Neighbourhood nature

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 24 April 2024, 6:52 PM

Neighbourhood nature

Introduction

In this free course, Neighbourhood nature, you will learn about the plants and animals in an English temperate woodland, how they can provide clues about the history of local woodland and how some traditional woodland management methods can benefit biodiversity. You will also learn about the importance of ancient trees as a habitat for certain rare species of insect and fungus.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of level 1 study in Environment & Development.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

understand how woodland is structured

understand what is meant by the term ‘ancient woodland’ and how such woodland may be recognised

understand how certain woodland management methods can benefit biodiversity

understand the conservation importance of ancient trees.

1 Woodland

It is thought that, following the last glaciation (when most of the UK was covered in ice) and before humans began to have an influence on the vegetation of the UK, the country was covered in natural forests known as wildwood. Very little of this wildwood remains today, it having been cleared for fuel and to create space for agriculture. However, those woods that do remain are there because humans, through the ages, have managed and maintained them to exploit the woodland for timber, fuel and food. Every wood has a history of interaction between humans and nature that can be revealed by careful observation. Oak woodland is the most species-rich habitat in the UK, so woods are good places to see wildlife – even in well used woods within and near cities.

Activity 1

Watch the following video clip and then answer the following question.

Transcript: Sherwood Forest

Sherwood Forest

A microhabit is a small habitat within an ecosystem, which supports the survival of certain animals or plants. How many different microhabitats did you notice in the clip?

Answer

The trees provide nesting, roosting and feeding places for birds. Open areas (glades and clearings) without trees are important for certain plants, butterflies and other insects. Dead wood provides habitat for invertebrates and fungi. Dead vegetation on the woodland floor is important for fungi and invertebrates.

So woodland is a diverse habitat, rich in wildlife, that needs to be managed to maintain that richness.

1.1 Woodland structure

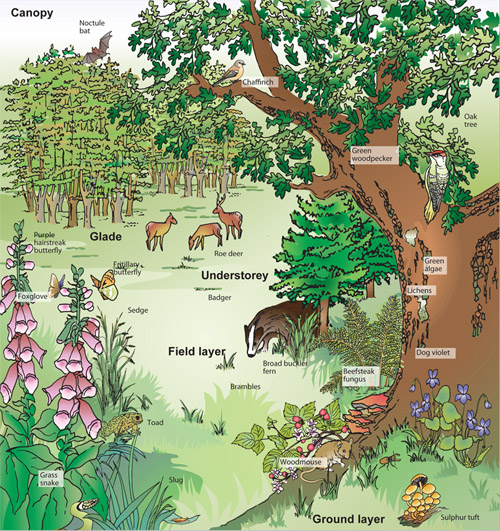

Most woods have a number of vegetation layers (Figure 1). There is the canopy, or top layer, where the tallest trees are found, such as oak (Quercus robur), ash (Fraxinus excelsior), beech (Fagus sylvatica) or birch (Betula pendula). These trees receive the maximum amount of light available.

The understorey is composed of shorter trees or shrubs, such as field maple (Acer campestre), hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna) or hazel (Corylus avellana), which are adapted to grow successfully with less light, as well as saplings of canopy tree species.

The herb or field layer may include ferns such as the broad buckler fern (Dryopteris dilatata), flowering plants such as the wood anemone (Anemone nemorosa) and grasses.

The ground layer is composed of mosses, lichens, ivy (Hedera helix) and fungi. On the woodland floor there is usually a layer of rotting leaves and vegetation, which is home to a range of invertebrates such as springtails (Collembola), woodlice (Oniscidea) and millipedes (Diplopoda).

Climbing plants, such as honeysuckle (Lonicera periclymenum), grow up tree trunks to reach towards the light. Others, such as certain mosses, lichens and ferns, grow attached to tree trunks in order to reach light – they are epiphytes, plants that grow on other plants only for support and do not obtain nutrients from them.

Question 1

If light is so important for plant growth, how do you think species such as bluebells manage to survive growing under dense shade?

Answer

Species such as bluebells survive under the shade of the canopy because they normally complete their life cycle in early spring, before the leaves fully open in the tree canopy above. Other species are simply tolerant of shade or grow in the parts of the woodland that receive more light, such as gaps between trees, glades or at the woodland edge. Coppicing encourages such species.

1.2 Woodland species

Some woodland plants and animals are generalist species. They are found in woodland, but are also common in other habitats such as grassland, scrub, parks and gardens. Examples might include plants such as ivy or germander speedwell (Veronica chamaedrys), animals such as foxes or hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus), or birds like bluetits and chaffinches (Fringilla coelebs).

Others might use the wood as a convenient place for just part of the time. For instance, Leisler's bat (Nyctalus leisleri) hibernates in woodland trees in winter and the chiffchaff (Phylloscopus collybita) migrates to woodland for the summer.

At the opposite end of the spectrum are the true woodland specialist species. These species rely on trees and woods throughout their life cycle: birds such as the nuthatch (Sitta europaea) and all three species of woodpecker; mammals such as the red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris); and specialist lichens and mosses such as the striated feather moss (Eurhynchium striatum).

You will recall from the clip that species found in woodland differ widely in their requirements, from the silver washed fritillary butterfly (Figure 2) that likes sunny patches in woodland glades to the black snake millipede (Tachypodoiulus sp.) that thrives on rotting wood and the birch polypore fungus that is found only on birch (Betula sp.).

The abundance of a particular species may also depend on how specialist it is. Once a common sight, the white letter hairstreak butterfly (Satyrium w-album) has declined dramatically with the loss of its only food plant – the elm (Ulmus sp.) – to Dutch elm disease.

The species perhaps most associated with woodland are squirrels. The native red squirrel is now only found in scattered populations in northern and western areas of the UK and on the Isle of Wight. It has suffered from loss of habitat, the deadly squirrel poxvirus and competition from the grey squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis), which was introduced from North America in the nineteenth century.

All of the UK's seventeen species of bat can be found in or around woodlands, but some are woodland specialists – such as the noctule (Nyctalus noctula), barbastelle (Barbastella barbastellus), Bechstein's (Myotis bechsteinii) and brown long-eared bat (Plecotus auritus). Brown long-eared bats prefer to forage in deciduous woodland (composed mainly of trees that lose their leaves in winter), where they glean insects from leaves and bark. Noctule bats are primarily tree dwellers and live mainly in rot holes and old woodpecker holes. Barbastelle bats roost in trees all year round, preferring ancient woodland with a substantial understorey.

Leaf litter is eaten and broken up by detritivores. These are invertebrates such as millipedes and woodlice. The decomposers (species of fungi and bacteria) continue the process and undertake chemical breakdown of the litter. Saproxylic species are those that obtain their nourishment solely from dead or decaying wood. By their actions, these groups of organisms release nutrients and make them available to be taken up by other plants.

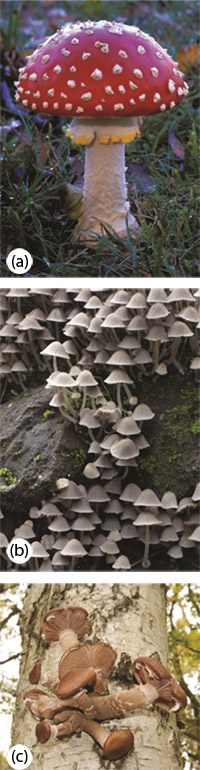

Most fungi associated with woodland conform to one of the following alternative nutritional strategies:

- They are in a mutually beneficial (symbiotic) feeding relationship with tree roots, e.g. fly agaric fungus (Amanita muscaria) is associated with birch trees.

- They decompose wood or leaf litter, e.g. fairy bonnet (Coprinus disseminatus).

- More rarely, they may adopt a parasitic relationship, causing damage to the trees, e.g. honey fungus (Armillaria mellea).

It is the fruiting body of a fungus (the stage that produces the spores) that appears above ground, normally in warm and damp conditions (Figure 3).

1.3 Woodland history

'Ancient woodland' is a term mentioned in the next video clip – 'Archer's Wood'. This section aims to give a quick woodland history and show how ancient woodland fits in.

Activity 2

Watch the video below.

Transcript: Archer's Wood

S159 Neighbourhood Nature DVD Transcript: Archer's Wood: aging woodland

After the last glaciation, woodland grew to cover much of the UK. This naturally established wood was known as wildwood, but since Neolithic times (between 6000 and 4000 years ago) it has been progressively influenced by the activities of humans – either through management or complete clearance for farming. By the time the Domesday Book was produced (1086), around only 15 per cent of England was wooded.

Foresters tend to classify woodland based on its age, history and the types of trees found growing within it.

Primary woodland has existed continuously since the end of the last glaciation. Any surviving today is inevitably a tiny fragment of the original area.

Secondary woodland originated in areas that have at some time been unwooded, e.g. land used at some point in history for agriculture but was later allowed to revert to woodland. Virtually all land in the UK could eventually become woodland if left without interference from factors such as grazing, mowing or ploughing. You can probably think of examples of wasteland or uncultivated fields in your area where this process is starting to happen.

Plantations are areas of woodland where the trees have been deliberately planted. Non-native conifers – trees with needles that bear cones and are often evergreen, retaining a covering of leaves all year round, e.g. Norway spruce (Christmas tree) (Picea abies) – were popular choices during the twentieth century. Plantation woodlands were established primarily for timber production, often by the Forestry Commission, but may now have an important recreational role.

In the UK the term ancient woodland is used to mean land that has been continuously wooded since at least 1600. In practice, ancient woodland could be primary, secondary or even plantation, as long as it has been continuously wooded.

1.4 Ancient woodland

The classic image of ancient woodland is probably an oak wood in southern England, with swathes of bluebells and other flowers, as seen in Archer's Wood. However, ancient woods across the UK come in many shapes and forms, from the remnants of Scottish native pinewoods, home of the capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus), to the oak and hazelwoods of the western Atlantic seaboard, characterised by lush growth of ferns, mosses and lichens.

The ancient woodland habitat has had centuries to develop and generally hosts a greater number of species than more recent woods – especially rare or localised species. It is considered an irreplaceable habitat – the UK's equivalent of the rainforest – by conservationists.

Determining whether a wood is ancient is like piecing together a jigsaw puzzle. Old maps and documents may provide strong evidence, as can the wood's name, but there are also clues in the wood itself. Historical features (e.g. medieval wood banks, old coppice stools and remnant field boundaries) tell of past land use, and the species that are found in the wood may also indicate antiquity.

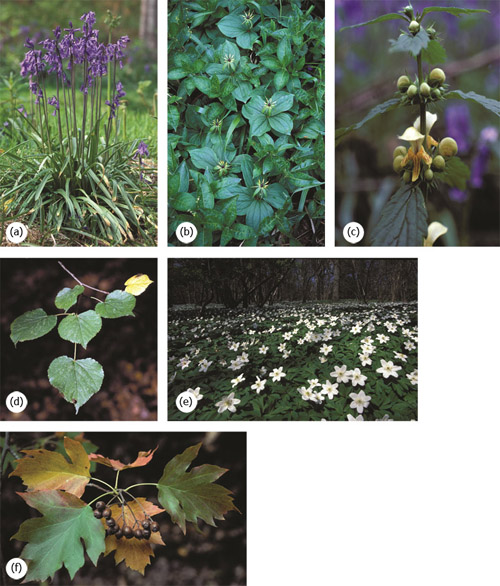

The presence of certain indicator species is evidence of ancient woodland. Generally, 'ancient woodland indicators' are species that do not colonise new areas easily. Recall the presence of saproxylic beetles in Sherwood Forest, which are good indicators because of their poor powers of dispersal. However, flowering plants are most often used because they are easy to identify. They should be used with caution, though, as one plant may behave differently in different parts of the country (for example, in the north of England bluebells are not always restricted to woodland). Generally, it is not enough to find one 'indicator'; a number of plants from a list appropriate for that region is needed, and this should be used in conjunction with other evidence.

In the south of the UK, plants such as the bluebell (the native species Hyacinthoides non-scripta), wood anemone, herb paris (Paris quadrifolia) and yellow archangel (Lamiastrum galeobdolon) can act as ancient woodland indicators (Figure 4).

Question 2

In the 'Archer's Wood' clip, which species are identified as indicators of ancient woodland?

Answer

Wild service tree (Sorbus torminalis), bluebells and pendular sedge (Carex pendula).

In northern parts of the UK, though, mosses, liverworts and lichens may be better, since many of the southern indicators appear to live equally happily in open habitats in the north.

Trees that may indicate ancient woodland include the wild service and the smallleaved lime (Tilia cordata), which reproduce mainly by suckering (producing new shoots directly from the tree's root system) because the current climate is too cold for reliable seed production.

Today, ancient woods cover only around 2 per cent of the UK and are often small, isolated fragments. Online maps are available to help you to find out if any of your local woods are ancient.

Ancient woodland is under threat as most ancient woods are not in legally protected areas such as historic parks, landscapes and Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Although planning policy is more sympathetic now than in the past, policy makers still allow clearance for developments such as new roads or airports. Ancient woodland may also suffer indirect damage such as pollution from intensive farming.

During the twentieth century, 29 per cent of the ancient woodland in the UK was cleared and replanted with conifers. Remnants of the unique communities of animals and plants remain, but conservationists are concerned they will be lost if these woods are not restored by gradual removal of the conifers, allowing native species to regrow.

1.5 Woodland management

Woodland in the UK has been managed for centuries.

The use of coppicing is where a tree or shrub is cut back to the base at ground level, allowing new shoots to develop. These coppice stools (Figure 5) were used to provide a regular supply of twigs and branches for fuel (e.g. charcoal), fodder, or for making fencing hurdles or baskets.

Trees were also selected and felled for their timber, e.g. to provide planks for building.

Pollarding is similar to coppicing, but the tree is cut at eight to twelve feet from the ground. This practice was often used in wood pasture (open areas where grazing animals co-exist with trees). Cutting at this greater height protected the new shoots from browsing.

Permanent open spaces in woodlands are created as rides and glades. A ride is a wide route through the wood, often unsurfaced, that is managed as a tree-free area and is useful for access and timber extraction. A glade is a woodland clearing kept free of trees by grazing or mowing. Temporary open areas are also created by coppicing patches of the wood in rotation.

Active management has been a key factor in developing the character of the UK's woods. Allowing the penetration of light through coppicing, glades and rides encourages high numbers of the more charismatic woodland wildlife, ranging from spring flowers to butterflies. However, there is debate among conservationists as to whether this type of management is appropriate for all woods and all species. There are many species that prefer shadier, cooler and moister conditions, but these tend to be overlooked species such as beetles, mosses and fungi.

Question 3

Coppicing is one way of managing woodlands. What is the effect of coppicing?

Answer

It creates a variety of habitats within the wood. It lets light onto the woodland floor, encouraging ground flora such as bluebells and yellow archangel (Lamiastrum galeobdolon), and butterflies such as the silver washed fritillary.

1.6 Summary

- Woodlands have a number of vegetation layers. The tops of the tallest trees are in the canopy; the understorey consists of shorter trees and shrubs; beneath this is the field layer, which consists of flowering plants and ferns; the ground layer consists of mosses and fungi, and a layer of rotting leaves and dead wood.

- Ancient woodland is land that has been continuously wooded since at least 1600. Evidence that a wood is ancient can be determined by looking at old maps and by searching for the presence of indicator species and historic features, such as old coppice stools and remnant field boundaries.

- Active management of woodland using methods such as coppicing increases its variety of habitats, which is important for certain species such as the silver washed fritillary.

2 Ancient trees

The 'Sherwood Forest' clip in Activity 1 mentioned that one piece of evidence for an ancient wood was the presence of ancient trees. However, ancient trees are a habitat of conservation importance in their own right. Not only are they are a valued part of the UK's heritage and culture, they also support wildlife that cannot live anywhere else. Ancient trees are home to hundreds of specialised species, many of which are extremely rare. The UK has more ancient trees than anywhere else in Europe, so those that are here are of international importance.

Today, many of the surviving ancient trees can be found in the vestiges of the once extensive system of royal hunting forests and their successors, the more formalised medieval deer parks. Scattered groups of trees can also be found in historic parkland, wood pasture and ancient wooded commons. Small groups and individual specimens can also be found in the midst of housing estates and urban parks, on farmland, village greens, churchyards, and within the grounds of historic buildings. In the open countryside, scattered across much of England, ancient black poplars (Populus nigra) can be found on flood plains in meadows and occasionally in ancient hedges.

2.1 Characteristics of ancient trees

Trees have three stages in their lives – formative, full to late maturity (or veteran), and ancient. The length of these stages can vary depending on the species, the environment in which the tree has lived and what happens to it during its lifetime.

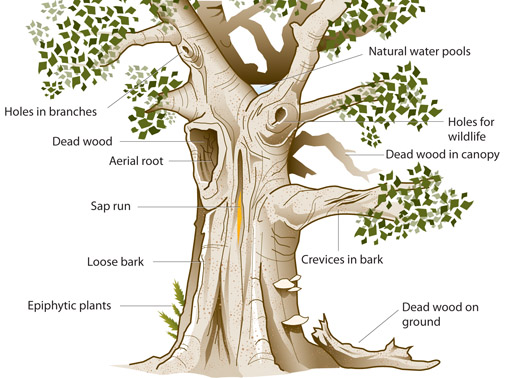

An ancient tree is one which is in the final stage of its life. It is old compared with others of the same species, and often has a wider trunk. (Recall from the clip 'Sherwood Forest' how the age of the tree was estimated by measuring the girth of the trunk.) Table 1 defines the minimum tree girth to distinguish ancient trees for different species. The canopy of an ancient tree is retrenching or 'growing downwards', giving the tree its distinctive squat, fat appearance, often with protruding deadwood and a hollowed trunk (Figure 6).

| Trunk girth (minimum) | Tree species |

| 190 cm | Birch species, hawthorn |

| 240 cm | Field maple, rowan, grey and goat willow, hornbeam, holly, cherry, alder |

| 310 cm | Oak species, ash, Scot's pine, yew, elm species |

| 470 cm | Lime species, sycamore, horse chestnut, poplar species, other pine species, beech, sweet chestnut, white and crack willows |

2.2 The importance of ancient trees for specialist insects and fungi

Figure 6, as seen in the previous section, shows the range of features on the outside of ancient trees (such as deadwood on the ground, water pools, sap runs and holes) that provide habitats for the specialist species of lichen, fungi and insects. However, it is the process of hollowing by fungi that makes an ancient tree a habitat in its own right: the relatively stable temperature and humidity inside the tree provide the optimum environment for the growth of fungi and insect larvae. The sulphur polypore (Laetiporus sulphureus), a specialised wood decay fungus, softens the wood in the centre of the tree (Figure 7). As the wood decays, it becomes an attractive habitat for many rare invertebrates such as the hairy fungus beetle (Mycetophagus piceus) or the click beetles (Lacon querceus), the cardinal click beetle (Ampedus cardinalis) or the rusty click beetle (Elater ferrugineus). Some of these insects are so rare that they are known to exist at only one or two sites in the UK, such as some of the London parks and Windsor Great Park. The western wood-vase hoverfly (Myolepta potens) was thought to be extinct in the UK, since it had not been recorded for forty years – but larvae of this species were recently found in a pool of water in an ancient tree.

The various creatures and the fungi work together to recycle the dead wood, ensuring that the vital minerals and nutrients are pushed back down into the soil as a part of the rotting process, providing essential food for the trees' continued longevity.

The fungi and invertebrates found in ancient trees are so well adapted to the benign conditions within the trees that they cannot exist anywhere else. It can take 200 years for a tree to develop the conditions suitable for these organisms. Even trees as old as 100 years are unlikely to be suitable. Many of the specialist species dependent on ancient trees have poor powers of dispersal: if the tree they inhabit is destroyed it is unlikely that there will be another suitable tree nearby, so the effects of the loss of an ancient tree are irreversible.

Even in this ancient stage of its life, a tree may live for decades – even centuries. The older the tree, the more valuable it becomes as a habitat. The Major Oak in Sherwood Forest, which features in the clip, is perhaps the best known ancient tree in the UK. You can probably think of some examples of ancient trees near you.

Veteran trees are ancient trees of the near future. They have reached the mature phase of their lives and show signs of hollowing and decay. They often display a smaller selection of the same important wildlife and habitat features.

The UK is believed to have around 100,000 ancient and veteran trees – more than any other country in Europe. These trees are currently in the process of being recorded onto the Ancient Tree Hunt national inventory by volunteers. Unlike historic buildings, ancient or heritage trees have no specific legal safeguard. Without protection, ancient trees are often felled before any planning application is made. Trees with historic or biodiversity value can, however, be protected through Tree Preservation Orders (TPOs), or they may be situated within protected areas such as Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI).

Question 4

Trees are large organisms that cast shade under their branches and provide microhabitats for other organisms. What other types of organism have been mentioned in this course?

Answer

Butterflies such as the silver washed fritillary (Argynnis paphia), saproxylic beetles, millipedes and fungi such as birch polypore fungus (Piptoporus betulinus).

2.3 Summary

- Ancient trees are a habitat of conservation importance in their own right, supporting many rare and threatened species of fungi and saproxylic insects.

- Ancient trees provide a range of microhabitats such as rot holes, water pools and dead heartwood.

- The UK has more ancient trees than any other country in Europe.

- Due to the isolated nature of ancient trees and the poor dispersal powers of the specialist fungi and insects dependent on them, the effects of the loss of each tree on these species is irreversible.

Conclusion

This free course provided an introduction to studying Environment & Development. It took you through a series of exercises designed to develop your approach to study and learning at a distance, and helped to improve your confidence as an independent learner.

Acknowledgements

Course image: Chris Moody in Flickr made available under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons licence). See Terms and Conditions.

This course was written by Donal O'Donnell.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Kate Lewthwaite (Woodland Trust)

Neighbourhood Nature was produced as part of the OPAL (Open Air Laboratories) Project, which is funded by the Big Lottery Fund.

© iStockphoto

© BBC

Figures 2, 3(a-c), 4(a-f), 6: © Mike Dodd

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out:

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University - www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Copyright © 2016 The Open University