Composition and improvisation in cross-cultural perspective

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 16 April 2024, 6:59 AM

Composition and improvisation in cross-cultural perspective

Introduction

This course explores two important concepts relating to the creation of music, namely composition and improvisation. The concepts of composition and improvisation are closely linked, and the reason for looking at non-Western music is partly to demonstrate this truth – it should help to clarify these two concepts, and the relationship between them.

We couldn't hope to cover a representative sample of the world's musics in a single course, and I have certainly not tried to do so here. What I have tried to do instead is two things: to introduce two Asian music traditions in enough detail to give you an idea both of what they can sound like and of how they work; and to introduce some general issues to do with the concepts of composition and improvisation, which will be relevant to all music. There is a lot of material to cover in this course, including about an hour of video, which I will be asking you to work through in some detail. Although you will be working closely on the detailed structure of the musics that I introduce in the case studies, you will not need to remember everything in detail. You will need to understand and remember the underlying principles, however.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of Level 3 study in Arts and Humanities.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

discuss different perspectives on the creation of music, in particular, composition and improvisation

understand the basic principles underlying North Indian art music

understand the basic principles underlying Sundanese gamelan music.

1 The creation of music

1.1 Composition and improvisation in the world's musics

I want to begin with some general issues. Since the words composition and improvisation will play an important role in this chapter, where better to start than with definitions of these two terms?

Activity 1

What do the concepts composition and improvisation mean to you? How do they differ? Note down your thoughts, along with some examples of composed and improvised musics.

Discussion

I wonder how close your definitions are to those given in the New Grove Dictionary? The first sentence of each is given below. (These extracts do not do full justice to the complete entries, which you may be interested in looking up.)

Composition: a piece of music embodied in written form or the process by which composers create such pieces.

Improvisation: the creation of a musical work, or the final form of a musical work, as it is being performed.

(New Grove, ‘Composition’ entry, p. 599; ‘Improvisation’ entry, p. 31)

These sentences, brief as they are, suggest a couple of differences between these concepts which you might also have thought of. First, this definition of composition features the word written: a composition is, to most of us, a piece of music committed to notation. Secondly, the definition of improvisation stresses the creation of music ‘as it is being performed’: according to this view improvisation is instant and doesn't allow much time for consideration (let alone notation).

If we elaborate these two points, a picture emerges of two quite different scenarios. The composer writes music down, taking his/her time, sketching and revising until the music is as near perfect as it can be. The improviser creates music instantly, without sketches or corrections. In the words of Willi Apel, an earlier dictionary editor, improvisation is ‘the art of performing music as an immediate reproduction of simultaneous mental processes, that is, without the aid of manuscript, sketches or memory’ (Harvard Dictionary, pp. 351–2).

As examples of composed and improvised musics you might have thought of some of the following: for composed music, most Western art music; as improvised music, jazz and, perhaps, one or more non-Western traditions such as Indian art music. By the end of this free course you will have had an opportunity to think about these assumptions and to re-assess them. The idea, for instance, that Western music is exclusively composed is rather an exaggeration: there are numerous examples of improvisation in our art music tradition. The common view that most non-Western musics are improvised is even more dubious, especially if we accept Apel's definition of the term. As the ethnomusicologist Mantle Hood claimed in response to Apel:

If, by definition, the processes of improvisation are devoid of manuscript, sketches or memory, then I must conclude either that I have never heard or witnessed improvisation or that such processes simply do not exist.

(Hood, 1975, p. 25)

The fact is, most of us don't actually know very much about improvisation. To many students and practitioners of Western art music, improvisation is a foreign concept. Jazz (or Indian, African or other music) can be a puzzle, dismissed by some as a lesser art and accepted by others only as some kind of unfathomable mystery. When we hear a piece of Indian music, and say that the musicians must be great improvisers to produce such music without a score, perhaps we are really saying that we don't know how they do it. What will emerge as this chapter progresses is that the more we find out about ‘how they do it’, the more inadequate our concepts of composition and improvisation become.

1.2 Different perspectives on the creation of music

If a simple division into composition and improvisation is not going to be adequate, particularly when considering music beyond the Western art tradition, then what can we usefully say about the different ways in which music is created? A starting point might be to remind ourselves of the similarities between composition and improvisation. Both the improviser and the composer create music. Both of them, in doing so, draw on a range of skills and experience: their musical training and knowledge of music theory, the repertoire they have learned, vocal or instrumental technique, and so on. No one, composer or improviser, has ever created music out of nothing, without reference to what has gone before. Both improviser and composer build up a store of musical experience before creating something new, and that ‘something new’ is both related to and in some way different from what has gone before. Beethoven drew on the tradition handed down to him, arguably neither more nor less than did jazz saxophonist John Coltrane or Indian sitarist Pandit Ravi Shankar.

In an important sense then, composition and improvisation are aspects of the same phenomenon rather than opposed concepts. They appear to be very different, and often they can be treated as such, in Western music at least, because in this case we can often make a distinction between the notes the composer put on the page, and those details left for the performer to decide. Applied to other musical traditions however, the distinction rarely applies in a comparable way.

What, then, distinguishes different types of musical creation? Two factors we have already considered are the use of notation and the time-scale involved, and these bear further examination.

Notation is certainly an important factor (for one thing it can impose a longer time-scale on the creation process, since the act of writing down music is in itself time-consuming). In fact, many people talk of another dichotomy, related to but distinct from that between composition and improvisation: that between music in notational traditions (written music) and that in oral traditions (unwritten music). This is an important distinction, because the use of notation in teaching and performance has many important implications. Historically, since notation was the first means by which European art music was turned into a tangible artefact, it made it easier for people to conceive of a piece of music as an object (equivalent to a painting perhaps). Notation therefore played a part in the emergence of ideas of the ‘musical masterpiece’, and of the ‘great composer’. Conventional notation usually enables particular pieces of music to be preserved indefinitely, unchanged, whereas unwritten music tends to change gradually over time. And, perhaps paradoxically, notation can also enable music to change more rapidly than it does in oral traditions. It is difficult for an avant-garde composer to make an impact without the medium of notation through which to spread his work, so it tends to be written music which generates radical departures from tradition (recordings have helped to support similar processes in other traditions, notably jazz).

All written music is, by definition, composed. Remember, however, that composers can and in most cases must leave some decisions for performers to make – an exception to this would be the case of a composer who also produces and records the definitive performance of his/her work, for instance through electronic means. Is it true, though, that all unwritten music is improvised? Apparently not. Numerous examples around the world demonstrate that much may be composed, taught and performed without the use of notation. So although the distinction between written and unwritten music is important, it should not be confused with that between composed and improvised music. The terms ‘written’ and ‘composed’ overlap, but are not synonymous.

What then of the point about time-scales? Is there a distinction between music which is thought out in advance, and perhaps performed a considerable period of time after its completion, and that which is conceived and performed almost at the same moment? At least one authority on the subject, ethnomusicologist Bruno Nettl, thinks so:

We could speculate upon the division of the world's musical cultures and of their subsystems – genres, periods, composers – into two groups. One of these would be the music which is carefully thought out, perhaps even worked over with a conscious view to introducing innovation from piece to piece and even from phrase to phrase: the other, that which is spontaneous but model-bound, rapidly created, and simply conceived. The first gives up spontaneity for deliberation, while the second eschews a search for innovation in favour of giving way to sudden impulse. Neither need be considered improvisation …

(Nettl, 1974, p. 11)

You might have found Nettl's last sentence slightly confusing: surely the two categories he describes (the consciously worked out, and the spontaneous) correspond to composition and improvisation respectively? Not exactly – Nettl would put much so-called ‘improvised’ music in the same category as rapidly-composed written music, as this next passage makes clear.

Schubert is said to have composed a song while waiting to be served at a restaurant, quickly writing it on the back of the menu; Mozart turned out some of his serenades and sonatas almost overnight; and Theodore Last Star, a Blackfoot Indian, had visions in which, in the space of a minute or two, he learned from a guardian spirit a new song. But, then, Brahms labored for years on his first symphony; Beethoven planned and sketched ideas for his Ninth over two decades; and William Shakespeare, an Arapaho Indian, said that when he took a bit from one song, something from another, and a phrase from a third, making up a new Peyote song, it might take him a good part of an afternoon.

(Nettl, 1983, p. 26).

This all raises the question: how should we define composition and improvisation? We haven't yet, however, reached the point where we can answer that question.

1.3 Studying unwritten musics

I want to move now from concerns relevant to all music to those more relevant to the study of unwritten musics in particular. One of the biggest distinctions between the European art tradition and most others is in the use of notation, which musicians in the former use more extensively than those anywhere else. Although music notation is used in many other traditions, particularly within Asian art musics where it has a long history (for example, the earliest surviving written musical notation in India dates from c.500 AD at the latest; written notation was also in use in China by this time (Widdess, 1995, pp. 4, 90; New Harvard, p. 547)), it is the case that very few non-Western traditions use notation in anything like the way Western art music does. In most cases where notation exists (as in India, for example), it is used only to keep an additional record of music which is memorised, working as a kind of insurance policy. This notation is not used to teach music, and nor is it referred to in performance. To a great extent then the study of music outside the Western art tradition is the study of music which involves either a very limited use of notation or no notation at all – in effect, unwritten music.

As I suggested above, we can't assume that unwritten music is improvised. Indeed, when studying unwritten music, establishing the division between the composed and the improvised becomes virtually impossible. As psychologist Jeff Pressing asks (rhetorically), ‘since no action can be completely free of the effects of previous training, how does one reliably distinguish learned from improvised behaviour?’ (Pressing, 1984, p. 345). The answer is that we cannot; we need to side-step the term ‘improvisation’, and instead ask simple questions like how does the music work, and how is it structured?

1.4 Models and building blocks

When any musicians perform they refer to something pre-existent, something we might call a ‘model’ or ‘referent’. For musicians performing written music, the most important of these (although not necessarily the only one) is the score or part from which they perform. Depending on the particular genre and period in question, the performer may have freedom to choose or alter certain parameters (tempo, dynamics, phrasing, in some cases the notes themselves), but the score will indicate, to a very great extent, what to play. For musicians in unwritten traditions too, some sort of model will always exist. The music may be based on a particular scale or mode; it may involve a specific metre or a repeated rhythmic pattern; it may be based on a text which must be sung or recited; or it may involve particular processes (e.g. the music must speed up or get louder or more complex). In some cases it doesn't matter what melodic phrases are played, so long as they are based on a particular scale, or relate to a certain harmonic progression. In other cases the outline or contour of the melodic phrases may be fixed, but the details of their ornamentation not. The possibilities are endless, but all kinds of music have this in common – that certain things are prescribed or fixed, and others not.

According to this interpretation, perhaps the closest parallel to the conventional composition-improvisation dichotomy is a distinction between music with a relatively high density of fixed elements, and that with a low density (first suggested by Nettl, 1974, pp. 12–13). Most Western art music has a relatively high density of such fixed elements, since both the notes to be used and their relative durations are prescribed; many non-Western traditions have a relatively low density, although this fact is often difficult for outsiders to determine without extensive research.

The term ‘fixed element’ suggests the existence of formal constraints (i.e. that something must occur at a particular point in the performance). In some cases, it may be more relevant to talk about ‘building blocks’: where, for example, the music is limited to set melodic phrases or rhythms which may be combined in numerous ways. Whether we talk of building blocks, fixed elements or obligatory features, they can all be thought of as different kinds of ‘model’. A model in this context can be any kind of guide the performer uses to construct music, whether highly detailed (as in most kinds of score, especially of ensemble music) or much less so (‘Play what you like as long as you stick to G major and 4/4’). In a little while, we'll be looking at the kinds of models used in the performance of Indian art music.

1.5 The limits of memory

In unwritten music, a factor which places a constraint on the number of fixed elements – the degree of detail specified by any model – is memory. Whatever is fixed must be memorised; as a matter of necessity, therefore, performers in these traditions have evolved strategies which limit the load placed on their memories. Here is Nettl again:

Dividing music into elements, I hypothesise the need for some of these to remain simple, repetitive, stable, so that others may vary. There is probably some point beyond which it is impossible for any sizeable population of musicians to remember material … Recurring events or sign posts such as motifs or rhythmic patterns, conciseness of form, brevity, or systematic variation may, as it were, hold an aurally transmitted piece intact.

(Nettl, 1983, p. 192)

We shouldn't underestimate the ability of musicians to memorise pieces of considerable length and complexity. In the West for instance, pianists often perform lengthy concerts entirely from memory. It should not be surprising that musicians who never use notation may tend to develop even greater powers of memorisation than those who do. Nevertheless, there is always a limit. Indian maestros who perform without notation, for three hours or more each night (and the music different each time), are not reproducing memorised performances. So how do they do it?

One way of answering this question is Nettl's: certain aspects of music remain stable or repetitive so that others can vary. Another, complementary, approach is to say that musicians have to learn and memorise two types of information: the models, and the ways of turning those models into music. The jazz soloist, for instance, learns a stock of songs and compositions, as well as ways of generating solos appropriate for those pieces and his/her instrument. Similarly, in any unwritten music tradition, performers learn models for music-making (scales, modes, melodies; rhythms, metres; harmonies; song texts; and so on), and they also learn how to turn those models into acceptable performances.

1.6 Summary

You may find it useful to go over the main points of the first section again.

We in the West generally recognise two different concepts of musical creation, namely composition and improvisation. Composition is widely characterised as a relatively lengthy process involving the use of notation; improvisation involves the spontaneous generation of music without notation. The distinction can be useful when applied to our own art music tradition.

Looking at music from a global perspective, however, this dichotomy appears very simplistic and is rarely of use. Insofar as the concepts are useful at all, they can be regarded as two complementary aspects of the same phenomenon: the creation (or, indeed, composition) of music.

There are, however, various points of difference between different types of musical creation. These include the use of notation, the time scale and degree of conscious planning involved.

Most kinds of musical creation involve the interaction of models (comprising certain fixed elements) with variable elements. Composers and performers alike must learn the models as well as the rules or procedures involved in controlling variable elements.

When we study musical creation, whether we call it composition or improvisation, we can consider both the nature of the models used and the ways in which they are turned into actual performances.

2 A performance of North Indian art music

2.1 An introduction to khyal singing

I now want to move on to explore the first of two case studies of non-Western music-traditions: North Indian art music, also known as Hindustani music. (There are two major art music traditions in South Asia; the other is known as South Indian or Carnatic.) In this section I will take you through a performance of music from this tradition and consider some of the questions posed by Section 1: how is this music put together? To what extent is it composed in advance, thought out, sketched and revised; and to what extent is it created in performance? Is notation used, and if so, how? How might we describe the models for the performance? Which elements are fixed, stable or repetitive? Which elements are variable and determined in performance, and what guides the performer in making the necessary decisions?

I want to cover a lot of these questions through the use of video clips, which include performance footage, demonstrations by the performer, and extracts from a teaching session. Before you watch the video, however, a little background information will be useful.

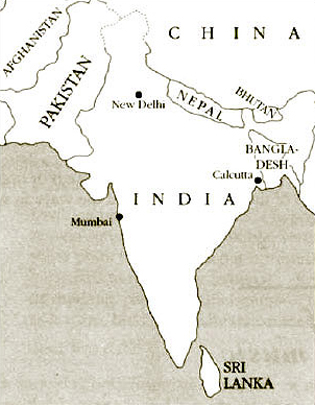

The North Indian art music tradition is practised widely over northern and central India, Pakistan and Bangladesh (see Figure 1). It is also quite well known beyond this native area: you may have heard, or at least heard of, leading performers such as the sitarist Pandit Ravi Shankar. It is an art music tradition, comparable in some respects to that of the West. Court and religious contexts have played an important role in its development, while in the present day its largest audience is to be found among the middle-class population in the towns and cities.

Figure 1

The tradition includes a number of related styles and genres, both vocal and instrumental. The piece featured in the video belongs to a genre called khyal , which is the most commonly heard vocal genre in the tradition (although not by any means the only one). Khyal performances can vary widely in style, textual content, accompaniment and other aspects. (Khyal is a word of Persian origin, meaning literally ‘imagination’ or ‘fancy’.) This section is not intended as a survey of, or introduction to, Indian music as a whole, but is a detailed case study of a single performance. This particular performance is typical of the khyal genre, but not everything that happens here happens in all performances, and conversely some features common in other styles are not represented here.

In order to address the issues which concern us here we will have to go into some of the technicalities of the music and introduce some unfamiliar terminology. You will not need to remember all the details.

Like most performances of North Indian art music, this one features a soloist assisted by a group of accompanists. Typically for khyal, the singer is accompanied by one or more players of the drone-producing lute called tanpura; a drum set called tabla; and a melodic accompanying instrument, in this case a harmonium. The role of these different instruments should become clear in the course of the video. They are essentially at the disposal of the soloist, who instructs the musicians what to play, when and how – although subservient in this respect, they are nevertheless often fine musicians in their own right. (Note that ‘lute’ is used here as a generic term for a class of stringed instrument; technically, it covers those with separate neck and resonator, whose strings run parallel to the sound table.)

The soloist featured in the video clips is Veena Sahasrabuddhe, one of the leading performers of the khyal genre. She will take you through a performance of Rag Rageshree (i.e. a rag or mode, by the name of Rageshree). This piece moves through a number of distinct stages, of which some of the most important are described and demonstrated in the video. In each case, after this explanation, you will see a corresponding extract from the final public performance itself. Finally, the video shows the whole public performance. After you have studied the clips for this case study, you should be familiar, at least in general terms, with the following points.

What is meant by the term rag (mode, melodic framework), and what Rag Rageshree sounds like (we will not, however, be analysing the rag itself in any detail).

What is meant by the term tal (metre, rhythmic cycle), the particular tal used here (called jhaptal), and how it regulates the music.

The way the performance moves through different stages, and the kind of techniques employed by the soloist.

You do not need to memorise all the close detail covered by the video.

Activity 2

In a moment I shall ask you to watch the first sections of the video. Below is a list of the technical terms that are used and explained in the video, laid out in the order in which they occur, so that you can find them easily. For some I have added explanations, which may include additional information not on the video. The others are the names of the stages in the performance I mentioned above.

As you watch the video clips, I want you to use the list of terms for two activities.

Listen out for mention of the terms listed. Pause the video and read my notes as each term is mentioned, to ensure you understand the term and how it is used.

In the places where I have not supplied notes about the stages listed, listen to the explanation that is given on the video, and then pause the video and make your own notes based on the information you have heard, answering the following questions in each case.

(a) Is this stage sung with, or without, drum accompaniment?

(b) Is it sung to a particular text, or if not how is it vocalised?

(c) How would you describe the rhythmic and melodic style (i.e. fast or slow, free or strict, flowing or broken, etc.)?

Now watch the masterclass in the video clips below, following my list of terms and pausing to read and make notes where appropriate.

Veena Sahasrabuddhe sings Rag Rageshree part 1 [8 minutes 40 seconds 23.3MB]

Veena Sahasrabuddhe sings Rag Rageshree part 2 [9 minutes 54 seconds 26.7MB]

Veena Sahasrabuddhe sings Rag Rageshree part 3 [4 minutes 6 seconds 11MB]

| barhat | The ‘development’ of a piece, translated loosely here as ‘improvisation’; barhat means, literally, ‘increase; growth’. |

| aroh-avaroh | Basic ascending and descending lines of a rag. |

| alap | |

| sargam | Singing to the abbreviated note names (i.e. instead of a meaningful text); these are, in ascending order, sa, re, ga, ma, pa, dha and ni. (Note: you will not hear the name of the fifth note pa in this example. This note is not used in Rag Rageshree, which is hexatonic.) Veena Sahasrabuddhe is using sargam here as a teaching device – she instructs her pupil to repeat the melody ‘in alap’, by which she means singing to the vowel ‘aah’. |

| bandish | |

| tal | Metre, i.e. that which regulates the rhythm. |

| jhaptal | A particular tal. Jhaptal has a ten-beat pattern which is repeated indefinitely. |

| bhav | Mood, emotion, meaning. |

| bol alap | |

| bahlava | |

| tan |

Answer

Here are my notes for the different stages. I hope you got at least some of these points, although you may not have got them all. (I have separated comments on rhythm and melodic style, although these are closely related.)

| alap | sung without drum accompaniment; no text (uses vowel sounds, such as ‘aah’); |

| slow tempo, rhythmically free; | |

| a mixture of long and short phrases; | |

| flowing melody with lots of portamento, melisma, ornamentation etc. | |

| bandish | sung with drum accompaniment; |

| sung to a text; | |

| medium tempo, strict rhythm; | |

| slightly simpler melodic line than alap. | |

| bol alap | sung with drum accompaniment; |

| sung to a text; | |

| medium tempo; | |

| fairly free rhythm. | |

| bahlava | sung with drum accompaniment; |

| medium tempo; | |

| very long, continuous, flowing and rhythmically loose melodic lines. | |

| tan | sung with drum accompaniment; |

| no text (vowels); | |

| fast tempo (especially in the performance footage); | |

| long, continuous melodic lines. |

Activity 3 (Optional)

The next section of video clips shows the complete concert performance of the Rag Rageshree. This section lasts for a total of 25 minutes. If you have time, you will find it useful to watch it now to consolidate your understanding of the characteristics of the different stages of the piece and how they fit together in a single ultimate performance; if you do not have time to watch it all now, come back to it later as a revision exercise.

As you watch, the timings chart in Figure 2 below will help you to keep your bearings and follow what is going on. The captions on the video will also help to identify the stages of the piece.

| Time (mins) | Section | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part 1 | 0 | Alap | |

| 1 | |||

| 2 | |||

| 3 | Bandish - first part | ||

| 4 | |||

| 5 | Bol alap | ||

| 6 | |||

| 7 | Bahlava | ||

| Part 2 | 8 | ||

| 9 | |||

| 10 | |||

| 11 | Bandish - second part (antara), which emphasizes the upper tonic ('sa') | ||

| 12 | |||

| 13 | Bol alap based on antara (second part of bandish) | ||

| 14 | |||

| 15 | Sargam | ||

| 16 | Bol alap | ||

| 17 | |||

| Part 3 | 18 | Tan | |

| 19 | Bol tan (tan sung to words) | ||

| 20 | |||

| 21 | Tan | ||

| 22 | Tarana (wordless composition set to a different rythmic cycle) | ||

| 23 | |||

| 24 | |||

| 25 |

As you watch, make notes in answer to the following questions. How would you describe the organisation of the performance as a whole? Why do you think these stages come in the order they do?

Veena Sahasrabuddhe performs Rag Rageshree part 1 [7 minutes 40 seconds 20.8 MB]

Veena Sahasrabuddhe performs Rag Rageshree part 2 [10 minutes 9 seconds 27.7MB]

Veena Sahasrabuddhe performs Rag Rageshree part 3 [7 minutes 53 seconds 21.5MB]

Answer

You should have noticed certain tendencies as the music moves from one stage to another.

It moves from singing without drum accompaniment to singing with the drums (tabla). As the drums are introduced, the music changes from unmetred to metred (in this tradition, metred sections are always accompanied by drums).

Although the transition is not entirely smooth, the rhythm is much more regular at the end than at the beginning.

Rhythm and tempo are much faster at the end than at the beginning.

We move from singing without text, to with text, and back again.

We may surmise that the different stages occur in this particular order so as to allow (or to bring about) a transition from unmetred, unaccompanied, slow and rhythmically free singing to that which is metred, accompanied, fast and rhythmically strict. Similar processes occur in many other kinds of music – the transition from recitative to aria in opera being one example (the difference here, of course, is that recitative and aria alternate, whereas the shift occurs only once in this Indian performance).

Some additional points that may not have been immediately obvious from the video are to do with the division between which aspects of the music are rehearsed and decided beforehand, and which are directed by Veena Sahasrabuddhe as the concert performance takes place. Basically, the students know from rehearsal that they will be required to sing during refrains of the bandish (which they will have learned), and keep quiet while she is singing alap, bol alap, bahlava and tan. If she wants them to sing up or quieten down in the performance, she gestures appropriately. The pace is set by Veena Sahasrabuddhe too: she indicates this by tapping her hand at the beginning, and when an acceleration is required.

2.2 Notation

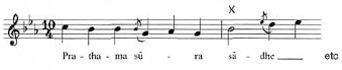

The next thing to consider is the role of notation in this tradition. At one point on the video you saw Veena Sahasrabuddhe singing from a printed notation, from a collection first published in the first quarter of the twentieth century by the famous Indian musicologist Pt V.N. Bhatkhande (originally in the Marathi language, this is now best know in its Hindi translation in volume 5 of Bhatkhande, 1987). Actually, she did this at our request – she would not normally sing from notation, but did so to enable us to compare different versions of the bandish (composition). What will not have been clear is the relationship of the information in this printed notation itself to (a) what she actually sings ‘from’ the notation; and (b) what she sings in her own demonstration and performance of the same piece, without reference to the notation but drawing instead on her own knowledge of the piece. To clarify this, I have transcribed the first line of each of these into staff notation in Examples 1, 2 and 3 below. In order to follow the notations you will need to know:

that the three-flats ‘key signature’ does not indicate a Western-style key. B♭ is in fact the ‘key note’ (the main note we hear in the drone); the scale is hexatonic, with no fifth and a flat seventh (notated here: B♭ C D E♭ G A♭).

the 10-beat metre jhaptal is indicated for our purposes by a 10/4 time signature. The single bar line and the symbol ‘X’ indicate the beginning of the cyclical pattern (X marks beat 1; thus, counting back, you will find that the first version starts on beat 5).

Example 1: Printed notation (after V.N. Bhatkhande)

Example 2: Transcription of what Veena Sahasrabuddhe actually sang from the printed notation for demonstration purposes.

Example 3: How Veena Sahasrabuddhe sang the same phrase in performance, without reference to the notation.

Activity 4

Compare the notations in Examples 1 and 2 (above). How you would describe the relationship between the printed version and version sung from it? What does this suggest about the status of notation in this tradition?

Answer

We can say that the printed version (Example 1) is simpler than even that sung from the notation (Example 2). To put this another way, the notated version is like a skeleton which is ‘fleshed out’ by the performer by the addition of subtle ornamentation. More striking still, in a couple of cases Veena Sahasrabuddhe actually sings a different note from that printed. This suggests that the importance of the notation is quite low: Veena Sahasrabuddhe does not feel constrained by it, and is confident that her own version is at least as authoritative as that printed.

These observations are backed up by a couple of other things on the video. First, Veena Sahasrabuddhe and her accompanists are not performing from notation. Secondly, in her explanations she clearly attributes little importance to notation: it is a means of preserving compositions (bandishes) as an insurance against failures of memory, and for this purpose audio recordings nowadays do a much more efficient job (since any refreshing of memory would be done well before a public performance). In fact, as she states in the video, Veena Sahasrabuddhe learned this composition from her father: this would have been a process of imitation and memorisation; in other words, oral transmission. Although she is aware of the existence of a notated version, she does not consider it authoritative. For instance, when she and I were collaborating on a translation of the song text, she pointed out to me that the version printed was in fact incorrect in several details (i.e. she considered the version she had learned orally to be the authoritative version).

2.3 Conclusion

As I warned you, it has been necessary to introduce here a fair amount of technical detail on North Indian music. You will not need to remember all of this – indeed, apart from a little basic terminology (such as rag and tal), some instrument names (tabla, tanpura) and the name of this genre (khyal), you may not come across any of these terms again in this course. What I hope you will remember is what this has taught you about the way North Indian art music is put together, and what this tells us about composition and improvisation.

First, here is a list of things you should have picked up about North Indian art music, and the khyal genre in particular.

This music is not performed from a score. Although notations do exist, only a small part of what is performed is notated (the bandish), and even that in a very skeletal fashion. Notation is little used, and has little or no authority.

The performer memorises a certain amount of material: the bandish (i.e. the basic setting of the text) and the rag and tal. (I don't expect you to have picked up the details of these, but it should be clear that melody and rhythm are regulated in some way.) These might be described as the ‘building blocks’ of the music.

Using this learned material, the artist constructs a performance. He or she is guided by certain basic principles (the transition from unmetred, slow, rhythmically free music to that which is metred, fast and regular): within this overall plan various specific techniques or processes (bol alap, bahlava, tan etc.) are accommodated. We could describe this as a kind of loose formal ‘model’ for the construction of a performance.

Both the overall formal plan and the specific techniques used are defined in such a way as to allow an infinite number of equally valid, and equally authoritative, performances.

Accompanists know what is expected of them, to a great extent, from their own training. The soloist retains overall control of the performance, however, and can signal any changes required (e.g. acceleration).

3 A performance of Sundanese gamelan music

3.1 An introduction to gamelan music

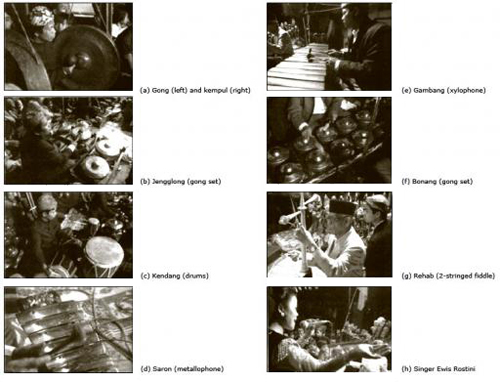

The previous section introduced you to a music tradition which places great demands on the inventiveness and virtuosity of a single individual. Although this individual is supported by accompanists, it is to a large extent a soloistic music. We will now move on to a very different kind of music, in a tradition which places more emphasis on group interaction and ensemble playing. This is gamelan music of Sunda, an area comprising roughly the western third of the island of Java, in Indonesia (see Figure 3). Once again this section will concentrate on a particular piece rather than trying to give an overview of gamelan music. As before, you will be introduced to the music through video, and once again a little background information will first be useful.

3.1.1 Background information

Gamelan is the name given to a number of related musical ensembles in Indonesia. These ensembles comprise various types of instruments, the majority made of metal and most struck with beaters. There are several gamelan traditions, of which three are particularly well-known. These three are, moving from east to west, the Balinese, Javanese and Sundanese gamelans. (The term Javanese gamelan normally refers to the tradition developed in central Java; the Sundanese, who occupy the western part of the same island, consider themselves culturally distinct from the Javanese rather as the Scots are distinguished from the English.)

Most gamelan music is performed without the aid of notation, yet involves the co-ordination of many parts, which interlock and overlap in a variety of ways. The obvious question is, therefore, how can the members of the group keep together and produce coherent music, without either playing from notation or memorising impossibly large amounts of music?

3.2 Parts of the gamelan salendro

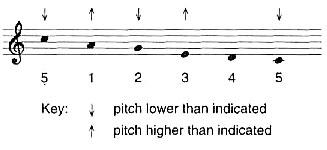

The next set of video sequences feature a type of Sundanese ensemble called gamelan salendro. You will need to know that this music is based on a pentatonic scale, also called salendro. The Sundanese use various methods to describe this scale, the simplest of which is a numerical system in which each note of the scale is assigned a number from 1 to 5. One aspect of the system which may take a bit of getting used to is that the Sundanese assign the numbers to a descending scale, so that pitch 1 is higher than pitch 2 and so on. Similarly confusing is the fact that pitches in the higher octave are indicated by a dot beneath the number, and those in the lower octave by a dot above. The scale is roughly equidistant, with pitch 1 approximately equivalent to A in the Western scale. I have written out the scale in Example 4, below, in staff notation, although in fact you may find it easier to simply follow the number notations than to ‘translate’ everything to and from Western terms. (Note: in a truly equidistant pentatonic scale, each interval would be 2.4 semitones – that is, 240 cents, where one semitone = 100 cents.)

Example 4

Activity 5

Watch the video clip below, which introduces the sights and sounds of the Sundanese gamelan salendro to give you an idea of the music.

Sudanese gamelan part 1 [1 minute 7 seconds 3.01MB]

The next section of the video, headed ‘Instrumental parts for the piece “Bendrong”’, takes you through a few of the simpler instrumental parts for this piece. For the first two instruments featured – the gong and jengglong – I would like you to try to work out the repeated pattern of notes played in each case, and the next activity asks you to do this. You may need to replay the relevant sections of the video several times to complete the activity. As we work through the various instrumental parts you will gradually see how the structure of the piece works, with overlapping instrumental parts working together to build up the overall sound.

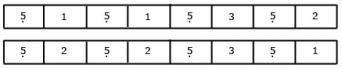

Activity 6: The gong part

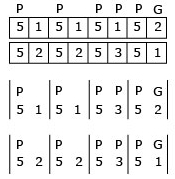

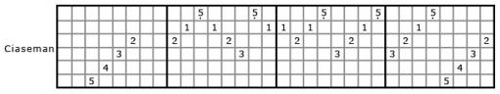

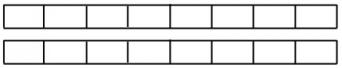

The gong player plays a repeated pattern of notes in an 8-beat cycle, using two gongs called the kempul and gong, as demonstrated and identified on the section of video that you are about to watch.

The grid below shows a space for each beat of the cycle. Watch the video and note whether the kempul (‘P’) or the gong (G) is played on each beat. Leave the space empty if there is a rest with neither instrument playing on a particular beat. Wait for the indication on the screen to help you identify the first beat of the cycle before you begin. (Note: Many Indonesian nouns begin with the prefix ‘ke’ or ‘kern’ so this prefix is generally ignored in abbreviations, to avoid confusion: hence the use of ‘P’ for ‘kempul’.)

![]()

Watch the video clip below featuring the gong player now.

Instrumental part for the bendrong [1 minute 7 seconds 3.10MB]

Answer

This is how the grid should look. If this is not what you got, watch the video again and try to relate what you see and hear to what is written below.

![]()

Actvity 7: The jengglong part

The jengglong is a set of smaller pitched percussion instruments (sometimes called ‘kettle gongs’). Again you will see that the performer on the video plays them in a set sequence – or, rather, in two alternating sequences, which I would like you to listen to carefully and note down on a grid (see the example below)with two rows for both cycles. (It doesn't matter which one you put first, since they alternate repeatedly.)

As you watch, the video graphics will help you to identify the first beat of the 8-beat cycle, and will also identify the note name in the form of a pitch number for each instalment.

Watch the video clip below demonstrating the jengglong part now, and fill in the appropriate pitch number for each beat in your grid.

Instrumental part for the jengglong [1 minute 48 seconds 4.86MB]

Answer

I hope you got the following answer. (You could have the two lines the other way around; it doesn't matter.) If this is not what you got, watch and listen again, trying to match what is on the video to my answer.

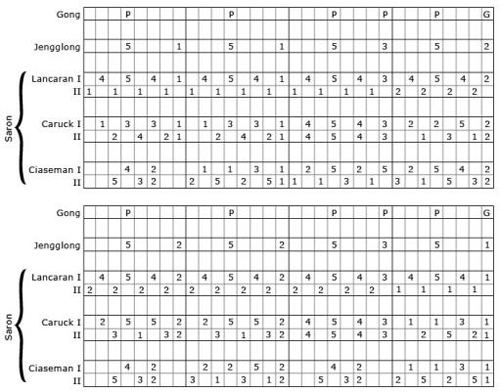

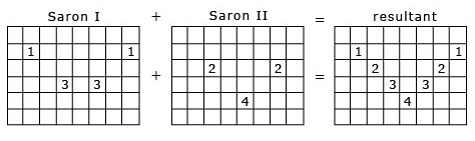

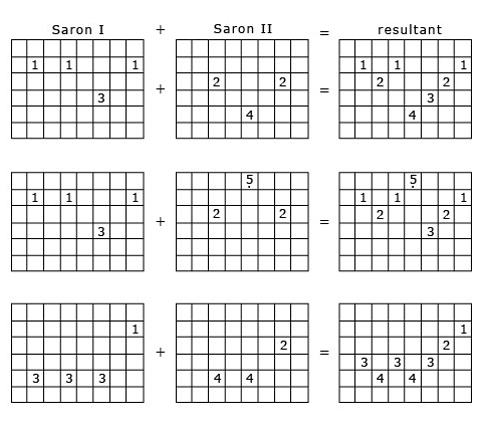

We need next to look at how the gong and jengglong parts fit together. Figure 4 below reproduces the gong player's part laid out above the corresponding beats of the jengglong player's line. The lower part of Figure 4 shows a different way of laying out the same information, incorporating the two parts into the same notation. Notice that the beat divisions have been changed to give 4 sets of 2 beats per line, instead of 8 single beats per line. In effect this is simply a change to give us a neater and less cluttered form of notation. This style of presentation will be helpful as we look at adding yet more instrumental parts to the music.

The next instrument I want to consider adding is the saron. The ensemble uses two, identical, saron, which are played as a pair. The principle of the saron is the same as a xylophone, but it is made of metal (hence the generic term ‘metallophone’). In this particular piece of music, ‘Bendrong’, the two players have a choice of three possible patterns that they can play during the phrase that we have been considering. These alternative lines are called lancaran, canuk and ciaseman. It is important to understand that these three options are alternatives and cannot be played simultaneously; the players select just one of them at the relevant point in the piece.

Activity 8

On the next section of the video, first the lancaran line, then the caruk line and the ciaseman line are demonstrated by the saron players. After a short introduction saron I begins alone; saron II joins in later. The note patterns played by each player are supported by the highlighted notation on the screen to help you to follow what is being played, and how the two parts interlock. Watch the video demonstration of the lancaran, caruk and ciaseman below, trying to follow the notation as you watch. Do not worry if you get lost at first, but replay the video clip until you can follow the notation and hear how the two saron parts interlock

Instrumental part for the saron [5 minutes 49 seconds 15.8MB]

The Activity 5 video is a sequence shot at a wayang golek (rod puppet) performance, filmed for this course in Bandung in 1996. It features the gamelan ‘Galura’, directed by Pa Otong Rasta. This section is from the beginning of the all-night performance, and comprises part of an instrumental prelude. We see most of the instruments and musicians of the gamelan salendro in action. (This sequence pieces together shots of various different instalments taken at different times; the music is not continuous.)

The demonstration video clips in Activities 6 and 7 illustrate some of the simpler parts for the piece ‘Bendrong’. It begins with the gong and kempul parts, then the jengglong part. In the Activity 8 video, three possible versions of the saron parts – named lancaran, caruk and ciaseman – are demonstrated, with notations on screen. (Note: The letter ‘c’ is always pronounced ‘ch’ in Sundanese.)

In Figure 5 I've written out in parallel the parts for gong/kempul, jengglong and the three saron alternatives. You should remember that this is not a score: although I have illustrated parts for several players in parallel there are many other parts not shown here, and moreover the lancaran, caruk and ciaseman parts are alternatives to each other and are not played simultaneously.

Activity 9

Now I'd like you to look at the parts written out in Figure 6 and try to work out the following.

How do the lancaran saron parts relate to the jengglong part?

Bearing in mind your answer to (1), now compare the caruk parts with the lancaran parts. What similarities and differences can you spot between them? (A couple of clues: you will find it useful to begin by looking at a fragment of the line, for instance the first four notes of each saron part. Look, too, at the ends of lines and phrases, i.e. those occurring just before the vertical lines.)

How do the ciaseman parts relate to the other parts illustrated here?

Answer

Here are my answers to those questions.

The lancaran saron I is in fact exactly the same as the jengglong part, with the pitch ‘4’ added before each note: thus ‘5 1’ becomes ‘4541’ and so on. Saron II plays a single repeated pitch (either 1 or 2) before each of the saron I notes. These saron II pitches are the same as the jengglong notes that coincide with gong strokes (to check this, look immediately below each ‘G’).

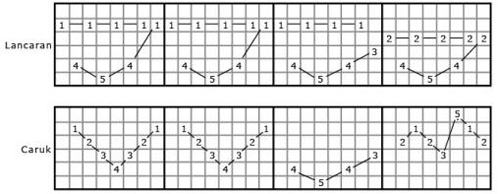

The caruk parts look rather different at first sight, apart from the phrase ‘4543’ which also comes in the lancaran saron I at the same time. Looking at the ends of phrases, however (just before the vertical lines), we see that the notes are identical with both jengglong and lancaran parts. If the similarity is found at the end of each phrase, the difference lies in what happens before this common final pitch. Whereas in lancaran the two saron parts appear to follow a separate logic, in caruk the two only make sense when considered together, because together they form a continuous, conjunct melodic line. Figure 6 indicates how the melody is perceived by the ear: as one continuous line for caruk but as two separate lines for lancaran. Replay the video clips in Activities 6, 7 and 8 if you didn't notice this before.

This is a little harder to identify. Not all the phrase endings are the same, but alternate phrases are. The patterns have something in common with tin-interlocking caruk patterns, but contain more rhythmic and melodic interest, which is clearer if we write the ciaseman part out as in Figure 7.

You should now be getting the hang of some of the basic underlying principles of this music, and of this piece in particular. I'll now elaborate on a few of the principles, starting from a point with which you should already be familiar.

The ends of lines and phrases are particularly important. Thus in this piece we have seen how the first phrase always ends on pitch 1. Examining the rest of the parts we can see that the second phrase ends on a 1, the third on a 3 and so on, giving the pattern shown in Figure 8 below, which records the last note of each phrase. We can call these end-of-phrase notes ‘destination pitches’, while those coinciding with the gong strokes may be termed ‘gong tones’.

If you look back at Figure 5, you can see that the jengglong part simply interpolates the pitch 5 between each of these notes. The lancaran saron I precedes each destination pitch with ‘454…’, while lancaran saron II repeats one of the ‘gong tones’ on the off-beats. In caruk, the two sarons together combine to produce a conjunct melodic line ending on the destination pitch.

Similarly, each of the other instruments has its own idiomatic way (or, like the sarons, choice of ways) of moving to each destination pitch or gong tone. In some cases, the patterns are rather more complex than those we have considered here. Moreover, several instruments can either be played in the kind of simple style illustrated here, or in much more complex and elaborate patterns, depending on the proficiency of the player. The result is that the sound of the group playing together is quite dense and complicated, and yet the underlying structure of the piece is remarkably simple – Sundanese musicians would actually be able to reconstruct all the parts, given only the identity of the two ‘gong tones’.

Although not all Sundanese pieces are this simple in conception, the basic principle that complexity is built on very simple structural foundations certainly does hold true for more complicated pieces. Now we can go on to make some more observations.

3.3 The musicians at work

3.4 Variation

In order to take us this far, I've had to write down a few parts and analyse them. This has clarified some points, but obscured others, the most basic of which can be stated bluntly: virtually every part in every Sundanese gamelan piece is subject to variation. Each player has, as a general rule, not a single correct part but rather a selection of equally correct options. In fact each player knows the basic structure (such as that discussed in Section 3.2), and how to derive the part for his own instrument from that structure. But the rules for deriving a particular part from the basic framework generally allow several possibilities. This applies in cases like that we've covered, where an instrument (saron) has a choice of different types of pattern (lancaran, caruk or ciaseman), but it's also the case that each type of pattern can be realised in several ways. (In this group, like many others in Sunda, the instrumental players are all male, although they are sometimes joined by female singers.)

To give an example, the caruk pattern quoted above is in fact only one of many possibilities. The ‘rule’ is that the two sarons should combine to produce a simple melody ending on a destination pitch. The way this is achieved is by the two sarons effectively dividing up the scale between them. Thus if the destination tone is a 1, saron I will play mostly 1s and 3s; saron II will play 2s, 4s and high 5s. We've looked at one possibility, that saron I plays ‘1331’ and saron II adds ‘.242’, resulting in the conjunct line ‘.1234321’, as laid out in Figure 17.

Following the same principles, Figure 18 shows some other possibilities.

Thus, the lines tend to be mostly conjunct, with only occasional leaps, something which is achieved by the two players carefully listening to each other and responding appropriately. Almost all the parts, as I said, are similarly variable. The result is that, even if the group kept repeating the same basic framework all night, it would never be realised exactly the same way twice.

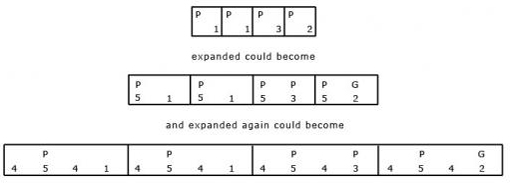

3.5 Expansion and contraction of the piece: wilet

It should already be clear that, in order for this music to work, musicians need to listen out carefully for what their colleagues are doing. For instance, since the saron I has at least three possible patterns to play (lancaran, caruk and ciaseman), the saron II player must keep listening in case his colleague changes from one to another. The same ‘interlocking’ principle applies to certain other instalments too. In order to show just how important group interaction is in this music however, it will be necessary to introduce another factor.

It is common practice in Sundanese gamelan music to change the speed of the gong pattern (and, therefore, of the sequence of destination pitches). Say the piece starts with the gong phrase (i.e. the time which elapses between two strikes of the big gong) lasting X seconds. By decelerating, this phrase can be expanded to 2X, 4X or even 8X seconds. A common pattern is for a piece to go through one, two or more such expansions, and then to return by the same stages to the original level (in some cases a higher or extra-fast level, say with a gong phrase of ½X seconds, may also come into play). These different levels are called wilet. It would be a little misleading to think of this shift as simply a change in tempo. In practice, most players will adjust the number of notes they play per cycle so that the tempo – the speed at which the listener feels the music to be moving – does not change as much as these figures would suggest.

Wilet change has something in common with augmentation and diminution in Western music, but is really a process peculiar to south-east Asian music – I like to think of it as analogous to a machine changing gear. Figure 19 demonstrates this shift, with the gong phrase on the top line keeping the same pattern but spreading it over a longer time, while another instrument continues to play notes at the same speed but has time to play more of them in the same basic gong phrase:

and so on. So although the gong pattern becomes more and more sparse, most of the other parts play at much the same speed, but have time for more notes.

(Note: The melodic notations in Figure 19 are not intended as actual instrumental parts; they have been invented to give a clear picture of the process being described.)

This process has various ramifications, but the most important for us here is that it puts an extra burden on group interaction, since (1) the whole group has to expand and contract the pieces together, while (2) the way the piece will work out (how it will be expanded and contracted, and when) is normally decided only in performance. In practice these changes are signalled aurally by the drummer to the rest of the ensemble and the rhythms he plays enable the group to ‘change gear’ in a co-ordinated fashion.

Activity 10

The next section of video (below) illustrates this wilet change in practice. Watch it now and try to follow what happens: although the whole group is playing, the camera focuses on the drummer and gong player to make this easier. If you concentrate on the gong pattern, which should be quite familiar by now, you will notice the decelerations to successive expansions of the piece. The gong-player is following the drummer's cues – cues which are entirely aural.

Demonstration of wilet changes [3 minutes 31 seconds 9.68MB]

Activity 11

Finally, I'd like you to see and hear how all these things come together. The next video sequence shows two extracts of the whole group playing the piece ‘Bendrong’ together, going through a sequence of expansions and contractions. The music is, I think you'll agree, rather complex – but try to remember as you watch, just how simple the underlying structure is! Watch the video clip below now.

Bendrong played by the whole group [4 minutes 52 seconds 13.1MB]

3.6 Conclusion

I asked the question at the beginning of this section on Sundanese gamelan music: how is it possible for a group of musicians to play highly complex music, in a cohesive manner, without the use of notation and without having to memorise impossibly large amounts of music? My answer came in a number of stages.

Rather than reading, or memorising vast amounts of music, the musicians memorise the simple frameworks of pieces (the Javanese term for this, balungan – literally, skeleton – is sometimes used by Sundanese musicians). Individual parts are all related to these frameworks.

Parts are worked out by the application of simple principles or rules, which allow for several equally valid realisations. Having learned their instrument's part for a few pieces, a musician can apply the same principles to other pieces too, working out the part as he goes along – in performance.

A strong sense of ensemble ensures a cohesive performance. Everyone knows, at least in general terms, how the other instrumental parts go: musicians listen to each other and respond to each other's changes. In particular,

(a) in the case of some instruments (such as the sarons), separate parts interlock to form a coherent whole;

(b) in order to expand and contract the piece together, everyone must listen and respond to aural signals given by the drummer.

To bring this back to the discussion at the beginning of the course, everything I've said about Sundanese gamelan relates quite clearly to Nettl's description of music which is ‘spontaneous but model-bound, rapidly created, and simply conceived’ (see Section 1.2). Somehow neither the term ‘composition’ nor the term ‘improvisation’, as generally understood in the West, quite captures the way this music is created. It should be clear by now, as I have suggested all along, that this dichotomy is a very limited tool for describing musical creation.

4 Some final thoughts

4.1 What is a composition?

We are used, in Western art music, to being able to identify a piece of music and its composer. The ‘piece’ is represented by the written notation; it can be realised in somewhat different ways in different performances. One of the problems we have in applying our concepts of composition to the music of other cultures is that it is not always easy the identify a ‘piece’ of music (an item of repertoire), as distinct from a particular performance.

Activity 12

Bearing this in mind, what problems might you encounter in trying to decide, in the two case studies in this course, how you would define the piece of music being played? How would you try to identify the composers of the pieces in question?

Answer

The performance of Indian music

Here it would be possible to identify something as ‘the piece’ – namely the text and its basic musical setting, which together are termed the bandish or ‘composition’. Insofar as the text determines the music performed, it defines the piece. This may have a known ‘composer’ (although in our example the composer is not known – it is regarded as simply ‘traditional’). However, a great deal of what was performed was determined simply by the chosen rag and tal (melodic and metrical frameworks) which are common to countless other bandishes, with the text playing little or no role. From this perspective, the ‘piece’ was the rag; like most rags, this has no known composer, having been handed down by previous generations of musicians.

The performance of Sundanese gamelan music

The ‘piece’ here could also be interpreted in two different ways. We could identify the piece as the framework (the sequence of destination pitches with which the musicians work), and describe the notes actually played as a realisation in performance. Or we could call the piece the total performance, with all the elaborating parts included. Either way, there is no known composer.

In both cases we have considerable difficulty either defining the ‘piece’ being performed or identifying the ‘composer’ – something quite typical of unwritten music.

4.2 Summary: creating music

Both of these performances clearly belong to traditions where the ‘composer’ and the composer's identified works are rather less important than they are in Western art music. Every performance of Indian or Sundanese music is unique, and yet every performance draws on repertoire and techniques which have been learned. The total repertoire exists not as a set of written works, but in the minds of performing musicians – the music only really exists in performance, and each performance is as valid as the last. It can often be difficult, as we have seen, to distinguish a piece of music from a particular performance. For this reason, many ethnomusicologists prefer to talk about music as a process of re-creation, rather than a collection of musical products.

What the Indian and Sundanese examples have in common, then, is that both are essentially created in performance, with reference to one or more quite detailed models. It would be impossible to predict in advance of a performance exactly which notes would be played in which order, or even how long the performance might take. Despite this, we shouldn't be misled into believing the musicians are free to do what they like. On the contrary, they are constrained by various rules and norms, in the same way as is a Western performer who works from a score (albeit perhaps not to the same degree). Whether or not we choose to call them ‘improvised’ musics is not important. What is important is to find out in each case how the music works, and how the musicians are guided in deciding what to play.

Briefly returning to some of the issues of Section 1, we have seen how different types of music can be described as model-based (examples of models include the rag, and the destination pitches of the gamelan piece); we have seen how they are held together by the stability of certain elements (e.g. the time structure in both cases, i.e. the tal and the gong pattern); and we have seen how the stability and predictability of certain elements allow others to vary.

These are very general observations, and would in some way be applicable to all music (including Western art music). As Nettl points out, however, music which is created in performance is likely to be more model-based, and less innovative, than music worked out in advance (that which is written down, in particular). Composers who give themselves time to think, to sketch, to revise and so on may be tempted to break with tradition, to surprise their audience. Musicians who create music in performance are, in general, more closely tied to the models handed down to them by their tradition.

Whatever differences we may have identified, we should remind ourselves that there are common features between these (largely) unwritten traditions and the Western art music tradition. In particular, there is something in common between these Asian traditions and the work of composers such as Chopin and Berio – between the revision, recomposition and the evolution of written pieces, and the constant regeneration of unwritten music through performance.

Conclusion

This free course provided an introduction to studying the arts and humanities. It took you through a series of exercises designed to develop your approach to study and learning at a distance and helped to improve your confidence as an independent learner.

References

Acknowledgements

This course was written by Professor Martin Clayton

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence

Course image: Nicolas Raymond in Flickr made available under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Licence.

Extracts are taken from AA302 © 2006 The Open University.

Don't miss out:

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University - www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Copyright © 2016 The Open University