Groups and teamwork

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 19 April 2024, 1:59 AM

Groups and teamwork

Introduction

Are you always the quiet one when it comes to group discussion? This course will help you improve your working relationships with other people in groups of three or more. This course also deals with project life cycles, project management and the role of the leader.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of level 1 study in Engineering

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

describe the main features of work groups and teams

discuss the main group processes that affect work group or team effectiveness

describe the main features of projects, project teams and project management

discuss some types of theories about effective leadership.

1 course outline

The focus of this course is on relating to groups of other people rather than one-to-one relationships. Reading 1 develops some general concepts about 'groups' and 'teams', not just those at work. The later readings look at groups from particular perspectives or contexts, with the aim of discovering ideas about how to make them function more effectively.

This is, in fact, the main aim of this course: to help you understand how you might function more effectively in a group by improving your working relationships. There are difficulties in tackling this aim via a set of readings like this. More traditional ways of tackling it involve training programmes that emphasise the importance of experiencing the issues involved. There is no doubt that, without the experiencing, the ideas remain theoretical and will not actually help you to improve the way that you function, just as reading a cookery book cannot alleviate hunger. To have any effect, the ideas (or the recipes) have to be put into practice.

Putting the ideas into practice involves thinking about yourself and others in a different way. This runs straight into the obstacle of the deeply ingrained habits that we all have in thinking in this area. I suggest that you adopt a quite moderate aim at first and try out one or, at most, two of the ideas presented. Choose the idea that seems to you most attractive, for whatever reason, and decide upon some specific occasions when you are going to put it into effect. Whenever possible, try to enlist the help of someone else to give you feedback on how you performed. The pay-off you get from this limited experiment will probably encourage you to try another idea. That's fine, but don't get carried away and try everything at once; you'll simply forget and frustrate yourself. If you can add one or two new approaches or insights to your repertoire of relating to others, then this course will have achieved its major objective.

Reading 2 is concerned with the dynamics of group behaviour. This is a very broad topic and the subject of many textbooks. The initial approach taken in the reading is to look at the basis on which people are members of a group. The main part of the discussion of groups is concerned with the way that groups evolve and the sorts of process that determine whether the group is successful or not. This provides a number of ideas that can be used to make sense of group behaviour and to help a group function more effectively.

Another side of working in groups is how to cope in, or with, a team of people who have been set up to work on a specific project. Reading 3 looks at the nature of projects and the consequent effects on the team or teams of people involved. Projects also tend to have project managers, raising issues about leading other people rather than just working alongside them.

This final aspect of leadership is also the subject of Reading 4. Again, this is another vast area of interest where there are dozens of theories and prescriptions about how to be an effective leader. Some indication of the range of these theories is given in the reading, and their strengths and weaknesses are assessed. It becomes clear that there is no simple prescription for being a good leader; yet there are some characteristics that most effective leaders have in common.

2 Reading 1 Groups and teams

2.1 What is a group?

Our tendency to form groups is a pervasive aspect of organisational life. As well as formal groups, committees and teams, there are informal groups, cliques and cabals.

Formal groups are used to organise and distribute work, pool information, devise plans, coordinate activities, increase commitment, negotiate, resolve conflicts and conduct inquests. Group working allows the pooling of people's individual skills and knowledge, and helps compensate for individual deficiencies. It has been estimated that most managers spend 50 per cent of their working day in one sort of group or another, and for top management of large organisations this can rise to 80 per cent. Thus formal groups are clearly an integral part of the functioning of an organisation.

No less important are informal groups. These are usually structured more around the social needs of people than around the performance of tasks. Informal groups usually serve to satisfy needs of affiliation, and act as a forum for exploring self-concept as a means of gaining support, and so on. However, these informal groups may also have an important effect on formal work tasks, for example by exerting subtle pressures on group members to conform to a particular work rate, or as 'places' where news, gossip, etc., is exchanged.

2.2 What is a team?

Activity 1

Write your own definition of a 'team' (in 20 words or less).

You probably described a team as a group of some kind. However, a team is more than just a group. As noted above, when you think of all the groups that you belong to, you will probably find that very few of them are really teams. Some of them will be family or friendship groups that are formed to meet a wide range of needs such as affection, security, support, esteem, belonging or identity. Some may be committees whose members represent different interest groups and who meet to discuss their differing perspectives on issues of interest.

In this reading the term 'work group' (or 'group') is often used interchangeably with the word 'team', although a team may be thought of as a particularly cohesive and purposeful type of work group. We can distinguish work groups or teams from more casual groupings of people by using the following set of criteria (based on those proposed by Adair, 1983). A collection of people can be defined as a work group or team if it shows most, if not all, of the following characteristics:

a definable membership: a collection of three or more people identifiable by name or type;

a group consciousness or identity: the members think of themselves as a group;

a sense of shared purpose: the members share some common task or goals or interests;

interdependence: the members need the help of one another to accomplish the purpose for which they joined the group;

interaction: the members communicate with one another, influence one another, react to one another;

sustainability: the team members periodically review the team's effectiveness;

an ability to act together, as one.

Usually, the tasks and goals set by teams cannot be achieved by individuals working alone because of constraints on time and resources, and because few individuals possess all the relevant competences and expertise. Sports teams or orchestras clearly fit these criteria.

Activity 2

List some examples of teams of which you are a member – both inside and outside work – in your learning file. Now list some groups. What strikes you as the main differences?

Your team examples probably highlight specific jobs or projects in your workplace, or personal interests and hobbies outside work. Teamwork is usually connected with project work and this is a feature of much work, paid and unpaid. Teamworking is particularly useful when you have to address risky, uncertain or unfamiliar problems where there is a lot of choice and discretion surrounding the decision to be made. In the area of voluntary and unpaid work, where pay is not an incentive, teamworking can help to motivate support and commitment because it can offer the opportunities to interact socially and learn from others. Furthermore, people usually support what they create (Stanton, 1992).

By contrast, many groups are much less explicitly focused on an external task. In some instances, the growth and development of the group itself is its primary purpose; process is more important than outcome. Many groups are reasonably fluid and less formally structured than teams. In the case of work groups, an agreed and defined outcome is often regarded as a sufficient basis for effective cooperation and the development of adequate relationships.

Clearly there are overlaps between teams and groups: they are not wholly distinct entities. Both can be pertinent in personal development as well as organisational development and managing change. In such circumstances, when is it appropriate to embark on teambuilding rather than relying on ordinary group or solo working?

In general, the greater the task uncertainty the more important teamworking is, especially if it is necessary to represent the differing perspectives of concerned parties. This is evident in government decision making, in areas such as technology and innovation policies, where scientific facts may be collated to support opposing arguments for new policy developments. In such situations, the facts themselves do not always point to an obvious policy or strategy for innovation, support and development: decisions are partially based on the opinions and the personal visions of those involved. When expertise does not point to obvious solutions for problems, teamworking can often come up with a compromise between the varying perspectives and vested interests of concerned parties.

There are risks and dangers, however. Under some conditions, teams may produce more conventional, rather than more innovative, responses to problems. The reason for this is that team decisions may regress towards the average, with group pressures to conform cancelling out more innovative decision options (Makin, Cooper and Cox, 1989). It depends on how innovative the team is, in terms of its membership, its norms and its values.

Teamwork may also be inappropriate when you want a fast decision. Team decision making is usually slower than individual decision making because of the need for communication and consensus about the decision taken. Despite the business successes of Japanese companies, it is now recognised that promoting a collective organisational identity and responsibility for decisions can sometimes slow down operations significantly, in ways that are not always compensated for by better decision making.

2.3 Types of teams

Different organisations or organisational settings lead to different types of team. The type of team affects how that team is managed, what the communication needs of the team are and, where appropriate, what aspects of the project the project manager needs to emphasise. A work group or team may be permanent, forming part of the organisation's structure, such as a top management team, or temporary, such as a task force assembled to see through a particular project. Members may work as a group continuously or meet only intermittently. The more direct contact and communication team members have with each other, the more likely they are to function well as a team. When a group as a whole functions well, then not only do the individual members of the group function well, but they also tend to gain a sense of satisfaction from being part of the group. Thus getting a group to function well is a much prized management aim.

Below, I discuss some common types of team. Many teams may not fall clearly into one type, but may combine elements of different types.

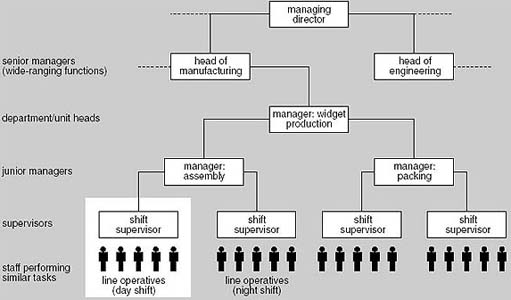

Many organisations have traditionally been managed through a hierarchical structure. This general structure is illustrated in Figure 1, and consists of:

staff performing similar tasks – grouped together reporting to a single supervisor;

junior managers – responsible for a number of supervisors and their groups;

groups of junior managers – reporting to departmental heads;

departmental heads – reporting to senior managers, who are responsible for wide-ranging functions such as manufacturing, finance, human resources and marketing;

senior managers – reporting to the managing director, who may then report to the Board.

The number of levels clearly depends upon the size and to some extent on the type of the organisation. Typically, the 'span of control' (the number of people each manager or supervisor is directly responsible for) averages about five people, but this can vary widely.

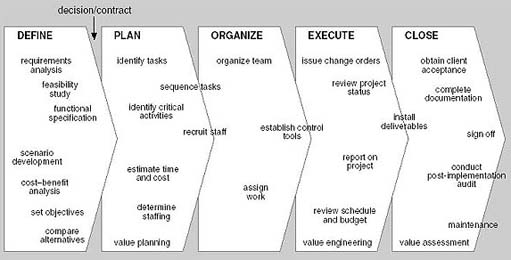

While the hierarchy is designed to provide a stable 'backbone' to the organisation, projects are primarily concerned with change, and so tend to be organised quite differently. Their structure needs to be more fluid than that of conventional management structures. There are four commonly accepted types of project team: the functional team, the project (single) team, the matrix team and the contract team.

2.3.1 The functional team

The hierarchical structure described above divides groups of people along largely functional lines: people working together carry out the same or similar functions. A functional team is a team in which work is carried out within such a functionally organised group. This can be project work. In organisations in which the functional divisions are relatively rigid, project work can be handed from one functional team to another in order to complete the work. For example, work on a new product can pass from marketing, which has the idea, to research and development, which sees whether it is technically feasible, thence to design and finally manufacturing. This is sometimes known as 'baton passing' – or, less flatteringly, as 'throwing it over the wall'!

2.3.2 The project (single) team

The project, or single, team consists of a group of people who come together as a distinct organisational unit in order to work on a project or projects. The team is often led by a project manager, though self-managing and self-organising arrangements are also found. Quite often, a team that has been successful on one project will stay together to work on subsequent projects. This is particularly common where an organisation engages repeatedly in projects of a broadly similar nature – for example developing software, or in construction. Perhaps the most important issue in this instance is to develop the collective capability of the team, since this is the currency for continued success. People issues are often crucial in achieving this.

The closeness of the dedicated project team normally reduces communication problems within the team. However, care should be taken to ensure that communications with other stakeholders (senior management, line managers and other members of staff in the departments affected, and so on) are not neglected, as it is easy for 'us and them' distinctions to develop.

2.3.3 The matrix team

In a matrix team, staff report to different managers for different aspects of their work. Matrix structures are often, but not exclusively, found in projects. Staff will be responsible to the project manager for their work on the project while their functional line manager will be responsible for other aspects of their work such as appraisal, training and career development, and 'routine' tasks. This matrix project structure is represented in Figure 2.

In this form of organisation, staff from various functional areas (such as design, software development, manufacturing or marketing) are loaned or seconded to work on a particular project. Such staff may work full or part time on the project. The project manager thus has a recognisable team and is responsible for controlling and monitoring its work on the project.

However, many of the project staff will still have other duties to perform in their normal functional departments. The functional line managers they report to will retain responsibility for this work and for the professional standards of their work on the project, as well as for their training and career development. It is important to overcome the problems staff might have with the dual reporting lines (the 'two-boss' problem). This requires building good interpersonal relationships with the team members and regular, effective communication.

2.3.4 The contract team

The contract team is brought in from outside in order to do the project work. Here, the responsibility to deliver the project rests very firmly with the project manager. The client will find such a team harder to control directly. On the other hand, it is the client who will judge the success of the project, so the project manager has to keep an eye constantly on the physical outcomes of the project. A variant of this is the so-called 'outsourced supply team', which simply means that the team is physically situated remotely from the project manager, who then encounters the additional problem of 'managing at a distance'.

2.3.5 Mixed structures

Teams often have mixed structures:

some members may be employed to work full time on the project and be fully responsible to the project manager. Project managers themselves are usually employed full time.

others may work part time, and be responsible to the project manager only during their time on the project. For example, internal staff may well work on several projects at the same time. Alternatively, an external consultant working on a given project may also be involved in a wider portfolio of activities.

some may be part of a matrix arrangement, whereby their work on the project is overseen by the project manager and they report to their line manager for other matters. Project administrators often function in this way, serving the project for its duration, but having a career path within a wider administrative service.

yet others may be part of a functional hierarchy, undertaking work on the project under their line manager's supervision by negotiation with their project manager. For instance, someone who works in an organisation's legal department may provide the project team with access to legal advice when needed.

In relatively small projects the last two arrangements are a very common way of accessing specialist services that will only be needed from time to time.

2.3.6 'Horses for courses'

Different team structures have different advantages and disadvantages. A structure may fit a particular task in one organisation better than another. On the next page, Table 1 sets out the strengths and weaknesses of different team structures.

| Strengths | Weaknesses | |

|---|---|---|

| Functional | Lowest administration costs Reasonably successful in past | Coordination across functional areas is more difficult |

| Reasonably successful in past | Inflexible | |

| Pools technical and professional expertise | Communication across functional areas is more difficult | |

| Handles routine work well | Long, slow chain of command | |

| Allows training and apprenticeship in departments | Possibly poor communication with client | |

| Line management has control of projects and change | Tends to push decision making upwards | |

| Easy to set up and terminate projects | Novel objectives difficult to achieve | |

| Limits career development outside recognised paths for staff members | ||

| Tends to dampen creative initiatives | ||

| Matrix | Acceptable to 'traditional' managers | Dual reporting lines of project staff |

| Retains functional strengths and control of paperwork | Staff appraisal and performance measurement difficult | |

| Some planning power in project team | Can cause conflicts of priorities for staff | |

| Faster start-ups | Wider skills required of project manager (e.g. teambuilding more difficult) | |

| Top management retains control of projects but relieved of day-to-day decisions | Project manager may not be able to influence who is assigned to the project | |

| Flexibility of personnel assigned | Dilutes the resources available from functional areas | |

| Reasonable interface with clients and customers is possible | ||

| Some teambuilding is possible | ||

| Project | Greater authority and control | High administrative costs |

| Team members contribute to, and share, objectives | Project manager involved in more administration | |

| Teambuilding and communication made easier | Difficult to graft on to established organisations | |

| Quicker decisions | Project more difficult to terminate | |

| Fewer political problems Good client contacts | Project staff may feel a lack of job security | |

| Good client contacts | Project staff may feel let down on return to functional job | |

| High degree of management skills development | Project staff may feel they have undefined career paths | |

| Easier for top management to coordinate and influence | Slow to mobilise | |

| Can give career development/change for team members | Often limited number of good project staff available | |

| Builds synergy in team | ||

| Clear responsibilities, can be profit centres |

2.3.7 New types of team

In addition to the traditional types of teams or groups outlined above, recent years have seen the growth of interest in two other important types of team: 'self-managed teams' and 'self-organising teams'.

During the 1990s many organisations in the UK became interested in notions of empowerment and, often as a consequence, set up self-managed or empowered teams. An Industrial Society Survey (1995) commented:

the trend is becoming a powerful one, set to take self managed teams from leading edge status to mainstream.

A typical self-managed team may be permanent or only temporary. It operates in an informal and non-hierarchical manner, and has considerable responsibility for the way it carries out its tasks. It is often found in organisations that are developing total quality management and quality assurance approaches. The Industrial Society Survey observed that:

Better customer service, more motivated staff, and better quality of output are the three top motives for moving to [self-managed teams], managers report.

In contrast, organisations that deliberately encourage the formation of self-organising teams are comparatively rare. Teams of this type can be found in highly flexible, innovative organisations that thrive on creativity and informality. These are modern, often very new, organisations that recognise the importance of learning and adaptability in ensuring their success and continued survival. However, self-organising teams exist, unrecognised, in many organisations. For instance, in traditional, bureaucratic organisations, people who need to circumvent the red tape may get together in order to make something happen and, in so doing, spontaneously create a self-organising team. The team will work together, operating outside the formal structures, until its task is done and then it will disband.

Table 2 shows some typical features of self-managed and self-organising teams.

| Self-managed team | Self-organising team |

|---|---|

| Usually part of the formal reporting structure | Usually outside the formal reporting structure |

| Members usually selected by management | Members usually self-selected volunteers |

| Informal style of working | Informal style of working |

| Indirectly controlled by senior management | Senior management influences only the team's boundaries |

| Usually a permanent leader, but may change | Leadership variable – perhaps one, perhaps changing, perhaps shared |

| Empowered by senior management | Empowered by the team members and a supportive culture and environment |

With both forms of team, managers need to rethink their traditional approach to teamworking. Equality of team membership is a key feature of modern teams, with every member playing an equally important role in discussions, problem solving and decision making processes.

Managers are no longer expected to control or strongly direct the activities of the team but rather to support and work with the team by acting as coach, facilitator or adviser as needed. This has important implications for the kinds of skills needed to work effectively in this new role. Managers and supervisors need to develop expert interpersonal and communication skills, but above all they need to be prepared to 'let go' and to trust their colleagues and junior members of staff. A 'command and control' approach will not work with these modern forms of teamworking and staff with experience of the traditional models will need to resist the temptation to step in at the first sign of difficulties, and also to refrain from apportioning blame if things do not work well in the early stages. The team members will need encouragement, support and help in learning from any mistakes or difficulties.

Many organisations set up self-managed or empowered teams as an important way of improving performance and they are often used as a way of introducing a continuous improvement approach. These teams tend to meet regularly to discuss and put forward ideas for improved methods of working or customer service in their areas. Some manufacturers have used multi-skilled self-managed teams to improve manufacturing processes, to enhance worker participation and improve morale. Self-managed teams give employees an opportunity to take a more active role in their working lives and to develop new skills and abilities. This may result in reduced staff turnover and less absenteeism.

Self-organising teams are usually formed spontaneously in response to an issue, idea or challenge. This may be the challenge of creating a radically new product, or solving a tough production problem. In Japan, the encouragement of self-organising teams has been used as a way of stimulating discussion and debate about strategic issues so that radical and innovative new strategies emerge. By using a self-organising team approach companies were able to tap into the collective wisdom and energy of interested and motivated employees. In the Open University, several academics may get together informally and form a self-organising team in order to share and develop the initial ideas for a new course. Participants in self-organising teams benefit from the exchange of ideas and viewpoints, and the implicit need to get things done. Self-organising teams provide a fertile learning environment and participants may acquire new knowledge, new ways of thinking and behaving, and enhanced understandings of the organisation and their role in it. Self-organising teams can play a particularly valuable role as part of an innovative organisational change programme.

2.8 Why do (only some) teams succeed?

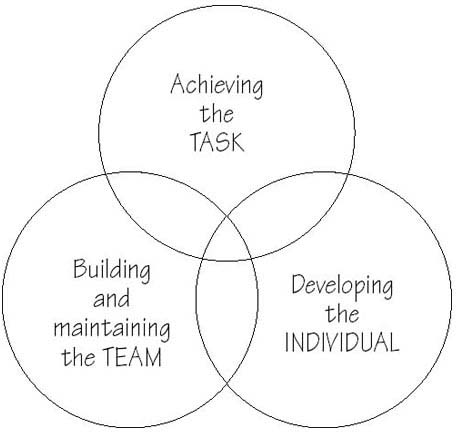

Clearly, it is not possible to devise a set of rules which, if followed, would lead inexorably to team effectiveness. The determinants of a successful team are complex and not equivalent to following a set of prescriptions. However, the results of poor teamworking can be expensive, so it is useful to draw on research, experience and case studies to explore some general guidelines. What do I mean by 'team effectiveness'? – the achievement of goals alone? Where do the achievements of individual members fit in? and How does team member satisfaction contribute to team effectiveness?

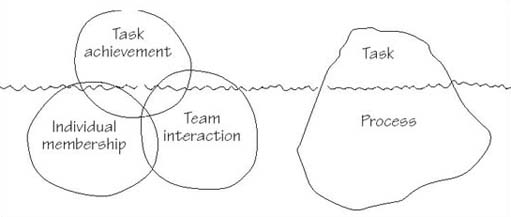

Borrowing from Adair's 1983 leadership model, the left-hand side of Figure 3 shows the main constituents of team effectiveness: the satisfaction of individual membership needs, successful team interaction and the achievement of team tasks. These elements are not discrete, so Figure 3 shows them as overlapping. For example, team member satisfaction will be derived not only from the achievement of tasks but also from the quality of team relationships and the more social aspects of teamworking: people who work almost entirely on their own, such as teleworkers and self-employed business owner-managers, often miss the opportunity to bounce ideas off colleagues in team situations. The experience of solitude in their work can, over time, create a sense of isolation, and impair their performance. The effectiveness of a team should also relate to the next step, to what happens after the achievement of team goals.

The three elements could be reconfigured as an iceberg, most of which is below the water's surface (the right-hand side of Figure 3). Superficial observation of teams in organisations might suggest that most, if not all, energy is devoted to the explicit task (what is to be achieved, by when, with what budget and what resources). Naturally, this is important. But too often the concealed part of the iceberg (how the team will work together) is neglected. As with real icebergs, shipwrecks can ensue.

For instance, if working in a particular team leaves its members antagonistic towards each other and disenchanted with the organisation to the point of looking for new jobs, then it can hardly be regarded as fully effective, even if it achieves its goals. The measure of team effectiveness could be how well the team has prepared its members for the transition to new projects, and whether the members would relish the thought of working with each other again.

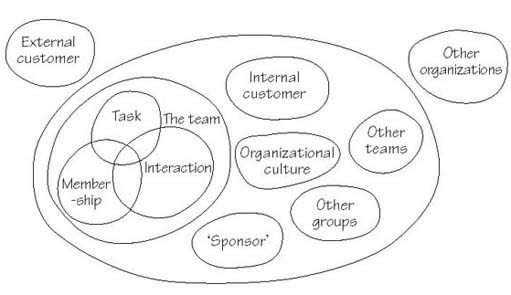

In addition to what happens inside a team there are external influences that impact upon team operations. The factors shown in Figure 4 interact with each other in ways that affect the team and its development. We don't really understand the full complexity of the nature of these interactions and combinations. The best that we can do is discuss each factor in turn and consider some of the interactions between them and how they relate to team effectiveness. For instance, discussions about whether the wider culture of an organisation supports and rewards teamworking, whether a team's internal and/or external customers clearly specify their requirements and whether the expectations of a team match those of its sponsor will all either help or hinder a team's ongoing vitality.

2.9 Conclusions

This reading has addressed four questions: what characterises a group, what characterises a team, how project teams are organised and what can make teams ineffective. Groups can be formal or informal depending on the circumstances. Work groups or teams are generally more focused on particular tasks and outcomes, and use processes that aim to achieve a unity of purpose, communication and action. I looked at six major types of team: functional, project, matrix, contract, self-managing and self-organising. Each form has strengths and weaknesses that suit particular types of project within particular organisational cultures, and teams often involve a mixture of different forms. Team effectiveness is shaped by internal influences – task achievement, individual membership and team interaction – as well as external influences, such as customers, sponsors, other teams and organisational culture.

References for Reading 1

Adair, J. (1983) Effective Leadership, Gower.

Industrial Society (1995) Managing Best Practice: Self Managed Teams. Publication no. 11, May 1995, London, Industrial Society.

Makin, P., Cooper, C. and Cox, C. (1989) Managing People at Work, The British Psychological Society and Routledge.

Stanton, A. (1992) 'Learning from experience of collective teamwork', in Paton R., Cornforth C, and Batsleer, J. (eds) Issues in Voluntary and Non-profit Management, pp. 95–103, Addison-Wesley in association with the Open University.

3 Reading 2 Working in groups

3.1 Belonging to a group

Because work groups are of central significance in the functioning of an organisation they have been studied intensively, and much has been written about group processes. In this reading it would be inappropriate to attempt to review this vast literature, which covers an enormous range of topics and aspects of groups. Instead, I focus attention here on two particular aspects of groups. First, I examine the nature of the contracts within a group: what it is that people gain from belonging to a group and, by inference, what they contribute to the group. This focus helps to explain certain characteristic problems that arise in groups. Second, I examine the process of group development.

When an individual joins a group he or she undertakes a trade-off. Joining a group requires the individual to agree to abide by the 'rules' of the group. These are sometimes explicit (such as 'who is invited to the meetings' or 'what our area of responsibility is') but often implicit (such as modes of dress, attitudes, values, beliefs, subjects that are and aren't talked about, and so on). These rules serve many purposes, a very important one of which is to distinguish the group from the rest of the world; they are the features that identify it as a group and, amongst other things, define its boundary. A group with no boundary-defining rules would include everyone and cease to be a group!

Agreeing to abide by the rules of a group involves some loss of individuality or freedom. In some groups the loss can be extreme, as in some fanatical religious groups where even questioning the leaders' authority leads to expulsion. In other groups the loss of individual freedom is minimal. In return for this loss, the individual gains not only such things as access to information and help with problem solving but also the opportunity to satisfy psychological needs, such as affiliation and security.

The nature of the agreement between the individual member and the group has close parallels with the formal, informal and psychological aspects of the contract between an employee and an organisation. In the context of a group, the 'formal contract' involves things like the group objectives, membership, leadership, terms of reference and the responsibilities of individuals within the group. The 'informal contract' includes the way meetings are conducted, how disagreements are handled, what feelings can be expressed and in what way, and so on. The 'psychological contract' involves more nebulous matters such as the degree to which the group will tolerate and handle interpersonal issues, the degree of personal disclosure that is acceptable and how much support an individual can expect from the group. It consists of all the psychological expectations of the group and of the individual. In general, the formal contract may be openly discussed in group meetings and may also be referred to in discussions about procedures. The informal contract is likely to be talked about far less and falls more into the category of 'that's just the way we do things'. The nature of the psychological contract is unlikely to be addressed except in times of crisis, such as intense disagreements or failure to accomplish some major objective. As a result, it may not be easy to discover what the psychological contracts are in a group.

One important ingredient in the psychological contract involved in joining most groups (provided that joining is voluntary) is that in return for abiding by the rules of the group one finds oneself surrounded by people who share one's perception of the world, at least to some extent. One of the key components in a good relationship is a sense of being understood and acknowledged. This can be understood in terms of individuals' need to test and affirm their sense of reality. It is possible, indeed common, to find that different people have different perceptions of the same events. By joining a group an individual agrees not to question certain assumptions about the world, and in return has the comfort of having this view of the world affirmed and reinforced.

The basic assumptions that cannot be questioned within a group form a sort of taboo area. Some of this area will be consciously known as a taboo area, while other parts will simply not be talked about. The precise relationship between the benefit of a confirmed perception of reality and the penalty associated with the taboo area varies enormously from group to group. A political group, especially a small extremist group, will usually have a large set of taboo areas: for example, members may be required to follow the party line on issues of employment, religion, sex, education, health care, foreign policy, and so on. Given the large number of taboos, it is not surprising to find that such groups repeatedly go through the process of dividing into factions. Although this is a fairly extreme example, the same processes operate in formal and informal work groups. For example, in the production of an Open University course there comes a point when it is essential that the members of the course team agree to the basic course aims and cease to raise fundamental questions of principle. If a team failed to reach such agreements, this could have very serious knock-on effects.

Another common ingredient in the psychological contract involved in belonging to a group is the emotional trade-off. Just as a group reinforces certain aspects of a particular view of reality, so too is it likely to reward certain types of behaviour and emotional expression whilst disapproving of others. For example, many political groups provide their members with a forum for expressing feelings of hatred or derision, provided of course that they are directed towards 'the opposition'. As in the case of group perceptions and taboo areas, less extreme requirements exist in typical formal and informal work groups. It is common to find work groups providing a forum for expressing positive and negative judgements of others' worth, for encouraging aggressiveness (as in sales promotion) or defensiveness. Another form of emotional trade-off often occurs around the issue of security. For example, members of an informal work group may agree among themselves to work at a particular rate, to gain some measure of security against undue pressure from supervisors.

In general, the trade-offs involved in belonging to a group will be balanced: the more an individual gives up in joining the group then the larger the pay-off expected. The level of trade-off involved, that is the size of the pay-offs and commitments, will strongly influence the group's ability to change. A group with very large pay-offs will resist change unless all the group members can see the prospect of an equivalent pay-off in the new arrangement. Exploring the resistance to change can be a powerful way of uncovering the important features of the contracts between an individual and a group.

Activity 3

Identify a team that you belong to, and list some changes to the team or its activities that you might conceivably be asked to make. Arrange them in order, from changes you would find very easy to accept to changes that you would find very hard to accept.

To what extent is this difference determined by what the proposed change would 'cost' you and what your 'pay-off' from it would be?

So far, the emphasis in the discussion has been on the group as a collection of individuals. It is also possible, and productive, to regard the group as a psychological entity in its own right. The concepts of self, self-concept, self-esteem and psychological energy that we normally apply to individuals, can to some extent apply to groups as well.

However, although this analogy is productive, it also has its limits. One important difference is in the levels of 'self-awareness' between individuals and a group. So far, I have assumed implicitly that everything that the individual member knows about the group, and that the group knows about the individual member, is shared by both parties. In fact this is not usually the case: for instance, there will often be 'hidden agendas' – things that an individual wants or expects from the group, but that the group doesn't know about. Common examples of hidden agendas are:

Someone using a committee meeting as an opportunity to impress the boss.

An individual raising an issue at a meeting in order to embarrass or force the hand of another member of the group.

Someone resisting a proposal for reasons they are not prepared to disclose (and thus being forced to invent spurious grounds for resisting).

There may also be things that the group knows about individual members which the individuals are unaware of themselves: that is to say, individual members may have what are termed 'blind spots'. For example, a member of a group makes a suggestion, which if accepted by the group requires some action to be taken. None of the rest of the group believes that the person making the suggestion is capable of carrying out the action needed, and consequently the suggestion is rejected. The person making the suggestion is aware of the decision but unaware of the reason behind it.

Both hidden agendas and blind spots impede the effective functioning of a group. In fact, it has been shown that their effect on group performance is much larger than one would intuitively guess. There is no simple explanation as to why this should be so. But it appears that small increases in a group's self-awareness (that is, the removal of hidden agendas and blind spots by encouraging the development of greater openness and trust) can release a disproportionately large amount of psychological energy, which would otherwise have been absorbed by defensive and protective checks and manoeuvres.

3.2 Group processes

So far, the emphasis has been on the factors that are significant in the relationship between an individual and the group. In this section I examine such issues as what tasks the group has to perform, how big the group is, who should be in it, how the group develops and so on. These are particularly important issues in the operation of formal groups within the organisation. These factors, mostly associated with the 'environment' of the group, can be critical in determining how effective a group is, both in accomplishing tasks and in a psychological sense.

3.2.1 Group context

Probably the two most important features of a formal work group are the task or objectives assigned to it and the environment in which it has to carry that task out. It is important that a work group be given a realistic task and access to the resources required to complete it, and that the people in the group feel that the task is worth accomplishing, i.e. that it has some importance.

When a group fails to make headway, one common cause is that its brief covers several tasks, some of which require members to take up different roles. For example, a management group may be given the tasks of analysing why the introduction of a new information system has gone wrong and designing a new one. In the analysis of what has gone wrong the members of the group, as representatives of their departments or subgroups, may adopt generally defensive postures. Once defensiveness has been established as the group dynamic, it will be virtually impossible to establish the sort of cooperative and free-wheeling dynamic that is required in a creative group. There will be a tendency for managers to keep their departmental hats on and maintain their defensive postures. A simple solution to this sort of problem is to constitute two separate groups or committees. These may well have identical membership. However, by meeting under a different name, with different objectives and, preferably, in a different place, the participants are freed to create a new dynamic, one appropriate to the second task.

3.2.2 Group size

Another significant feature of a work group is its size. To be effective it should be neither too large nor too small. As membership increases there is a trade-off between increased collective expertise and decreased involvement and satisfaction of individual members. A very small group may not have the range of skills it requires to function well. The optimum size depends partly on the group's purpose. A group for information sharing or decision making may need to be larger than one for problem solving.

A simple calculation can indicate how quickly the number of two-way interactions in a group increases with increasing size. In a group of N people (where N stands for a number) each of the N individuals relates with N × 1 others, so there are N × (N − 1) / 2 possible interactions.

In many organisations, there is a tendency to include representatives from every conceivable grouping on all committees in the belief that this enhances participation and effectiveness. There is also the view that putting a representative of every possible related department into a given group helps smooth information flow and project progress. In practice, communication is usually reduced in larger groups. As the group size grows, members feel less involved in the process, alienation tends to increase and commitment to the project tends to decrease. The numbers most commonly quoted for effective group size in a face-to-face team are between 5 and 10, so reducing the number of interactions and lessening the risk of conflict.

There is a nice demonstration that the 'between 5 and 10' rule is due to communication limitations. If we devise special procedures to manage the interpersonal exchanges (as in some computer-based brainstorming systems, where the computers handle all the gathering and feeding back of ideas) the advantages of the small group disappears: the larger the group, the more ideas are generated.

However, in the normal face-to-face mode, if there are more than about 12 members in our team we are likely to encounter group-size problems. If the numbers cannot be reduced we might consider restructuring the team into sub-groups and delegating responsibility for achieving some of the team's objectives. We may find that if we don't do this deliberately it will happen anyway. For instance, members who like each other or share common interests may spontaneously form sub-groups.

Unfortunately, the breakdown of large groups into sub-groups and cliques may not help a team achieve its goals. One device for keeping large numbers of people informed about a project is for a small group to manage the task and for it to invite relevant people to attend particular meetings. Alternatively, the small group can arrange to give information seminars to larger groups of colleagues. So, for the purposes of achieving team goals it is better that the process of restructuring big groups into smaller groups is managed consciously and carefully.

3.2.3 Managing group membership

The range of people that makes up the membership of a team, and the relationships they have with each other, have great influence on the team's effectiveness. The members should all be able to contribute their skills and expertise to the team's goals to make the best use of the resources. If you are ever in the position of being able to select your own team, you will need to identify your objectives and the methods for achieving your goals. From this will come the competences – the knowledge, understanding, skills and personal qualities – which you need in your team members.

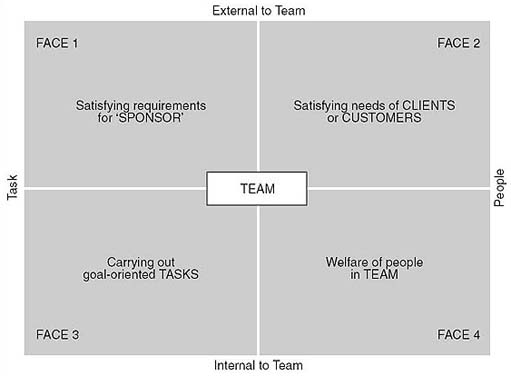

It is important to appraise as systematically as possible the relationship between team functions and required competences in order to identify gaps and begin to allocate responsibilities, organise training and so on. Figure 5 provides a useful way of weighing up the mixture of 'task' and 'people' functions (or 'faces') of a team.

Faces 1 and 2 are external to the team and concern:

adapting to the environment and using organisational resources effectively in order to satisfy the requirements of the team's sponsor.

relating effectively with people outside the team in order to meet the needs of clients or customers, whether internal or external to the organisation.

Faces 3 and 4 are internal to the team and concern:

using systems and procedures appropriately to carry out goal-oriented tasks.

working in a way which makes people feel part of a team.

Each face implies different competences.

We may find that when we are setting up a team we have to guess a little about the competences that are required. We may also find that as the team develops and gets on with its work, there are changes in everyone's perception of the skills and knowledge needed. It is therefore important to keep an eye on changes that affect the expertise needed by the team and actively recruit new members if necessary. It is frequently the case that team members have other work commitments outside the team. The implications of this should be taken into account when recruiting team members and allocating tasks and responsibilities to them. Team loyalties and commitments need to be balanced with other loyalties and commitments. Often we will have limited or no choice about who is recruited to the team. We may find that we just have to make do with the situation and struggle to be effective despite limitations in the competence base.

As well as competencies there are other factors that can influence the working of a team. The balance of men and women and people from different nationalities or cultural backgrounds all play a part. Differences in personality can also have a significant effect. Achieving the best mix in a team invariably involves working on the tensions that surround issues of uniformity and diversity. The pushes and pulls in different directions need to be managed. The dismantling of many of the restrictions in the European labour market supports moves towards recruitment practices which seek team members with proven capabilities to work in other countries. Legislation and social changes make it easier for organisations to develop and train their staff to appreciate ethnic and national differences in values, style, attitudes and performance standards. Nevertheless, there are countervailing tendencies, internally and externally.

Developing openness and trust, for example, can often seem easier in the first instance on the basis of a high degree of homogeneity; strengthening diversity can seem threatening in an established team.

3.2.4 Functional and team roles

When individuals are being selected for membership of a team, the choice is usually made on the basis of task-related issues, such as their prior skills, knowledge, and experience. However, team effectiveness is equally dependent on the personal qualities and attributes of individual team members. It is just as important to select for these as well.

When we work with other people in a group or team we each bring two types of role to that relationship. The first, and more obvious, is our functional role, which relies on the skills and experiences that we bring to the project or problem in hand. The second, and often overlooked, contribution is our team role, which tends to be based on our personality or preferred style of action. To a large extent, our team role can be said to determine how we apply the skills and experiences that comprise our functional role.

Belbin (1981 and 1993) researched the functional role/team role distinction and its implications for teams. He found that, while there are a few people who do not function well in any team role, most of us have perhaps two or three roles that we feel comfortable in (our so-called 'preferred roles') and others in which we feel less at ease (our so-called 'non-preferred roles'). In fact, Belbin and his associates identified nine such team roles. Some of the non-preferred roles are ones we can cope with if we have to. However, there are also likely to be others in which we are both uncomfortable and ineffective.

Belbin's nine team roles are listed in Table 3. It is worth noting that all nine are equally important to team effectiveness, provided that they are used by the team at the right times and in an appropriate manner.

When a team first addresses a problem or kicks off a project, the basic requirement is usually for innovative ideas (the need for a 'plant'), closely followed by the requirement to appreciate how these ideas can be turned into practical actions and manageable tasks (the 'implementer'). These steps stand most chance of being achieved if the team has a good chairperson (the 'coordinator') who ensures that the appropriate team members contribute at the right times. Drive and impetus are brought to the team's activities by the energetic 'shaper'. When delicate negotiations with contacts outside the team are called for, it is the personality of the 'resource investigator' that comes into its own. To stop the team becoming over-enthusiastic and missing key points, the 'monitor/evaluator' must be allowed to play a part. Any sources of friction or misunderstanding within the team are diffused by the 'teamworker', whilst the 'specialist' is used for skills or knowledge that are in short supply and not used regularly. The 'completer/finisher' ensures that proper attention is paid to the details of any solutions or follow-up actions.

It is essential that team members share details of their team roles with their colleagues if the team is to gain the full benefit from its range of roles; the team can then see if any of the nine team roles are missing. If this is the case, those team members whose non-preferred roles match the missing roles need to make the effort required to fill the gap. If not it may be necessary to bring in additional team members. Clearly, this sharing calls for a degree of openness and trust, which should exist in a well-organised, well-led team. Unfortunately, in teams that have not yet developed mutual trust and openness, some people who may be quite open about the details of their functional roles tend to be somewhat coy about sharing personality details. A competent leader will handle this situation in a sensitive manner.

| Team role | Team strengths | Allowable weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Plant | Creative, imaginative, unorthodox | Weak in communication skills |

| An innovator | Easily upset | |

| Team's source of original ideas | Can dwell on 'interesting ideas' | |

| Implementer | Turns ideas into practical actions | Somewhat inflexible |

| Turns decisions into manageable tasks | Does not like 'airy-fairy' ideas | |

| Brings method to the team's activities | Upset by frequent changes of plan | |

| Completer-finisher | Painstaking and conscientious | Anxious introvert; inclined to worry |

| Sees tasks through to completion | Reluctant to delegate | |

| Delivers on time | Dislikes casual approach by others | |

| Monitor-evaluator | Offers dispassionate, critical analysis | Lacks drive and inspiration |

| Has a strategic, discerning view | Lacks warmth and imagination | |

| Judges accurately; sees all options | Can lower morale by being a damper | |

| Resource investigator | Diplomat with many contacts | Loses interest as enthusiasm wanes |

| Improviser; explores opportunities | Jumps from one task to another | |

| Enthusiastic and communicative | Thrives on pressure | |

| Shaper | Task minded; brings drive to the team | Easily provoked or frustrated |

| Makes things happen; pressurises | Impulsive and impatient | |

| Dynamic, outgoing and challenging | Intolerant of woolliness or vagueness | |

| Teamworker | Promotes team harmony; diffuses friction | Indecisive in crunch situations |

| Listens; builds on the ideas of others | May avoid confrontation situations | |

| Sensitive but gently assertive | May avoid commitment at decision time | |

| Coordinator | Clarifies goals; good chairperson | Can be seen as manipulative |

| Promotes decision making | Inclined to let others do the work | |

| Good communicator; social leader | May take credit for the team's work | |

| Specialist | Provides rare skills and knowledge | Contributes only on a narrow front |

| Single-minded and focused | Communication skills are often weak | |

| Self-starting and dedicated | Often cannot see the 'big picture' |

Managers sometimes try to rationalise having teams that are unbalanced in a team-role sense by claiming that they have been assigned a group of people as their team and they must live with it. In most of today's workplaces there is a steady and regular movement of staff in and out of management groups and departments. When selecting or accepting new people into their groups or departments, managers with an understanding of team-role concepts will look for team-role strengths in addition to functional-role strengths.

Each team role brings valuable strengths to the overall team (team strength), but each also has a downside. Belbin has coined the phrase 'an allowable weakness' for what is the converse of a team strength. The tendency is for a manager to try to correct perceived weaknesses in an employee. But by doing this with allowable weaknesses we face the possibility of not only failing to eradicate what is after all a natural weakness, but also risking undermining the strength that goes with it. This is not to suggest that weaknesses should not be addressed. The point is that any attempts at improvement should be kept in balance and we should be prepared to manage and work around the weaknesses of our team colleagues and ourselves. Many people put on an act in an attempt to hide their weaknesses. Once they see that they can admit to them without prejudice, they feel a sense of relief and are ready to play their part in the team in a more open manner.

Activity 4

Consider a recent meeting you have attended. Identify two or three of Belbin's team roles that best fit your perception of your role in the meeting.

Try asking a colleague you know well who also attended the meeting for his or her perception of your team role(s).

What are your 'allowable weaknesses'? What could you do in a meeting to compensate for them?

3.2.5 Group development

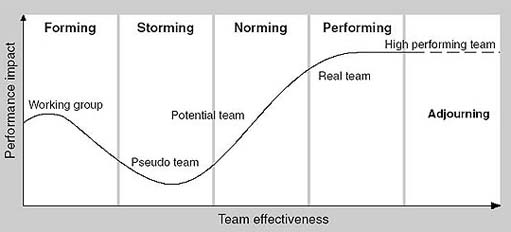

Next on the list of priorities in the functioning of groups is the process of group development. One popular conception of the way in which groups 'gel' and become effective was first suggested by Tuckman (1965) and then extended by Tuckman and Jensen (1977). Tuckman originally identified four stages in this development process, which he named 'forming', 'storming', 'norming' and 'performing'. These stages (see Figure 6) can be summarised as follows:

Forming

The group is not yet a group but a number of individuals. At this stage, the purpose of the group is discussed, along with its title, leadership and life span. Individuals will be keen to establish their personal identities in the group.

Storming

Most groups go through a stage of conflict following the initial, often false, consensus. At this stage, purpose, leadership, roles and norms may all be challenged. Personal agendas may be revealed and some interpersonal hostility is to be expected. If successfully handled, this stage leads to the formulation of more realistic objectives and procedures. It is particularly important in the formation of trust within the group.

Norming

During this stage the group members establish the patterns of work and norms for the group. What degree of openness, trust and confidence are appropriate? At this stage, there will be a lot of tentative experimentation by individuals testing the climate of the group and establishing their levels of commitment.

Performing

Only when the previous three stages have been successfully completed will the group be able to be fully and sensibly productive. Although some kind of performance will be achieved at all stages prior to this phase, output will have been diminished by the energy put into resolving the group processes and by the personal hidden agendas. In many periodic committees the basic issues of objectives, procedures and leadership are never resolved and continue to plague the group in almost every meeting, leading to frustration and substantially reduced effectiveness.

To these four stages were later added a fifth stage:

Adjourning or mourning

The phase when a team eventually disbands, having completed its task, is also characterised by distinctive processes. Members may face significant uncertainties as they move away to new challenges. They may need feedback on how well they have done, what they have learned and how they are likely to cope with new challenges. The team leader may need to minimise the stress that is associated with changes and transitions. The team members may be feeling some sadness if their experiences within the team were particularly satisfying. If appropriate, the team leader may encourage the team members to maintain links with each other and develop their relations through new activities and projects.

It is in the nature of the team development process that people need to exercise considerable sensitivity and judgement. There is an understandable tendency to think that we must always be actively intervening to move the process along, and exercising the appropriate team development skills. Very often, however, this is not the best course of action. An appreciation of team dynamics and the ability to 'read the situation' may suggest that a lightness of touch is called for. Far from intervening and trying to make things happen, the requisite skill is that of detachment. Team cohesion and productive norms can often be nurtured most effectively by turning attention elsewhere. We need to be able to judge when it is appropriate to work directly and intensively on teambuilding and when it is best to allow the processes to occur less consciously. As Stanton (1992) discovered, teams which persistently give undue attention to their own development often end up being unproductive – and, indeed, generally unsatisfactory for their members.

In a group in which the task is clearly defined and regarded by everyone as highly important, the first three stages of the development process may initially be dealt with during the first meeting and some degree of consensus reached about how best to proceed. However, for most groups these stages will take time to work through or will recur from time to time. The stages may overlap, operate concurrently or be repeated, as old issues resurface or new problems appear. When people leave a group and/or new members join, the cycle may start again. Sometimes quite violent storming can occur at this time if the new members are strong personalities and raise issues that have previously been suppressed. The acceptance and appropriate handling of the storming phase is particularly important. If ignored, the disagreements and hostilities will be regarded as unacceptable and this will undermine the group's performance. The issues will still be discussed, however, and this discussion may go on outside the formal meetings in the form of politicking and the formation of cabals, thus further undermining the development of the group. In many organisations it is recognised that it takes time for a group to form and that this time should be included in the scheduling of projects and programmes. Many organisations also make use of team-building exercises and training programmes to encourage team members to work together more effectively.

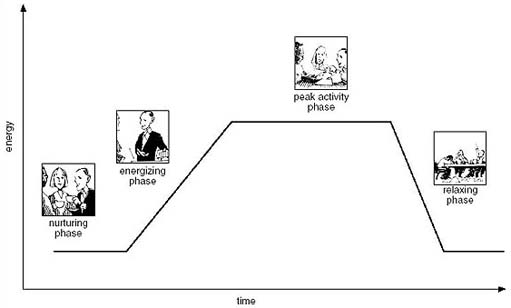

3.2.6 The creative cycle

The creative cycle refers to the cycle of development that takes place within a single meeting of a group, as opposed to the longer-term cycle just described which may occur over many meetings. As in the case of the longer-term cycle, the creative cycle can be thought of as occurring in four phases: nurturing, energising, peak activity and relaxing (Figure 7).

Groups which function well usually have some sort of intuitive understanding of this cycle and have evolved a way of working that synchronises their work to the rhythm of their own creative cycle. Formal groups often fail because they fail to recognise the existence of this cycle or try to leave out one or more stages. For example, many committees and formal groups do not acknowledge the nurturing phase and get down to business as soon as all the members are present. These groups may find that their meetings are stiff and unproductive, and that they never really get going. A simple device for establishing this stage is to arrange for coffee or some form of refreshment prior to the business and to encourage members to use the time to mix informally with each other. Another device is to deal with the less important or routine matters during this 'warm up' period. If the main business of a meeting is the first item on the agenda then the proceedings may be slow and unproductive, because the energising phase has been missed out. There is an appropriate time for everything in a meeting, and people who are successful at handling meetings have an intuitive feel for this. The main business should be tackled once the group is energised, not any earlier and certainly not after the peak activity phase has been passed. (The most reliable indicator of a group's energy state is how any particular member feels at the time.) It is important to recognise the relaxing phase. If business is introduced into this stage, it will be cursorily dealt with and may even undo some of the work done earlier. Furthermore, meetings ended too quickly, before the relaxing phase is completed, will leave members with a sense of dissatisfaction or incompleteness. As the pace of organisational life quickens there is increasing pressure on managers to rush from one meeting to the next, to start and finish at peak performance, often to the detriment of the effectiveness of the meeting.

3.2.7 Ways that groups go wrong

Before leaving Reading 2, it is worth mentioning some of the characteristic ways that groups 'go wrong'. Why should a group, asked to design a camel, produce a horse? You might expect that when we pool the talents, experience and knowledge of a group, the result would be better, not worse, than that of any individual member. But as groups design 'horses' so frequently there must be some fairly familiar decision-making processes at work. Probably the most common problems are those that have already been discussed: unclear objectives, multiple tasks, the size and balance of the group, and non-completion of the stages of group development. However, there are other factors that don't fit easily into these categories. One such factor is what is termed 'groupthink'.

Groupthink is a process whereby a group collaborates systematically to ignore evidence suggesting that what it has done, or is planning to do, is ill advised. It is like a giant blind spot operating on the whole group. An example of groupthink is given in Box 2.1.

Box 2.1 Example of groupthink

Twelve people joined a group to help them give up smoking. On joining, each agreed to observe two rules: to make an immediate and conscientious effort to give up smoking, and to attend every meeting. At the second meeting of the group two of the most dominant members took the position that heavy smoking was an almost incurable addiction. The majority of the others soon agreed that no-one could be expected to cut down drastically. One heavy smoker took issue with this consensus, arguing that by using willpower he had stopped smoking since joining the group, and that everyone else could do the same. Most of the others ganged up against the man who was deviating from the group consensus. Then, at the beginning of the next meeting, the deviant announced that he had made an important decision:

I have learned from experience in this group that you can only follow one of the rules [try to give up, and attend all meetings], you can't follow both. And so I have decided that I will continue to attend every meeting but I have gone back to smoking two packs a day and I will not make any effort to stop smoking again until after the last meeting.

Whereupon the other members beamed at him and applauded enthusiastically, welcoming him back to the fold. No one commented on the fact that the whole point of the meetings was to help each individual to cut down on smoking as rapidly as possible.

Groups affected by, or perhaps it would be better to say infected by, groupthink make bad decisions in four main ways:

They make decisions that subvert their own official goals (as in Box 2.1). Faced with a decision where the achievement of those goals conflicts with the preservation of easy-going unanimity in the group, the official goals go out of the window.

They don't test their decisions by considering information or opinions that contradict them or which point to substantial difficulties in implementing the decisions. Indeed, in the grip of groupthink, they often take care to screen out awkward facts or ideas. Hence, they are often surprised when their decisions do not work out as they hoped.

There is a well-documented tendency for such groups to take more risky decisions than any individual member would take, or believe to be warranted. This is generally called the 'risky shift'.

They have a disturbing tendency to make decisions that treat others as 'the enemy'. This can result in groups paying others scant consideration and respect, a fact that is particularly pernicious and accounts for some of the worst excesses of discrimination against other groups, distinguished on the basis of race, creed or gender.

So much for the need to take groupthink seriously; how can we tell if a group is suffering from it? Fortunately, there are a number of indicators that help us to diagnose groupthink:

First, some groups are especially vulnerable. I have already mentioned that it is most often found in groups that are friendly and collaborative; more precisely, they are rather cosy. The group has settled into a habit of discouraging and frowning on overt disagreement and conflict. When that is the case, individual members are more ready to suppress divergent ideas and, more powerfully, less inclined to think hard about whether or not they really agree with what is being decided.

Second, groups which have a certain prestige, and regard themselves as an elite group in some way, are also particularly susceptible. Groups which are at the head of some hierarchy often feel this way about themselves. The hierarchy doesn't have to be as large as a big company or a hospital – management committees of clubs or local associations are often the worst afflicted.

Finally, some groups are well insulated from opinion that might correct false assumptions and misperceptions. Design teams often manage to get themselves into this position, sometimes deliberately because what they are doing is a close commercial secret, and sometimes by accident because they can't be bothered to undertake the lengthy business of explaining what they are doing to an outsider. The leaders of public-interest groups can easily get themselves into this position too – remote from a body of members who pay subscriptions and get a newsletter, and with few opportunities to comment on the decisions of the leaders.

More precise indicators come from the way the group goes about its work. In all groups the leader has a key role in establishing the processes and procedures of the group; he or she usually has the advantages of expertise, status, control of the agenda, and the power to distribute or withhold benefits to the members. If the leader uses these advantages to state preferences and propose a particular decision right from the outset of a discussion, it will be hard for other members to resist. A more sophisticated variant of this is when the leader announces that the group has to decide between a limited range of options, usually two. This gives the appearance of allowing genuine discussion, but has the effect of limiting the group's focus of attention in much the same way. With leadership of this kind, especially in a cohesive group, it will be easy to slide into groupthink.

The last indicator of groupthink is the one that should flash the loudest warning signals: it is the feeling of unbounded optimism, even euphoria. The group feels immensely proud of itself, and feels sure that it can overcome all the problems and lead the way to a bright new future. As all the members agree, each feels that what they have decided must be right. In these circumstances it is not just unpleasant to spoil things by taking a hard look at the limits of the group's power and the damage that might be done if it is wrong, it is also seen as rank disloyalty.

The second process whereby groups can go wrong involves seeking internal or external scapegoats. It is usual to find groups making a scapegoat of either the weakest member or the group leader. In other cases the group blames people external to the group for not doing their job or providing the appropriate resources for the group to be successful. In the latter case this external blaming is a blind spot. However, blame solves nothing and only serves to perpetuate the mistakes made.

Both of the processes described above are examples of groups resisting change in some sense. Where a group has not functioned effectively, then its first response is likely to be to defend itself, just like an individual. Under these conditions it adopts a 'fight-or-flight' attitude and this dominates the operation of the group. Ignoring evidence or blaming individuals are simply devices for resisting facing up to the need for change. Groups resist change for all the same reasons that individuals resist change – it is uncomfortable and potentially painful. This is accentuated in a group in which the individuals have very strong psychological contracts, that is, where the members have strong investments in the group. If the psychological contracts are largely unconscious, the group will probably have invented some rationalisation to explain its functioning. Before such a group can change its operation, it will need to give up this rationalisation and examine the psychological issues beneath it. This involves a more substantial change than the group can easily handle; it is a second-order change, involving a change in structure as well as objective.

3.3 Conclusions

The main points made in this reading have been:

Groups cannot be understood simply in terms of the interactions between individual members because:

individuals have contracts with the group as a whole and this is distinct from their relationships with other members of the group on a one-to-one basis;

people behave differently in groups;

there are simply too many possible interactions between group members, including their sub-personalities, to make sense of group activity in this way.

The contracts that an individual has with a group may have several components, each of which may have conscious and unconscious parts. The main components are likely to include:

certain ideas, attitudes or beliefs that support a particular perspective or view of the world;

an emotional component, relating to certain values and the expression or denial of certain emotions.

People are most likely to function effectively as a group if:

the group has a well-defined task that is seen as challenging and significant by group members;

the group is not too large (has fewer than 10 members) and not too small (too small to have adequate resources and expertise);

the expertise and characteristics of members of the group are complementary;

the group allows itself time to go through the stages of development – forming, storming, norming and performing – and by doing so, develops trust by sharing hidden agendas and personal differences;

each meeting is designed to allow for a creative cycle that involves nurturing, energising, peak activity and relaxation;

the group explicitly discusses its objectives, how to organise itself, its leadership and the roles of members.

SAQ 1

Construct your own brief definitions or descriptions of the following:

(a) The informal contract between a group and one of its members.

(b) The psychological contract between a group and one of its members.

(c) Hidden agenda.

(d) Blind spot.

Answer

Your definitions should include at least the following features:

(a) Informal contract: not usually written down or discussed; includes assumptions about ways of working, what feelings can be expressed and in what ways. Taboo areas may be included.

(b) Psychological contract: the set of psychological expectations that the group has of the individual and vice versa; not discussed and only revealed in a crisis.

(c) Hidden agenda: an item known to a group member but not to the group as a whole.

(d) Blind spot: a characteristic or aspect of an individual recognised by the group, but not by the individual, involved. (Deep down, the individual may know about it but refuse to acknowledge it.)

SAQ 2

Calculate the number of interactions in groups with four, six, and eight members.

Answer

The formula is N × (N − 1) / 2.

With four members there are six possible pairings (AB, AC, AD, BC, BD, CD). With six there are 15 possible pairs. With eight there are 28 possible pairs. The number of possible interactions (and hence possible conflicts or misunderstandings) nearly doubles in going from a group of six to a group of eight.

SAQ 3

From your study of Reading 2, make a list of the four or five factors that you regard as most significant in determining whether or not a group will function effectively.

Answer

The most important factors are:

worthwhile, clear, and attainable group objectives.

group size and composition: it should be neither too big nor too small, and should include people with complementary skills and characteristics.

adequate time to go through the stages of group formation, especially the storming phase.

organisation of group meetings so that the stages of the creative cycle are each given adequate time.

Another important factor is the group's attitude to change. However, if the above items are all satisfied, then this, along with other factors, will probably get sorted out satisfactorily. In particular, if the group succeeds in generating trust in the process of group formation, then blind spots and hidden agendas will not be a major source of difficulty (since individuals will share them with the group).

Key for SAQs 4 and 5

The following paragraphs provide short descriptions of five different groups.