Robert Owen and New Lanark

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 25 April 2024, 1:53 AM

Robert Owen and New Lanark

Introduction

Robert Owen (1771–1858) (see Figure 1) was one of the most important and controversial figures of his generation. He lived through the ages of Enlightenment and Romanticism and was personally touched by the ideas and dramatic changes that characterised that era. Profiting enormously during the first half of his life from the progress of industry and having the financial means, he later devoted himself to publicising and practising his social and economic ideas. Most of these derived from Enlightenment notions and, he thought, could eliminate poverty and crime, contributing to social and moral betterment.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of Level 2 study in Arts and Humanities.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

understand the Enlightenment ideas that underpinned Robert Owen's social reform agenda

understand how Owen's background and experience at New Lanark fed through into his thinking in the essays in A New View of Society

understand the main proposals in the essays

understand New Lanark's role as a model for social reform during this period.

1 A New View of Society

Some of Robert Owen's ideas were confirmed by personal experience as a philanthropic employer who strongly emphasised the importance of environment, education and, ultimately, cooperation in improving social conditions. Owen was closely involved with the factory movement (for the improvement of working conditions), Poor Law reform, public education, economic regeneration in post-Napoleonic War Britain, the relief of distress in Ireland, creating what he called ‘communities of equality’ in Britain and America, and, after 1830, trade unionism and cooperation. He supported religious toleration. He advocated sexual equality, marriage and divorce law reform, and alluded to birth control as a means of regulating population. He thus gained fame, even notoriety, as a social and educational reformer, and long after his death continued to inspire others, notably through the ideas presented in his most important and famous work, the essays in A New View of Society.

A New View of Society is an important text for three reasons. First, it is a brilliant illustration of the notion that there are general, universally applicable rules or principles that we can discover through proper, empirical, use of reason, and which once identified will lead to progress (economic, social) and greater happiness. Apart from the ideals of social progress through the means of reason, and happiness generated by rational means, the essays highlight other key Enlightenment notions too. These include reference to the view that human nature is universal, the use of reason to dispel error and darkness from the human mind, the attack on superstition, the appeal to ‘nature’ and the natural environment, the importance of self-knowledge, and the reasoned conditioning of people.

Second, it highlights important aspects of economic progress and political and social change in Britain during and after the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. It shows how enlightened ideas could be applied to reform issues, particularly the major social problems of the period: poverty, poor housing, diet and health, and lack of educational opportunity. Owen's brand of rationality and progress may well have been deployed to his own pragmatic, commercial ends, but there is more emphasis on the happiness of the lower orders than in most Enlightenment texts.

Third, while it shows how Owen's ideas relate to wider currents of thought and the problems of his day, A New View of Society also serves to emphasise the point that Enlightenment and Romanticism did not necessarily progress neatly and steadily. Owen clearly held, well into the nineteenth century when Romantic ideas were making strong headway, many enlightened notions from the second half of the eighteenth century. Ideas and intellectual movements invariably overlapped.

Although the essays were all written at slightly different times between 1812 and 1814, they have a coherence arising from the subject matter. In turn they explain Owen's views about character formation, how his theories were applied in the context of New Lanark, the potential for further reform and, finally, the application of these ideas nationally and internationally.

Owen was often portrayed as benevolent and kind, a defender of factory children and a patron of the poor, all of which paint an essentially accurate picture of the man. But he also attracted considerable criticism, being described by his detractors as a knave, a charlatan and a speculative, scheming, mischievous individual. He had enormous wealth, much of it spent on his propaganda campaigns and, it has to be admitted, on self-promotion. Yet he disclaimed any self-interest. He had considerable charisma, which won him large audiences, including apparently many women. His flirtations with royal dukes and cabinet ministers made him enemies, particularly among political reformers, who ought to have been his natural allies. Owen evidently believed, however, that he was being propelled by some supernatural force to change society. Perhaps blinded by the strength of this conviction he was utterly single-minded in advocating his views, which, he felt, held the solution to the problems of his time.

Yet I am sure you will enjoy the modernity of Owen's practical measures, from nursery care to pension funds, even if his ‘principles’ are not always immediately evident. Although I shall guide you through the extracts in the essays, you might like to read them over now to get a sense of their style and content. You may also like to take a preliminary look at the video New Lanark: A New Moral World? (given below in three parts), to which you will be referred later in this course. The essays are provided as links below the video clips.

Click play to view the video (Part 1, 11 minutes)

Transcript: New Lanark: A New Moral World? - Part 1

Click play to view the video (Part 2, 11 minutes)

Transcript: New Lanark: A New Moral World? - Part 2

Click play to view the video (Part 3, 10 minutes)

Transcript: New Lanark: A New Moral World? - Part 3

Click document below to open the First Essay

Robert Owen, A New View of Society

Click document below to open the Second Essay

Robert Owen, A New View of Society

Click document below to open the Third Essay

Robert Owen, A New View of Society

Click document below to open the Fourth Essay

Robert Owen, A New View of Society

Before undertaking a closer reading of the essays, let us look at the economic and political situation at the time they were written and say something about Owen's origins and career, as well as the background to the essays.

2 Progress and the economy

2.1 The cotton industry

Owen personified one of the key Enlightenment notions of belief in progress. Economic progress, as anticipated by Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations (1776), arose partly from industrialisation. Britain was the first country to experience an ‘Industrial Revolution’, which was at its most dynamic during our period. It gradually transformed production from small-scale, craft-based activity to mass manufacture. While many economic activities were subsequently affected, it was in the textile industry, notably cotton spinning, that the ‘factory system’ was first shaped. Cotton fabric was then in great demand because of its lightness, the fact that it could be printed with fashionable patterns and it was easily washed. The potential for its mass manufacture was unlocked by a series of innovations in spinning machinery, notably the water-frame and the mule, driven by waterpower or steam-engines in specially designed factories.

Owen, first as a spinning machinery builder and later as a cotton spinner in Manchester, in Cheshire and at New Lanark, was familiar with this equipment on a daily basis. Indeed, his technical expertise undoubtedly contributed to his success as a businessman, and possibly also gave him deeper insights into how a workforce could be deployed to improve efficiency and raise productivity on the factory floor.

A significant link to another part of this course lies in the fact that the raw material at the centre of this revolution was produced by slave labour in the plantations of the West Indies and more extensively in the southern American colonies, by then part of the United States. Most raw cotton was imported from source to the ports of Liverpool and Glasgow, cities with hinterlands where textile skills had long been established in either linen or fustian (a coarse cotton fabric) manufacture. Indeed, by the late 1780s, when Owen, still in his teens, migrated there, Manchester had become the commercial centre of the cotton industry in northern England, while Glasgow performed a similar function for the Scottish Lowlands. The Lowlands, like upland Lancashire and the West Riding of Yorkshire, had copious supplies of waterpower which could be harnessed as the prime mover of early industrialisation, notably on the river Clyde 25 miles south of Glasgow. It was there near the old town of Lanark that New Lanark was built (Donnachie and Hewitt, 1999, pp. 17–34).

2.2 David Dale and New Lanark 1785–1800

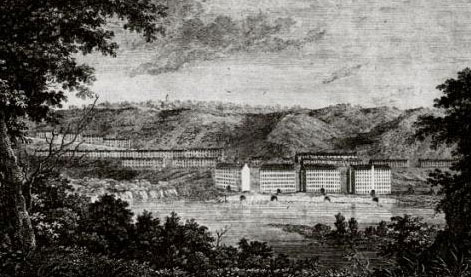

Although New Lanark was not the first, it became one of the largest and most important cotton mills of its period. It was planned and developed near the Falls of Clyde in 1785 by David Dale (1739–1806) (see Figure 2), a prominent Glasgow merchant banker, and by Richard Arkwright (1732–92), who in the 1780s was actively promoting his patented water-frame both in Scotland and on the Continent. Arkwright soon abandoned his interest, leaving Dale and his managers to build New Lanark on a site feued (leased) from Lord Braxfield (1722–99), who had an estate nearby. (Incidentally, Braxfield, as Lord Justice Clerk, presided in 1793 at the trials of the leading Scottish Friends of the People, a group that advocated moderate parliamentary reform as a means of preserving the British constitution, including the Radical lawyer and great Scottish patriot Thomas Muir (1765–99).) The large mills, four in all, were constructed by the river's edge, and water to drive a series of massive wheels was diverted from the Clyde by tunnel and aqueduct. Beyond the mill complex Dale created a model industrial community with a planned village providing housing, school, kirk (or church) and other social facilities for its workers. What all this cost is unknown, but when Owen and his partners bought the place in 1799 they paid £60 000, said to be cheap at the price. So Dale's investment was substantial, making New Lanark one of the largest plants of its kind.

Exercise 1

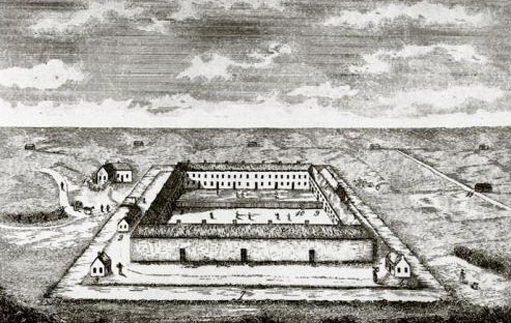

Examine Figure 3 above, the earliest representation of New Lanark, then view the introductory section of the video given below. Describe the location and layout of the mills and community.

Click play to view the introduction section of the video (Part 1, 11 minutes)

Transcript: Introduction - Part 1

Click play to view the introduction section of the video (Part 2, 11 minutes)

Transcript: Introduction - Part 2

Discussion

The mills are by the edge of the Clyde at a point where the head of water was at its optimum for driving the machinery. The mill races from four of the wheels can be seen in the engraving. Because of the constricted nature of the site the housing is ranged behind, some stretching uphill to the left and some (the earliest, we think) beyond the mills to the right.

Apart from the costly technical and engineering difficulties involved in such a massive project, assembling a large and suitable labour force (initially perhaps comprising 1000 people) was a difficulty that Dale (and later Owen) shared with many other mill owners. Locals, perhaps understandably, seemed reluctant to seek employment for long hours in a place whose barrack-like appearance resembled a workhouse, and more widely people were said to be ‘averse to indoor labour’, meaning they did not seem to like the idea of working in ‘manufactories’, as they were called. Accordingly large families were recruited from other parts of Scotland and, as was the norm, both women and children were employed. In truth a large proportion of the labour force (maybe as much as half) were children, some being orphans apprenticed from the institutions or parishes of Glasgow and Edinburgh. The men worked as tradesmen or overseers, or, if they lacked skills, as labourers. There was also a distinctive and substantial cohort of Gaelic-speaking migrants from the Scottish Highlands, some of whom Dale had rescued from a storm-bound emigrant ship bound for North America, and others he had enticed to New Lanark from localities as far apart as Argyll or Caithness by offers of employment and housing.

By the early 1790s New Lanark, deep in its valley by the Clyde, had a densely packed population of about 2000, half of whom were either children or teenagers, the majority employed in the mills. Apart from assembling and training the labour force, the maintenance of time-discipline in the works and of order in the community must have presented major problems. Although an astute businessman, Dale was also a pious individual, head of a Dissenting Presbyterian sect, and his regime was reported as paternalist. By the standards of the time he and his resident managers provided decent working conditions and seem to have been particularly attentive to the accommodation, clothing, health and diet of the child apprentices (Donnachie and Hewitt, 1999, pp. 40–9).

Whoever inherited the community Dale had established would have a sound foundation on which to build, quite apart from the success of the business, by modern values probably a multimillion pound enterprise even before Owen and his Manchester partners assumed management. We shall learn more about the early history of New Lanark and view other features on the video later in the course. But for the moment this brief description of New Lanark highlights some of the major difficulties of industrialisation and the social problems the economic transformation engendered.

Exercise 2

Review the preceding section and identify some of the key problems that industrialisation seemed to generate.

Discussion

There were major architectural and engineering problems in building the new factories, but these were soluble with large amounts of capital investment (on which, with good management and luck, substantial returns were possible). Perhaps more acute were the difficulties of assembling, retaining and controlling a large labour force. This often involved in-migration to new localities, over quite long distances and from different linguistic, cultural and religious backgrounds (likely to generate tension in the new communities). Housing had to be constructed very quickly. High densities, rudimentary water supply and poor sanitation threatened health and promoted disease. Factory masters were also concerned about preventing immorality, drunkenness and crime among workers.

I would not have expected you to get all of this, or necessarily to put it all in the same order, but you can see that the growth of New Lanark and other factory communities brought many of the social changes – and problems – that accompanied industrialisation generally. There were already major concerns about a whole host of issues, including population growth, urbanisation, health and disease, crime and policing, children's employment, adult unemployment, poverty and popular education.

Anyone with the answers to these problems was certain to command attention from governments wrestling with the costs of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. These conflicts hit the pockets of the landowners and industrialists through taxation, even though some were profiting handsomely from improved agriculture and the new manufacturing. There were also worries, widespread among the middle and upper classes, about increasing poverty and social unrest. And, as with slavery, many if not all of these issues challenged the enlightened and humane, who believed in social progress.

3 Politics: Radicalism and reaction

Although ambiguous in his political views, Robert Owen could hardly avoid politics. As we shall see, he assiduously cultivated politicians or anyone else in authority who might be persuaded to support his plans for social reform.

The political background to Owen's essays is extremely important and complex, but on the international front the key features were undoubtedly the ideas underpinning the French Revolution, and the subsequent French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, which had considerable impact on the domestic politics of the major European powers, including Britain.

Exercise 3

Consider the major historical events of the period roughly spanning 1795–1815. What key events or movements do you know of on (a) the international front and (b) the domestic scene that might form the political background to Owen's ideas?

Discussion

You might have been able to pick out the major developments and dates around which the following more detailed responses to (a) and (b) are constructed.

The major items internationally, apart from the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, were the introduction of Napoleon's Continental System (1806) and the War of 1812 with the United States (1812–15). Domestically, the Industrial Revolution proceeded apace, but economic progress was accompanied by widespread social and political protest, the latter partially inspired by Jacobin and French revolutionary ideas.

The fall-out from the French Revolution touched many parts of Europe and sucked all the major powers into long-term conflict lasting, with several short spells of peace, from 1793 to 1815. Britain was involved throughout, with one brief break (of a year) during the peace of Amiens, 1802. The expansionist aims carried the Revolution well beyond the frontiers of France – to the Netherlands, for example – but subsequently, as you have seen, Napoleon as consul and then as emperor set out to conquer much of the Continent. The fight back was led by Britain, Prussia, Austria and Russia, in what became by the 1800s virtually a global war. By the time Owen was writing the First Essay Britain was also drawn into direct conflict with the United States in the War of 1812, which jeopardised the economy, trade and, specifically, the cotton industry as long as it continued. However, as Owen himself demonstrated by judicious management at New Lanark, raw materials could still be obtained from alternative sources, for example in the West Indies, and new markets could be profitably exploited in the Baltic and Russia. Napoleon's earlier Continental blockade (1806–9) did temporarily reduce Britain's exports to Europe, though Owen seems to have maintained his Russian markets. Indeed, Russia's reluctance to enforce the Continental System was one cause of Napoleon's invasion of that country. High demand for military supplies and in the domestic market meant that industry and agriculture generally expanded rapidly during much of the war.

Britain was unusual among the great European powers because it was a constitutional monarchy with representational government in the House of Commons, albeit on a very limited franchise, mainly controlled by landowners. The governments of the time had to face not only the wars but increasing domestic problems. These included the Irish Rising (1798), the activities of Radicals advocating political reform (but rarely revolution on French lines), and waves of industrial unrest provoked by organised labour, including the Luddites (who, in protest against the mechanisation that was costing them jobs, broke into mills and wrecked machinery), at their most active in 1812–13. Protest was thus partly economic. The economy expanded rapidly during the war, but even before its conclusion there was a decline in trade, creating unemployment and social distress. These in turn exacerbated the growing problem of the poor, whose numbers were rising due to the economic turmoil in countryside and town.

Suppression was the government's first response to protest, and this found expression in the raising of local militia, censorship or gagging of the press, vigorous prosecution of troublemakers, forcing the Radicals and other political associations underground, and establishing an espionage network to monitor all anti-government activities. The government also passed a raft of legislation against organised labour including the Combination Acts (1799, 1800), designed to outlaw trade unions and at the same time prevent the emigration of skilled labour, particularly to the United States. So despite long-term success in the wars and rapid progress in the economy, the authorities faced enormous problems. Worse was to come in the post-war depression, which lasted until 1820.

We shall refer in greater detail to the events and political personalities of 1812, the year Owen started work on the essays, in due course. But for now we turn our attention to Owen's background and early career in order to identify major influences on his ideas.

4 The making of a social reformer

4.1 Environment and education: Wales 1771–c.1782

Owen had a remarkable career even before he reached New Lanark. His kin and upbringing at Newtown in mid-Wales were highly influential. His parents were shopkeepers and his father was also the postmaster and a churchwarden. So the Owens possessed practical retailing and administrative skills, which they passed on to their offspring, including Robert, a precocious and clever boy. Newtown was located in one of the most profoundly rural parts of southern Britain, yet beginning to be touched by economic change radiating out from Shropshire to the east and Cheshire and Lancashire to the north. Set in the beautiful surroundings of the upper Severn valley, it was a small market town with a woollen industry and other crafts, a role model for a self-contained community of its time. People were highly religious and the Owens were no exception, though they seem to have adhered to Anglicanism rather than embracing Methodism, which had made a big impact (and caused sectarian bitterness) throughout this part of Wales. Newtown was also at something of a linguistic and cultural divide, a bilingual town surrounded by a Welsh-speaking hinterland. Owen was probably bilingual and later deployed his Welsh eloquence to good effect in writing and on public platforms. He evidently made such good progress at school that when he was eight or nine years old the master made him his ‘assistant and usher’ in return for free education for the rest of his schooling.

Robert seems to have played the role of monitor, created in early nineteenth-century schools modelling themselves on the ideas of educational reformers like the Quaker, Joseph Lancaster (1778–1838), and the Scot, Dr Andrew Bell (1753–1832), later adopted by Owen himself in the schools at New Lanark. This was mass production applied to education, where specially selected senior pupils passed on learning by rote to their juniors, sometimes in large numbers, in what became known in France as ‘mutual instruction’. So Robert ‘acquired the habit of teaching others what [he] knew’ (Owen, 1971, p. 3), and this experience probably gave him early responsibilities for the care, supervision and education of others. He also gained some knowledge of the elementary school curriculum, which he would revisit in his later career.

At the same time his education was carried beyond the schoolroom. ‘At this period’, he says, ‘I was fond of and had a strong passion for reading everything which fell in my way’, and his family's position in the community opened up to him the libraries of the learned – the clergyman, doctor and lawyer – ‘with permission to take home any volume’ that he liked. His reading matter, as a result, included many classics like The Pilgrim's Progress, Robinson Crusoe and accounts of Captain Cook's voyages (Owen, 1971, p. 3).

Robert apparently believed every word in the books to be true, which in the examples of The Pilgrim's Progress and Robinson Crusoe may have proved significant in shaping his views about religion and enterprise. Certainly as an adult he identified closely with the famous shipwrecked hero cast up on his desert island. Robinson Crusoe, of course, was more than just a romantic adventure likely to capture young Robert's imagination, for it was also a highly moral tale, with strong religious, environmental and economic messages. ‘We do not read it’, the literary scholar Angus Ross has observed,

only in order to escape into an exciting world of danger and triumph. We read it rather in order to follow with meticulous interest and constant self-identification the hero's success in building up, step by step, out of whatever materials came to hand, a physical and moral replica of the world he had left behind him.

(Ross, 1985, p. 7)

New Lanark, the place Owen was later to make internationally famous, became, in a sense, his ‘island’, much like Crusoe's. There, like his hero, he used what came to hand, both in the physical environment and in an apparently less than efficient labour force. Nor, given Robert's first-hand experience of shopkeeping, were Crusoe's financial and commercial dealings likely to have gone unnoted. Accounts of exploration, like those of Captain Cook, would also prove attractive, but whether or not the actual ideas of the Enlightenment, which underpinned such works, had any impact on his thinking at that age is impossible to determine.

We might just note in passing that Owen, who learned to play the clarinet, enjoyed music and dancing. Both ultimately featured strongly in his social and educational thinking and were given a prominent place in the curriculum at New Lanark and later Owenite communities in Britain and the United States.

4.2 Apprenticeship in retailing c.1782–c.1789

Owen's apprenticeship coincided roughly with the initial development of New Lanark. Leaving home when he was ten or eleven years old, by his late teens he had already gained extensive experience in textile retailing. He started work at Stamford apprenticed to James McGuffog, a successful draper. McGuffog, a canny Scot, dealt in fine garments for well-to-do customers, to whom Owen no doubt learned to defer, and possibly also to emulate them when he was older. After completing his apprenticeship Owen moved to London where, thanks to McGuffog's recommendation, he was taken on as an assistant with Flint and Palmer, haberdashers, a large establishment, more like a department store. The clientele, because of their lower class, bought at cut prices for cash only. This was an altogether different environment from the gentility of Stamford and gave Owen experience of working in a large business with a rapid turnover. His next move in 1788 took him to Manchester, where he joined Sattersfield & Co., a firm of silk merchants and drapers catering to the middle class of the rapidly expanding town.

4.3 Business and enlightenment: Manchester 1789–99

Manchester's dynamic business environment, particularly that of the new cotton industry, presented many opportunities for enterprise, even to those with modest capital. By 1790 Owen had joined John Jones, probably another Welshman, making spinning machinery. The next logical move was into cotton spinning itself, and very quickly Owen had established a reputation as a manufacturer of fine yarn, selling as far afield as London and Scotland. When in 1792 one of the town's leading merchant capitalists, Peter Drinkwater (whose career replicated that of Dale), was looking for a new manager for his Bank Top Mill, Owen applied for and got the job. Others in the trade were incredulous when they heard that someone of the age of 21 had been appointed and at the huge salary of £300 per annum, comparable to a middle-class income (Owen, 1971, p. 29).

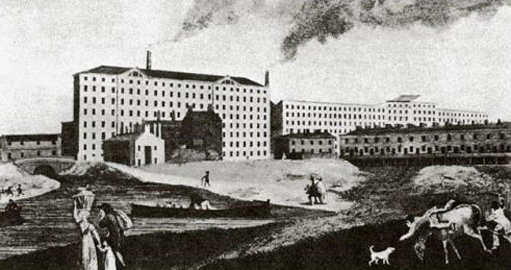

He may have joined the mercantile elite but Owen had enormous responsibilities: he was taken aback when he saw 500 workers, men, women and children, and all the new machines in Drinkwater's large modern factory. Not only was it one of the first to be driven by steam-power using a Boulton & Watt engine, but also its overall design had taken account of the latest thinking on fire-proofing, ventilation, light and hygiene (see Figure 4). While Drinkwater was no supporter of political reform he evidently took a paternal interest in the health and morals of his workforce, and this outlook must have influenced Owen, who had to implement his employer's orders. Owen was also to oversee Drinkwater's other mill, a water-powered factory housing Arkwright-type machinery at Northwich in Cheshire. He proved highly successful as a production and personnel manager, with a reputation for efficiency and innovation.

Owen's career in Manchester was further enhanced in 1795 when he left Drinkwater and joined the much larger Chorlton Twist Company. This had several other influential Manchester and London partners, substantial capital and potentially wide connections in the trade.

Exercise 4

Review the account of Owen's career to date. What skills could he highlight on his CV by 1795?

Discussion

In boyhood he accumulated a good all-round knowledge of the textile retail trade, some basic business skills and, perhaps most important, the necessary social skills to deal with people from a wide range of backgrounds. He subsequently proved highly entrepreneurial in his business dealings, embracing new technology and opportunities first in machine building and then in cotton spinning, in which he excelled. He gained considerable experience in personnel management and industrial relations in a factory environment. He progressed rapidly and although only in his mid-twenties was a partner in one of the leading spinning companies.

4.4 Manchester Literary & Philosophical Society and Board of Health

In the meantime Owen joined the town's social and intellectual elite, which like its politics was largely dominated by Dissenters. They were prominent in the Manchester Literary & Philosophical Society which Owen joined in 1793. There he associated with some significant reformers, heard papers on a wide range of intellectual, industrial and social topics, and himself presented papers dealing with such issues, including one on education.

The society was founded in 1781, the co-founders being Thomas Percival, Thomas Barnes and Thomas Henry. These and other leading members, such as John Ferriar, president when Owen joined, and John Dalton, a chemist and physicist, were in their different ways true sons of the Enlightenment. Percival (1740–1804), a physician and reformer, studied medicine at Edinburgh, associating with Scottish Enlightenment figures like David Hume and William Robertson, later completing his studies at Leiden, the Dutch university famed for its medical teaching. Interested in social conditions and public health, he probably first met Owen when inspecting new sanitary arrangements in Drinkwater's factory. Barnes (1747–1810), a distinguished scholar and Unitarian minister at Manchester's Cross Street Chapel, which Owen evidently attended, was also an educational reformer. Henry (1734–1816), an apothecary and chemist, helped pioneer the teaching of science and medicine in Manchester. Although Dalton (1766–1844) achieved greater fame, Ferriar (1761–1815) was the most interesting of the leading figures in the society. A physician at the infirmary, he was also interested in public health and factory conditions. His Medical Histories and Reflections (1792–8) clearly linked the spread of disease to social conditions. He was interested in literature and philosophy too, publishing in 1798 a study of the novelist Laurence Sterne (whom Owen had evidently read as a youth). If Owen was to learn more about social reform he could hardly have chosen better company.

The society covered a wide range of subjects: literary, philosophical, scientific, medical and humanitarian. It also took a great interest in the town's staple industry. Indeed, the first paper Owen heard was on ‘The nature and culture of Persian cotton’, to which he responded at Percival's prompting. Soon after joining in November 1793 he was precocious enough to turn the knowledge he possessed of the town's main industry to good account, reading a paper entitled ‘Remarks on the improvement of the cotton trade’. This went well, generating some interesting discussion; Percival was encouraging, and complimented him on his paper.

Owen delivered a second paper on ‘The utility of learning’ a month after the first. The title of the third, given in March 1795, was ‘Thoughts on the connection between universal happiness and practical mechanics’, the fourth, read in January 1796, being ‘On the origin of opinions, with a view to the improvement of social virtues’. These contributions all had some relevance to his subsequent philosophy and social psychology, especially his emphasis on the influence of environment in shaping character. Unfortunately none of his papers was printed and this may indicate that they were little more than commonplace. However, it seems highly likely that Owen carried some of the more important ideas he was then contemplating into his later work (Donnachie, 2000, pp. 61–2).

He may well have been influenced by other lectures and discussions on public health and on the growing problem of the poor, especially in an urban-industrial context. On 13 December 1793 he heard a paper by James Percival, Dr Percival's son, on ‘A philosophic enquiry into the nature and causes of contagion’, while on 19 April 1794 Samuel Bardsley, another physician, who later gave evidence in support of Robert Peel the Elder's factory bill (which became the Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802, the first to promote better conditions for children employed in factories), spoke on ‘Party prejudice, moral and political’. On 1 April 1796 Bardsley addressed himself to ‘Cursory observations, moral and political, on the state of the poor and lower classes in society’, a subject of great concern to the authorities and one underpinning much of Owen's later views on society.

The reforming instincts of these individuals, including Owen, found expression in another important organisation, the Board of Health, established in 1796. Because of its interests in factory conditions, and in child labour in particular, its influence ranged far beyond Manchester. Anticipating the campaign that ultimately led to Peel's bill, it gathered evidence from masters about the treatment and condition of apprentices in their mills. The Board solicited information on prevailing conditions from far and wide, Dale being one who responded in detail to its questionnaire. It is an interesting speculation that Owen might have learned for the first time about the regime at New Lanark when he scrutinised Dale's replies to questions about the treatment of his apprentices. Moreover, Owen perhaps already knew about the large Scottish mills, including Dale's. He could have read about them in the early volumes of Sir John Sinclair's Statistical Account of Scotland (1791–9), a major text of the Scottish Enlightenment, possessed by libraries like that of the Manchester society.

Exercise 5

Can you suggest what impact on Owen's intellectual development and ideas his participation in the Manchester Literary & Philosophical Society and the Board of Health might have had?

Discussion

First, he had the opportunity to extend his education through discussion, debate, reading Enlightenment thinkers and associating with other members. Second, his involvement helped formulate his own ideas about education and its role in society. Third, he gained an awareness of wider social issues, such as health and welfare, in and beyond the workplace.

Owen's activities on behalf of the Chorlton Twist Company involved travelling to see customers in Scotland, and it was during one of his visits to Glasgow, probably in 1797 or 1798, that he met Dale and inspected New Lanark for the first time. He was evidently impressed and given his knowledge of the industry could see that with better management it might prove highly profitable. He says that he also recognised its potential as a test-bed for his social ideas, but this may have been hindsight after the event (Owen, 1971, p. 46).

On subsequent visits he not only met Caroline, Dale's eldest daughter, but discovered that her father was anxious to dispose of some of his assets, including New Lanark. By 1799 Owen had negotiated the sale of the mills to his company on highly favourable terms, installed himself as managing partner, and married Caroline into the bargain. Although previously successful and financially secure Owen, as effective business heir and adviser to the now ailing Dale, was likely to rise still further and prosper greatly. As in Manchester Owen joined the Glasgow elite, identifying himself with social reform and associating with Scottish Enlightenment figures in the university and intellectual society of the city.

4.5 Owen at New Lanark 1800–c.1812

At New Lanark Owen quickly initiated changes, some of which he describes in the Second Essay. As in Manchester he placed much emphasis on environmental improvements such as street cleansing, better domestic hygiene, sanitation and water supply. Those designed to enhance efficiency and productivity included new rules and regulations about factory discipline and in 1803–4 installing new machinery. By 1806, and partly on the grounds of cost, he was abandoning the system of pauper apprentices (who had to be housed, clothed and fed) and instead switching to employing families with large numbers of children. At the same time he was also reviewing the merits of hiring children under the age of ten and enhancing the community's social and educational provision. The expense of the higher wages paid to older children and the cost of what they saw as unnecessary welfare caused several of the Manchester partners to withdraw. The partnership was reconstructed in 1810 and allowed Owen to proceed, perhaps more cautiously, with further innovations, possibly starting the buildings which were ultimately to serve as the ‘New Institution’ and school.

It may have been the expense involved, coupled with Owen's growing public profile, that caused the second group of partners to press for his dismissal as manager in 1812. Owen, as a major shareholder and the only one with the necessary expertise to run the enterprise, was in a strong position. But he also realised that to make further improvements he needed partners sympathetic to reform and had to publicise his ideas more widely. So, in moves designed to promote his own views about how New Lanark should be run, he initiated a propaganda exercise with the mills and community as its focus.

4.6 New Lanark and the Falls of Clyde

Let us take a moment to consider another aspect of New Lanark that was potentially of great importance to any propaganda campaign built around it. Big factories employing large numbers of youngsters were still unusual and so objects of curiosity. But New Lanark was unique given its proximity to the Falls of Clyde, the most spectacular waterfalls in Britain. By our period, the falls (see Figure 5) were celebrated in the works of leading artists and engravers (including Turner – see Plate 1, linked below), and set as they were in the romantic scenery then becoming fashionable were already a major tourist attraction visited by hundreds each year. As the roads were improved, more visitors came, often from Edinburgh or Glasgow, but also persons on tours from England or abroad, stopping off en route from the Lakes to the Trossachs or other more accessible parts of the southern Highlands. Literary visitors included William and Dorothy Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Robert Southey and many others, who visited both the falls and the village in the course of Scottish tours. The publicity value for the marketing of New Lanark was clearly considerable, as Owen must have realised, and he was to generate an upturn in visitor numbers from hundreds to thousands following the publication of A New View of Society.

Click to open Plate 1, J.M.W. Turner, The Falls of Clyde, c.1844–6, oil on canvas, 89 × 119.5 cm, Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight.

5 The background to the essays

5.1 The essays in context

Owen's public career effectively began in 1812, when he started to promote his ideas about popular education. He may have been thinking about this for some time. In 1810 he had evidently contacted Lord Liverpool (1770–1828), recently home secretary and by then secretary for war, about a proposed ‘Bill for the Formation of Character among the Poor and Working Classes’, aimed at establishing a national system of education. This object was a logical extension of Owen's experience among the workers at New Lanark, aligned to the possibilities of mass education under the monitorial system, which figures prominently in A New View of Society. Liverpool, understandably, was more concerned with defeating Napoleon than with popular education, and nothing came of the proposal. Owen may have been disappointed, concluding that his thoughts needed further clarification if they were to get anywhere in Parliament. But even in its wording the proposal provided the idea central to the essays on the formation of character (Donnachie, 2000, p. 115).

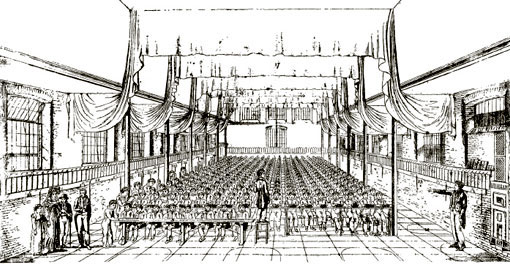

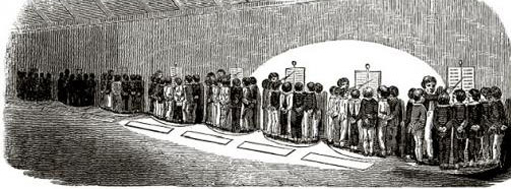

Another important development was Owen's involvement with Lancaster, whom he invited to visit Scotland in 1812. Lancaster had developed a method of schooling for working-class children based around rote learning and a system of badges and rewards (possibly the model for Owen's ‘silent monitor’, discussed in Section 6.4, used in the mills at New Lanark). By applying this system large numbers of pupils could be instructed simultaneously, with minimal expense on textbooks, something publishers must have regarded with alarm (see Figures 6a and 6b). Owen, flanked by professors from the university (Enlightenment Scotland having no fewer than four such seats of learning, compared with England's two) and by churchmen, chaired a dinner in Glasgow at which Lancaster explained his system, introducing one of his assistants to help demonstrate its key features. Owen's reply to Lancaster again emphasised the importance of working-class education as a means of social control and improved efficiency.

Owen's A Statement Regarding the New Lanark Establishment, published in 1812, was an important prelude to A New View of Society (see Figure 7). Partly a business prospectus and partly a summary of what he visualised for social provision at New Lanark, it describes his early management of the community. It also articulates his aspirations for the future and gives some indication of the way his thoughts were developing, many of which fed through to the essays. The extract in Exercise 6, below, will give you a flavour of what Owen was advocating for the community at this stage.

Exercise 6

Read the following extract from Owen's Statement. What, briefly, are his main proposals? What do they suggest about his proposals for social development and plans for communities?

It may be necessary to explain more particularly what I mean by those plans which I had in progress, for the further improvement of the community, and ultimate profit to the concern.

They were intended to increase the population, diminish its expense, add to its domestic comforts, and greatly improve its character. Towards effecting these purposes, a building has been erected, which may be termed the ‘New Institution’, situated in the centre of the establishment, with an enclosed area before it.

The objects intended to be accomplished by which are, first, To obtain for the children, from the age of two to five, a playground, in which they may be easily superintended, and their young minds properly directed, while the time of the parents will be much more usefully occupied, both for themselves and the establishment. This part of the plan arose from observing, that the tempers of children among the lower orders are generally spoiled, and vicious habits strongly formed, previous to the time when they are usually sent to school; and, to create the characters desired, these must be prevented, or as much as possible counteracted.

Secondly, To procure a large store-cellar, which was much wanted, and, by this arrangement, has been placed in the most advantageous situation for both the works and village; and it will be found to be of much use to the establishment.

Thirdly, A kitchen upon a large scale, in which food may be prepared of a better quality, and at a much lower rate, than individual families can now obtain it.

Fourthly, An eating room immediately adjoining the kitchen, one hundred and ten feet by forty within, in which those to whom it may be convenient may take all their regular meals.

Fifthly, The eating room, by an immediate removal of the tables to the ceiling, will afford space in which the younger part of the adults of the establishment may dance three nights in a week during winter, one hour each night; and which, under proper regulations, is expected to contribute essentially to their health.

Sixthly, Another room, the whole length of the building, being 140 feet long, 40 wide, and 20 high, which is to be the general education-room and church for the village, and those who attend the works.

Seventhly, This room was intended to be arranged, not only in the most convenient manner for the several branches of useful education enumerated, but also to serve for a lecture-room and church. The lectures were to be given in winter three nights in the week, alternately with dancing, and to be familiar discourses to instruct the population in their domestic economy, particularly in the methods they should adopt in training up their children, and forming their habits from their earliest infancy, in which, at present, they are deplorably ignorant.

And lastly, The plan also included the improvement of the road from the works and village to the old town of Lanark, which is now almost impassable for young children in winter, and in such a state as to prevent in a great measure the population of the latter from being available for the manufacturing purposes of the former, and from deriving any benefit from its institutions, which are calculated to educate the whole of the children in the neighbourhood, as well as the works are to give them employment afterwards.

Beneficial as these arrangements, connecting with the New Institution, must be to the individuals employed at the works, they will be at least equally advantageous, in a pecuniary view, to the proprietors of the establishment; for the whole expense of these combined operations will not exceed six thousand pounds, three thousand of which have been already expended; and, so far as my former experience enables me to judge of the consequences to arise from them, they cannot save less to the establishment than as many thousand pounds per annum, but probably much more.

(Owen, 1973, pp. 10–16)

Discussion

Owen says he wants to increase the population, reduce expense, enhance domestic arrangements and improve character. This will be done by developing the facilities of the ‘New Institution’, building a village store, establishing communal cooking and dining facilities, providing a dance hall, school and lecture rooms (doubling as a church), and improving communications with the neighbourhood. On a point of information, quite fascinating really, the ‘immediate removal of the tables to the ceiling’ was to be accomplished by means of hoists. This method of saving space was actually used elsewhere and it can be observed in the schoolroom scene (see Plate 2, linked below) where the ‘visual aids’ have been lifted off the floor.

Click to open Plate 2, G. Hunt, Dancing Class, The Institute, New Lanark, c.1820, coloured engraving, New Lanark Conservation Trust.

These proposals suggest that as early as 1812 Owen was already thinking in terms of social improvement driven by education and training. The communal arrangements for the supply of provisions and for cooking, dining and leisure activities are extremely interesting and might well have had wider application. There is also a hint of this in the penultimate paragraph, where Owen suggests these benefits will, in any case, be extended to the wider community beyond the confines of New Lanark.

We have no idea how many copies of the Statement he circulated, apart from those that ended up in the hands of potential partners. Possibly the work found its way into political circles, where anyone reading it would have been impressed by the idea that New Lanark under Owen's management

might be a model and example to the manufacturing community, which without some essential change in the formation of their characters, threatened, and now still more threatens, to revolutionise and ruin the empire.

(Owen, 1973, p. 4)

The idea that the character of the labouring class could be suitably moulded by these modest proposals, including whatever educational provision was required to make it more efficient (and thereby boost profits), was likely to have had considerable appeal in the increasingly volatile atmosphere of the time. As we have seen, political Radicalism in all its various forms was an anathema to the government, and the Luddites represented a direct physical threat to mill masters – or, worse, perhaps to the government itself. Riot and disorder threatened everywhere, but had not apparently reached the gates of New Lanark, another strong selling point. Equipped with copies of his statement Owen set out for London, hoping to put together a new partnership and secure control of the mills.

5.2 Owen in London 1812–14

Owen's visits to London, where he worked on the essays, coincided with the vital closing years of the Napoleonic Wars. He arrived in the metropolis to find it seething with news of momentous events on the Continent, especially Wellington's victories in the Peninsula and Napoleon's retreat from Moscow, of the course of the war in the United States, and, closer to home, of a series of political crises made more acute by the growing unrest in the country. While the international situation remained perilous and world events were to exercise a growing influence on Owen's later life, it was the prevailing politics and the personalities with whom he now associated which affected his reception.

As well as corresponding with ministers, Owen's activities in Manchester and Glasgow, and his successful management of New Lanark, meant that his ideas about social reform had almost certainly reached the government of Lord Liverpool. Liverpool by then headed a Tory administration, appointed by the Prince Regent following the assassination of the previous prime minister, Spencer Perceval, in May 1812. Liverpool, who had been present at the fall of the Bastille, was no great enthusiast for parliamentary reform. The essentially reactionary regime that prevailed during the first eight years of his government was to be counterbalanced by Liverpool's pragmatic approach to politics and the economy. Although the landed class still dominated Parliament, commercial and manufacturing interests were becoming increasingly important as industrialisation gained momentum.

Apart from Liverpool, Owen knew other members of the government, notably Viscount Sidmouth (1757–1844), the home secretary; Nicholas Vansittart (1766–1851), chancellor of the exchequer; and Robert Stewart, later Viscount Castlereagh (1769–1822), foreign secretary. Sidmouth, previously prime minister 1801–4, was charged with maintaining public order. Although much of the legislation under which he operated had been in place since the 1790s, he himself became identified with implementing further repressive measures. These included censorship of the press and pamphleteering, laws against meetings and demonstrations, and ultimately a raft of repressive legislation known as the ‘Six Acts’. This legislation, designed, among other objects, to prevent assembly that might lead to riot, was passed in 1819 following Peterloo (a Radical demonstration at St Peter's Field, Manchester, brutally attacked by militia after the Riot Act had been read), the bloodiest popular disturbance of the Regency. Vansittart was concerned about the economic impact of the war, increasing unemployment and the costs of the poor. Like Sidmouth, he was prepared to give tacit support to Owen's ideas. Owen came to know Castlereagh during his propaganda campaigns and was possibly assisted by him when he presented memorials on social reform to delegates at the Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle (Aachen) in 1818.

After the publication of the essays and his later plan for communities, many other prominent figures in politics, the churches and reforming circles were also willing to give Owen's views a hearing, though whether or not this was a commitment to action seemed to be one of the questions Owen consistently refused to address.

5.3 Further enlightened influences: Godwin, Place and Mill

What transpired during the first of many visits to London helps to explain the background to Owen's writing of the essays and shows how he set the concept of character formation into a larger frame, drawing extensively on the ideas and help of others. Ostensibly seeking new partners, he naturally sought out those likely to be sympathetic and rich enough to invest in New Lanark when it came on the market. Quite whom he contacted initially we do not know, but Lancaster and his rich Quaker supporters were prominent. At a dinner given for him in January 1813 by Daniel Stuart, a newspaper proprietor, Owen met William Godwin, the famous social philosopher and author of An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, which had been published in 1793. Godwin's work was a skilful summary of ideas generated during the Enlightenment and argued for a new social order stressing justice, freedom and equality for the individual. Education, private and public, figured prominently in Godwin's thinking, as did character formation and happiness. As Owen worked on the Second, Third and Fourth Essays, he was frequently at Godwin's house for breakfast, tea or dinner. Between January and May Owen met Godwin at least twice a week. Godwin later recorded that on one occasion he converted Owen from ‘self-love’ to ‘benevolence’, although the next time they met Owen claimed that he had been too hasty in altering his opinion. However, Owen's attempt to derive benevolence from a desire for happiness was not very different from Godwin's. Of course this does not prove that Owen's work owed much to Godwin's, but it probably exercised a great deal of influence, especially when allied to the ideas Owen himself had gleaned from his reading, through his association with enlightened thinkers in Manchester, Glasgow and Edinburgh, and from discussions with visiting reformers at New Lanark.

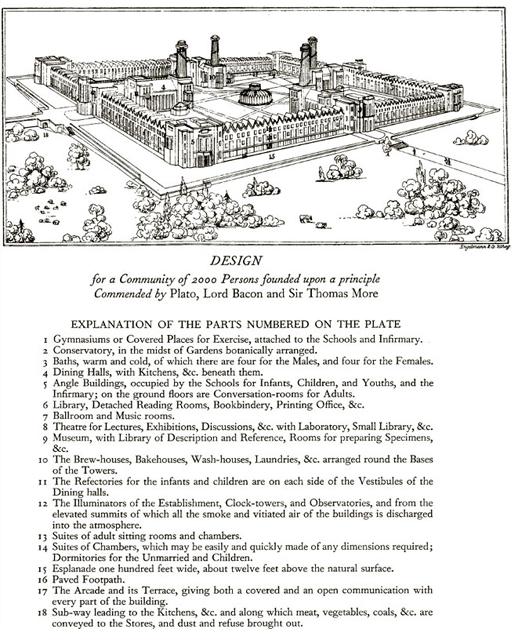

Owen was to list Godwin among his main literary companions, and some of the early socialist writers described the philosopher as his master. He certainly never acknowledged a direct debt to Political Justice, perhaps because he never properly read it. Yet many of the fundamental ideas and sometimes the actual phrasing of Owen's works resemble the doctrines of Political Justice. Like Godwin, Owen constructed his theory of progress on the Enlightenment premises that characters are formed by their circumstances, that vice is ignorance and that truth will ultimately prevail over error. Both individuals equated happiness with knowledge and spoke in the language of utility (meaning the capacity to satisfy human wants). Other features in common were the moral regeneration of humankind and the importance of economic reform in advance of political reform. They argued that the best way of eradicating the evils that beset society at the time was not the system of punishments and rewards advocated by the philosopher and reformer Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832), Owen's future partner, but by rational education and universal enlightenment. Both condemned political agitation, but favoured instead a voluntary redistribution of wealth, which Owen later hoped would be achieved through cooperation. Their ultimate social ideal was that of a decentralised society of small self-governing communities of the kind that Owen was to propose in his village scheme (Marshall, 1984, pp. 310–11). Since Godwin had fallen out of fashion Owen could be seen as his replacement for the new century (Locke, 1980, p. 262).

Moreover, Godwin introduced Owen to Francis Place (1751–1854), one of the most influential of the philosophic Radicals. Owen, Place recalled, was ‘a man of kind manners and good intentions, of an imperturbable temper, and an enthusiastic desire to promote the happiness of mankind’. ‘A few interviews made us friends’, said Place, ‘and he told me he possessed the means, and was resolved to produce a great change in the manners and habits of the whole of the people, from the exalted to the most depressed’. (Owen often spoke about ‘possessing the means’ or ‘holding a secret’, possibly allusions to birth control.) He also told Place that most of the existing institutions prejudiced welfare and happiness, but that his proposals were so simple and so obviously beneficial that any thinking person could understand them. Owen evidently presented Place with a manuscript, asking if he would read and correct it for him, but whether this consisted of the first two essays or all four is unclear. Friendship apart, Place was incredulous that Owen believed he was the first to observe that ‘man was a creature of circumstances’ and that ‘on this supposed discovery he founded his system’ (quoted in Donnachie, 2000, p. 116).

Place was another early advocate of birth control, which he linked to the ideas of the demographer and economist the Reverend Thomas Malthus (1763–1834). Malthus's pessimistic predictions of over-population (also noted in Owen's essays) helped fuel the debate about the future of the Poor Law. This traditional system of parish relief, Malthus thought, misguidedly increased the misery of the poor by providing doles which encouraged procreation, larger families, and hence still more pressure on food and subsistence goods that were already in short supply. Malthus's economic thinking may also have had some impact on Owen. Unlike the followers of the economist David Ricardo (1772–1823), Malthus saw agriculture as intrinsically more productive than manufactures, and Owen's later community plan placed great emphasis on intensive farming as a means of self-sufficiency.

Among other intellectuals with whom Owen associated during 1813–14 was James Mill (1773–1836), economist, philosopher and close associate of Owen's prospective partner, Bentham. Although Owen never acknowledged the fact, it was probably Place and Mill who edited A New View of Society and gave the essays the clarity that is missing from some of his later works. Even his supporters thought much of his writing was very woolly. Place was greatly offended not only by the second comprehensive edition of the essays, published in 1816, which contained material he had earlier read and rejected, but also by Owen's apparent arrogance in the face of reasoned criticism. Moreover, as far as Place was concerned, practical politics were clearly not Owen's strong point. Owen steered well clear of suggesting, far less articulating, any agenda for political as opposed to social reform. Perhaps he did not want to prejudice his immediate plans, realising that the authorities were unlikely to look with much favour on anything that remotely whiffed of Radicalism. Pragmatism, as in his financial and business affairs, was the watchword.

6 The essays

6.1 Overview

Having looked at the contexts and background, let us turn now to the essays themselves. I have used the edition of 1837, which was based on the second edition of the complete work, dating from 1816. However, it is worth noting that Owen made revisions and additions to subsequent English, French and American versions, so the reader will come across occasional references and allusions to developments which are out of context with the period when the essays were first written. I shall draw to your attention any that affect your reading of the shortened version of the essays. I also want to convey directly the flavour of the whole work, which has been edited to this end by Alison Hiley.

6.2 The dedications

Let us start with the dedications, which are both intriguing and of considerable interest.

Exercise 7

Read Owen's dedications heading each essay. To whom are the essays dedicated and can you suggest why?

Click document below to open the First Essay

Robert Owen, A New View of Society

Click document below to open the Second Essay

Robert Owen, A New View of Society

Click document below to open the Third Essay

Robert Owen, A New View of Society

Click document below to open the Fourth Essay

Robert Owen, A New View of Society

Discussion

The essays are dedicated in turn to William Wilberforce, the British public, the ‘Superintendents of Manufactories’ and the Prince Regent. Obviously Owen's appeals were directed at reformers like Wilberforce, the public generally, mill owners or other employers like himself who might be persuaded to support his principles, and lastly not just the prime minister or other senior figures in the government but the constitutional head of state, the Prince Regent himself. Owen may well have cited the last with a view to royal patronage (which he subsequently enjoyed for a time).

Exercise 8

Does anything strike you as strange about dedicating the essays to both William Wilberforce and the Prince Regent?

Discussion

Wilberforce was a well-known supporter of reform, while the Prince Regent might be regarded as conservative, if not reactionary in his views, certainly about political (if not social) reform.

Wilberforce, the Evangelical Christian MP, was reckoned to be one of the greatest humanitarians of his generation, a reputation by that time well established through his leading role in the anti-slavery movement. His reforming instincts extended to a whole range of other issues, including the condition of the poor and of factory workers, especially children. So Owen's appeal to him is interesting and highly relevant. It suggests a close association between them even at this early date, especially if Wilberforce had given permission for the dedication (but we don't know positively, since so little of Owen's correspondence before 1820 survives).

Note: For more information on Wilberforce, see OpenLearn course A207_9.

As far as that to the Prince Regent goes, this is another intriguing dedication and quite a cachet if it had been obtained with official permission, possibly via Sidmouth or even Liverpool himself. George, having previously consorted with the Whig opposition, but now retaining a Tory administration, could hardly be described as a reformer. However, two of his brothers, the Dukes of Sussex and Kent, both identified themselves with social reform, supporting some of Owen's ideas for easing distress and poverty and Owenite organisations promoting these objects.

We might just note that when the essays were assembled for publication as a book in 1816, Owen dropped Wilberforce from the dedication. Had he complained, perhaps, because he did not want to be associated with the anti-religious views that appeared in the essays and that Owen was beginning to voice on public platforms? On the other hand, perhaps Owen felt uncomfortable with the thought that his fortune and those of his partners at New Lanark had been built, even indirectly, on slavery. The Prince Regent, prior to ascending the throne in 1820, headed the dedication in subsequent editions.

6.3 First Essay

The earliest essay, written under the nom de plume of ‘one of His Majesty's Justices of the Peace for the County of Lanark’ (if intended to provide Owen with anonymity this was a thin disguise, given the content) and entitled ‘On the Formation of Character’, is prefixed by the famous precept, central to the ‘New View’, that:

Any general character, from the best to the worst, from the most ignorant to the most enlightened, may be given to any community, even to the world at large, by the application of proper means; which means are to a great extent at the command and under the control of those who have influence in the affairs of men.

A variant of this central theme stresses the individual rather than the community or society at large by emphasising, as Owen does in the Third Essay, that ‘the character of man is formed FOR – not BY himself’. We might also note that despite the apparent gender bias here and in the essays themselves, in the context of his time Owen was no male chauvinist; indeed, he held radical views on gender relationships, marriage, birth control and divorce (mostly kept to himself, but to which he would sometimes allude publicly). We can take it that by ‘men’ he was inclusive of women, and point out that at the same time he attached great importance to women's role as homemakers and educators and to equality generally. Indeed, equality (including uniformity of dress) was to become one of the foundations of later Owenite communities.

Exercise 9

Now read the extracts from the First Essay, linked below, and in doing so consider the following questions:

What are Owen's views about the social structure and class divisions? And what, in his opinion, characterises the main social classes?

Which Enlightenment ideal does he refer to at this juncture and how is it to be achieved?

Are there examples of good practice which Owen says might be followed? Do they seem appropriate comparisons with New Lanark?

Click document below to open the First Essay

Discussion

In his analysis of the social order Owen identifies the poor and working classes as his major category, at over 15 million, or ‘nearly three-fourths’ of the total population (he refers to the latest census of 1811, which recorded 18 million persons in Britain and Ireland; in fact a group of more than 15 million would have represented over 80 per cent of the total). He reckons that the great majority have character defects due to lack of ‘proper guidance or direction’ (p. 108). The worst are the poor and uneducated, who are effectively trained to form a criminal class, while the rest of the population are educated to a system of society with the wrong values – as evidenced, for example, by the vicious punishment of criminals raised in the system.

The Enlightenment notion to which Owen refers is social progress through the use of reason. His aims are improved ‘character formation’ and the happiness of individuals and of society at large through rational education.

Owen identifies several interesting examples of how his ideas could be applied, including through the educational innovations of Bell and Lancaster and, at the community level, his own experiments at New Lanark. He alludes to other establishments on the Continent which have been visited by British reformers, in Bavaria (which as a Napoleonic satellite-kingdom could have been regarded, albeit briefly, as a model of enlightened rule) and the Netherlands. The last had always been a country where the underprivileged had been treated sympathetically. During the Batavian Republic (1795–1806), when French revolutionary ideas prevailed, the poor were described as ‘children of the state’ – surely a liberal view even in a modern democracy. Note, however, that the ‘Pauper Colonies’ to which Owen refers were not established until later (see Figure 8).

While the examples Owen cites here are interesting instances of how the poor could be employed, these are not really appropriate comparisons. New Lanark was a large capitalist enterprise in a rapidly developing industry, whereas the European examples were essentially agricultural or urban workhouses. This might have raised problems for public perceptions of any future Owenite community scheme.

We might just note that among the many visual aids Owen produced to accompany his lectures were nine cubes based on a table in Patrick Colquhoun's Treatise on the Population, Wealth, Power and Resources of the British Empire (1814), eight representing volumetrically eight classes of society, while the ninth represented the total population. The largest of the eight was almost four inches square, while that representing royalty, the lords and bishops was just a quarter of an inch square. The royal dukes who were patrons of Owen's plan were apparently fascinated by the cubes, which, should this have been necessary, vividly demonstrated their position in society relative to the working and pauper classes.

The closing section of the essay is certainly a powerful critique of the prevailing distress and the condition of the poor and a vindication of the strategies Owen is proposing for improvement.

Exercise 10

Take a moment now to reflect on what Owen is trying to say in his First Essay and how Enlightenment ideas underpin it, summarising your thoughts in a few sentences.

Click document below to open the First Essay

Discussion

To summarise the First Essay, Owen believes that environmental planning and education hold the key to the formation of character. So suitably moulded characters can produce a pacific and harmonious working class. The social problems created by industrialisation and the oppressive working conditions and long hours in factories ought to be addressed by the authorities, otherwise ‘general disorder must ensue’ (p.108). ‘Happiness’, however, can even be equated with ‘pecuniary profits’, as Owen himself would presently demonstrate (pp.112–13). Much of this argument derived from the Enlightenment ideals of reason dispelling darkness from the human mind, the reasoned conditioning of people, and happiness generated by rational means.

Little of this, as Place observed, was really new. The influences of environment on individuals and society came from Rousseau and other thinkers of the Enlightenment era, whose ideas Owen had probably first read in Manchester. According to Owen, the fundamental concept that character and environment are mutually related could readily be applied in an industrial context. There paternalistic methods might produce a humanitarian regime and generate greater productivity and profit, in which, theoretically, all could share. Unity and mutual cooperation, however, were concepts for the future. At this time too Owen's thoughts on education were probably still being formulated, but, expanding on his earlier statement of 1812, he duly acknowledges his debt to Lancaster and to Bell – who, as we have seen, pioneered the simultaneous instruction of large numbers of children. This was likely to appeal in the first instance to other educational reformers, including Owen's Quaker associates. They were involved with a body known as the British and Foreign School Society (established as the Royal Lancasterian Society in 1808) to promote non-denominational popular education, and were anxious to encourage the development of schools applying Lancaster's principles.

6.4 Second Essay

As a preliminary to the Second Essay, Owen says that he will enhance further his discussion of his underlying principles and then begin to explain to his readers how they can be applied in practice. Notice too the prologue for the Second Essay (p. 113) , quoting Vansittart's view that ‘if we cannot reconcile, all opinions, let us endeavour to unite all hearts’, a ringing phrase often quoted by Owen in later publications and widely adopted as one of the most popular Owenite homilies.

The Second Essay is important because in it Owen expands further on the defects of society as he sees them, especially as regards the neglect of education in the making of individuals and society at large, the perverse or negative attitudes to charity, and crime and punishment. The central concern, however, is to provide the reader with a detailed description of New Lanark as he found it and the reforms his management has introduced.

Exercise 11

Read over the Second Essay, linked below, and think about the following questions:

What is rational instruction designed to promote?

Why, in Owen's opinion, has the present system failed society?

What, according to Owen, promotes crime and how does he view the law and system of punishment?

Click document below to open the Second Essay

Discussion

Children the world over are creatures of their environment and their circumstances, and attitudes of parents and teachers will shape their characters. From infancy, they have no control over their education and the resulting characters with which they are endowed. Society needs to take responsibility for rational instruction which with ‘perseverance under judicious management’ (p. 114) will inculcate sound sentiments and manners in infancy and later life.

The system has failed partly due to the ignorance of previous generations (which Owen finds odd because the printing press has long provided the means of disseminating rational, enlightened ideas) and partly because existing moral and religious instruction cannot counteract such unfavourable circumstances.

Poverty explains high levels of crime (which, as we have seen, was a growing concern of the time). According to Owen, the poor are trapped in a spiral of crime, much of the legislation is punitive, and (in another remarkably modern critique) the law is administered by those who have no real understanding of the environment and circumstances in which crimes are committed. Judges could well be in the dock, says Owen, if they had been raised among the poor!

Much of Owen's critique of the law, to which he returned at public meetings in 1817, seems to come from Bentham. As you can see, Owen also urges us to visit London's gaols, where we shall find plenty more evidence of the adverse circumstances which have shaped the characters of the luckless prisoners incarcerated there (p. 116).

Now we come to Owen's account of New Lanark under his management, which is really the core of the Second Essay.

Exercise 12

Read Owen's description of New Lanark in its entirety, and as you do so think about the following questions:

What is Owen's aim in providing this account, and how do you think this affects his treatment?

What were the conditions Owen found on assuming management at New Lanark?

How did he set about improving matters, and what sorts of response did he meet from management, workers and villagers?

Discussion

This is an interesting question, as Owen must have realised that he had to provide evidence that his ideas, so far as he had been able to apply them up to that point, actually worked in practice. While his account can be taken at face value as an accurate picture of the works and community, I think it is highly likely that Owen deliberately downplayed his father-in-law's achievements and talked up his own.

A great deal could be said here about the conditions at New Lanark before Owen took over, and summarising it all is far from easy. First, Owen gives a history of the community, which pretty much replicates the brief account above, but places a great deal more emphasis on the negative aspects of the story. The workforce included the orphans and the families, apparently assembled at random, and all accommodated in a makeshift way either in parts of the factory or in the village built nearby. Because Dale had many other interests he seldom visited the works, management being entrusted to ‘servants with more or less power’ (p. 117).

In the next paragraph follows another famous passage which ultimately entered the annals of Owenism by stating that at New Lanark the ‘population lived in idleness, in poverty, in almost every kind of crime; consequently, in debt, out of health, and in misery’ (p. 117). To make matters worse there was also a strong sectarian influence, probably disputes between members of the Established Church of Scotland and Dissenting sects (Dale's included?), which had a highly negative effect on the community (this is Owen's earliest attack on religious sectarianism and an enlightened plea for toleration, as it happens).

Second, and more positively, Dale is praised for his benevolence in providing for the pauper apprentices accommodation, food, clothing, medical care and education. However, in Owen's opinion, many were too young to work in the mills for long hours, and the regime largely negated the good it might have done. Further, when the apprenticeships had been completed those who could not be kept on sometimes took to the streets in either Edinburgh or Glasgow (like other cities, these were notorious for criminality). If this is the best that can be done, says Owen, what must the worse be like by comparison?

At this point Owen, cloaked as the ‘stranger’ (p. 119), comes on the scene, deploying his Manchester experience to clean the place up. After appraising the situation he launches a major programme of reform in both the workplace and the community.

In the mills Owen introduced inspections to cut down petty pilfering (which was widespread in factories), and improved work practices and workflows, poor time-keeping and absenteeism. These improvements generated mixed responses. Some of the managers resented Owen's style (and were either side-stepped or dismissed). But Owen eventually convinced the workers of his good intentions through philanthropy. During a lay-off caused by the US embargo on trade with Britain he continued paying wages to his workers, a generous gesture by the standard of most mill owners.