Teaching assistants: support in action

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 19 April 2024, 5:44 PM

Teaching assistants: support in action

Introduction

Teaching assistants, and similar learning support staff, are a substantial part of a workforce that spans the public sector. They are sometimes referred to as ‘paraprofessionals’ – workers who supplement and support the work of qualified professionals. We would argue, however, that teaching assistants have a distinct professionalism themselves which often overlaps with and which is comparable to that of teachers. Since first being introduced into in the 1960s as ‘aides’, ‘helpers’ and ‘auxiliaries’, teaching assistants have become essential to children’s learning in primary schools across the UK and further afield. Whatever your learning support role in schools may be, you are part of this historic development.

For convenience, we have adopted the generic term ‘teaching assistant’ throughout this free course, Teaching assistants: Support in action. We use these words in preference to ‘TAs’, which, we feel, is reducing of status. ‘Teaching assistant’ is currently the preferred term of government but there are many others in use across the UK. We therefore use ‘teaching assistant’ to refer to the various kinds of volunteer and paid adult (other than qualified teachers) who provide learning support to primary aged children in the UK.

A central feature of the teaching assistant workforce is its considerable diversity – in terms not only of titles and linked responsibilities but also of previous experience, formal qualifications, in-service training opportunities, ways of working and skills for carrying out support work. The recruitment of paid assistants and volunteers has brought into schools a range of adults in addition to qualified teachers, with much to offer children. Their work enhances children’s experience of learning in school. This course aims to reflect this diversity and to encourage you to think about your part in the many roles that teaching assistants can play.

One interesting feature of the teaching assistant workforce is the extent to which it is overwhelmingly female. Why are women, especially many who are mothers, drawn to this work, and why are there so few men? This is one of the themes you will explore in this course.

As with teachers and their work, teaching assistants require many skills for working with children, and there is often more than one way of being effective. Later in this course we examine the approach of one teaching assistant, Caroline Higham, and consider how she collaborates with a class teacher and brings her distinctive practice to a maths lesson.

Teaching assistants are a very significant and essential resource in primary classrooms, so much so that it is hard to imagine how schools could manage without them.

The Open University is conducting a survey investigating how people use the free educational content on our OpenLearn website. The aim is to provide a better free learning experience for everyone. So if you have 10 minutes to spare, we’d be delighted if you could take part and tell us what you think

Please note this will take you out of OpenLearn, we suggest you open this in a new tab by right clicking on the link and choosing ‘Open Link in new Tab’.

This course is also available in Welsh on OpenLearn Cymru.

This free course is an adapted extract from an Open University course E111 Supporting learning in primary schools

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

be able to discuss how the UK’s teaching assistant workforce came into being

be developing your understanding that teaching assistants are part of a wider assistant workforce in the public services of health, social services and education

have insights into the diverse roles and distinctive contributions of teaching assistants across the UK

be able to identify some of the skills that teaching assistants use to provide effective support and that contribute to productive teamwork

be reflecting on the value of the work of teaching assistants and on the support skills involved, and thinking about your future role.

1 The rise of assistants

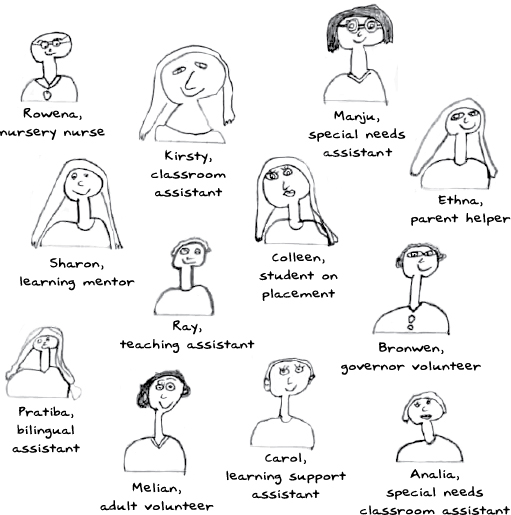

This is an image made up of twelve drawings by Emily, a six year old child, each showing the head and shoulders an adult. Underneath each adult is written their name and role within Emily’s school as follows:

Rowena, nursery nurse

Kirsty, classroom assistant

Manju, special needs assistant

Ethna, parent helper

Sharon, learning mentor

Ray, teaching assistant

Colleen, student on placement

Bronwen, governor volunteer

Pratiba, bilingual assistant

Melian, adult volunteer

Carol, learning support assistant

To gain a better understanding of the teaching assistant’s role, it is helpful to consider the ways in which different kinds of professionals are supported by assistants more widely. Just as there are teaching assistants in schools, there are equivalent roles in other areas of work. For instance, in the health service the work of nurses is supported by health care assistants, and in social work personal assistants provide support to children in care (‘looked-after children’). Ian Kessler (2002) suggests the following reasons for these developments:

- In many areas of the UK, there have been growing problems recruiting and retaining qualified professionals such as nurses and teachers.

- There has been, from successive governments, a wish to ‘modernise’ public services to make them more responsive to their ‘clients’ and more cost efficient.

- There is a belief that established professional attitudes and practices should be challenged and improved, and that professionals should develop increased flexibility in their ways of working.

As well as these overarching reasons for employing assistants, two main factors have been linked to their employment in schools. Firstly, the move towards inclusive education has resulted in the appointment of learning support assistants to give close support to children with complex learning and behaviour needs in mainstream classrooms. Secondly, the devolving of budgets to schools by local authorities and government has enabled head teachers to employ increasing numbers of teaching assistants as a cost-effective way of providing support to hard-pressed classroom teachers.

1.1 Assistant workers in other public services

The creation of a new group of assistant workers in the public services has resulted in the restructuring of traditional occupational roles and boundaries, and in professionals delegating some of their duties to others in the workplace. Health-care assistants, for instance, now assist in patient care and ward-related duties under the supervision of a registered nurse or midwife. Their duties include:

- assisting in the provision of a high standard of care to patients, promoting their equality and dignity at all times

- assisting with patient hygiene, mobility, physical comfort, eating and drinking, while observing and reporting specific changes to the registered nurse

- providing support for patients’ family and friends

- performing and reporting clinical observations of a patient’s temperature, pulse, respiration rate, and blood pressure

- obtaining measurement of a patient’s height and weight.

Before the creation of these new roles, a registered nurse carried out such responsibilities. Now, health-care assistants give support to nurses who are released to do other tasks that assume further knowledge, qualifications and skills. When looking at the duties listed above, you may have noted the generic similarities between a health-care assistant and a teaching assistant in the kind of responsibility that is given, and in the types of workplace skills that are called on. Indeed, whether or not you have first aid qualifications or medical knowledge, you may be thinking to yourself, ‘With guidance, I could do some of those duties.’ This would suggest that teaching assistants have certain transferable skills that reach across other kinds of paraprofessional work.

1.2 Supporting teachers

In England ‘workforce remodelling’ has brought about an even greater focus on the roles of the adults who work in schools, especially teaching assistants. Higher level teaching assistants (HLTAs) have taken on many of the administrative duties previously done by teachers and provide cover supervision for classes of children. Senior teaching assistants have taken on managerial roles overseeing the work of teaching assistants and students on work experience.

When we think of the teaching assistant workforce, it is also important to remember the many teaching assistants who are unpaid volunteers. Smith (2011) reported that, as of January 2010, there were 126,300 full time equivalent teaching assistants employed in local authority maintained nursery and primary schools in England. This is approximately half the number of teachers but the way in which assistants are employed, often on part-time contracts, means ‘as bodies’ they can equal the number of teachers in any one school. Local authorities do not generally keep figures for volunteer teaching assistants. Some time ago, however, a national survey of English primary, special and independent schools (LGNTO, 2000) found that each school had an average of 8.5 (includes part-time) volunteer staff. Volunteers are clearly an important, if somewhat under-acknowledged, resource in many schools, and indeed, across a wider workforce.

1.3 Professional and personal skills

Jean Ionta works as a pupil support assistant at St Patrick’s Primary School in Glasgow. ‘Pupil support assistant’ has been the preferred name for teaching assistants in Scotland. They often provide both specialist learning support and more general support to teachers. When filming the videos for this course at the school we focused on Jean as she went about her work with children and staff. We put these aspects of her work together to give a sense of her day and the professional and personal skills she brings to her role.

Activity 1 A day in the life

This is a photograph of Jean Ionta, a female pupil support assistant at St Patrick’s Primary School in Glasgow, sitting at a table in a classroom between three young children who are concentrating on writing on laminated boards with marker pens. Jean is looking specifically at the girl as she writes. The other two children are boys. On the table also are two water bottles and a pot containing pens and pencils.

As you watch the following video note in the box below how Jean goes about her work, how she describes it and how others portray her contribution. In particular, make notes on how she puts an emphasis on children’s social and personal development and her part in this. How would you describe the way she is with children and her approach to supporting learning?

There is a transcript available for this video.

Discussion

Near the very end of the video Jean states that she feels ‘the children are relaxed with me’. This is a comment that appears to point to the many relationship-making opportunities that are shown in this video. Learning support work affords the making of relationships with children, perhaps in a way that is not often possible for qualified teachers. They often need to stand back to adopt an ‘overseeing’ and leadership role for large groups of children. In their close work with children, teaching assistants can have important different teaching opportunities. We would argue that, perhaps more than teachers, assistants have openings to develop approaches that are ‘intuitive’ (Houssart, 2011) and ‘nurturing’ (Hancock, 2012).

1.4 Titles and duties

In the UK there are a number of terms in current use to describe those who provide learning support to children. It would be misleading to suggest that these terms describe the same roles and responsibilities. Rather, they relate to important role distinctions and are significant because they reflect the wide variety of work that learning support staff do.

Since the 1980s, many teaching assistants across the UK have experienced a notable change in their day-to-day involvement in schools. The concerted focus of government on literacy and numeracy has served to draw many teaching assistants into such ‘teaching-related’ duties – work that, at one time, only a qualified teacher would have done. Barbara Lee (2003, p. 27) notes the shift in terms of ‘indirect support’ (e.g. producing materials and managing resources) and ‘direct support’ (e.g. working with individual children and small groups).

Regardless of this shift in duties, tasks associated with the maintenance of the learning environment are still necessary, as they enable teaching and learning to take place. So it is relevant to ask, ‘Who does this work if assistants are spending more time helping children to learn?’ You may have some insights into this. Perhaps one answer is that there is more sharing of maintenance tasks between teachers, teaching assistants, volunteers and children.

1.5 Ways of working and contributing

The physical design of most primary schools reflects the expectation that teachers work in classrooms with large numbers of children. In fact, given their large classes, most schools feel quite crowded. The employment of teaching assistants has doubled the number of adults working in some classrooms and, as Schlapp and Davidson (2001) note, this has sometimes led to problems in teaching assistants finding work spaces they can call their own. Often they give support while working alongside teachers, but some is done in another location. In their survey of 275 teaching assistants in two English local authorities, Hancock et al. (2002) found that 91 per cent said they sometimes withdrew children from classrooms.

This is a photograph of Cindy Bhuhi, a female bilingual teaching assistant working with a group of two young boys and three young girls. All of the children are wearing aprons. In the background one of the girls is working at a worktop, on which are placed two microwave ovens and a small fridge. In the foreground is a table on top of which are a number of cooking ingredients. One of the boys is sitting at the table, and one boy and one girl are standing in front of the table looking away. Immediately behind the table Cindy appears to be helping one of the children put on her apron.

There is a further sense in which teaching assistants have needed to find ‘space’ for their work. As part of a relatively new workforce, they have had to integrate their support practice with teachers’ ongoing teaching practice and to work as part of a classroom teaching team.

Activity 2 Contexts for learning support

The following video features teaching assistants in many working contexts. The nine short clips within this video were recorded during visits to primary schools across the UK.

As you view, make notes in the box below on the roles and the contexts of these teaching assistants. If you are currently or have previously been in a learning support role, consider the extent to which your role and your various working contexts are represented by people in this sequence. Which teaching assistant roles are most like yours?

There is a transcript available for this video.

Discussion

Teachers were once expected to work in schools without the kind of support provided by the teaching assistants in this video, so it is worth considering how teaching assistants have been ‘added’ to and integrated within the primary school workforce. Staff in primary schools would no doubt argue that this is long overdue, since more adults are necessary if they are to meet children’s personal, social and educational needs. Officially, the justification for this provision has been that teaching assistants help to ‘raise standards’ in measured areas of the curriculum. Clearly, this is important, but it seems to underplay the much wider nature of their contribution. For instance, the sequence reveals the ability of all teaching assistants not only to support learning but also to interact with and relate to children in ways that enhance their self-image and experience of school life.

1.6 Growth of the teaching assistant workforce

Between the mid 1990s and 2012, in all four UK countries there was a growth in the number of teaching assistants working alongside teachers in primary classrooms. As we have indicated, the seeds of this development were sown in the 1980s, when support staff were employed to support the inclusion of children with special educational needs in mainstream classrooms. Teaching assistants were recruited to provide individualised help for children. In some areas of the UK, nursery nurses have long worked in nursery and infant classrooms where, it is felt, young children need a higher ratio of adults working with them.

The rapid growth in teaching assistant numbers that began in the early 2000s has introduced new roles, such as learning mentor, HLTA and parent support assistant. Will Swann and Roger Hancock (2003, p. 2) suggested that there had been a ‘dramatic shift in the composition of the primary classroom workforce’. To a large extent, this increase happened because funds were made available through specific government spending programmes across the UK. In particular in England there was a concerted focus on national literacy and numeracy targets in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and funds were made available to recruit teaching assistants to support the one in four children considered not to be progressing as required (Hancock and Eyres, 2004).

Volunteer and paid assistants are therefore part of a significant historical development that is having a far-reaching effect on the organisation of primary education, the experiences that children have in classrooms, and the ways in which children are taught in schools. Reporting on their large scale study, ‘The Deployment and Impact of Support Staff (DISS) project’, Blatchford et al. (2012) cite government statistics showing a threefold increase in the number of full-time equivalent teaching assistant posts in all mainstream schools in England since 1997 to a total of 170,000 in 2010.This represented 24% of the workforce in mainstream schools overall, and more specifically 32% of the workforce in mainstream nursery and primary schools. Blatchford et al. also found that by 2010 teaching assistants comprised 44% of the primary school workforce in Wales, and 24% in Scotland.

1.7 Teaching assistants in Europe

Teaching assistants and other related learning support staff are also to be found in the schools for children of British armed forces posted oversees, in the schools of other European countries and in countries such as the USA, Canada and Australia. A survey conducted by the National Union of Teachers (NUT, 1998) highlighted some interesting support roles found in European schools, and it is worthwhile to consider these in the light of the developing role of teaching assistants in the UK. As the sociologist Amitai Etzioni (1969, p. vi) believed, comparison serves to increase our ‘scope of awareness’. The NUT identified the following examples of support roles in the Netherlands, France and Belgium.

In the Netherlands, as in the UK, there have long been teaching assistants in primary schools, often working in the background and in a supportive way with young children and their teachers. Their current role is comparable with that of specialist teacher assistants in England in that they are focused on directly supporting children’s learning, particularly reading and basic skills.

In France, there are ‘surveillants’ (normally aged 18–26 years) who often intend to become teachers. Traditionally, they have contributed to the supervision of pupils when they are on the school premises and outside the classroom. They also liaise with parents in this supervisory role. More recently their role has been extended to provide support for children’s learning in classrooms. They have assumed responsibilities in the area of information and communication technology (ICT) in terms of both maintaining equipment and support for learning. There are also ‘aide-éducateurs’ (assistant teachers) who mainly take on a teaching role in direct support for learning and who facilitate extra-curricular activities.

In Belgium, there are ‘agents contractuels subventionnés’ (subsidised contract workers). They are recruited under schemes to reduce unemployment and they may become involved in childcare in pre-school settings or assist children to learn a foreign language.

1.8 Teaching assistants and The Open University

Between 1995 and 2012, The Open University trained just over 8000 teaching assistants through its course E111 Supporting learning in primary schools and its now discontinued Specialist Teacher Assistant course. Most were women and many were mothers; a very small percentage were male. Heather Wakefield (2003), head of local government liaison at UNISON, emphasises the link between caring work in the public sector and the recruitment of a predominantly female paraprofessional workforce. She suggests that a woman’s role in the household and in the family is being ‘imported’ into the workplace where it is of value in a number of ways, not least in terms of her supporting and caring abilities. Wakefield emphasises, however, that this work has traditionally been poorly paid and accorded low ‘manual’ status by employers.

The backgrounds of teaching assistants who have studied with The Open University to date provide confirmation that many have children who were educated at their school of employment, so they lived locally and were part of the wider school community. A local school is clearly a convenient workplace for a parent, as it minimises the journey between home and work. It allows those employed to work during school hours and to take time off in school holidays (though often without pay). Further, because of its focus on educating children, a school is a place where issues concerning the care of children outside school are likely to be valued and understood. Some believe that a school is a ‘family-friendly employer’, to use a current phrase. Additionally, schools are workplaces where knowledge of children and their ways is potentially of value and use. A primary school may also be seen as a community of adults and children, where a local person is likely to feel part of a continuous social network of known local acquaintances, families and familiar faces.

Activity 3 Your reasons

With the above points in mind, if you are – or would like to be – in a learning support role, make a list in the box below of your reasons for wanting to be involved in this kind of work.

Discussion

We invited Mary-Jane Bayliff, a teaching assistant who works in a Dorset School, to give an account of her reasons for working in schools. In response, she wrote:

I have always wanted to work with children. I had experience of work relating to children, for example at camps and in clubs. I felt my experience as a mother and childminder was a good foundation from which to start. I was keen to look after my own children during school holidays and during after-school hours. I had a particular interest in my own children’s school, having been a volunteer helper and member of the PTA. After seeing school through a parent’s eyes, I felt I had something of value to give, in terms of caring for children and bringing an understanding to home–school relations.

Clearly, there is much in Mary-Jane’s previous experience that contributes to her ability as a teaching assistant.

This is a photograph of Gary Fookes, a male teaching assistant crouching down in a classroom next to a boy sitting at a desk in a classroom. The boy is facing away from the camera, and Gary is positioned looking towards the boy from the boy’s left hand side.

2 Contribution and roles

Hilary Cremin et al. (2003), in their evaluation of the ways in which teachers and teaching assistants can work together in teams, suggest that, while there is enthusiasm for additional support, little attention is given to how this actually works in classrooms. It is true that learning support staff have been introduced into classrooms without clear research evidence that they can make a difference to children’s learning, but then life often moves faster than the supply of research evidence.

As we have indicated, volunteers are often invited into schools to assist teachers, and teaching assistants are employed without necessarily having any specific training (although, increasingly, in-service training is being made available). However, as we have suggested, volunteers and teaching assistants often have relevant informal experience, transferable abilities and intuitive skills that can support the work they do in schools. Furthermore, common sense suggests that, when large classes of children have access to additional adults who wish to help and support them, this will have a favourable impact on their learning and development. For instance, in a similar way, many schools actively encourage parental involvement in children’s homework.

2.1 What is the value of teaching assistants?

Over time, evidence of the value of teaching assistants has increased, particularly in research reports. Kathy Hall and Wendy Nuttall (1999) in their survey of English infant teachers found that 75 per cent rated classroom assistants as equal to, or more important than, class size in terms of the quality of teaching and learning. Valerie Wilson et al. (2002) provided evidence from Scotland and Roger Hancock et al. (2002) added to the evidence from England. References to the important work of learning support staff can also be found in formal inspection reports from the national inspection bodies. In Northern Ireland a chief inspector’s report stated, ‘Evidence from inspection highlights the positive contribution made by classroom assistants, including those employed under the “Making a Good Start” initiative (MAGS), in helping to promote and support the children’s early learning and development’ (ETI, 2002).

The large scale study by Blatchford et al. (2012) examined two aspects of impact:

- the effects on teachers in terms of their workloads, job satisfaction and levels of stress, and their teaching

- the effects on pupils, in terms of their learning and behaviour, measures of positive approaches to learning and their academic progress in English, mathematics and science.

As might be expected given other research studies to date, the researchers found that assistants had positive effects on teachers and their teaching. Surprisingly, however, they found ‘a negative relationship’ between teaching assistant support and pupils’ measured academic progress. They state, contrary to common sense, it seems, ‘The more [teaching assistant] support pupils received, the less progress they made.’ (Blatchford et al., 2012, p. 46). We find this hard to believe.

The authors do not attribute blame to teaching assistants, however. They explain this finding by pointing to factors governing assistants’ working contexts, the general lack of briefing that they receive, and the need for teachers to share their own higher order skills and knowledge. Nevertheless, our association with teaching assistants and their work over a long period suggests that the reality is far more complex.

2.2 Children’s and parents’ views

What do children and parents think of teaching assistants? Curiously, little has been written about their perspectives. A small-scale study involving 78 primary-aged children in England (Eyres et al., 2004) showed that children can, when asked, differentiate between their own class teacher and other adults who work with them. However, the children reported a substantial overlap between the activities of teachers and teaching assistants. For instance, eight-year-old Sarah said:

Well, the helpers seem to help out and do what the teacher does and the teacher seems to mostly teach children. But sometimes the helpers teach children.

Eleven-year-old Lissette speculated:

Well, Miss McAngel is the actual teacher, teacher, teacher. She actually teaches us everything because she’s just a teacher and she teaches us everything. But, if you like, you’ve got another teacher, they teach us – pretty much they’d teach us everything but Miss McAngel would do different things with us – d’you know what I mean? – sort of, I can’t put it into words really – but – can you help? (looking towards Tim, her friend).

This is a child’s drawing showing five people, arranged in two rows. In the top row from left to right are a person with short hair and wearing glasses, and two slightly shorter people with curly hair. In the bottom row from left to right are a lady who appears to be wearing a sari and with her hair in a bunch to one side of her head, and an unfinished drawing of a person with long hair.

To a large extent, teachers and teaching assistants were seen by the children in this study as working in ‘interdependent’ ways, with each making a significant contribution to children’s learning.

With regard to parents, given that many teaching assistants are parents from the local community, we can speculate that other parents are in touch with the ways in which teachers have increasingly delegated certain teaching-related responsibilities to assistants. But maybe this is not the case. Teaching assistants, after all, are a new workforce. When today’s parents were at primary school, they would not have had experience of assistants working alongside teachers in the way that children do now.

A questionnaire survey of parents’ perceptions of assistants by two specialist teacher assistants working at Roche CommunitySchool in Cornwall (Strongman and Mansfield, 2004) found that most of the parents placed great value on the contribution of teaching assistants. As one parent wrote, ‘They are of value as a backup for the teacher, as an extra pair of eyes in the classroom.’ Another parent noted, ‘A good assistant can be priceless in the classroom. With up to thirty-seven children in each class, how could a teacher do her job effectively without assistants?’

However, while these parents recognised the important role of assistants in their children’s primary school, many also felt that there should be a clear distinction between the roles of teachers and teaching assistants. As one parent said, ‘Teaching assistants should not “teach” the class, they should only assist the teacher.’ The extent to which this linguistic distinction – between ‘teaching’ and ‘assisting’ – can be maintained in classrooms when many teachers and teaching assistants are now working closely together in teams is open to question. When a teaching assistant ‘assists’ or ‘supports’ or ‘helps’ a child, there is always the possibility that the child will learn. Therefore, it could be said that the assistant has ‘taught’ that child, just as it could be said that parents teach their children many things and children often teach each other.

Perhaps a more appropriate way of thinking about this is to say that teachers, as qualified professionals, hold the overall responsibility for what goes on in a classroom in terms of learning and teaching. Children, it seems, understand this. In the study by Eyres et al. (2004) a number of children were clear that the teachers in their classrooms were ultimately in charge. As six-year-old Sam commented:

Well, Mrs Wilson and Mrs Georgio [both teaching assistants] don’t tell us what to do. Mrs Watts [the teacher] tells us what to do.

2.3 Distinctive contributions

In Activity 1 you looked at the various support roles of Jean, a pupil support assistant. Let us now consider the essential nature of the work that assistants do and the way they contribute to the totality of work in a classroom.

Are teaching assistants ‘simply’ assisting teachers in doing their work? If this is so, it seems that teachers and assistants are working together to carry out the duties that previously teachers working alone would have covered. On this analysis, teaching assistants take on those whole-school and classroom duties that teachers feel they can delegate to a less qualified, but not necessarily less experienced, colleague. In theory, this should leave teachers with ‘spare’ time to do additional tasks of their choice, because another person is doing part of their work. Alternatively, perhaps teaching assistants are in part doing tasks that teachers do not have time to do themselves. If this is so, then the job of teaching a class has ‘expanded’, since both teachers and teaching assistants are still finding more than enough work to do.

Job descriptions aim to capture the work that teaching assistants should do. This might be categorised in terms of ‘administrative duties’, ‘classroom resource preparation’ and ‘work with children’. An interesting framework for thinking about roles, duties and the focus of support work was provided by the DfEE (2000, para. 2.5), which suggested four levels of support for:

- pupils

- the teacher

- the school

- the curriculum.

You will consider the usefulness of this framework in the next activity.

Activity 4 Roles and responsibilities

Now read Reading 1, ‘Ten titles and roles’ by Roger Hancock and Jennifer Colloby (2013). It contains thumbnail sketches of the roles and responsibilities of ten learning support staff.

Select one sketch that particularly interests you and consider the extent to which the title and role described relate to the DfEE’s four-part framework. Does the framework capture the totality of your working week or, if you do not currently work in learning support, your perception of the working week of a teaching assistant?

Discussion

A factor that we have not yet mentioned but that impacts on the ways in which teaching assistants are deployed is their flexibility as a workforce. Many are employed on a part-time basis, often with short-term contracts. One classroom assistant told us, ‘My job description changes every term!’ Teaching assistants may be moved around in a school so that they can work with individuals and groups of children as and when the need arises. As you may know, in England the national literacy and numeracy strategies introduced a large number of ‘catch-up’ and ‘booster’ programmes for children who are not meeting expectations. Teaching assistants have been very much involved in these programmes, which require considerable flexibility on their part as they work across year groups with identified children.

2.4 The evolving role of the teacher

The impact of the expanding contribution of teaching assistants on the teacher’s role is generally recognised as being positive. It is worth acknowledging, however, that many teachers have had to make adjustments to their practice in order to work with teaching assistants as team colleagues. Many are able to make this adjustment. We do sometimes, however, hear of teachers who find it hard to work well with another adult in a classroom context. Despite the presence of assistants in primary schools, the focus of much initial teacher training still tends to focus on teachers working in classrooms on their own rather than as collaborators with other adults. Teachers who have only recently achieved qualified teacher status (QTS) may therefore need time to establish how they wish to approach teamwork and, what is essentially, team teaching.

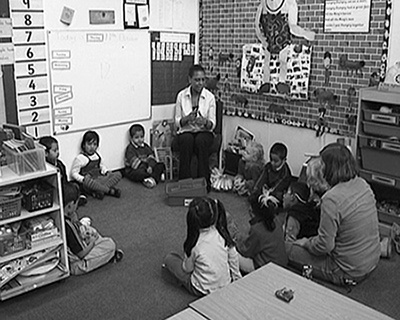

This is a photograph of a female teacher sitting on a chair in the corner of a classroom talking to a group of ten young children sitting on the floor in a circular arrangement in front of her. Another female adult is sitting directly behind two of the children. A number of displays are on the wall behind the teacher, including numbers, words and a large collage of humpty dumpty sitting on a wall.

Most, if not all, would agree that teaching assistants bring considerable benefits for teachers and children and to school life more widely. However, while there is talk of teaching assistants reducing teachers’ workloads, the reality is not so straightforward. If teachers are to benefit from the expertise that a well-informed teaching assistant can bring to the partnership, they need to find time to discuss and share ideas on teaching and the curriculum. This is not unlike the role that teachers take on in their supervision of students on teaching practice, where co-planning, co-teaching and feedback form much of the early stages of their training.

We often read that assistants ‘work under the close supervision of teachers’ or that teachers ‘manage’ teaching assistants. This is a time-consuming role, which encroaches greatly on the teaching and non-teaching time of teachers. Furthermore, teachers are legally required to take responsibility for teaching assistants’ day-to-day interactions with children and to oversee their support work. Unlike teachers, assistants cannot be in loco parentis (literally, ‘in the place of a parent’) and so cannot take the responsibility that the law requires of teachers when children are in their care. This means that teaching assistants must be guided and supported by teachers, not only in terms of their curriculum-support practice but also in key areas of work such as health and safety and child protection.

The great majority of teachers recognise the part that this extra work plays in the provision of a future teaching force; moreover, they appreciate that sharing good practice and observing colleagues can help them to develop their own role. Given the limited amount of non-contact time in primary schools, teaching assistants and teachers are required to manage carefully the little time they have available for productive discussion.

3 Support in action

A teaching assistant’s role of supporting teaching and learning in the classroom may evolve with time. Alternatively an assistant may be recruited to the role for that very purpose, or perhaps they might lie somewhere in the middle, having joined the body of teaching assistants just as the role was being reviewed and bearing witness to its expansion and development. In the penultimate section of this course, we focus with a degree of detail on the practice of teaching assistant Caroline Higham.

3.1 Focusing on practice

This is a photograph of Caroline Higham against a plain background. She is wearing a v-neck top, has shoulder length hair and is smiling.

Caroline Higham is relatively new to the role of full-time teaching assistant. She has two children who were educated at the school where she is employed. Caroline would eventually like to be a qualified teacher and she is studying to complete a relevant degree on a part-time basis.

Over the few years that Caroline has been at the school, her role has grown both in the number of hours that she works and in the nature of her responsibilities. She now has considerable responsibility for organising and maintaining the school’s reading programme and she works closely with the head teacher, who is responsible for this area of the curriculum. Caroline is involved in the refitting of the school’s library and the purchase of new library books. She enjoys her associated responsibility for children’s progress and attainment. She keeps records of the individual children she supports, and she updates these at the end of each school day and shares them with staff.

Caroline has gained many insights into individual children’s learning and the barriers to learning that they might experience. Parents often ask her for advice, so she has to judge when to pass their requests to teaching staff. In her own area in the school, where she sometimes works with small groups of children or with individuals, the atmosphere is welcoming and there are stimulating displays on the walls.

Activity 5 Providing support

Read Reading 2, ‘Support in a mathematics lesson’ by Jennifer Colloby (2013).

When you have read the extract, look at the following list of three HLTA standards:

- 3. Demonstrate the positive values, attitudes and behaviour they expect from children and young people

- 14. Understand the objectives, content and intended outcomes for the learning activities in which they are involved

- 22. Monitor learners’ responses to activities and modify the approach accordingly

Note in the box below the ways in which you think Caroline exemplifies the three selected standards.

Discussion

Table 1 shows what we thought.

| HLTA standard | Caroline’s practice |

|---|---|

| 3. Demonstrate the positive values, attitudes and behaviour they expect from children and young people | The way in which Caroline goes about her support role suggests that she has the skills to keep children on task when necessary, to confirm their achievements, and to ensure that her group is engaging with the planned activities. |

| 14. Understand the objectives, content and intended outcomes for the learning activities in which they are involved | She displays a sense of purpose about the lesson through her interactions with and directions to children. This is revealed in her knowledge of the purpose of the lesson and her awareness of the tasks that children need to complete. |

| 22. Monitor learners’ responses to activities and modify the approach accordingly | At all times Caroline shows a good awareness of what each member of her group is doing. She makes adjustments to her interactions and support based on the children’s changing needs. |

Standards – whether national occupational standards for teaching assistants, HLTA standards, or those related to the award of QTS – often contain several ideas and practices. For instance, HLTA Standard 14 above contains three ideas with regard to lessons. When standards are matched to practice, judgements must be made about whether certain examples of practice qualify for a full or partial claim and how much evidence of successful practice is required for a standard to be met. From the description of Caroline’s practice in the extract, it seems that she could claim competence in the three standards listed in the table.

3.2 Assisting, supporting and teaching

The idea that teaching assistants ‘assist’ teachers and ‘support’ learning has been the official view of a teaching assistant’s role for a long time and many policy makers continue to regard their work in this way. Suggesting that teaching assistants teach children has been taboo but this appears to be changing. In England and Wales HLTAs were originally meant to ‘cover’ lessons that were previously planned lessons by teachers but there is reason to think that many are teaching, not least because covering invariably involves interaction with children and that potentially moves an adult into a teaching relationship (Hancock et al., 2010; Sendorek, 2009). The Open University’s Foundation Degree for teaching assistants is clear about being a degree in primary ‘teaching and learning’ rather than a degree ‘in supporting learning’, for example. Dillow (2010, p. 8) suggests that teaching assistants are involved in jobs that ‘look like teaching’, as well as in more traditional assisting tasks. Blatchford et al. (2012) state that if teaching assistants have a ‘direct pedagogical, instructional relationship with pupils’ (p. 140) they are to all intents teaching.

Although, in theory, ‘assisting’ marks out a conceptual distinction between teachers and assistants, in practice this is very difficult to maintain. This is because the effect of what adults do with children in schools is, to a considerable degree, determined by children’s reactions to the adults who work with them. Teaching is not something that can be done ‘to’ children. In order to be successful, it is an act that needs their involvement – something that is done ‘with’ them. Children are therefore always agents in the teaching enterprise because they have influence over whether or not teaching happens. It therefore follows that a teaching assistant could conceivably, from a child’s perspective, teach more effectively than a teacher. Eyres et al. (2004) note this in a study of how children perceive the difference between teachers and teaching assistants.

4 Looking to the future

It would be a brave person who tries to predict the future in any area of work. However, in gathering resources for this course we have been in a position to obtain a good sense of how teaching assistants are currently working in primary schools across the UK. We are also in touch with a large number of assistants studying courses with The Open University and note how they write about their day-to-day work. This provides us with an idea of how the role is developing and also how it might possibly develop in the future.

Doubtless, since The Open University first launched a specific advanced qualification for teaching assistants in 1995 (The Specialist Teacher Assistant Certificate), assistants have, increasingly, become involved in the work that teachers do. We would include here the following traditional teacher tasks:

- planning for children’s learning

- teaching lessons

- evaluating and assessing learning

- teaching whole classes

- liaising with parents about children and their learning

- managing and appraising staff.

Of course, not all teaching assistants do all of these things. Some do some of them as well as other kinds of schoolwork such as the preparation of learning resources, playtime supervision, running after-school clubs and collating school records. Such is the extensive range of tasks that assistants perform, some teaching assistants may feel that they don’t, as yet, do any of the items listed but that they are still deployed in other important ways in their school. Some teaching assistants, however, do all six of the duties listed, especially long-serving and senior teaching assistants.

At the time of writing this course, the extent of teaching assistant involvement in qualified teachers’ work seems to us to be quite considerable. This can be regarded as a steady, albeit quietly implemented, development over time. It has mainly happened since the mid 1990s but many teaching assistants before then were (in fact, if not officially) taking on teaching responsibilities, especially those working with children deemed to have special educational needs.

What seems to be emerging, in schools where staff deployment is approached in a highly creative way, are new teaching assistant roles that can be linked to:

- staff management responsibilities

- qualification specialisms that teaching assistants can sometimes bring to their roles

- teaching assistant enthusiasms, and thus knowledge, in a specific area of the curriculum.

In all three areas teaching assistants are taking on responsibilities that qualified teachers might do.

Conclusion

One of the central aims of this course has been to give you a sense of how teaching assistants are part of an exciting educational development. We have therefore set the employment of teaching assistants in the context of the widespread growth of a new paraprofessional workforce across public services. We have noted the gendered nature of this workforce in schools, identified reasons why local parents in particular are attracted to working in schools, and highlighted the valuable contribution that teaching assistants make in view of their life and previous work experiences. We have suggested that, although there is much overlap in the roles that assistants perform (whatever their title and wherever they work in the UK), there are also important defining distinctions to be made. Teaching assistants take on a wide variety of responsibilities. The overlap between the roles of teachers and teaching assistants continues to increase over time and the distinctive contribution that teaching assistants make in their own right has become more creatively defined. We can expect that these role and workforce developments will continue to change given the way successive governments introduce new policy and practice changes in primary education.

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course E111 Supporting learning in primary schools..

References

Acknowledgements

This free course is an adapted extract from the course E111 Supporting learning in prrimary schools, which is currently out of presentation

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Course image ©MyFuture.com

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

This free course is an adapted extract from the course E111 Supporting learning in primary schools which is currently out of presentation.

Don't miss out:

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University - www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Copyright © 2016 The Open University