Reading and note taking – preparation for study

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 19 April 2024, 2:57 AM

Reading and note taking – preparation for study

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

recognise some of the skills which are particularly associated with the way social scientists work

describe some basic techniques relating to reading, for example, highlighting, note-taking and the processing

write in your own words using references and quoting sources.

Introduction

This course is about the very basic study skills of reading and taking notes. You will be asked to think about how you currently read and then be introduced to a some techniques that may help you to alter the way you read according to the material you are studying. In the second section you will be asked to look at some useful techniques for note taking and how you may apply them to the notes you make.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of Level 1 study in Sociology.

1 Reading and note taking

1.1 Preparation for study

One of the main purposes of this course is to help you develop two kinds of skills:

the general skills of being a student

some skills which are particularly associated with the way social scientists work.

Both are of fundamental importance to your success in studying other courses. This course is about the very basic study skills of reading and taking notes. These are basic in the sense that they are the foundation for all successful study. But that does not mean they are simple.

If you have no recent experience of reading academic texts you need to re-learn your reading skills. Reading magazines, newspapers or fiction is a useful basis, but entails very different skills from academic reading. The same goes for taking notes. Scribbling down the important bits of a recipe from a television cook or underlining some interesting advice from a magazine article helps, but of course there is a lot more to taking notes from a social science text. So we suggest that you spend the time working on these skills. Then, when you need to use these skills, you will be able to use them quickly, effectively and with more confidence.

In Sections 1–3 of this course we:

ask you to think about how you read now by testing yourself on a piece of everyday reading matter,

introduce you to some basic techniques for adjusting your reading to suit the purpose you have in mind, and

focus on some of the more common problems that students may experience when reading unfamiliar material and suggest some possible ways of dealing with them.

In Sections 4–8 we focus on techniques of:

highlighting,

note taking and shorthand,

processing information and interrogating key ideas,

writing in your own words, and

referencing and quoting sources.

In the final sections we focus on newspapers, and provide a number of activities to get you thinking critically about the press as a source of ideas, information and evidence.

This course is organized around a series of activities which focus on articles and extracts from a range of sources, including textbooks and newspapers. The articles chosen focus on crime and are pitched at about the same level as the materials you will work with on an introductory level course.

However confident you are about being an effective reader and an effective note taker, we suggest that you take some time to work through what follows. If it really is very familiar, keep moving quickly on to the next activity. You might find you complete the whole thing in a couple of hours, or you might spend weeks working through it – especially if you have time to follow up our suggestions for finding other pieces of material and practising on them. It really is up to you. We hope you find it useful.

1.2 How do you read?

A good way of getting started on developing your reading and note-taking skills is to think about how you read now.

Activity 1

The short extract reproduced below is taken from The Scotsman and is a journalistic piece of writing, rather different from something you would read in a social science textbook. It focuses on a ‘child curfew’ scheme introduced in Hamilton, Lanarkshire in October 1997. Read through the extract and then:

Jot down any feelings and thoughts you had about the content of the article: for example, did you feel that the idea of a child curfew scheme was a good one or did you have reservations about it?

Think about how you read it: did it take you a long time to read?, did you read it straight through or did you have to stop and go back at intervals?, did you read each word individually or were you able to move more quickly, getting the general gist of the ‘story’?

You will find our feedback and comments noted in the "Now read the discussion" link beneath the article. Try not to read these until you have completed the activity.

Hamilton child safety curfew to be extended

Calls for scheme to go national, despite rise in crime on estates where trial held

Jim Wilson

The expansion of the so-called child curfew in Hamilton was announced yesterday as the Government called for the controversial scheme to be copied across Scotland.

The operation will now cover the whole of the Lanarkshire town, despite official research suggesting that crime rose in the three housing estates where it was launched a year ago.

The extension of the initiative, in which children out after dark are taken home, was announced as Strathclyde Police and the Scottish Office released analysis suggesting the community patrols have overwhelming support in the town.

Opinion polls in Hamilton, including one run by a local newspaper, revealed more than 90 per cent backing for the curfew, although more than half of all children thought police did not understand youngsters and stopped them for no reason.

Yesterday, the Scottish Office urged the other seven Scottish forces to copy the curfew, despite critics claiming the operation is unnecessary and heavy-handed.

No other Scottish force has voiced any interest in adopting a similar strategy but Henry McLeish, the Scottish Office home affairs minister, said every town and city could benefit. He said chief constables must decide their own operational strategies, but the success of the initiative in Hamilton could not be questioned and promised to send the new analysis to every force and police board.

‘I would be delighted to see this initiative copied and developed elsewhere,’ he said.

‘This should be the start of a huge debate about how best to reclaim our communities for decent, ordinary people.’

Research, commissioned by the Government and carried out by Stirling University, looked at the first six months of the operation, October 1997 to April 1998, and revealed that reported crime in the chosen estates fell by 23 per cent compared with the previous six months.

However, researchers concede seasonal trends meant more crimes are committed in summer and, when compared with the same six months of the year before, reported crime actually rose on the estates of White-hill, Hillhouse, and Fairhill, by 17 per cent.

In addition, a survey in Hillhouse revealed that, while 44 per cent of people felt safer since the curfew was launched, a rising number of residents, 84 per cent, would not now enter certain areas of the estate.

Critics claim police should already be protecting very young children and Save the Children in Scotland fears the rights of young people could be violated. Yesterday, the charity's director, Alison Davies, said the research demanded careful scrutiny. ‘The figures and factors underpinning the research must be studied closely’.

The Government is keen for the Hamilton scheme to be a template for adoption by forces across Britain, but John Orr, the Strathclyde chief constable, conceded the research was not wholly supportive.

He stressed, however, that complaints to the police had fallen by 20 per cent in the pilot areas while the initiative, which will be continued as a pilot project for another year, had won backing from parents, children, and traders.

He said the scheme had been misrepresented as a curfew intended to reduce crime, but had instead been driven by the need to protect vulnerable children and encourage their parents to take more responsibility.

He said: ‘The suggestion that officers are going around like dog-catchers snatching children off the streets is simply wrong. There has not been a single complaint about the initiative and it has clearly been given the community's seal of approval.’

Mr Orr said the number of community officers involved in the expanded initiative would have to be doubled, possibly trebled, from the two teams of six currently involved.

A total of 280 children have been returned home over the past year. Five were charged with offences. Seventy per cent were boys, 14 per cent were aged under eight years old, and almost ten per cent were drunk. Sixty-one children have been taken home in the last six months compared with 221 in the first half of the trial, and officers believe the reduction indicates that more parents are taking responsibility for their children.

Allan Miller, the director of the Scottish Centre for Human Rights, said there was legitimate scepticism concerning crime figures and claimed the research proved only that treating all youngsters as potential criminals is not the answer. He said ‘The statistics on crime complaints and safety perceptions are mixed if looked at on the whole. For the police, the lesson should be to listen to and understand young people and to recognise their needs and rights.’

Mr Miller said 77 per cent of the children taken home by police were aged 12 to 15 and had done nothing wrong. He said it was significant the scheme had been renamed since being launched to include the protection of youngsters.

Meanwhile, South Lanarkshire Council yesterday announced the opening of a new £3 million centre for young people as part of the increased provision of youth facilities.

Discussion

Thinking and asking questions about both what you read and how you read is a useful way of becoming more aware of what your strengths are and what you may need to work on in order to develop your skills further. You might have found that you took quite some time to get through the article and that you were reading each word individually. Reading words one by one can slow you down. One way you might try to speed things up is to look beyond the single word and let whole lines float into your brain. This makes for a more fluent process and you will probably find that you are more able to get the gist of an argument this way than if you consciously take one word at a time. Of course, if you come across an unfamiliar idea or concept you might need to slow down again or even go back over a sentence or two a couple of times. The point is that you can vary how you read depending on what you are reading. Indeed, becoming more aware of how you read more generally will help you to think about alternative methods to adopt when you are reading with a specific purpose in mind, be that gleaning an overview of an extract or argument or extracting detailed points and ideas from a book chapter.

1.3 Active reading

Whatever the specific objective of reading, as a student you will always need to read in an active way. Active reading involves reading with a purpose; that is reading in order to grasp definitions and meanings, understand debates, and identify and interpret evidence. It requires you to engage in reading and thinking at one and the same time in order to:

identify key ideas

extract the information you want from the text

process that information so that it makes sense to you

re-present that information in assessments, using your own words.

It may involve you pausing at intervals to think about what you have just read, checking that you have grasped the main point and perhaps even noting down questions that come to mind or highlighting key words that you might want to return to at a later date. A crucial part of active reading is matching the way you read to the purpose you have in mind – that is reading for a purpose.

2 Purposeful reading

2.1 Reading techniques: scanning

There are three main techniques that you can use in order to read in such a way as to achieve your purpose: scanning, skimming, and focused reading. Let's take each in turn.

The technique of scanning is a useful one to use if you want to get an overview of the text you are reading as a whole – its shape, the focus of each section, the topics or key issues that are dealt with, and so on. In order to scan a piece of text you might look for sub-headings or identify key words and phrases which give you clues about its focus. Another useful method is to read the first sentence or two of each paragraph in order to get the general gist of the discussion and the way that it progresses.

Activity 2

Read the Scotsman article on the child curfew scheme in Hamilton again (reproduced below). Have a go at scanning the text for clues about the shape and general focus of the article. Jot down any key words or ideas that seem to jump out at you. You will find our feedback and comments noted in the "Now read the discussion" link beneath the article. Try not to read these until you have completed the activity.

Hamilton child safety curfew to be extended

Calls for scheme to go national, despite rise in crime on estates where trial held

Jim Wilson

The expansion of the so-called child curfew in Hamilton was announced yesterday as the Government called for the controversial scheme to be copied across Scotland.

The operation will now cover the whole of the Lanarkshire town, despite official research suggesting that crime rose in the three housing estates where it was launched a year ago.

The extension of the initiative, in which children out after dark are taken home, was announced as Strathclyde Police and the Scottish Office released analysis suggesting the community patrols have overwhelming support in the town.

Opinion polls in Hamilton, including one run by a local newspaper, revealed more than 90 per cent backing for the curfew, although more than half of all children thought police did not understand youngsters and stopped them for no reason.

Yesterday, the Scottish Office urged the other seven Scottish forces to copy the curfew, despite critics claiming the operation is unnecessary and heavy-handed.

No other Scottish force has voiced any interest in adopting a similar strategy but Henry McLeish, the Scottish Office home affairs minister, said every town and city could benefit. He said chief constables must decide their own operational strategies, but the success of the initiative in Hamilton could not be questioned and promised to send the new analysis to every force and police board.

‘I would be delighted to see this initiative copied and developed elsewhere,’ he said.

‘This should be the start of a huge debate about how best to reclaim our communities for decent, ordinary people.’

Research, commissioned by the Government and carried out by Stirling University, looked at the first six months of the operation, October 1997 to April 1998, and revealed that reported crime in the chosen estates fell by 23 per cent compared with the previous six months.

However, researchers concede seasonal trends meant more crimes are committed in summer and, when compared with the same six months of the year before, reported crime actually rose on the estates of White-hill, Hillhouse, and Fairhill, by 17 per cent.

In addition, a survey in Hillhouse revealed that, while 44 per cent of people felt safer since the curfew was launched, a rising number of residents, 84 per cent, would not now enter certain areas of the estate.

Critics claim police should already be protecting very young children and Save the Children in Scotland fears the rights of young people could be violated. Yesterday, the charity's director, Alison Davies, said the research demanded careful scrutiny. ‘The figures and factors underpinning the research must be studied closely’.

The Government is keen for the Hamilton scheme to be a template for adoption by forces across Britain, but John Orr, the Strathclyde chief constable, conceded the research was not wholly supportive.

He stressed, however, that complaints to the police had fallen by 20 per cent in the pilot areas while the initiative, which will be continued as a pilot project for another year, had won backing from parents, children, and traders.

He said the scheme had been misrepresented as a curfew intended to reduce crime, but had instead been driven by the need to protect vulnerable children and encourage their parents to take more responsibility.

He said: ‘The suggestion that officers are going around like dog-catchers snatching children off the streets is simply wrong. There has not been a single complaint about the initiative and it has clearly been given the community's seal of approval.’

Mr Orr said the number of community officers involved in the expanded initiative would have to be doubled, possibly trebled, from the two teams of six currently involved.

A total of 280 children have been returned home over the past year. Five were charged with offences. Seventy per cent were boys, 14 per cent were aged under eight years old, and almost ten per cent were drunk. Sixty-one children have been taken home in the last six months compared with 221 in the first half of the trial, and officers believe the reduction indicates that more parents are taking responsibility for their children.

Allan Miller, the director of the Scottish Centre for Human Rights, said there was legitimate scepticism concerning crime figures and claimed the research proved only that treating all youngsters as potential criminals is not the answer. He said ‘The statistics on crime complaints and safety perceptions are mixed if looked at on the whole. For the police, the lesson should be to listen to and understand young people and to recognise their needs and rights.’

Mr Miller said 77 per cent of the children taken home by police were aged 12 to 15 and had done nothing wrong. He said it was significant the scheme had been renamed since being launched to include the protection of youngsters.

Meanwhile, South Lanarkshire Council yesterday announced the opening of a new £3 million centre for young people as part of the increased provision of youth facilities.

Discussion

With just a brief scan of the text we came up with the following:

Plans to expand the scheme

Crime rise/effectiveness of scheme?

Much support for scheme

No interest from other forces

Research findings

Feeling safer

Complaints/support

Community officer numbers

Numbers of children involved

Human rights issues

New centre for young people planned

Comparing your notes with ours, you will probably find that we have some points in common, but perhaps you also got some different ideas down as well. That's to be expected. The point of the activity is not to come up with exactly the same information but rather to demonstrate the usefulness of scanning as a technique for getting a general sense of the article.

Clearly, this method of reading does not generate much in the way of detail and perhaps you are wanting to extract more information on a particular issue or aspect of the debate. Skimming is a reading technique which enables you to identify specific information in a text as opposed to getting a more general idea.

2.2 Reading techniques: skimming

You might want to find information about the effectiveness of the child curfew scheme in Hamilton but be less interested in some of the other issues that are raised in The Scotsman piece. One way of extracting this kind of specific information is to skim the article for key words – such as ‘research’ – and statistics which may give you evidence of the effectiveness or otherwise of the scheme. This method is also especially useful when you are searching for something particular that you have previously read but cannot remember exactly where it is located.

Activity 3

Have a go at skimming The Scotsman article for key words such as ‘research’ and any statistical evidence that may be presented. You will find our feedback and comments noted in the "Now read the discussion" link beneath the article. Try not to read these until you have completed the activity.

Hamilton child safety curfew to be extended

Calls for scheme to go national, despite rise in crime on estates where trial held

Jim Wilson

The expansion of the so-called child curfew in Hamilton was announced yesterday as the Government called for the controversial scheme to be copied across Scotland.

The operation will now cover the whole of the Lanarkshire town, despite official research suggesting that crime rose in the three housing estates where it was launched a year ago.

The extension of the initiative, in which children out after dark are taken home, was announced as Strathclyde Police and the Scottish Office released analysis suggesting the community patrols have overwhelming support in the town.

Opinion polls in Hamilton, including one run by a local newspaper, revealed more than 90 per cent backing for the curfew, although more than half of all children thought police did not understand youngsters and stopped them for no reason.

Yesterday, the Scottish Office urged the other seven Scottish forces to copy the curfew, despite critics claiming the operation is unnecessary and heavy-handed.

No other Scottish force has voiced any interest in adopting a similar strategy but Henry McLeish, the Scottish Office home affairs minister, said every town and city could benefit. He said chief constables must decide their own operational strategies, but the success of the initiative in Hamilton could not be questioned and promised to send the new analysis to every force and police board.

‘I would be delighted to see this initiative copied and developed elsewhere,’ he said.

‘This should be the start of a huge debate about how best to reclaim our communities for decent, ordinary people.’

Research, commissioned by the Government and carried out by Stirling University, looked at the first six months of the operation, October 1997 to April 1998, and revealed that reported crime in the chosen estates fell by 23 per cent compared with the previous six months.

However, researchers concede seasonal trends meant more crimes are committed in summer and, when compared with the same six months of the year before, reported crime actually rose on the estates of White-hill, Hillhouse, and Fairhill, by 17 per cent.

In addition, a survey in Hillhouse revealed that, while 44 per cent of people felt safer since the curfew was launched, a rising number of residents, 84 per cent, would not now enter certain areas of the estate.

Critics claim police should already be protecting very young children and Save the Children in Scotland fears the rights of young people could be violated. Yesterday, the charity's director, Alison Davies, said the research demanded careful scrutiny. ‘The figures and factors underpinning the research must be studied closely’.

The Government is keen for the Hamilton scheme to be a template for adoption by forces across Britain, but John Orr, the Strathclyde chief constable, conceded the research was not wholly supportive.

He stressed, however, that complaints to the police had fallen by 20 per cent in the pilot areas while the initiative, which will be continued as a pilot project for another year, had won backing from parents, children, and traders.

He said the scheme had been misrepresented as a curfew intended to reduce crime, but had instead been driven by the need to protect vulnerable children and encourage their parents to take more responsibility.

He said: ‘The suggestion that officers are going around like dog-catchers snatching children off the streets is simply wrong. There has not been a single complaint about the initiative and it has clearly been given the community's seal of approval.’

Mr Orr said the number of community officers involved in the expanded initiative would have to be doubled, possibly trebled, from the two teams of six currently involved.

A total of 280 children have been returned home over the past year. Five were charged with offences. Seventy per cent were boys, 14 per cent were aged under eight years old, and almost ten per cent were drunk. Sixty-one children have been taken home in the last six months compared with 221 in the first half of the trial, and officers believe the reduction indicates that more parents are taking responsibility for their children.

Allan Miller, the director of the Scottish Centre for Human Rights, said there was legitimate scepticism concerning crime figures and claimed the research proved only that treating all youngsters as potential criminals is not the answer. He said ‘The statistics on crime complaints and safety perceptions are mixed if looked at on the whole. For the police, the lesson should be to listen to and understand young people and to recognise their needs and rights.’

Mr Miller said 77 per cent of the children taken home by police were aged 12 to 15 and had done nothing wrong. He said it was significant the scheme had been renamed since being launched to include the protection of youngsters.

Meanwhile, South Lanarkshire Council yesterday announced the opening of a new £3 million centre for young people as part of the increased provision of youth facilities.

Discussion

In skimming the article for this more specific information using the word ‘research’, we identified one or two particularly informative sections, each with a rather different focus:

The section on the Stirling University study (paragraphs 9–11)

The section on research which sought to illustrate the false thrust of the schemes approach (3rd paragraph from the end)

Skimming for figures or statistics generated a couple more relevant sections, though these had a different focus again:

The section on local public support (paragraph 4)

The section on police complaints (paragraph 14)

Again, you might have pinpointed different sections of the article, but the main thing is that you were able to use this technique in order to identify more specific information than had been possible using the scanning approach.

Both skimming and scanning generate different kinds of information and can thus be used when you have rather different purposes in mind. However, what they have in common is that they do help you to get an in-depth, more detailed understanding of the article as a whole. A third technique – focused reading – is more useful for this purpose. This is a slower method of reading as it takes the material bit by bit and allows time for active thinking, whereby you begin to process the information presented, and perhaps even jotting down a few notes or questions raised by the material. It enables you to follow the argument more closely and really get to grips with the key ideas and concepts as well as the evidence that is presented. Focused reading is therefore a more intensive approach than either skimming or scanning. As such, it is more fruitful to engage in short bursts of it, when your levels of concentration are high. Indeed, one useful method you might try involves combining the three techniques, perhaps scanning the text first and maybe even skimming for more detailed, focused information which you can mark for future use, before going on to re-read the piece in a more focused way later.

2.3 Reading techniques: focused reading

Activity 4

Have a go at reading The Scotsman article again, this time in a more focused way. Think about each section of the text, breaking off at regular intervals in order to identify and extract the main points or examples, and jot down some notes and questions that come to mind as you read. You will find our feedback and comments noted in the "Now read the discussion" link beneath the article. Try not to read these until you have completed the activity.

Hamilton child safety curfew to be extended

Calls for scheme to go national, despite rise in crime on estates where trial held

Jim Wilson

The expansion of the so-called child curfew in Hamilton was announced yesterday as the Government called for the controversial scheme to be copied across Scotland.

The operation will now cover the whole of the Lanarkshire town, despite official research suggesting that crime rose in the three housing estates where it was launched a year ago.

The extension of the initiative, in which children out after dark are taken home, was announced as Strathclyde Police and the Scottish Office released analysis suggesting the community patrols have overwhelming support in the town.

Opinion polls in Hamilton, including one run by a local newspaper, revealed more than 90 per cent backing for the curfew, although more than half of all children thought police did not understand youngsters and stopped them for no reason.

Yesterday, the Scottish Office urged the other seven Scottish forces to copy the curfew, despite critics claiming the operation is unnecessary and heavy-handed.

No other Scottish force has voiced any interest in adopting a similar strategy but Henry McLeish, the Scottish Office home affairs minister, said every town and city could benefit. He said chief constables must decide their own operational strategies, but the success of the initiative in Hamilton could not be questioned and promised to send the new analysis to every force and police board.

‘I would be delighted to see this initiative copied and developed elsewhere,’ he said.

‘This should be the start of a huge debate about how best to reclaim our communities for decent, ordinary people.’

Research, commissioned by the Government and carried out by Stirling University, looked at the first six months of the operation, October 1997 to April 1998, and revealed that reported crime in the chosen estates fell by 23 per cent compared with the previous six months.

However, researchers concede seasonal trends meant more crimes are committed in summer and, when compared with the same six months of the year before, reported crime actually rose on the estates of White-hill, Hillhouse, and Fairhill, by 17 per cent.

In addition, a survey in Hillhouse revealed that, while 44 per cent of people felt safer since the curfew was launched, a rising number of residents, 84 per cent, would not now enter certain areas of the estate.

Critics claim police should already be protecting very young children and Save the Children in Scotland fears the rights of young people could be violated. Yesterday, the charity's director, Alison Davies, said the research demanded careful scrutiny. ‘The figures and factors underpinning the research must be studied closely’.

The Government is keen for the Hamilton scheme to be a template for adoption by forces across Britain, but John Orr, the Strathclyde chief constable, conceded the research was not wholly supportive.

He stressed, however, that complaints to the police had fallen by 20 per cent in the pilot areas while the initiative, which will be continued as a pilot project for another year, had won backing from parents, children, and traders.

He said the scheme had been misrepresented as a curfew intended to reduce crime, but had instead been driven by the need to protect vulnerable children and encourage their parents to take more responsibility.

He said: ‘The suggestion that officers are going around like dog-catchers snatching children off the streets is simply wrong. There has not been a single complaint about the initiative and it has clearly been given the community's seal of approval.’

Mr Orr said the number of community officers involved in the expanded initiative would have to be doubled, possibly trebled, from the two teams of six currently involved.

A total of 280 children have been returned home over the past year. Five were charged with offences. Seventy per cent were boys, 14 per cent were aged under eight years old, and almost ten per cent were drunk. Sixty-one children have been taken home in the last six months compared with 221 in the first half of the trial, and officers believe the reduction indicates that more parents are taking responsibility for their children.

Allan Miller, the director of the Scottish Centre for Human Rights, said there was legitimate scepticism concerning crime figures and claimed the research proved only that treating all youngsters as potential criminals is not the answer. He said ‘The statistics on crime complaints and safety perceptions are mixed if looked at on the whole. For the police, the lesson should be to listen to and understand young people and to recognise their needs and rights.’

Mr Miller said 77 per cent of the children taken home by police were aged 12 to 15 and had done nothing wrong. He said it was significant the scheme had been renamed since being launched to include the protection of youngsters.

Meanwhile, South Lanarkshire Council yesterday announced the opening of a new £3 million centre for young people as part of the increased provision of youth facilities.

Discussion

Our attempt generated the following notes:

Hamilton child curfew police to be extended across Scotland, despite evidence of increased crime in launch areas.

Support in town for curfew triggered expansion: 90% local backing.

Critics claim it is a heavy-handed approach.

No other force has expressed interest, yet S.O. say every town could benefit so scheme will be publicized.

Stirling University research focused on first 6 months (Oct. 1997-April 1998):

reported crime fell by 23%,

but seasonal trends may account for this – compared with same period in previous year reported crime actually rose by 17%,

44% of locals felt safer,

but 84% would not enter certain areas – a rise.

Critics, eg Save the Children in Scotland, argue the scheme is a violation of young people's rights and question its success.

Government support for scheme.

Strathclyde chief constable recognized research questioned effectiveness, but claimed 20% fall in police complaints and high levels of local support. Also claimed bad press for scheme – driven by concern for young people's safety and parental responsibility, not reducing crime.

Numbers of community officers involved set to rise.

280 children returned home in past year, 5 charged; 70% boys; 14 % under 8 years; almost 10% drunk.

Reduction in numbers returned in second 6 months compared with first claimed as evidence of success re. increased parental responsibility.

Scottish Centre for Human Rights: critical of approach which sees children as potential criminals where 77% (aged 12–15) returned home had done nothing wrong. Calls for a listening, need focused approach to young people (renaming of the scheme not enough).

Council to open centre for young people to increase Youth facilities in area.

But, in addition, pausing to think about the material generated a number of questions including:

Would the scheme have the same results in a different area?

How was public opinion measured? Was everyone included in the survey?

What bad press has there been about the scheme? Does it matter if the results of the Stirling research show that the scheme is not effective?

Might the reduction of numbers returned home in the second period of the scheme be a result of something other than increased parental responsibility? For example, changes to the implementation of the scheme?

Again, you probably got some similar points and questions to us, missed others but included additional ones of your own. What is important is not that our notes are identical, but that (a) you used the technique of focused reading in order to successfully extract the main points of the article in a way that makes sense to you, and (b) actively engaged with the material in such a way as to generate questions and ideas, as opposed to passively reading it only to forget much of it at a later date.

One thing you might notice about both your notes and ours is that they are not very usefully organized. For example, we have noted down a number of criticisms levelled at the scheme but they are not grouped together in such a way as to enable us to compare and contrast them, or draw out any common issues that may recur. This overlap or repetition of key ideas, albeit in rather different forms and illustrated by different examples, makes our notes longer than they might be. Later, in Section 7, we will look at a number of ways we might create more helpful notes which group points together around key ideas, themes or concepts – very useful when it comes to planning and writing assignments. However, first it is useful to highlight some of the problems that you might come across, particularly when reading more complex materials.

3 Strange words, long sentences and lost meanings

In reading for a purpose it is not unusual to get stuck on unfamiliar words and concepts or struggle with complex ideas and sentences. This section suggests tactics for coping with unfamiliar words (and inadequate dictionaries), unpacking complex sentences and retrieving lost meanings. In order to do this we will draw on an extract taken from a book, Crime and Society in Britain, by Hazel Croall (1998) which is a social science text. It thus contains more ‘conceptual’ or ‘technical’ terminology than was evident in The Scotsman article.

Activity 5(a)

Read the extract reproduced below and highlight any unfamiliar words or difficult sentences that you come across. After you have done that, click the "Now read the discussion" link beneath the article to read our feedback and notes.

Click below to open the extract by Hazel Croall, Crime and society in Britain.

Discussion

We thought that the word ‘indictable’ may present a problem and we wondered what the difference between an ‘indictable’ and a ‘summary’ offence was. Later in the extract the concept of ‘natural selection’ is introduced, a rather specialist term which is not necessarily part of our everyday language. Similarly, towards the end of the piece, terms such as ‘the anomie paradigm’ and ‘subcultural theory’ are used – both likely to be unfamiliar to most people.

Thinking about how you might deal with these difficult words and concepts there are a number of strategies you might try:

Dictionaries can be helpful where the word is simply unfamiliar to you but is in everyday use. However, if the word represents a particular social scientific concept or idea, general dictionaries are less useful. For example, if you did wonder what the word ‘indictable’ meant, looking it up in The Concise Oxford Dictionary (7th edition) would have yielded the following: ‘rendering one liable’ – not particularly helpful.

A social science dictionary can be useful but may not necessarily provide the answer you are looking for. Meanings are contested in the social sciences – different words mean different things to different people, including authors of social scientific dictionaries! So the meaning ascribed to a word in even a specialist dictionary might not be the same meaning that the author of the textbook you are reading had in mind.

So what other methods might you use?

An alternative approach is to look for clues in the part of the text where the word appears. For example, in the paragraph where the term ‘natural selection’ appears there are also references made to the concept of evolution and the process whereby characteristics are ‘bred out’ of certain individuals, both of which imply something to do with genetics. So, from looking at the context in which the word appears, you are already building up enough of a general picture to enable you to move on.

Had there been no immediate clues you might usefully have looked ahead – marked the problematic term or concept and read on to see if it was revisited with more explanation later. For example, in the second paragraph on page 16 ‘summary offences’ are referred to as ‘generally assumed to be less serious’. In this way a working understanding of ‘indictable’ and ‘summary’ offences can be developed whereby indictable offences are constructed as more serious than summary offences. It might not be very sophisticated or complex but again it enables you to move forward. Similarly, subcultural theory may not be something with which you are familiar, but if you read the whole of the relevant paragraph you are given some useful hints about what it is concerned with – such as ‘lad’ culture and ‘fan’ culture. These are examples of subcultures and thus help you to pinpoint the general focus of such a theory which may be enough to be going on with. Retracing the argument to see if it points in a particular direction is also a potentially useful method to draw upon.

If none of the above strategies prove helpful, you might simply ask yourself to what extent it matters. For example, is it crucial to the article as a whole or for the purpose you have in mind to understand what the ‘anomie paradigm’ is? If not, skip it. If it is, there are other sources, in the library for example, that you might draw upon, not least the book from where the extract was taken.

Turning our attention to difficult sentences, we felt that ‘Lombroso and Ferrero, to whom criminal men were biologically less evolved, saw women as being less evolved than men and closer to primitive types and argued that natural selection had bred out their criminal tendencies’ (third paragraph on page 16 of the reading) was rather complex and a possible stumbling block.

One approach to dealing with sentences such as this, which try to say a lot in a small number of words, is to divide it up and create several simpler sentences or statements. Trying this technique we came up with the following:

Lombroso and Ferrero believed that:

Criminal men were biologically less evolved than non-criminal men

Women were less evolved than men

Women were thus closer to primitive types

Women's criminal tendencies had been bred out of them through natural selection

Dividing complex sentences up into less complex ones enables you to get a clearer sense of the ideas being presented and separate out different ideas so that you can use them more easily. Of course, sometimes this may not help. Another potentially useful technique involves focusing on those sentences which come immediately before or after the complex one – they may give you additional clues. The key is to take it slowly and be active about solving the problem, as opposed to letting such difficulties immobilize or panic you.

Activity 5(b)

Have a go at using these methods to tackle other strange and unfamiliar words and complex sentences that you noted in the extract above.

You may have a range of different responses so we haven't provided a specific comment which might be seen as a ‘right answer’.

The first half of this course has focused on reading. However, throughout we have made reference to jotting down ideas and questions, marking difficult words and concepts. In doing so we have begun to illustrate how active reading in particular is inherently linked to and bound up with writing. In the second half of the course we are going to explore in more detail the relationship between the skills of purposeful reading and those of note taking.

4 Taking the point: identifying key ideas

As earlier activities have demonstrated, active reading and note taking often come hand-in-hand. In order to read effectively we often have to jot down the main ideas and key words introduced in the text. We might also note down one or two questions as we go along to assist in the ‘thinking’ part of the process. But, like reading, note taking comes in all shapes and sizes, and different kinds of notes can be useful for different purposes. Moreover, good note taking, like purposeful, active reading, involves a series of processes from highlighting key ideas in the text to constructing more complex diagrammatic representations of the main points.

By reading in an active way you have already begun to identify key ideas presented in a text and perhaps even jot them down. However, an alternative method of identifying key ideas is to use a highlighting technique. This involves actually marking important parts of the text by underlining or using a highlighter pen and thus creating a more permanent reminder of key ideas. This approach is designed to promote selectivity and encourages you to focus on the core meanings of an extract. However, before you have a go, you should take note of the following warnings:

Highlighting involves you making judgements about what is important. It is not about capturing every detail but, rather like scanning, is about getting a general overview of the big ideas. Do not be tempted to highlight everything or nearly everything – this renders the exercise pointless as you will be no better off with everything underlined than you were with nothing underlined.

A good rule of thumb is to underline or highlight one sentence per paragraph. Paragraphs usually focus on one key point, and while they might include an illustrative example which may be useful, it is the main point that you need to identify first and foremost. Some people find it more useful, then, to add in a short note of the example in the margin next to the highlighted sentence.

Do not see highlighting as the end of the process – an alternative to full note taking. It is merely the first step. Highlighting does not organize points into any order that makes sense to you. Nor can you use highlighted sections to reorganize ideas around themes or in answer to assignment questions.

Activity 6

Read through the extract from Hazel Croall's book again, this time identifying and highlighting the key ideas. This will be easier now that you have already read through the text once before. In fact, the best highlighting is often achieved on a second reading.

You will find our feedback and comments noted in the "Now read the discussion" link beneath the article. Try not to read these until you have completed the activity.

Click below to open the extract by Hazel Croall, Crime and society in Britain.

Discussion

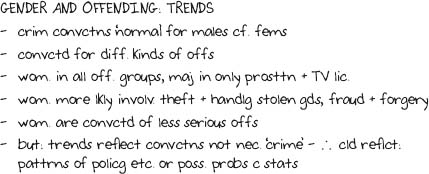

We highlighted the following parts of the text:

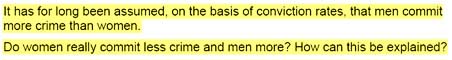

We highlighted these introductory sentences as they seemed to capture the key focus of the extract – different conviction rates for men and women, what they might mean and how they might be explained.

We thought it was important to highlight that the trends discussed in the article were based on conviction rates as opposed to any other measure -these six words will be enough to remind us of that so we did not feel it was necessary to mark the whole sentence.

We felt that these sentences were important as they summarized the main trends for men and women, based on conviction rates. We didn't highlight the statistics presented or details about particular offences committed. This is because the technique of highlighting is a way of identifying key ideas. We can go back to the text and extract more detailed information, perhaps using a skimming technique, at a later date if we find that we need to. Alternatively, if we decide to take more detailed notes about the whole of the extract, say in preparation for an assignment, this material would be included there.

This sentence seemed important to us as it suggests that the trends may say more about the conviction process, for example, than actual crime rates.

The first of these sentences summarizes one particular approach to explaining women's apparent lack of criminality, whereas the second gives useful examples of the kinds of factors seen as important to those writing from this perspective.

Early versions of sex role theory however, based on functionalist approaches, rarely questioned the ‘naturalness’ of these role distinctions or the gender relationships which they reflected. They too, therefore, saw criminal women as ‘abnormal’

Similarly, these sentences all summarize a number of alternative approaches whilst signalling possible weaknesses with them. You might have noticed that we have also highlighted sub-headings as we have gone along. This is because the author introduces different issues as well as different explanatory approaches to the same phenomenon – in this case crime. To signal where these are placed in the text can be helpful for when we return to the article at a later date and/or for when we want to generate a set of handwritten notes about the piece. Indeed, it is to this issue of making short notes that we can now turn.

5 Keeping it short: jottings, abbreviations and symbols

Once you have identified the key ideas you are in a position to take some brief notes or jottings. Indeed, you will find that highlighting on its own is a rather passive process and as a result you may not remember the ideas that you identified. Rather than returning to the highlighted text every time you want to revisit or draw upon these ideas, only to find that what you have marked does not make sense to you anymore, it is useful to develop a form of short note taking. So, getting key ideas down in shorthand form is useful both when highlighting is not enough and when you want to get working with the material more actively. Of course, some people find it useful to add short notes into the margins of highlighted texts to remind themselves of why they felt a point to be relevant or of an example they could use to illustrate a particular issue. This involves more active engagement with the text, but it is not until you start to make your own notes, in your own words (of which more in Section 8.1) that you can really check that you understand ideas enough to work with and use them, particularly in preparation for assignments and exams.

As with highlighting, you need to take care when taking short notes to be selective. Trying to get everything down is very time consuming and results in notes that are as long as the article itself! One way of both cutting down the time spent making notes and keeping them to an appropriate length is to make use of symbols, shorthand and abbreviations. You might already know some, to which you can add others that you make up throughout your time as a student. We use a whole range of symbols and abbreviations some of which are reproduced below:

In addition, we use our own form of shorthand which sometimes entails leaving out vowels or cutting off the end of words. This method is particularly effective where longer words are concerned. For example, concentrated becomes cone, advantage and disadvantage become adv. and disadv. respectively, and consequently becomes consq. Developing your own version which makes sense to you can be extremely time efficient and after a while it becomes a language of your own which flows from the pen easily.

Activity 7

Return to the Croall extract on gender and crime (Reading I) and have a go at making brief notes using any abbreviations or forms of shorthand that you know. You might want to take this opportunity to create and try out some new ones too.

You will find our feedback and comments noted in the "Now read the discussion" link beneath the article. Try not to read these until you have completed the activity.

Click below to open the extract by Hazel Croall, Crime and society in Britain.

Discussion

Given the individualistic nature of most shorthand there is perhaps little to be gained from us sharing our notes with you at this stage. However, you might want to take a moment to look back over the notes that you have produced and ask yourself: are they short and to the point?, can they be edited down in any way?, what might I need to add to make them even more helpful? If you do need to be even more succinct, have another go now. Similarly, if you can think of things you might usefully add – an illustrative example, or page references – to help you find key points again, add them in now.

6 Extracting a summary

In developing short notes you are already beginning to extract key ideas from the text. To assist you further in this you might also find it helpful to bring the points you have highlighted and/or made short notes about together. This involves the use of link sentences and words, perhaps even the addition of short quotes taken from the text directly, and examples or additional words of explanation. In this way your notes build up into a summary which you can use more easily.

Activity 8

Have a go yourself using the short notes that you made from the Croall extract.You will find our feedback and comments noted in the "Now read the discussion" link. Try not to read these until you have completed the activity.

Discussion

Our short notes for the first part of the extract are reproduced below and any additional information, for example link sentences and words as well as quoted material that we added to make a summary, are underlined. Below each set of points we have included a translation of our notes so that you can understand them.

Translation:

assumed men commit more crime than women: based on conviction rates

do they? how is this explained?

Translation:

criminal convictions are more normal for males than females

men and women are convicted of different types of offences

women in all offence groups but represent the majority only regarding prostitution and TV licence non-payment

women are more likely to be involved in theft/handling stolen goods/ fraud/forgery

women are convicted for less serious offences

but: trends reflect conviction rates as opposed to crime rates – therefore they could reflect patterns of policing or problems with statistical data

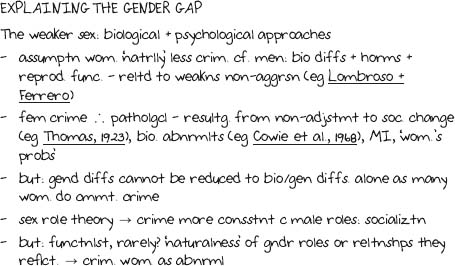

Translation:

assumes women are naturally less criminal than men as a result of biological differences, hormones and reproductive function being related to non-aggression

female crime is therefore seen as pathological – resulting from a non- adjustment to social change, biological abnormalities, mental illness and ‘women's problems’

but: gender differences cannot be reduced to biological/genetic differences alone as many women do commit crime

sex role theory claims that crime is more consistent with male roles: role of socialization

but this is functionalist: it rarely questions the naturalness of gender roles or the relationships they reflect, thus giving rise to claims that criminal women are abnormal

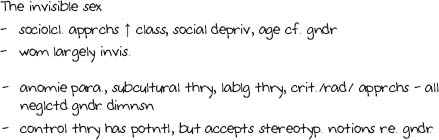

Translation:

sociological approaches increase the focus on class, social deprivation and age

women remain largely invisible

the anomie paradigm, subcultural theory, labelling theory, and critical/ radical approaches all neglected the gender dimension

control theory has potential but accepts stereotypical notions regarding gender

As you can see we made a note of the bibliographical details of the extract (from the list of references on page 20) at the top of our notes. This is crucial if you want to use notes at a later stage, perhaps for writing assignments, as it enables you to acknowledge the source of these ideas and arguments (see Section 8 - page 15 of this course - for more on referencing, acknowledging sources and avoiding plagiarism). We also thought it might be useful to note down some of the proponents of particular perspectives. This means that if we need to write about these ideas we can attach them to relevant ‘owners’. This in turn enables us to (a) stand back from different viewpoints and subject them to critical scrutiny, and (b) present a whole range of different and competing ideas and viewpoints without appearing to contradict ourselves. We can simply represent these views as different takes on the same issue. No quotes ‘jumped out’ at us, so we did not include any this time, but we did use our highlighted subheadings which proved to be a useful way of organizing our notes.

So far we have looked at how to highlight key ideas in the text itself and how to use the highlighted bits to create short notes and summaries. Identifying and extracting important points will take you a long way, but this is not yet really active reading. You are making judgements about what is important to select, but you are not yet actively working on what you have read. The next stage, then, is to begin to take the ideas into your thoughts, make your own sense of them, and begin to ‘talk to’ what you are reading: check you understand the main points; see how they relate to your own experience; think up other examples that may illustrate them; see how they stand up to questioning; and sometimes query them or begin to put forward criticisms. This is about reading and thinking.

7 Reading and thinking

7.1 Processing meanings

Reading and thinking requires you to begin to process the material you read in preparation for re-presenting it in assessments. Initially, processing happens in your head. Selecting what to identify and extract will start the process off. Summarizing the arguments continues this process and, crucially, gets you started on reproducing ideas in your own words. The next stage is to develop your notes further by thinking more consciously about the material you have read and the points you have noted down. Indeed, you should be getting the essential point now that reading and thinking merge into one activity. We have already explored some of the possibilities for introducing questions as you read and supplementing highlighted material and short notes with additional words and quotes. Here we will look at two additional issues: how to reorganize notes into a more usable and fuller form, and how to internalize and interrogate them.

7.2 Reorganizing notes

The technique of re-reading completed notes and supplementing them with comments and queries is a useful way of processing ideas. Another way of processing ideas is to reorganize notes around a set of questions or thematic headings. This is particularly useful for those notes that you will be drawing upon for planning and writing assignments. They can be reworked and key concepts and ideas can thus be applied to different types of questions and issues.

Activity 9(a)

Read the extract by Lucia Zedner taken from The Oxford Handbook of Criminology reproduced below. Use the skills that we have worked on in the earlier sections of this booklet to generate a summary of key ideas. Then organize those ideas by grouping them together around a number of themes or sub-headings. Afterwards, click the "Now read the discussion" link beneath the article to read our feedback and comments.

Click below to open the extract by Lucia Zedner, Victims.

Discussion

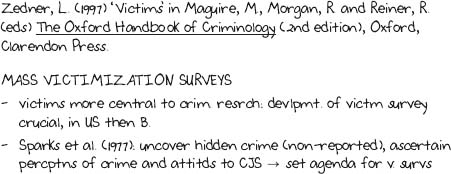

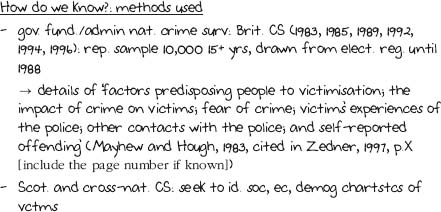

As with the last extract, we noted down the bibliographical details of the Zedner text at the top of the page. We then noted down a few questions that we not only tried to keep in mind when we were reading the extract but also used to help us organize our notes: What trends have victim surveys uncovered? Who are the victims? Are some groups of people more at risk of becoming victims of particular types of crime than others? How do we know? What methods are used in victim studies? What are the strengths and weaknesses of victim studies? Again, you might have started rather differently, choosing different headings or themes and focusing on different questions.

That's fine – the point here is to use a framework that is useful and makes sense to you.

Translation:

victims are now more central to criminological research: the development of the victim survey, first in the USA and then in Britain, has been crucial

Sparks and others (1977) uncovered hidden or non-reported crime and ascertained people's perceptions of crime and the Criminal Justice System, thus setting the agenda for various surveys

Translation:

the government funds and administers the national crime survey. British crime surveys have been carried out in 1983, 1985, 1989, 1992, 1994 and 1996, drawing on a representative sample of 10,000 people over the age of 15, drawn from the electoral register until 1988. The British Crime Survey gives details of ‘factors predisposing people to victimisation; the impact of crime on victims; fear of crime; victims’ experiences of the police; other contacts with the police; and self-reported offending’ (Mayhew and Hough, 1983, cited in Zedner, 1997 [include the page number if known])

there are also Scottish and cross-national crime surveys which seek to identify the social, economic and demographic characteristics of victims

Translation:

reported crime is only a small fraction of actual crime: for example, one-quarter of property crime is reported and only one-fifth of violent offences

show trends over time: for example, increases in property crime and the reporting of crime

risk of being affected by crime: high risk of minor crime; low risk of major crime

commonality of offences: the incidence of theft (especially car) is greater than common assaults, which is greater than burglary, which, in turn, is greater than wounding and robbery

Translation:

the risk of personal and property crime is related to geography, age, sex, routine (for example, alcohol consumption/going out), ‘race’/ethnicity

Translation:

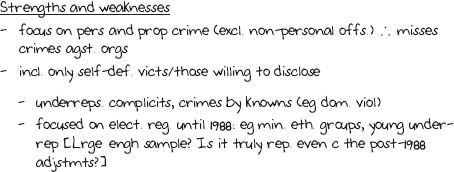

focus on personal and property crime (excludes non-personal offences) and therefore misses crimes against organizations

includes only self-defined victims/those willing to disclose

under represents crime where the victim is complicit and crimes by those known to the victim (e.g. in cases of domestic violence)

focused on electoral register until 1988: e.g. minority ethnic groups, young people are under-represented [Is the sample large enough? Is it truly representative even with the post-1988 adjustments?]

Organizing notes around a number of questions (or themes) ensures that they are in a usable format from the outset. This saves time and also gets you processing the materials in an active way. Again, you should notice that we didn't always include detailed examples (we can go back to the highlighted bits of the text at a later date if required), though this time we did find one or two quotes which may usefully illustrate key points should we introduce them into an assignment, for example.

Activity 9(b)

Try the note-taking exercise again but this time use the extract by David Smith reproduced below and try to organize your notes in a different way – that is, by constructing a spider diagram. This involves putting the main subject of the extract in the spider's body at the centre of the page and adding spider's legs around it, each with a different key point attached.

Spider diagrams are sometimes referred to as a concept or mind maps. You will find that the concept mapping software compendium has been included in the LabSpace area of this website. When you are confident of your spider diagram’s content, you could experiment with using Compendium to map out your thoughts. You might also like to share your compendium map with others by uploading it to LabSpace.

You will find our feedback and comments noted in the "Now read the discussion" link beneath the article. Try not to read these until you have completed the activity.

Reading 3

David Smith: ‘Racially motivated crime and harassment’

We have seen the elevated rate of victimization among ethnic minorities arises, to some extent, because these minorities fall into demographic groups that are at higher than average risk, and because they tend to live in areas where victimization risks are relatively high. However, another reason is that ethnic minorities are the objects of some racially motivated crimes. They may also be the victims of a pattern of repeated incidents motivated by racial hostility, where many of these events on their own do not constitute crimes, although some crimes may occur in the sequence, so that the cumulative effect is alarming and imposes severe constraints on a person's freedom and ability to live a full life. Racial harassment is the term that is used to describe a pattern of repeated incidents of this kind.

Genn (1988) and Bowling (1993) have pointed out that victim surveys have not been designed to describe patterns which develop overtime. Instead, they have aimed to count discrete incidents, using definitions parallel to those applied by the courts. This is most appropriate for crimes such as car theft or burglary, where most incidents are discrete from the viewpoint of the victim. It is least appropriate for crimes which take place within a continuing relationship (family violence, incest) or within a restricted social setting (the school, the workplace, the street).

A further difficulty in studying racially motivated crime or racial harassment is establishing racial motivation. One approach is to accept the victim's view; another is for an observer to make a judgement based on a description of the facts. Definitions used vary in the emphasis given to these two types of criterion, and in other detailed ways, so that it is often difficult to compare the results from different studies.

Although racial attacks and harassment, on any reasonable definition, are ancient phenomena, they have ‘arrived relatively late on the political policy agenda and thence onto the agenda of various statutory agencies’ (FitzGerald, 1989). The first major report on the subject, Blood on the Streets, was published by Bethnal Green and Stepney Trades Council in 1978. Since then there has been an official report by the Home Office (1981) based on statistics of incidents recorded by the police; a report by the House of Commons Home Affairs Committee (1986), which has also recently initiated a further inquiry; and two reports by an Inter-Departmental Group set up to consider racial attacks (Home Office, 1989c, 1991). National statistics on racial incidents recorded by the police have been regularly reported in Hansard. National survey-based statistics were first generated by the third PSI [Policy Studies Institute (police commissioned)] survey of racial minorities carried out in 1982 (Brown, 1984). More comprehensive information has become available recently from the British Crime Surveys of 1988 and 1992 (Mayhew, Elliott, and Dowds, 1989; FitzGerald and Hale, 1996) and from the fourth PSI survey of ethnic minorities carried out in 1994 (Virdee, 1997).

Police records are virtually useless as a measure of the amount of racially motivated crime, because most of these incidents are not reported to the police, and because incidents that the victim regards as racially motivated are often not recorded as such by the police (Virdee, 1997: 262). In an analysis of the PSI 1982 survey of ethnic minorities, Brown (1984: 260, table 134) identified assaults where there was a probable racial motive from studying victims’ detailed descriptions of the incidents. On the most restrictive definition (counting assaults only where the motive was plainly racist) the survey showed an incidence of racial attacks around ten times higher than revealed by the statistics derived from police records and published by the Home Office (1981). Police statistics have shown large rises in racially motivated crime since the mid-1980s, but, as Virdee (1997) has pointed out, this could reflect an increase in rates of reporting or recording, and does not reliably demonstrate an actual increase in the level of harassment.

In the BCS [British Crime Survey] (1988 and 1992 combined), 24 per cent of offences reported by South Asians and 14 per cent of those reported by Afro-Caribbeans were racially motivated in the respondent's view. Types of incident most often seen as racially motivated were assaults and threats, and also household vandalism in the case of South Asians. These surveys showed only a slight increase between 1987 and 1991, in marked contrast with the police statistics, which showed a large increase (FitzGerald and Hale, 1996: table 2.3a).

PSI's 1994 survey asked about three types of incident (attacks, damage to property, and insults) in the past twelve months where the victim thought there was a racist motivation. Looking at the results for ethnic minorities combined (Caribbeans, South Asians, and Chinese) it found that 1per cent had been racially attacked, 2 per cent had been victims of racially motivated damage to property, and 12 per cent had been racially insulted. These results suggest that over a quarter of a million people had been subject to some form of racial harassment over a twelve-month period, as compared with the 10,000 incidents recorded by the police. There were some fairly small differences in experience of racial insults between specific minority groups, but no significant differences in the case of racial attacks and damage to property. Men, and people aged 16–44, were more likely to be victims of racial harassment than women, and those aged 45 or more. Racial harassment was a considerably greater hazard for ethnic minorities living in a predominantly white neighbourhood than for those living in a neighbourhood with a substantial ethnic minority population. This suggests that black or Asian neighbourhoods have protective value for the ethnic minorities living in them (Virdee, 1997).

The PSI findings confirm other sources in showing that racial harassment tends to be a process involving a sequence of incidents, rather than an isolated event. In fact, three-fifths of those subject to racial harassment in the past twelve months had experienced more than one incident, and 22 per cent had experienced five or more. In two-thirds of cases, there was more than one offender. Offenders were predominantly male and young, but one-third of them were thought to be aged 30 or over (Virdee, 1997).

Local surveys, like the PSI survey, have generally tried to cover low-level harassment as well as criminal offences. They tend to suggest that racial harassment, on a broad definition, is a problem affecting a high proportion of South Asians and Afro-Caribbeans (London Borough of Newham, 1986; Saulsbury and Bowling, 1991). In a study of an East London housing estate, Sampson and Phillips (1992) found over a period of six months an average of four and a half attacks against each of thirty Bengali families, although seven families were not attacked, while six families were attacked twelve or more times. A sequence of incidents recorded for one family was: stones thrown and chased; threatened and prevented from entering flat; punched and verbal abuse; attempted robbery; chased by gang of youths; common assault.

Taken together, these findings suggest that there is a substantial risk of racial harassment for members of ethnic minority groups in England and Wales, although only about one in seven of Afro-Caribbean and South Asian people are conscious of having changed or restricted their pattern of life in response (Virdee, 1997: 285). Racially motivated crime also accounts for about one-fifth of crime victimization of ethnic minorities, and therefore helps to explain their elevated rate of victimization.

References

Bowling, B. (1993), ‘Racist Harassment and the Process of Victimization: Conceptual and Methodological Implications for the Local Crime Survey’, in J. Lowman and B.D. MacLean, eds., Racist Criminology: Crime and Policing in the 1990s. Vancouver: Collective Press.

Brown, C. (1984), Black and White Britain: The Third PSI Survey. London: Heinemann.

FitzGerald, M. (1989), ‘Legal Approaches to Racial Harassment in Council Housing: The Case for Reassessment’, New Community, 16, 1: 93–105.

— and Hale, C. (1996), Ethnic Minorities: Victimisation and Racial Harassment: Findings from the 1988 and 1992 British Crime Surveys. Home Office Research Study No. 154. London: Home Office.

Genn, H. (1988), ‘Multiple Victimization’, in M. Maguire and J. Porting, eds., Victims of Crime: A New Deal? Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Home Office (1981), Racial Attacks: Report of a Home Office Study. London: Home Office.

— (1989c), The Response to Racial Attacks and Harassment: Guidance for the Statutory Agencies: Report of the Inter-Departmental Racial Attacks Group. London: Home Office.

— (1991), The Response to Racial Attacks: Sustaining the Momentum: The Second Report of the Inter-Departmental Racial Attacks Group. London: Home Office.

House of Commons Home Affairs Committee (1986), Racial Attacks and Harassment. Session 1985–86, HC 409. London: HMSO.

London Borough of Newham (1987), Report of a Survey of Crime and Racial Harassment in Newham. London: London Borough of Newham.

Mayhew, P., Elliott, D., and Dowds, L (1989), The 1988 British Crime Survey. Home Office Research Study No. III. London: HMSO.

Sampson, A., and Phillips, C. (1992), Multiple Victimization: Racial Attacks on an East London Estate. Police Research Group, Crime Prevention Unit Series, Paper No. 36. London: HMSO.

Saulsbury, W., and Bowling, B. (1991), The Multi-Agency Approach in Practice: the North Plaistow Racial Harassment Project. Research and Planning Unit Paper No. 64. London: HMSO.

Virdee, S. (1997), ‘Racial Management’, in T. Modood et al., Ethnic Minorities in Britain: Diversity and Disadvantage. London: Policy Studies Institute.

Discussion

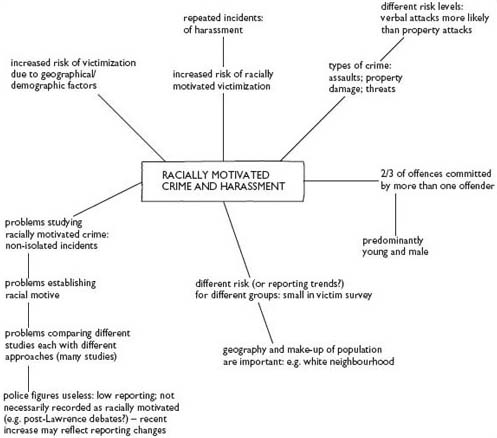

Our spider diagram is reproduced below. Once again we wrote the extract details on the top of the page. We also thought up some questions: What is the extent of racially motivated crime and harassment? Are all minority ethnic groups equally at risk? Do other social divisions, such as gender and age, have an impact?

Translation:

Some people find this alternative approach to note taking useful as diagrammatic representations can be more memorable – particularly useful then for revising themes and issues in preparation for exams. It is also easy to add on additional questions, ideas and examples at a later date. For example, you might want to make links to ideas presented elsewhere in your course materials, or something in the newspaper might provide you with a useful illustration. We felt that the debate around the Stephen Lawrence case and whether or not the police took racially motivated crimes seriously was relevant here, so we put a reminder to ourselves in brackets. Similarly, whilst the extract noted that different groups seemed to be more at risk than others of racially motivated crime, we thought the different percentages for South Asians and Afro-Caribbeans may be a reflection of different reporting patterns. So, again, we made an additional note to ourselves in brackets. It's a good idea, then, to get in the habit of revisiting your notes at intervals throughout your study to develop links, introduce new questions and examples, and thus continually reprocess key ideas.

7.3 Internalizing and interrogating key ideas

In addition to revisiting your notes at different times throughout the year, you might also look for opportunities to discuss key ideas with someone else - either a fellow student or someone outside of The Open University who is interested in contemporary social science debates. This can provide a helpful stimulus to internalizing them. Debating issues with someone else may well help you to generate further questions and critical observations, all part of processing and interrogating meanings. Moreover, being able to explain new ideas and concepts helps you to get ideas clear in your mind, and begins to develop your skills of representing them in your own words. It is to this crucial skill of writing in your own words that we can now turn.

8. Making the ideas your own

8.1 Re-presenting material

Wherever possible, you are encouraged to write in your own words, even when note taking. This is for a number of reasons: firstly, it gets you actively working with and processing key ideas; secondly, as noted above, it allows you to check that you have understood – if you can explain it to someone else using your own words and without relying on those of the authors you have cracked it; and thirdly, it enables you to demonstrate your understanding, especially to your tutor, in assessments. To rely on an author's words and not acknowledge it through referencing (see Section 8.3 below) is to plagiarize. Plagiarism is where you attempt to pass off other people's ideas as your own. In academic life this is considered a form of cheating as all work submitted for assessment must be your own. That said, academic life depends on engaging with the work of other authors and commentators. In order to do this without plagiarizing it is important to re-present ideas in your own words, acknowledge the sources of the ideas you use and, where you quote directly from a source, provide a full reference. This section of the course takes you through each of these practices.

8.2 Writing in your own words

Active reading, or reading and thinking, are bound up with writing in your own words. If you read materials in a passive way, you are much more likely to copy out chunks word for word when you are note taking, and in the process generate very long notes indeed! Similarly, if you do not spend time thinking about what you have read, asking questions and checking your understanding, you will be tempted to copy out difficult bits or simply try to reorder the author's words. In the latter case you run the risk of changing the whole meaning of what the author is saying in the process. So, in order to develop the skill of writing in your own words you need to read actively, processing meanings as you go.

Activity 10

Have a go at writing in your own words. Actively read the short extract from Hazel Croall reproduced below which focuses on the issue of ‘race’, ethnicity and crime again, but this time explores the issue of police contact. You may need to read it through more than once, but then look away from the screen (or print-out if you have chosen to print the reading) and try to summarize the main points in your own words. Afterwards, click the "Now read the discussion" link beneath the article to read our comments and feedback.

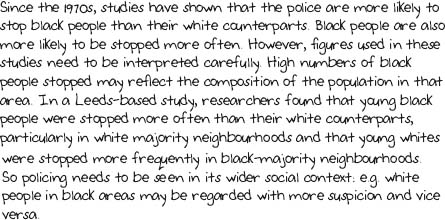

Reading 4