Delacroix

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 19 April 2024, 9:21 PM

Delacroix

Introduction

In this course you will be introduced to a variety of Delacroix’s work and see how his paintings relate to the cultural transition from Enlightenment to Romanticism.

You will study Delacroix’s early career, his classical background, the development of Romantic ideas and their incorporation into his work. You will have the opportunity to study some of his most important paintings and compare them to works favouring a Neoclassical approach. You will also be able to see how his themes, subjects and style were influenced by Romantic ideas, the exotic and the Oriental. Through this you will develop an understanding of the classic-Romantic balance that how his work was influenced by cultural change of that period and to some extent contributed to the progression from Enlightenment to Romanticism.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of Level 2 study in Arts and Humanities.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

identify those aspects of Delacroix’s art that qualify it as ‘Romantic’

understand the interplay between classicism and Romanticism in Delacroix’s art

appreciate the nature of Delacroix’s fascination with the Oriental and the exotic even before he visited Morocco.

1 Overview

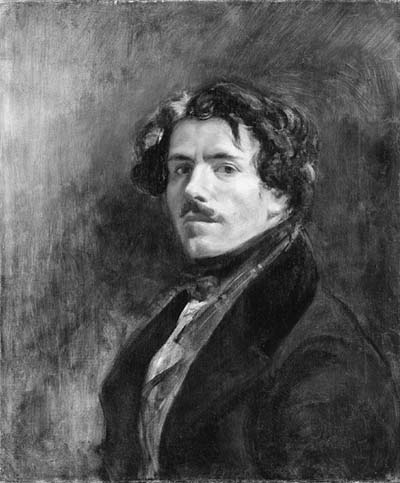

1.1 Delacroix’s background

Ferdinand-Victor-Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) was an artist raised amid the heroism and turmoil of Napoleon’s regime but whose artistic career began in earnest after Waterloo. His father (who died in 1805) held important administrative, ambassadorial and ministerial posts during both the Revolution and Napoleon’s rule. His brothers had fought for Napoleon, one being killed heroically in 1807 at the battle of Friedland, the other a general who was made a baron of the empire before being retired (as was the custom) on half-pay. As Delacroix’s mother had died in 1814, when he was still fairly young, he was left in the care of an older sister, who had little time to devote to him and struggled with the precarious financial position of the family. Delacroix’s own (artistic) glory was to come later and he is often described as part of the ‘generation of 1820’ (Spitzer, 2001, p.9). This generation, coming of age between 1814 and 1825, had witnessed the disappointed hopes of Napoleonic empire, and it has been suggested that this sense of loss helped to determine their Romantic mindset (see Brookner, 2000). Having seen the Old Regime swept away, they looked on as the monarchy was restored after Napoleon’s defeat. Those who had earlier supported the Revolution now tried their luck as royalists. Although he quickly gained a reputation as a rebellious Romantic, Delacroix was always ill at ease with this perception of him. Like many artists of the Romantic generation, he sought public recognition. As you will see, his career was to be a constant struggle to reconcile a radical aesthetic with the demands of public taste and longstanding, well-respected artistic traditions.

1.2 Ideas and influences

The Oriental and the exotic played a central role in this process of artistic negotiation and reconciliation. The Enlightenment’s preoccupation with ‘exotic’ lands as part of an indirect critique of western European societies increasingly competed with visions of the East as a site of fantasy, desire and sensuous pleasure. Like the Prince Regent’s Pavilion, Delacroix’s work also exemplified in many respects a specifically Romantic concern with the Oriental and exotic as a means of unleashing and expressing personal desire. His interest lay largely in Greece, Turkey and Morocco. In a typical switch from an enlightened to a Romantic perspective, the psychological and social ideas opened up by the Enlightenment’s consideration of such places gave way to the application of those ideas to a process of artistic self-exploration and self-expression. And yet, as we shall see, Delacroix was not always so clearly on the side of Romanticism. His 1832 journey to Morocco would be a crucial, transforming influence on his career.

First, it is necessary to establish how Delacroix developed his artistic thought, values and practice in the early part of his career in order to appreciate the full impact on his art of a concern with Oriental and exotic subjects. Our starting point will be the painting that caused the greatest furore of the artist’s career.

2 The Death of Sardanapalus

2.1 Inspiration for the Death of Sardanapalus

Plate 1 is a reproduction of Delacroix’s The Death of Sardanapalus, believed to have been completed sometime between November 1827 and January 1828.

Clickto see Plate 1: Eugène Delacroix,The Death of Sardanapalus

It draws on a legend, fabricated in the Persika by the Greek writer Ksetias (fourth century BCE), that had already featured in a play by Byron entitled Sardanapalus, published in 1821. It concerns an Assyrian ruler whose palace was threatened by his rebellious subjects. Sardanapalus, descendant of Semiramis, was the last king of Nineveh, a city roughly halfway between the Mediterranean and the Caspian Sea in present-day Iraq. According to the legend, he died in 876 BCE. In order to avoid the humiliation of defeat by his subjects (a theme that would have evoked, in Delacroix’s era, the revolutionary mob), he ordered himself, his palace and all his prized possessions (including his favourite concubine, Myrrha) to be burned and destroyed. In Delacroix’s version, unlike Byron’s, Sardanapalus meets his fate not just with Myrrha, but with an entire roomful of concubines and slaves. Delacroix probably drew on a number of sources in the visualisation of this incident. Apart from Byron, it’s thought that he was also influenced by the Greek historian Diodorus (first century CE), the Roman historian Quintus Curtius (also first century CE) and possibly an engraving of a pseudo-Etruscan relief of the incident (see Johnson, 1981, pp.117–18). It has also been suggested (see Lambertson, 2002) that the conception and iconography of Delacroix’s painting might have been inspired by similar work by Charles-Émile Champmartin, an artist with whom Delacroix was acquainted. Champmartin had visited the Near East and in 1828 completed a large-scale Oriental massacre scene, Massacre of the Janissaries: see Plate 2.

Click to see Plate 2: Charles-Émile Champmartin, Massacre of the Janissaries

However, the uncommissioned Sardanapalus was probably, above all, a product of Delacroix’s fancy. Archaeological accuracy was certainly not possible as Nineveh had not yet been excavated.

2.2 Sardanapalus – subject and composition

The following explanatory text was published in the booklet accompanying the paintings at the 1827–8 Salon, where Delacroix’s canvas was exhibited:

Death of Sardanapalus. The rebels besieged him in his palace … Lying on a superb bed, atop an immense pyre, Sardanapalus orders his eunuchs and palace officers to slit the throats of his women, his pages, and even his horses and favourite dogs; none of the objects that served his pleasure should survive him … Aisheh, a Bactrian woman, couldn’t bear that a slave should kill her and hung herself from the columns supporting the vault … Baleah, Sardanapalus’s cupbearer, finally set fire to the pyre and threw himself in.

(Quoted in Johnson, 1981, pp.114–15; trans. Walsh)

Aisheh is in the centre of the top of the painting; Baleah is in the centre of the painting’s right-hand edge, accompanied by a figure holding his hand to his head. He is signalling to Sardanapalus that, as the rebels have gained ground, the order to set fire to the palace has already been given. We can see flames in the background. Sardanapalus himself reclines on his bed, in the top left-hand corner, gazing in Baleah’s direction. The diagonal between him and Baleah divides the painting into two sections, each full of incident. To the right of the bed, as Aisheh hangs herself, a slave is preparing to kill a woman lower down. To the left of the bed, we see a woman carrying poison in a jewel-encrusted jug; other figures kill themselves, are convulsed by fear or lie dying. In the right foreground a nude woman is having her throat slit and in the bottom left-hand corner a black slave is killing a horse.

2.3 A passionate reaction

The painting provoked a furore because both its subject and the manner in which it was painted were felt to be excessive: this delirious orgy, playing on Byronic notions of fieriness and Faustian concoctions of creative and destructive energies, was not what critics and public had come to expect of grand history painting. Its massive size (just under four by five metres) magnified its effect. In fact, the painting had only narrowly been voted into the exhibition by the Salon jury. The following critique, by Étienne-Jean Delécluze, a former pupil of David, was typical:

M. Delacroix’s Sardanapalus found favour neither with the public nor with the artists. One tried in vain to get at the thoughts entertained by the painter in composing his work; the intelligence of the viewer could not penetrate the subject, the elements of which are isolated, where the eye cannot find its way within the confusion of lines and colours, where the first rules of art seem to have been deliberately violated. Sardanapalus is a mistake on the part of the painter.

(Quoted in Jobert, 1998, p.83)

Most assessments, like this one, slated the painting’s lack of compositional logic and its riot of colour. Delacroix was said to be ‘hotheaded’; his work had gone ‘beyond the bounds of independence and originality’; in the ‘delirium of his creation’ he had been carried ‘beyond all bounds’; ‘almost unanimously the spectators find it ridiculous’ (from reviews quoted in Jobert, 1998, pp.81–3). The Director of Fine Arts summoned Delacroix in order to tell him that if he wished to receive future government commissions (which were, in any case, relatively rare in restoration France) he would have to alter his style: the government refused to purchase the work. The painting remained unsold until 1846, when it was bought by a banker, John Wilson.

Let’s look now at the causes of the widespread antipathy to this painting, a ‘mistake’ that would motivate Delacroix, in the remainder of his career, to be better understood.

2.4 Controversial colour and composition – exercise

In order to understand the furore created by Sardanapalus it will be helpful to compare the work with others more acceptable to the domain of public art. With this in mind, you are asked here to work on two short exercises designed to explore the radical nature of Delacroix’s deathbed scene. In each case, you will be asked to compare images and extract their principal similarities and differences.

Exercise 1

Compare Delacroix’s Sardanapalus and David’s Andromache mourning Hector (Plates 1 and 3). Make brief comparisons between these paintings, focusing on the general organisation of the picture space; the position of the deathbeds and the use of linear perspective (the use of straight lines that appear to recede into the picture space and converge, thus suggesting depth or distance); and the implied position (if any) of the viewer.

Discussion

The space represented by David’s painting is intelligible, logical and ordered. There is a clear sense of linear perspective in the receding lines of the floor which lead the viewer’s eye into the scene and to an identifiable convergence point or viewer’s ‘eye level’ just above Andromache’s head. The elements of the painting relate clearly to one another in scale so that, for example, it is obvious that Andromache is closer to us than the body of Hector, which is, in turn, closer to us than the background colonnade. There is a clear recession into the depth or distance from the viewer, based on an imagined series of vertical planes or layers slicing through the picture space, rather like parallel vertical slots or dividers in an imaginary three-dimensional box. The deathbed is arranged horizontally along one of these planes so that it offers a dignified profile of the dead hero’s corpse. The two principal figures stand out clearly from a dark, neutral background and are arranged symmetrically so that the overall composition is balanced.

By contrast, Delacroix’s painting offers no clear recession into depth. There is no logical sense of scale or perspective. For example, the woman reclining behind the nude with arching back seems to be too close to her to appear so small. Sardanapalus’s head appears diminutive by comparison with those of the foreground figures. Figures and objects are tumbled together in a way that makes it difficult to say with any confidence which are supposed to be closer to the viewer than others. Look, for example, at the foreground figures, who seem to form a frieze – like a ‘cut-out’ imposed uneasily on the rest of the painting. And finally the floor, far from providing a clear path for the viewer’s eye to follow, seems to cave in at the foot of the painting so that it is difficult to imagine how, for example, the rearing horse has entered the scene at all. The deathbed itself is almost propelled, like a magic carpet, from the top left-hand corner, and slices diagonally through the scene without any clear relationship to the angle of the walls around it. There is no easily identifiable point from which to view this scene, which also appears to have been cropped in an unnatural way, as if the real clues to what is going on are out-of-frame. If anything we, as viewers, are suspended above the chasm apparently about to engulf Sardanapalus’s rich treasures. Faces are painted as if we see them all from the same height – there is no use of foreshortening – and yet we know this cannot possibly be so, as logic would dictate that we view some chins from below, some heads from above.

Click to see Plate 1: Eugène Delacroix,The Death of Sardanapalus

Click to see Plate 3: Jacques-Louis David Andromache mourning Hector

2.5 Neoclassical – the established style

All of the disorientating effects of Delacroix’s composition were noted by his contemporaries, whose mindset was very much attuned to more legible treatments of picture space. This was exemplified by David, whose approach to painting represents a particularly austere interpretation of the neoclassical style established in eighteenth-century French art. It contributed to the political aims of the Revolution and First Empire, was admired and emulated by many artists, and remained influential in the Academy and critical circles of Delacroix’s time. It was derived from a restrained, dignified branch of Renaissance classicism, drawing principally on Raphael and popularised in France through the example of artists such as the seventeenth-century master Nicolas Poussin (see Figure 1). Later eighteenth-century artists such as Jean-Baptiste Greuze (see Figure 2) adapted Poussin’s neoclassical deathbed formula (a frieze-like composition structured around straight, horizontal lines and uncluttered spaces), which also found dramatic expression in David’s Death of Socrates. Moreover, in 1827, the year in which Delacroix’s Sardanapalus was being completed, Ingres, by then a famous representative of Neoclassicism, exhibited his Apotheosis of Homer (Plate 4). Although he was perceived as departing radically from David’s approach, he had nevertheless studied under him and was identified as adhering in important ways to the master’s neoclassical example.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Click to see Plate 4: Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, The Apotheosis of Homer

In many neoclassical paintings there is a clear, logical, planimetric structure to the composition: that is, a series of implied horizontal and vertical planes (straight layers or ‘slices’ through the imagined three-dimensional space of the painting) along which the whole is structured, so that the composition remains taut, stable and balanced. This stability was often achieved partly through the use of the straight horizontal lines of classical architecture, which locked figures and objects into a geometric ‘grid’. Figures, derived from antique statuary, are idealised rather than realistic, and arranged hierarchically so that heroes and protagonists and the planes on which they are located are clearly dominant. Neoclassical compositions of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries express the traditional values of a classical style: simplicity, unity, order, idealism, balance, symmetry and a general respect for rules and reason. They also adhere to the traditional classical practice of studying antique statuary and the posed academic model as a basis for figure drawing: if ‘nature’ was to be ‘imitated’ this had to be in a highly selective, idealising and refining way. The neoclassical style developed and championed by David offers a particularly striking version of the classical characterised by a stark linearity: clearly delineated, outlined or contoured figures and objects, standing out from a neutral, non-distracting background, and often arranged horizontally so that they line up directly in front of the viewer.

The surface finish of a neoclassical painting is smooth, so that there is no distracting surface ‘dazzle’ or appeals to the senses of touch and sight that would detract from intellectual impact. Eloquent gesture, designed to assist narrative intelligibility, is also characteristic. In the years preceding the French Revolution, the Neoclassicism introduced by David, with its stripped bare, linear, austere style and republican overtones, had been controversial (see Plate 5, The Lictors returning to Brutus the Bodies of his Sons). David’s pupils – Girodet, Gérard, Guérin and Ingres – subsequently assisted their master in consolidating the status of Neoclassicism by adapting its potential to the requirements of the Napoleonic empire. Generally, this elevated style became accepted as appropriate to the morally and intellectually elevated history genre favoured by the Academy and required for grand, public display. It suited a broad cultural preference for the archetypal and the didactic. By the time Delacroix began his career as a painter, Neoclassicism had lost much of its Davidian radicalism and had become a style with which the Academy was both familiar and comfortable.

Click to see Plate 5: Jacques-Louis David, The Lictors returning to Brutus the Bodies of his Sons

2.6 An alternative deathbed tradition

Delacroix does not draw on this neoclassical tradition. He uses an alternative deathbed tradition, in which the bed is artificially raised and tilted towards the viewer to allow a fuller view of the dead or dying. See, for example, Ménageot’s Leonardo de Vinci, dying in the Arms of Francis the First (Figure 3) and Rembrandt’s etching of The Death of the Virgin (Figure 4). Delacroix tilts and raises his deathbed to an exceptional degree, however, so that death completely dominates the surrounding space. In art of an earlier period, this would probably have been attributed simply to a lack of technical competence; see, for instance, Figure 5, John Souch’s Sir Thomas Aston at the Deathbed of his Wife. Delacroix did in fact secure the services of a specialist in perspective to map out the lines of the architecture in the painting: he admitted to difficulties with the rules of perspective. Given the contemporary dominance of the neoclassical aesthetic, however, it is likely that the issues driving his approach went beyond matters of competence. In his painting the conventional, neoclassical horizontal format is subverted by the strong sense of diagonal movement. This subversion of compositional order is reminiscent of Goya’s St Francis Borja attending a Dying Impenitent (Figure 6), in which the corpse, surrounded by blood and demons, appears to slide diagonally from a horizontal bed towards a dark foreground chasm, thus disrupting the underlying geometric framework. Delacroix had been introduced to Goya’s work through his acquaintance in Paris with the Guillemardet family, whose father had served as ambassador in Spain. Earlier than most of his contemporaries, Delacroix became familiar with engravings of Goya’s works, including the Caprichos. It is unlikely that he knew the St Francis Borja, which had been a specific commission for Valencia Cathedral. It is highly probable, however, that Goya’s work and style influenced Delacroix’s works of the 1820s. Like Goya, Delacroix presents death in a way that challenges the static compositions of Neoclassicism.

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

2.7 Interpreting the classical form

The female nudes in The Death of Sardanapalus are of the curvaceous, fleshy, wild-haired type favoured by Rubens, slightly streamlined for a contemporary audience. We can see in the work the influence of Rubens’s Landing of Maria de’ Medici at Marseilles (1621–5) (Plate 6). The standing nude in the foreground of Delacroix’s painting was painted from life, but was influenced by a nereid (sea-nymph) in Rubens’s Landing as well as by one of the nudes in his Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus (Plate 7). The shoulder and upper arm of the man stabbing Delacroix’s nude were possibly influenced by the Triton (sea-god) in the left foreground of the Landing. These fleshy women are of a very different kind from the sleek, elongated nudes of Ingres (see his Grande Odalisque, Plate 8). The neoclassical was both linear and idealist in its approach. Ingres’s nudes are not only clearly contoured, but also the result of a Platonic conception of beauty which operated via a careful selection of elements from nature and the elimination of defects. It was not until the 1830s, however, that critics and commentators confronted the stylistic gulf that separated Delacroix from Ingres (see Carrington Shelton, 2000, p.728).

Click to see Plate 6: Peter Paul Rubens, The Landing of Marie de’ Medici at Marseilles, 3 November 1600

Click to see Plate 7: Peter Paul Rubens, The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus

Click to see Plate 8: Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, La Grande Odalisque

Rubens represents a very different interpretation of ‘the classical’ from that favoured by the neoclassicists. His history paintings often use the luminous diagonals (shafts of light falling diagonally across the canvas), turbulent movement, luscious colour and sparkling objects that exerted such a profound influence on Delacroix, as on many other Romantic artists. It is interesting to speculate on the reasons for Delacroix’s preferences. They were probably, in part, temperamental: following the example of Rubens would have allowed him to work in a more painterly manner, with freer brushstrokes and with less fear of the laws of geometry and of the precision of a clear contour that had been so important in the works of Poussin and other sources for Neoclassicism. Also, in this case the style suits the subject: what better way to represent a collapsing regime than by means of a compositional technique that encapsulates collapse? The ‘orgy’ of colour is also appropriate to the subject, but was equally controversial.

2.8 Colour and light – exercise

Exercise 2

Compare the effects of colour and light in Sardanapalus with those in David’s Andromache mourning Hector (Plate 3). What similarities and differences can you see? (You may find it helpful to look also at Plates 9–12, preparatory works for Delacroix’s painting.)

Click to see Plate 3: Jacques-Louis David Andromache mourning Hector

Discussion

Both paintings contain highly coloured areas, but these are more dominant in Delacroix’s work than in David’s. The boy in David’s painting wears a bright red cloak, but this is a relatively modest colour note in a generally moderately coloured work. In Delacroix’s painting there are darker, more restrained areas – for example, in the top right-hand corner – but (and this is a lot easier to see in the original) much of the canvas is dominated by red and gold so that the general effect is opulent. David’s quieter colour harmonies do not distract from the linear and intellectual appeal of the image. Delacroix uses colour in a more assertive way, not only to unify his painting but also to create an overall sensuousness.

In David’s painting the grieving Andromache is very dramatically highlighted by a spotlight effect, which helps to focus our attention. In Sardanapalus several figures are highlighted so that there is no obvious focal point. These patches of light, like many of the figures in the painting, which result from individual studies (see Plates 9–12), remain distinct and separate from one another. (This is incidentally a departure from the traditional academic process of using broad areas of light and shadow to unify a painting and direct the viewer’s eye towards a primary figure.) In David’s canvas Andromache provides a centre of emotional and visual interest, but the bright light falling on her unites with and flows into the gentler light illuminating Hector. In Delacroix’s painting it is areas of colour, rather than the suggestion of light falling on objects, that glue together the various areas of the composition.

Click to see Plate 9: Eugène Delacroix, sketch for The Death of Sardanapalus

Click to see Plate 10: Eugène Delacroix, sketch of a female nude

Click to see Plate 11: Eugène Delacroix's sketch for The Death of Sardanapalus,

2.9 Painterly techniques

A sensuous use of colour subverted the neoclassical aesthetic, in which moral and intellectual messages – or, at the very least, a concept of ‘noble form’ – were intended to dominate. In the case of Delacroix, this attention to the effects of colour is heightened by a concern with the textural qualities of paint. In order to produce a matt but bright surface, he applied thin layers of oil glaze to an initial lay-in of distemper (see ten-Doesschate Chu, 2001, p.102). It is thought that he was aiming to produce an effect similar to that of pastels and watercolours – many of his preliminary studies for the painting are in pastels. Indeed, Delacroix learned from various other artists. For example, he established a firm friendship with Richard Parkes Bonington, the English watercolourist. He later recalled how he and Bonington had met in around 1816, when Bonington was working on studies in the gallery of the Louvre. The two artists met again when Delacroix visited England in 1825 and later shared a studio in Paris. Delacroix admired and tried to emulate the lightness of touch and sparkle of Bonington’s technique (see Plate 13)

Click to see Plate 13: Richard Parkes Bonington, Rouen from the Quays

Whereas neoclassical work aimed to preserve a smoothed-down paint surface produced by the use of delicate, fine brushstrokes, Delacroix applied to the finished canvas of Sardanapalus a technique called flossing. Possibly borrowed from Constable, whose Haywain Delacroix had seen in the Salon of 1824, this process involves the application of short delicate strokes of colour on top of the ‘finished’ paint surface and enhances the impression of sparkling light. This clearly demonstrates Delacroix’s adventurous approach to technique. He also borrowed from Constable, in this and earlier works, the method of applying thin colour cross-hatchings to distemper in order to achieve his shadows. Traditionally, shadows had been painted as thin, dark glazes, with no colour interest at all: they had had a muddy, dirty effect, as the local (actual) colour of an object had been mixed with black. Constable and Delacroix revolutionised the painting of shadow by representing it as composed of strands of colour. This was a far cry from conventional academic chiaroscuro. Chiaroscuro is the use of light and shade to model form (that is, to suggest the three-dimensional presence of objects and figures) or to create tonal effects, from the subtle to the dramatic.

2.10 Colour versus line

Rubens versus Poussin, colour versus line – these were the polarities around which much debate in France had been structured since the late seventeenth century, when the Royal Academy of Painting had been founded. The defence of line or contour had been linked with idealisation and the idea of absolute, perfect beauty derived from drawing skills based on observation of antique statuary. Colour had been associated with the emotive and the sensual and given less status: it satisfied the eye rather than the mind. This polarity was, of course, artificial. Most artists were concerned with both colour and line. It was therefore often a matter of perceived priorities. An article in the review L’Artiste of 1832 anticipated the Delacroix-Ingres polarity that would become well established from 1834 onwards:

It’s the battle between antique and modern genius. M. Ingres belongs in many respects to the heroic age of the Greeks; he is perhaps more of a sculptor than a painter; he occupies himself exclusively with line and form, purposefully neglecting animation and colour … M. Delacroix, in contrast, wilfully sacrifices the rigours of drawing to the demands of the drama he depicts; his manner, less chaste and reserved, more ardent and animated, emphasizes the brilliance of colour over the purity of line.

(Quoted in Carrington Shelton, 2000, pp.731–2)

2.11 Birth of the ‘Romantic’

The ‘ardent and animated’ aspects of Delacroix’s work made commentators describe his large canvases of the 1820s as ‘Romantic’. By the end of the decade, he was regarded by many younger artists as the leader of a new, modern school of painting that in a spirit of revolutionary fervour had thrown off the shackles of a worn-out classicism. And yet, when a stranger who had seen Sardanapalusreferred to Delacroix as the ‘Victor Hugo of painting’, the artist responded, ‘You are mistaken, Sir, I am a pure classicist’ (quoted in Wilson-Smith, 1992, p.78). To put this in context: the 1827 Preface to Cromwell by the writer and critic Victor Hugo, an acknowledged leader of the Romantics, is a manifesto accompanying a drama he had written. It is a call to arms to fellow Romantics to cast aside the old ways and embrace a Romantic credo. The main thrust of the Preface is blatantly anti-classical: Hugo demands that writers should no longer work under the tyranny of classical rules or genres. Arguing that there must be a new spirit of liberty in art, he declares, ‘There are no rules; there are no models! Or rather there are no rules except the general rules of nature’ (Hugo, 1949, p.41). While he acknowledges that writers must proceed in a way compatible with their chosen subject, Hugo also denounces the servile imitation of any source. Delacroix was determined, in spite of all the criticism, to hold on to a good opinion of his controversial painting, but resented the suggested identification with this cutting-edge coterie. In the following section we’ll look at some of the reasons behind this crisis of artistic identity. In the meantime, the main point to take away from this section is that Delacroix’s painting of Sardanapalus was felt to be too extreme in its departure from the compositional and colour effects of neoclassical art.

3 Delacroix – classic or Romantic?

3.1 A classical education

This section maps out some of the aspects of Delacroix’s early career that help to explain his approach in Sardanapalus.

Delacroix consistently asserted his allegiance to classicism, in the broadest sense of an interest in the history and culture of ancient Greece and Rome. It had played a significant part in his early education. As a boy he attended the Lycée Impérial in Paris, which was known, before and after the empire period, as the Collège Louis-le-Grand. There he was schooled in the classics, philosophy, history and literature, studying Latin and Greek authors, as well as French seventeenth-century classic literary works such as those of Racine and Corneille. From 1815 he studied in the studio of the neoclassicist Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, where he was immersed in subjects from antiquity (see Plate 14, Guérin’s The Return of Marcus Sextus). Like his contemporaries, Delacroix regarded classicism as a matter not only of subject matter and content (the inclusion in a painting of sections of ancient Roman architecture, antique drapes and costumes, historical and mythological tales from antiquity) but also, as we have seen, of style. In Guérin’s studio Delacroix learned the rudiments of a neoclassical style of painting. Guérin eventually became the director of the French Academy (of painting) in Rome, an appointment that demonstrated his approval by the establishment. From 1816 to 1822 Delacroix also attended classes at the École des Beaux-Arts, where he received further instruction in an academic, classical style of painting, making studies from plaster casts of antique sculpture. And throughout his life Delacroix visited and copied paintings in the Louvre by artists such as Rubens, Raphael, Correggio, Titian, Veronese and Rembrandt. These were all masters from whom student painters were expected to learn, even though they did not represent a cohesive classical tradition.

Click to see Plate 14: Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, The Return of Marcus Sextus

3.2 The influence of Géricault and Gros

It was at the École des Beaux-Arts that Delacroix met Théodore Géricault, whose Romantic canvases, such as The Raft of the Medusa (Plate 15), made an impact on him. Delacroix posed as one of the foreground figures in this work, which was somewhat controversial due to its heroic and realistic treatment of a contemporary news story of French naval troops and settlers, shipwrecked on their way to Senegal and signalling to another vessel for help. The painting’s departure from grand, literary and classical themes was regarded as a disturbing challenge to tradition, given its adoption of the scale and importance of history painting. The graphic, realistic portrayal of human suffering was an implicit challenge to classical idealisation. In order to draw the bodies of the figures, the artist had made studies from actual corpses and severed limbs. Nevertheless, Géricault’s essential inspiration remained the academic, classical nude (he had seen and admired work by Michelangelo). What he achieved was a radical reworking of classical norms. He massed together writhing figures into a composition, marked by dramatic diagonal lines, that threatens to topple the ‘stable’ classical pyramidal figure groups it contains (one surmounted by a signalling figure, the other by a mast). The final result, a muscular and energetic reinterpretation of a classical style, provided an example that was to be well taken by Delacroix.

Click to see Plate 15: Théodore Géricault, The Raft of the Medusa

Géricault’s challenge to prevailing notions of the ‘classical’ or ‘classic’ was among many that influenced the early career of Delacroix. During the Napoleonic empire, Antoine-Jean Gros introduced a more flamboyant, colourist style that, in its treatment of scale and pictorial space, departed from neoclassical norms. Gros was later to regret what he saw as some of the misdirected energy of his youth, but Delacroix greatly admired him. He was able to view Gros’s large Napoleonic canvases after the older artist had praised a painting discussed in more detail below, Delacroix’s 1822 Salon entry, The Barque of Dante (Plate 16):

I idolized Gros’s talent, which still is for me at the time of this writing [that is, at the end of Delacroix’s life], and after everything that I have seen, one of the most remarkable in the history of painting. Pure chance led me to meeting Gros, who, learning that I was the painter of the picture in question, complimented me with such unbelievable warmth that for the rest of my life I have been immune to all flattery. He ended by telling me, after bringing out all its merits, that it was a polished Rubens. For him, who adored Rubens and who had been brought up in the severe school of David, it was the highest of praise. He asked me if he could do anything for me. I asked him forthwith to let me see his famous paintings of the Empire, which at that time were in the obscurity of his workshop, since they could not be openly exhibited because of the times [restoration France] and because of their subjects. He left me there for four hours, alone or with him, in the middle of his sketches, his preliminary works.

(Quoted in Jobert, 1998, pp.68–9)

Click to see Plate 16: Eugène Delacroix, The Barque of Dante

3.3 A Baroque influence

Another influence on Delacroix, as we have seen, was Rubens, who represented a particular strain of classicism often referred to as Baroque. This term was first applied to painting by nineteenth-century art historians. It carries overtones of the capricious and the florid, and is used of a style of painting dating roughly from the late Renaissance to the end of the seventeenth century. Rubens had studied and copied ancient Roman statues, friezes and tombs. He made drawings that are as austere in their linear classicism as those of any artist, and he painted the religious and mythological subjects expected of classical art. However, he moved on to paint figures that are more fleshy and realistic than statuesque, and came to prefer dramatic to static compositions. Here is one recent attempt, by newspaper critic Brian Sewell, to sum up the Baroque style. Sewell responds impatiently to what he perceives to be inadequate definitions:

Baroque composition is, in essence, a construction based on logic and perspective, but so swept away by serpentine lines and dramatic diagonals (and so co-ordinated by them), so daring in strenuous movements towards and away from the spectator that the frame and picture plane seem scarcely able to contain them; in extreme Baroque pictures elements swirl and flow as though subject to some cosmic force, contrasts of light and shadow are employed to add both drama and realism, and every constituent is seen to be a support for the core subject, no matter how remote from it.

(Sewell, 2001)

This Baroque energy is evident in Rubens, but it also features, less explicitly, in the work of artists not normally characterised as Baroque. For example, in the Bacchanalian revels painted by Nicolas Poussin in A Bacchanalian Revel before a Term (a ‘term’ in this context is a bust placed on a tapered pillar) and in his Rape of the Sabines (see Plates 17 and 18), diagonal movement, drama and vivid colour are imposed on more conventional classical settings in order to produce an effect very different from that of his Testament of Eudamidas (see Figure 1).

Click to see Figure 1: Nicolas Poussin, The Testament of Eudamidas

Click to see Plate 17: Nicolas Poussin, A Bacchanalian Revel before a Term

Click to see Plate 18: Nicolas Poussin, The Rape of the Sabines

Some of Poussin’s clients required this colourist, dramatic style: his ‘pure’ classicism was susceptible to Baroque adaptation, although you may have noticed the clearly controlled linearity that remains in his Bacchanalian Revel. In these works by Poussin, the movement and the colour are controlled with a balanced and harmonious composition.

3.4 Neoclassical and the Baroque – a delicate balance

As, from the seventeenth century onwards, French aesthetic preferences polarised around Poussin and Rubens (perceived champions, respectively, of line and colour), the argument was largely one of degree: the proportion of swirling movement and colour to balance, order, contour and harmony. The late nineteenth-century philosopher Nietzsche characterised Greek tragedy, and indeed all art, as a tension between the Dionysiac (Bacchanalian forces of whirling revelry, after Dionysus, the Greek god of wine) and the Apolline (the forces of poetic harmony, order and reason, after Apollo, the Greek god of beauty, civilisation and the arts). This tension is evident in Delacroix’s painting, as the Apolline neoclassical comes under attack from the Romantic Dionysiac: the lack of obvious focal point or compositional unity seems to drive his work even beyond the Baroque. For many contemporaries, Sardanapalus had got the balance wrong, and much of the remainder of Delacroix’s career aimed to address this. He did not, however, follow the neoclassicists Gérard, Guérin and Ingres. While aiming for more ordered compositions, he continued to see Michelangelo and Rubens as the sources of a classicism more muscular, dynamic and vital than that championed by the Academy and David’s followers. He sought a more expressive classicism, better adapted to the prevailing culture of the Romantic:

Delacroix’s pictorial practice was shaped by conflict. Aiming at both simplicity of effect and a richness of colour and texture, striving for the calm of Veronese and the turbulence of Rubens, Delacroix was forever torn between his classic sense of order and his innate Romantic impulse. To resolve that conflict was the driving force of his art.

(ten-Doesschate Chu, 2001, p.107)

Click to see Plate 6: Peter Paul Rubens, The Landing of Marie de’ Medici at Marseilles, 3 November 1600

3.5 The Barque of Dante – innovation within tradition

The urge to depart from tradition, without abandoning classicism, is apparent in Delacroix’s earliest Salon exhibits. Displayed there in 1822, some years before the Sardanapalus, The Barque of Dante (see Plate 16) depicts an episode from the Inferno, a poem written by the medieval Italian poet Dante. The poet imagines being rowed, in the company of the Roman poet Virgil, across the lake surrounding the infernal city of Dis, which is in flames in the background. Sinners are clinging to and trying to climb into the boat. The work, not commissioned and on a subject of Delacroix’s own choice, was bought by the government for its museum of modern art, the Musée du Luxembourg. Although it does not conform to the practices of Neoclassicism, its use of tonal effects and nudes is very similar to that of Michelangelo, an alternative classical source. It lies recognisably within the tradition of grand history painting, and the composition (with symmetrical, central figures surrounded by a balanced arrangement of other figures) is classical. As we saw earlier, Gros regarded it as a ‘polished Rubens’. Its use of colour is novel but fairly restrained. There is a mass of grey enlivened by skilfully placed patches of green, red and blue. Influenced by Rubens’s Landing of Maria de’ Medici at Marseilles (Plate 6), the droplets of water on the nudes’ bodies show all the colours of the spectrum. (The work was retouched in 1859, however, so we must take care in our assumptions about what was in the ‘original’.) Rubens had certainly established a tradition of dramatic seascapes (see Plate 19, The Miracle of St Walburga). Charles Delécluze found Delacroix’s painting as a whole a ‘real mess’ (quoted in Jobert, 1998, p.69), but admired the drawing and colour of the main figures. In a review of the 1822 Salon, however, Adolphe Thiers saw the work as evidence of Delacroix’s genius: ‘I find this power wild, ardent but natural, which effortlessly yields to its own force … I do not think I am wrong: M. Delacroix has the gift of genius’ (quoted in Jobert, 1998, p.69). With his first Salon, Delacroix thus gained a reputation as an innovator who worked within, rather than overthrowing, tradition. The choice of subject was novel for a history painter and showed a departure from the usual repertoire of topics from classical antiquity and national history.

Click to see Plate 19: Nicolas Poussin Peter Paul Rubens, The Miracle of St Walburga

3.6 Massacres of Chios – challenging the establishment

If the Barque had marked Delacroix out as an innovator, his next important Salon exhibit, Massacres of Chios (1824) (see Plate 20), was much bolder in its challenge to the establishment. The painting is a fictionalised account of the aftermath of the Turks’ massacre of 20,000 Greeks on the island of Chios, which occurred in 1822 during the Greek Wars of Independence. The massacre was a reprisal for Turkish losses caused by a Greek uprising against Turkish occupation. Again the painting was not commissioned and depicts a subject of Delacroix’s own choosing. It was exhibited at the 1824 Salon, where it won a medal. Although the painting does not conform to the neoclassical norm, there are aspects of its composition which are classical. The figures, for example, are grouped into triangles or pyramids, and there is an overall sense of balance – disrupted slightly on the right-hand side by the Turk rearing up on his horse, literally dominating the Greek victims. Unconventionally, however, in place of the centralised hero or object of interest of a classical composition, there is a gaping hole that allows a view on to distant hills. This lack of a hero, of a visual centre and of a unity of interest (the figures seem singularly uninterested in one another) subverted the normal conventions of history painting. Many critics found the subject too ugly, the figures too cold, passive and defeated, and the technique too rough, disjointed and jarring.

Click to see Plate 20: Eugène Delacroix, Massacres of Chios

For one critic loyal to the Davidian school, Pierre-Athanase Chauvin, this was all too much. He regarded Delacroix’s work as the ultimate Romantic insult to classical beauty:

It is not to arrest the development of our young artists that I am so quick to indicate the steps by which a distinguished painter, the teacher of their teachers [David], led the historical genre to the apogee of its glory; it is rather to establish a necessary point of comparison, which ought to humiliate no one; it is, in short, to avoid the words ‘classic’ and ‘romantic’, or, if you will, to explain them clearly and precisely. The classic is drawn from la belle nature it touches us, it moves us, it satisfies heart and mind together. The more one studies, the more one discovers its beauties; one leaves it with regret, and returns to it with pleasure. The romantic, on the contrary, has something forced, unnatural, which at first glance shocks the eye and upon examination repels it. The artist, in delirium, uselessly combines atrocious scenes, sheds blood, tears out innards, paints despair and agony. Uselessly again, he obtains partial effects in the midst of a thousand extravagances, and makes people who know nothing about it shout, ‘Miracle!’ Posterity will never accept such works, and contemporaries of good faith will grow weary of them; they are weary already. Conclusion: I call Leonidas [a painting by David] … classic, and the Massacres of Chios romantic.

(Quoted in Jobert, 1998, pp.75–6)

3.7 Massacres of Chios – a critical stir

Chauvin viewed both Delacroix’s subject and his technique as barbaric: the painting dealt with no eternal truths and delivered no inspiring lesson. Other complaints were voiced about the rough brushwork that called attention to itself in such a non-academic manner. The ‘cadaverous tint’ of the bodies also drew criticism. Gros, whose own compositional experiments had inspired Delacroix, allegedly called the picture the ‘massacre of painting’ (quoted in Johnson, 1981, p.87), while Stendhal, aware of the influence of Gros and (probably) disappointed by the lack of overt heroism in the work, said the ‘massacre’ was more like a ‘plague’ (quoted in Wright, 2001, p.32) – in Delacroix’s painting, the red-rimmed eyes of the old woman are derived from Gros’s Bonaparte Visiting the Plague-Stricken of Jaffa (see Plate 21). However, the use of colour in Delacroix’s work is again adventurous and reflects the influence of Rubens. There are coloured shadows (for example in the shadow cast by the old woman’s wide sleeve) and a striking balancing of complementary reds and greens, blues and yellows. This use of complementaries to generate colour interest and contrast was taken to new lengths by Delacroix. The general colour key of the landscape, however, is light and fresh, influenced by Constable and Bonington. Before the Salon opened, and having just seen some paintings by Constable destined for the same exhibition, Delacroix retouched his painting using fine brushstrokes, additional glazes, highlights and varnish to make the surface sparkle. Some commentators found the colours too bright and clashing. Although certain artists, such as Gérard and Girodet, did admire the painting, it created the kind of furore that was by now associated by conservative critics with attention-seeking Romantics. The choice of a contemporary, topical subject raised similar suspicions: in the academic classical tradition, subjects were usually drawn from a literary, mythological or historical past that could be viewed from a safe distance. The fact, however, that the government awarded Delacroix a medal and subsequently bought the painting shows that it was capable of occasional liberal and innovative insight. The picture had caused a stir and the artist was seen as a rising star, irrespective of the carping criticism he attracted. Government medals provided a means of acknowledging, rather than approving, an artist’s achievement.

Click to see Plate 21: Gros’s Bonaparte Visiting the Plague-Stricken of Jaffa

3.8 Transcending the Romantic-classic divide

Much of the ground for the reception of Sardanapalus had now been prepared. The classic-Romantic divide, with David’s followers on one side and Gros and Géricault on the other, was already well established by the time Delacroix produced his painting of mass suicide. Contemporary viewers would have detected Romantic allegiances in, for example, the horse and black slave, probably influenced by Gros. And yet Delacroix never came to terms with the perception of himself as the enemy of classicism. It bothered him that he should be regarded as someone out of control, swept along by the energies and eddies of an uncontrollable genius. He was stung by reactions to what he perceived as a generally successful work:

I am sick of this whole Salon. They’ll end by making me believe that I’ve had a real fiasco. And yet I’m not entirely convinced. Some say it’s a total failure, that The Death of Sardanapalus means the death of the Romantics, since that’s what they call us; others bluntly declare that I’m inganno [in error], but that they’d rather be wrong with me than be right like a thousand others who have good sense on their side, if you like, but who deserve damnation in the name of the soul and of the imagination. My own opinion is that they’re all idiots, that this picture has both qualities and faults, and that if there are some things in it that I could wish better done, there are plenty of others that I hold myself fortunate to have done and that they might well wish to have equalled … It’s all quite pitiful and would not deserve a moment’s attention except in so far as it directly jeopardizes my wholly material interests, in other words, cash.

(Letter to Charles Soulier, Paris, 11 March 1828, in Stewart, 1971, pp.145–6)

This final remark by Delacroix was prompted, perhaps, by the fact that he saw the state as the only realistic purchaser of a painting of this grandeur. Indeed, this was the situation faced by most history painters of the day working outside the remit of Church or private commissions. The artist’s journal shows him to be a shrewd book-keeper, market researcher and businessman. Far from considering himself the witless victim of artistic delirium, Delacroix was, by the mid-1820s, an accomplished socialite – a regular attender at Parisian salons, acquiring expertise in the kind of self-publicity that would flourish later in his career. He assumed the role and appearance of an English dandy, undemonstrative and impassive (see Figure 7). Furthermore, his method of producing paintings was painstaking and founded on fine judgement: he usually made preparatory sketches, both compositional and of individual figures, based on the observation of models. In other words, his work does include a measure of the refined study of nature, control and intelligence expected of the classical artist. We can see from this how each art form develops its own way of allocating labels to styles. Delacroix greatly admired Mozart’s music, preferring it to Beethoven’s, whose ‘wild originality’ was legendary. Beethoven’s music was, he felt, ‘obscure and … lacking in unity’ – the reason being that Beethoven ‘turns his back on eternal principles: Mozart never’ (quoted in Vaughan, 1978, p.246). The eternal and the unifying: these were the hallmarks of classical order and composition. While Delacroix did admire, in the work of musicians, artists and writers such as Beethoven, Rubens and Shakespeare, qualities of sketchiness and the unfinished, he nevertheless felt that the consummate, classical art of Racine and Mozart represented a form of eternal beauty (Hannoosh, 1995, pp.71–4).

3.9 Delacroix’s early career – exercise

Exercise 3

In order to sum up your work on this section, jot down some notes on how Delacroix's early career might be seen as moving away from a respect for the classical tradition and for the reason and order demanded of classical composition.

Discussion

Delacroix’s early education and training were dominated by the classical tradition. When he began to exhibit works at the Salon, he retained some aspects of classical composition (order, symmetry, the use of academic nudes). However, he worked within a tradition of Baroque classicism, which made him stand out from the neoclassicists of his age, and as the Baroque aspects of his work intensified, he became vulnerable to the charge of abandoning what was seen as a correct or pure form of the classical for Romanticism.

Clearly, there came a point at which Baroque classicism redefined itself, in the eyes of contemporaries, as Romanticism. This was because, as a style, it became associated with a host of ideas about artistic creativity and about the role of art in the broader culture. Like Goethe’s Faust, Delacroix’s painting seems to transcend the classic-Romantic divide. In the next section we shall look at the reasons why Delacroix’s contemporaries placed him in the Romantic camp.

4 The Romantic artist and the creative process

4.1 The Romantic aesthetic

In a journal entry of October 1822 Delacroix expressed the view that artists, unlike writers, don’t have to say everything explicitly:

The writer says nearly everything to be understood. In painting a mysterious bond is established between the souls of the sitters [The French alternative is personnages (see Joubin, 1996, p.29), which might alternatively be rendered as ‘figures’.] and those of the spectator. He sees the faces, external nature; but he thinks inwardly the true thought that is common to all people, to which some give body in writing, yet altering its fragile essence. Thus grosser spirits are more moved by writers than by musicians and painters.

(Pach, 1938, p.41)

This notion of the artist mediating between the souls of his models and those of his spectators lay at the heart of the Romantic aesthetic. Also central to Romanticism was the idea that the artist dealt essentially with the inexplicit, with the suggested rather than with the clearly expressed. To the Romantics, sculpture was inferior to painting because of its material status: solid and three-dimensional, it was too close to real life and too explicit in its mode of representing our experience of the world. Music, on the other hand, enjoyed a special status since it excelled in inexplicit evocation. For the same reason, the sketch, as a means of artistic expression, came to enjoy a higher status: it was even less specific than a finished painting in its powers of evocation and in its ability to generate meaning. For Delacroix and the Romantics, this lack of specificity facilitated a deeper, primal process of communication. To his contemporaries, therefore, well acquainted with such views, the sketchiness or (apparently) rough brushwork of Delacroix’s works signified a Romantic mindset. Both Turner and Constable used the sweeping brushstroke innovatively in the context of the dominant aesthetic of the classical picturesque and how this technique was seen as a means of gaining access to the artist's individual identity. Romantic artists such as Turner, Constable and Delacroix were, in this respect, exploring and engaging with a phenomenon that had been rationally identified and analysed, if not practised, by Enlightenment theorists.

4.2 Imagination and inspiration

Even William Gilpin, whose own artistic practice was so formula-bound, recognised the importance of leaving something to the imagination. In his Observations … on … the Mountains, and Lakes of Cumberland, and Westmoreland, he remarks:

We may be pleased with the description, and the picture: but the soul can feel neither, unless the force of our own imagination aid the poet’s, or the painter’s art; exalt the idea; and picture things unseen.

(Gilpin, 1973, vol.II, p.11)

Gilpin considered that sketches, unlike finished works, offer the imagination the opportunity to ‘create something more itself’ (1973, vol.II, p.16). Although he was suspicious of artists who let their imaginations roam too far from the ‘simple standard of nature, in it’s [sic] most beautiful forms’, he nevertheless glimpsed in passing the potential of a less constrained approach to creativity. Similarly, the Enlightenment art critic, Denis Diderot, had distinguished between clay models and finished sculptures, the former being much closer to the initial moment of feeling and inspiration:

The artist puts his fire into the clay, then when he goes at the stone boredom and indifference set in, the boredom and indifference adhere to the chisel and penetrate the marble, unless the sculptor is possessed of an inextinguishable zeal like that the old poet [Homer] attributed to his gods.

(Quoted in Goodman, 1995, p.170)

Once again, then, we see how the Romantics put into practice some of the possibilities perceived intellectually in the Enlightenment: the development from one to the other was an organic process. For instance, Delacroix’s The Murder of the Bishop of Liège (1829) (see Plate 22) depicts an episode from a novel by Sir Walter Scott, Quentin Durward (1823). It shows the Bishop of Liège about to have his throat cut by rebels in his château, which has recently been captured by William de la Marck, ‘the Boar of Ardennes’, who now stands in front of the bishop and gives the order for him to be murdered on the spot. The painting is more ‘finished’ than the sketch which preceded it (see Plate 23), yet some critics found that it retained too much of the looseness of a sketch in, for example, the faces of the foreground figures. Like Turner and Constable, Delacroix retains in his paintings something of the original ‘fire’ of the sketch.

Click to see Plate 22: Eugène Delacroix, The Murder of the Bishop of Liège

Click to see Plate 23: Eugène Delacroix, sketch for The Murder of the Bishop of Liège

4.3 Delacroix – sensitivity and suffering

Although in public Delacroix assumed the demeanour of the accomplished socialite (he dined regularly with Hugo, Alfred de Musset and other writers, and was friendly with Chopin and George Sand, among others), his letters and journal entries speak of a keen sensitivity that, he believed, infused his art and set him apart from ‘the common herd’:

As soon as a man is intelligent, his first duty is to be honest and strong. It is no use to try to forget, there is something virtuous in him that demands to be obeyed and satisfied. What do you think has been the life of men who have raised themselves above the common herd? Constant strife. Struggle against the idleness that is common to them and to the average man, when it is a question of writing, if he is a writer: because his genius clamors to be manifested; and it is not merely through some vain lust to be famed that he obeys it – it is through conscience. Let those who work lukewarmly be silent: what do they know of work dictated by inspiration? This fear, this dread of awakening the slumbering lion, whose roarings stir your very being. To sum up: be strong, simple, and true; there is your problem for all times, and it is always useful.

(Pach, 1938, p.94)

Delacroix was dedicated to hard work and the conquering of natural idleness. The extract above from his journal shows how a large part of that work involved an authentic expression of the ‘slumbering lion’ of inspiration. This involved suffering. The notion of the solitary, suffering artist was familiar to the Romantic côterie of Delacroix’s day. Delacroix himself captured the type in a painting entitled Torquato Tasso in the Hospital of Saint Anna, Ferrara (1824). In this painting Tasso, the sixteenth-century Italian poet and author of Jerusalem Liberated, an epic about the crusades, is confined to the madhouse. Tasso’s status as persecuted, misunderstood artist is implicit in the story told in a play by Goethe translated into French in 1823. The poet was locked up because of his love for the sister of the Duke of Ferrara. The type of the solitary genius is also expressed in Delacroix’s laterMichelangelo in his Studio(1849–50) and in his portrait of Paganini (1831) (see Plates 24 and 25), as well as in the work of one of the artist’s favourite writers, Byron:

To fly from, need not be to hate, mankind.

All are not fit with them to stir and toil,

Nor is it discontent to keep the mind

Deep in its fountain, lest it overboil

In the hot throng.

Click to see Plate 24: Eugène Delacroix, Michelangelo in his Studio

Click to see Plate 25: Eugène Delacroix, Portrait of Niccolò Paganini

Expressing one’s identity and inspiration was not simply, however, a matter of spontaneity, of (for example) dashes of paint transferring to the canvas an inner essence or soul. In a Romantic work, and contrary to the pronouncements of many critics, nothing could be so transparent, not even the identity of the artist. Think of that quintessential quality of the Byronic, the ‘secret language’ in which only special souls may share.

4.4 Revealing the inner being – exercise

Exercise 4

Read the following extract (dating from May 1824) from Delacroix’s journal. From 1822, following Rousseau’s tradition of self-confession, Delacroix kept a diary in which he expressed his views on himself and on his art. It was not published until 1893–5. What view does Delacroix express here about revealing one’s inner being in art?

What torments my soul is its loneliness. The more it expands among friends and the daily habits or pleasures, the more, it seems to me, it flees me and retires into its fortress. The poet who lives in solitude, but who produces much, is the one who enjoys those treasures we bear in our bosom, but which forsake us when we give ourselves to others. When one yields oneself completely to one’s soul, it opens itself completely to one, and then it is that the capricious thing allows one of the greatest of good fortunes … that of sympathizing with others, of studying itself, of painting itself constantly in its works, something that Byron and Rousseau have perhaps not noticed. I am not talking about mediocre people: for what is this rage, not only to write, but to be published? Outside of the happiness of being praised, there is that of addressing all souls that can understand yours, and so it comes to pass that all souls meet in your painting.

(Pach, 1938, p.89)

Discussion

An artist who ‘yields’ to his soul may express it in his art and hence communicate with other ‘souls that can understand yours’. This is, however, best achieved (paradoxically) from a position of solitude. (Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder had a similar insistence on the separation of aesthetic experience from everyday life.) Effective expression of one’s inner being is dependent on the adequate understanding of others.

4.5 The soul and sensitivity

In another journal entry of 1824, Delacroix speaks of the fact that the soul is inevitably trapped within the physical body:

It seems to me that the body may be the organization that tones down the soul, which is more universal, yet passes through the brain as through a rolling mill which hammers it and stamps it with the stamp of our insipid physical nature, and what weight is more insufferable than that of this living cadaver which we inhabit? Instead of dashing towards the objects of desire that it cannot grasp, nor even define, it spends the flashing instant of life submitting to the stupid situations into which this tyrant throws it. As a bad joke, doubtless, heaven has allowed us to view the sight of the world through this absurd window: its fieldglass, out of focus and lustreless, always turned in the same direction, spoils all the judgments of the other, whose native good faith is often corrupted and often horrible fruits are the result!

(Pach, 1938, p.93)

So far, then, we can see how Delacroix’s Romantic view of the artist as an elite soul was mediated by the ‘bad joke’ of his sensuality and physical weaknesses – ‘A link reluctant in a fleshly chain’ (Byron, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, Canto III, line lxxii). All of this might support the view that Sardanapalus is a sensuous riot entrapping (yet revealing to the initiated) the artist’s soul. But there was another force that Delacroix found to be of essential importance to the artist: intelligence or reason.

4.6 From Enlightenment to Romantic thinking

The Enlightenment had typically expressed, on the one hand, the soul and imagination and, on the other, reason and intelligence in terms of incompatible opposites. Not so Delacroix:

What are the soul and the intelligence when separated? The pleasure of naming and classifying is the fatal thing about men of learning. They are always overreaching themselves and spoiling their game in the eyes of those easy-going, fair-minded people who believe that nature is an impenetrable veil. I know very well that in order to agree about things, we must name them; but henceforth they are specified.

(Pach, 1938, pp.93–4)

The view that the world is essentially an ‘impenetrable veil’ rather than a composite of knowable, classifiable and understandable phenomena represents a key shift from Enlightenment to Romantic thinking. But note how, in this Romantic statement of belief in the world as an ‘impenetrable veil’ concealing a deeper reality and apparently defying rational understanding, Delacroix does not abandon the notion of intelligence or reason so dear to the Enlightenment. Rather, he incorporates it into the inseparable whole of his artistic identity. His intelligence fuses with his ‘soul’. The Romantics broke some of the boundaries and fixed categories which the Enlightenment had been keen to establish. In this case, it is significant that Delacroix sees intelligence as part of his innermost being, trapped, with his ‘soul’, within a physical body. In his paintings, therefore, we must expect some concealment of the self, imperfectly expressed through the sensuous and the physical and mediated by the workings of the intellect. No wonder he was so dismayed when viewers saw Sardanapalus as nothing more than an orgy of sex and violence: they showed no willingness to penetrate the ‘veil’, as it were. A sceptic in matters of religion, Delacroix held views on art that nevertheless assumed the existence of something beneath and beyond the purely material. And yet we must not forget the possibility that Delacroix’s journal may be, above all, a skilful work of self-presentation and self-justification.

5 Romantic themes and subjects in Delacroix’s art

5.1 Sardanapalus – a disconcerting subject

Many of Delacroix’s contemporaries found the subject matter of his Sardanapalus excessive and unpalatable. This was the opinion of an anonymous reviewer in the Moniteur Universel on 29 January 1828, who expressed the view that ‘the name [of Sardanapalus] has become synonymous with all that is most ridiculous and vile about debauchery and cowardice’. Furthermore, it was unlikely that ‘an effeminate prince should magically become a tactician and a warrior capable of defending Nineveh’ (quoted in Spector, 1974, p.80). Delacroix’s subject disturbed because it was the precise antithesis of classical heroism. Sardanapalus appears to be the ultimate anti-hero, world-weary, defeated, egotistical. Stendhal, while admiring Delacroix’s energy, was disturbed by the ‘satanism’ of the painting. Such interpretations were reinforced by, for example, the dark, hellish chasm at the bottom of the picture, which might be compared to the waters in the Barque of Dante. The painting shows an absolute ruler about to go up in flames with more than a lifetime’s provision of sex and violence. Here is no military hero or ruler offering a moral example, but a death scene worthy of Don Giovanni or the Marquis de Sade’s dying man. The moral clarity and certitudes of Neoclassicism, born of the Enlightenment and perpetuated in revolutionary ideology, have given way to a futile, self-defeating hedonism.

5.2 Sardanapalus – passion and futility

For many of Delacroix’s Romantic contemporaries, versed in Byronic despondency and melancholic ruminations on the futility and transitory nature of worldly pleasure, Sardanapalus expressed the condition of ennui, (melancholy or listlessness) – a kind of inner emptiness, languor, stultification and world-weariness. (The term ennui had been used in medieval French to signify profound sadness, disgust and personal anguish from the seventeenth century onwards it was used to describe a vaguer, less powerful form of melancholy or listlessness. SeeLe Robert, 2000, vol.I, p.745.) When painting his later Liberty Leading the People (Plate 29), which is discussed further below, Delacroix admitted that the hard work he did on it banished his ‘spleen’, another word used by the Romantics to suggest a lack of interest in life, or melancholy humour (see Johnson, 1981, p.130). (The word ‘spleen’ had been borrowed form English and was used by French writers from the eighteenth century onwards. It carried associations with the black humours or bile created by the bodily organ of the same name, attributed by the ancients with the power to create illness and melancholy. Like Faust, the artist fought against inertia and the temptations of nihilism. He confessed, in a journal entry of May 1824, that he needed to abandon reason and stir up his mind in order to satisfy its ‘black depth’. We might almost see Sardanapalus as reinforcing a Rousseauesque diatribe against luxury or acquisitiveness. While many Enlightenment thinkers (including Voltaire) had seen luxury as a sign of advanced civilisation, Rousseau had regarded it as a symbol of moral and social corruption and had urged a return to more natural, primitive values. In Byron's play, Sardanapalus refers to the prospect of being ‘purified by death from some/Of the gross stains of too material being’ (Gordon, 1970, p.491). We are reminded, also, of William Wilberforce’s criticism of ‘rapacity … venality … sensuality’. Apparently, then, the painting subverts the materialistic impulses behind the Royal Pavilion at Brighton and other sumptuous palaces. Delacroix’s particular Romantic sensibility is expressed as the denial of desire, or the searing realisation of the ultimate inadequacy of the material and the sensuous.

5.3 The popular Gothic

Most of the subjects Delacroix painted in the 1820s broke free from the constraints of the morally uplifting themes of the classical tradition, which had focused on the heroic and sacred achievements of ancient Greece and Rome or the saints and martyrs of Christianity. In the historical romances of Sir Walter Scott, the Gothic, medieval and anecdotal took the place of the grand, universal ideas that underpinned much classical art. There was a thriving private market for such subjects, which challenged the dominance in the Academy of classical history and culture. Legends, myths and tales were valued by the Romantics for their embodiment of valuable, imaginative truths. Delacroix was always proud of the daring approach he adopted in Sardanapalus – if saddened, ultimately, by the charge of defection from classicism uttered by those viewing it. He had written Gothic novels in his youth. His Gothic paintings, with their dark, looming architecture and horrifying events (as in The Murder of the Bishop of Liège), contrast with the order and decorum of David’s Neoclassicism; they liberated the artist’s imagination from an exhausted classical repertoire.

Indeed, a taste for the Gothic permeated French popular taste of the 1820s. Novellas and stage melodramas based on Gothic horror were in vogue. They frequently included stock figures of evil priests, monks and aristocrats: the Gothic was exploited as a means of social critique. In 1824 Delacroix made some caricature studies of priests and monks based on Goya’s Caprichos series (see Plate 26, Goya’s Theyre Hot, and Plates 26 and 28, sketches by Delacroix in similar vein). The plot of one of Delacroix’s own Gothic novellas, Alfred, concerns a corrupt priest who persuades an evil nobleman to force his son to take monastic vows so that the son’s inheritance may be easier to steal. Such plots were based on the darker side of Enlightenment literature, such as Diderot’s The Nun (written in 1760), a tale of Gothic suffering and forced convent vows. Gothic literature and art revelled in the extreme and the spectacular, in evil, ugliness and all manner of Faustian pacts with the devil. Sardanapalus, with its satanic destruction and horror, might be viewed as the archetypal Gothic melodrama.

Click to see Plate 26: Francisco de Goya, They’re Hot

Click to see Plate 27: Eugène Delacroix, Priests and Monks

Click to see Plate 28: Eugène Delacroix, sketch after Goya’s Caprichos

5.4 A taste for the grotesque

The grotesque was one aspect of this new aesthetic. The antithesis of the sublime and the beautiful, it was defined by Victor Hugo in his Preface to Cromwell:

In the thinking of the moderns … the grotesque plays a massive role. It is everywhere; on the one hand, it creates the deformed and the horrid; on the other, the comic and the farcical. It brings to religion thousands of original superstitious ideas and to poetry thousands of picturesque imaginings. It scatters and sows generously in air, water, earth and fire a myriad hybrid beings alive in popular medieval traditions; it is the grotesque that makes the terrifying circle of the [witches’] sabbath turn in the shadows, that gives Satan his horns, cloven hoofs and bat's wings. It is also the grotesque that … hurls into Christians’ hell those hideous figures later evoked by the grim genius of Dante and Milton … If it turns from the ideal to the real, it performs there inexhaustible parodies of humanity. The creations of its fantasy are those Scaramouches, Crispins and Harlequins [well-known comic types of the Commedia dell’Arte], grimacing shadows of men, types totally unknown to grave antiquity and yet originating in classical Italy [ancient Roman drama]. It is, finally, the grotesque that, adding colour, by turns, to the imaginative drama of both the south and the north, makes Sganarelle prance about Don Juan [in a comedy by the French seventeenth-century dramatist Molière], Mephistopheles around Faust.

(Hugo, 1949, p.27; trans. Walsh)

The ‘picturesque imaginings’ of the grotesque recall both the intense, hybrid interiors of Brighton Pavilion and the nightmare experiences recounted by Thomas De Quincey.

5.5 The Gothic, the grotesque and artistic expression

The Gothic and the grotesque replaced classical reason, order and regularity with the irrational, the irregular and the deformed. Delacroix was drawn to them as a means of breathing new life into artistic expression. He was attracted to English and German literature, particularly Shakespeare and Goethe – because, to the unified, clearly defined aesthetic categories of the classical, they opposed the fractured and hybrid genres less susceptible to categorisation of any kind. Shakespeare mixed tragedy with comedy, and both he and Goethe, in some of their work at least, mixed beauty with the grotesque. The term ‘grotesque’ had originated as a means of describing the ornamentation discovered, during the Renaissance, in Roman grottoes. Originally it was coined in connection with ornate, fantasy figures, a mix of the real and the imaginary. To the enlightened, neoclassical architect Robert Adam, the grotesque was ‘that beautiful light stile of ornament used by the ancient Romans, in the decoration of their palaces, baths and villas’ (from The Works in Architecture of Robert and James Adam, Esquires (1778–1822), quoted in Eliot and Whitlock, 1992, vol.I, p.228) – in other words, a source of elegance. Then the term acquired connotations of the extravagant or ridiculous. Hugo meant by it anything strange, monstrous, ridiculous, comic, deformed, physically or morally ugly. To the Romantics of Delacroix’s generation, the grotesque allowed them to cross traditional boundaries of the comic and the tragic in a way reminiscent of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, a hybrid made up of opera seria and opera buffa. Its mix of the real and the theatrical, the extravagant and the serious also recalls the Gothic, neoclassical and exotic hybridity of the Royal Pavilion at Brighton, although this building (along with the equally heterodox poem Lallah Rookh by Thomas Moore) lacked the dark, satanic overtones often incorporated into the grotesque by French Romantics.

5.6 Modernity – challenging tradition

Delacroix also challenged tradition in paintings like Greece on the Ruins of Missolonghi (1826) and Liberty Leading the People (1830) (Plates 29 and 30), in which he mixes conventional, classical allegory with realism: the leading women in these paintings are both antique ideal and fleshy reality. (This rejection of traditional boundaries and categories was a hallmark of the Romantic mindset.) Greece on the Ruins of Missolonghi commemorates the death in 1824 of Byron at Missolonghi. Byron had travelled there in order to assist and finance Greek insurgents against Turkish rule, but died after contracting a fever. In 1825 the Turks defeated the Greeks and recaptured Missolonghi; the Greeks blew themselves up rather than surrender. (The independence of Greece was finally recognised in 1829.) In the painting, the woman personifying Greece, standing in front of a triumphant Turk, is at once classical allegory and real woman dressed in national costume. Delacroix has adapted classical conventions to his own requirements. The same adaptation occurs in Liberty Leading the People, in which the allegorical heroine leads the masses in the 1830 revolution discussed later.