints, or again because of lack of knowledge of the consumers' media habits, the incorrect medium or media may be chosen. Media may include impersonal sources such as television, newspapers, magazines, etc. and personal sources such as professional services (doctors, teachers, etc.) and peer group members, family, etc. An important issue here is one of source credibility, i.e. ‘the extent to which a source is perceived as having knowledge, skill or experience relevant to a communication topic and can be trusted to give an unbiased opinion or present objective information on the issue’ (Belch and Belch, 2001, p. GL3).

Consistency of messages. In view of the many potential sources of communication it is vital that there is a consistency of message across the various channels. This is illustrated in the next model, which emphasises the need for integrated marketing communications.

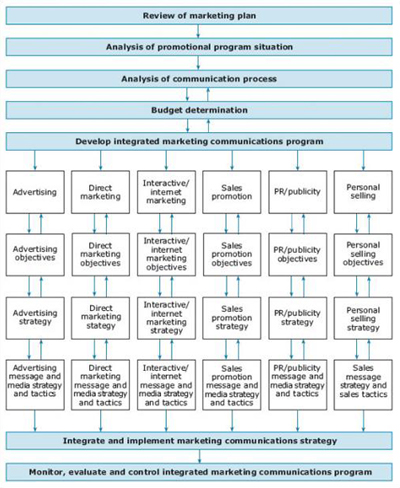

5.2 An integrated marketing communications framework

With a wide range of communications channels available to social marketers it is crucial that these deliver consistent messages. Belch and Belch (2001) describe the move towards integrated marketing communications (IMC) as one of the most significant marketing developments of the 1990s. They explain that a fundamental reason for this is the recognition by businesses of ‘the value of strategically integrating the various communication functions rather than having them operate autonomously’ (p. 12).

They adopt the American Association of Advertising Agencies definition of IMC:

… a concept of marketing communications planning that recognises the added value of a comprehensive plan that evaluates the strategic roles of a variety of communication disciplines – for example, general advertising, direct response, sales promotion and public relations – and combines these disciplines to provide clarity, consistency and maximum communications impact.

(Belch and Belch, 2001, p. 11)

The basis of this plan is illustrated in Figure 6.

The integrated marketing communications programme is developed by reference to a number of factors, i.e.

The overall marketing plan, including marketing objectives and competitor analysis.

The promotional programme situation, e.g. internally – previous experience and ability with respect to promotions – and externally – consumer behaviour analysis, segmentation, targeting and positioning decisions.

Communications process analysis – e.g. communication goals, receiver's response processes, source, message and channel factors.

Finally, the available budget and decisions with respect to budget allocation will input into the planning process.

Figure 6 illustrates six main approaches to marketing communications. We will now look at these in turn with respect to social marketing communications.

1. Advertising

Advertising can be defined as ‘any paid form of non-personal communication about an organisation, product, service or idea by an identified sponsor’ (American Marketing Association).

Advertising decisions include those relating to:

The use of the various media (TV, radio, newspapers, magazines).

How advertising can be developed for a specific target audience.

The use of rational and/or emotional appeals; in particular the use of fear appeals to transmit messages.

Activity 7

Read the section of Chapter 5, Social Marketing: Why should the Devil have all the best tunes? (linked below), and try Exercise 5.2.

Click the link below to open the section of Chapter 5. (6 pages, 1597KB)

2. Sales promotion

Whereas advertising is traditionally associated with long term brand building and can reach a wide audience, particularly with the growth in global media, sales promotion is more often considered a short-term approach to generating sales. Promotional tools include introductory offers, competitions and point of sale promotions. These approaches can be readily associated with commercial sector organisations, for example, Boots (a UK retail chemist chain) uses in-store posters to promote the benefits of stopping smoking.

3. Public relations/publicity

Similar to advertising, publicity is a non-personal form of communication, but here there is no direct payment and no identifiable sponsor. Consequently publicity may also be negative, or adverse, since the organisation, group or individual may not be able to control it. For social marketers, publicity, negative and positive, often arises in the media as a result of scientific reports dealing with issues such as childhood obesity or environmental pollution. ‘Media advocacy’, which is a term derived from public health, refers to situations where the media are encouraged to cover particular issues and consequently communicate these to the public and/or specific target markets.

4. Personal selling

In the previous section, we looked at the wide range of stakeholders who are involved in social marketing programmes. These include a number of individuals and organisations who will be responsible for providing information and communicating with target audiences. As with all communication there is an issue of source credibility, and the credence which consumers, or potential consumers, give to a particular source is of paramount importance. The role of (health) professionals in many social marketing campaigns is an important one.

5. Direct marketing

This involves direct selling, direct response advertising, telemarketing, etc. and is a rapidly growing medium in the commercial world. A particular reason for this is the growth in use of the internet as discussed below.

6. Interactive/internet marketing

Fill (2002) describes the internet as ‘a distribution channel and communications medium that enables consumers and organisations to communicate in radically different ways’. Improvements in technology have dramatically changed the nature of communications and the ways of reaching target markets. This is particularly true of younger consumers which many social marketing programmes seek to target. The use of the internet as a complementary channel to television and other media was adopted in the UK in the ‘Get Unhooked’ smoking cessation campaign.

The communications mix – a few points to note

The above classification raises a few points which it may be useful to bear in mind:

Communication tools change over time and particularly as a result of technological developments.

Related to the above point is a blurring of distinction between ‘promotion’ and ‘place’ (method of distribution). This is particularly true as direct marketing and subsequently internet/interactive marketing have been included as separate communications tools. It is also relevant to the personal selling element.

It is also notable that, in addition to target markets of final consumers, communications (in addition to other marketing mix elements) must be developed for distributors (e.g. health professionals). This is often referred to as ‘push’ promotion as opposed to the ‘pull’ promotion to the final customer.

5.3 How communications work

The paper by Kotler and Zaltman (1971) emphasises the crucial fact that, for both commercial and social marketers, it is the combination of the ‘marketing mix’ elements (i.e. product, price, place and promotion) which will effect behavioural change. So what can we expect from communication and what objectives can be set for advertising and other elements of the promotional mix? In order to answer these questions we have to have some understanding of how promotion, and specifically advertising, works.

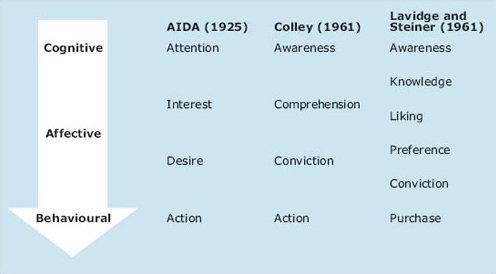

There are many advertising models and frameworks and they all have their critics. One approach is to focus on the stages which consumers move through as their attitudes towards the product develops. These are based on the attitude model which was discussed in Section 3.4, i.e. the cognitive–affective–conative model. See Figure 7.

The AIDA (attention, interest, desire, action) model was originally designed to illustrate the stages which a salesperson should take the customer through and has subsequently been adopted as an explanation of how advertising works.

The DAGMAR model (defining advertising goals for measured advertising results) provides communications tasks which are specific and measurable using a four-stage approach, i.e. awareness, comprehension, conviction and action.

Similarly, the hierarchy of effects model (awareness, knowledge, liking, preference, conviction and purchase) is based on the idea that advertising will guide potential consumers through a number of stages which are essential if purchase (or other required behaviour) is to result.

There are many criticisms of these sequential models:

behaviour can precede the other elements of attitude for some decisions.

a favourable attitude and positive intention does not necessarily result in purchase.

the length of time which consumers take to move through the stages is unclear.

how are these stages to be measured, e.g. how would you measure conviction?

similar to the general criticism of the marketing mix approach is the focus on the consumer as a passive recipient of messages rather than one who will actively engage in information search and is also likely to reject messages which are inconsistent with current attitudes.

later approaches to communication theory have added other sources of information which impact on the target market. In particular the role of opinion leaders and word-of-mouth communication from peer groups and others are important determinants of whether consumers will act on the basis of formal communications from marketers.

Although there are many issues in explaining how advertising (and other forms of communication) works and many other factors (e.g. the role of memory, the level of involvement with the product) have been included in subsequent models and examined in research studies – the sequential or stage approach can contribute to our understanding of the role of marketing communications. As with most theories and frameworks we have to ensure that the approach is relevant to the specific purpose and problem we are looking at and that we are aware of the limitations.

5.4 The role of brands and branding

Keller (2003) distinguishes between a ‘small-b brand’ as defined by the American Marketing Association:

name, term, sign, symbol or design, or a combination of them, intended to identify the goods and services of one seller or group of sellers and to differentiate them from those of competition

(Keller, 2003, p. 3)

and the industry/practitioner definition of ‘a big-B brand’. For the latter it is the amount of awareness, reputation, prominence, etc. which creates the brand. The strategic role of brands cannot be over estimated. As described above, they provide the basis for differentiation. They also enable organisations to charge a price premium and act as a barrier to market entry for potential competitors. Some of the best known and earliest brands exist in those markets in which social marketers seek to intervene and change behaviour, for example, registration of some cigarette brand names: Dunhill, 1907; Camel, 1913; Marlboro, 1924; and Philip Morris, 1933. In the fast food sector McDonalds was established in 1937 and Burger King in 1954. By contrast some of the brand names associated with social objectives are more recent, for example, Friends of the Earth in 1969 and Greenpeace in 1971.

The following figure illustrates how we, as consumers, have various levels of relationships with brands. At the base level we are interested in the product benefits. These are something which we think about and can be learned from advertising. Second, advertising can lead us to assign a personality to the brand. McDonalds is a good example. since their overt and very successful campaign led many people, and particularly children, to assign the brand personality of the cheerful Ronald McDonald to the company and its products. Finally, the consumer develops emotional bonds with the product/brand. Belch and Belch (2001) describe how McCann-Erikson (one of the world's largest advertising agencies) has adopted this approach, believing that the creation of emotional bonds through advertising is essential to a positive psychological movement towards the product/brand and will reduce the potential for switching behaviour. Such emotional bonding with McDonalds could be achieved through the association with children's parties and happy family gatherings in which McDonalds staff and products play a part.

One question for social marketers is how to use the power of branding for social aims and objectives. Additionally, to what extent is the social marketer's role to break the emotional bonds we have with organisations such as McDonalds or to build bonds with social marketing brands?

6 Course questions

Try to answer the following questions:

Question 1

What is meant by ‘social cognitive theory’?

Answer

Social cognitive theory describes how an individual's behaviour is determined by environmental factors such as family and friends, the individual's personal characteristics, perceptions of and interactions with the environment. An approach to adapting social cognitive theory to health behaviours is illustrated in Figure 1, and is also discussed in Hastings (2007), Chapter 2.

Question 2

Why is it important for social marketers to understand this?

Answer

Social cognitive theory explains how people acquire and maintain behaviours. Social marketing programmes and interventions aim to change behaviour for the achievement of social goals. An understanding of the determinants of behaviour is therefore essential for the design of effective interventions.

Question 3

What is meant by ‘moving upstream’ in social marketing?

Answer

Upstream organisations and individuals include policy makers, politicians, regulators, educators, etc. This contrasts with downstream which relates to those whose behaviour change is the goal of social marketing activity. By influencing those upstream, social marketers can help to effect legislative, policy, attitudinal and behavioural change of key actors such as medical, social and educational workers, which will ultimately impact on the focal behaviours of the end consumer.

Question 4

Effective social marketing communications require consistency of messages. Fill (2002) describes six elements which combine to produce an integrated communications programme. List the elements.

Answer

Advertising

Sales promotion

Public relations/publicity

Personal selling

Direct marketing

Interactive/internet marketing

7 Conclusion

This course aimed to answer four key questions about social marketing:

Why is a social marketing approach relevant and necessary in today's environment?

How can an understanding of consumer/human behaviour help to develop appropriate actions and interventions?

Who are the target markets for social marketing programmes?

What is the role of marketing communications and branding in achieving behavioural change?

Social marketing aims to achieve behavioural change across a wide range of issues which are crucial to the wellbeing of individuals, groups, communities and the planet. By understanding the motivations of individuals and organisations and the factors which influence this, social marketing programmes can be developed to influence and achieve behavioural change. There are many techniques and approaches which are available to the social marketer; in particular, the role of stakeholder analysis, market segmentation, marketing communications and branding have been highlighted in this course. There are many other important areas which have not been directly addressed, for example, the crucial role of research in developing insight into consumer and organisational behaviour, the social marketing planning process, the nature of relationship marketing, and the role of service organisations in the delivery of social marketing programmes.

References

Acknowledgements

The content acknowledged below is Proprietary (see terms and conditions) and is used under licence.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Course image: JD Hancock in Flickr made available under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Licence.

Case Study 11: ‘The challenges of using social marketing in India: the case of HIV/AIDS prevention’ by Sameer Deshpande (pp. 297–301) and pp. 93–98 from Hastings, G. (2007), Social marketing: why should the Devil have all the best tunes?, Oxford, Butterworth Heinemann.

Figure 1 from Hastings, G. (2007) Social Marketing: Why should the Devil have all the best tunes? Oxford, Butterworth Heinemann.

Figure 3 from Fischbacher, M. (2005) ‘Masters in public health’, course material, University of Glasgow [unpublished].

Figure 4 adapted from Johnson, G. and Scholes, K. (1999) Exploring Corporate Strategy, (5th edn), Prentice Hall Europe.

Figures 6 and 8 from Belch, G. E. and Belch, M. A. (2001) Advertising and Promotion: An Integrated Marketing Communications Perspective (5th edn), New York, McGraw.

Don't miss out:

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University - www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Copyright © 2016 The Open University