Who belongs to Glasgow?

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 25 April 2024, 6:08 PM

Who belongs to Glasgow?

Introduction

This course focuses on the images of Glasgow and was first presented as a TV programme in 1993. It is not about Glasgow as such; it is about Glasgow's image. Images are representations of places: they are constructed and contested; images also represent multiple identities, uniqueness of place, interdependencies.

There are many different ways of interpreting and representing the character and identity of a place – many different geographical imaginations. Identities of places are a product of social action and of how people construct their own representations of particular places.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of Level 1 study in Sociology.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

demonstrate an awareness of ideas about place and identity using our concept of ‘geographical imagination’ by examining the images that represent a place to reveal how those images came about

show an awareness of ideas about place and identity by examining the images that represent a place to reveal two sets of relationships that are important in understanding the character of a place: power relations and local-global relations.

1 Image of a city

1.1 Why Glasgow?

Glasgow fulfilled our aims and was also an interesting case study having, arguably, been the most successful among British cities in developing/manufacturing a new identity in the ‘post-industrial’ era. Glasgow illustrates:

(a) power relations, reflected in:

constructed images – ‘Glasgow's miles better’ was a deliberate campaign to improve the image of Glasgow.

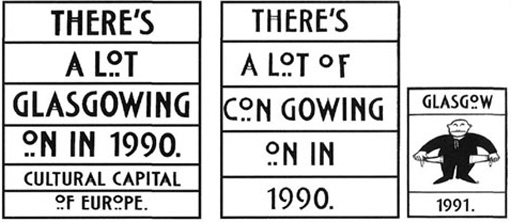

contested images – ‘City of Culture’ – but whose culture?

multiple identities – ‘Clydebuilt’, ‘Red Clydeside’, ‘Shock City’, ‘Glasgow's Alive’ are all images of Glasgow.

whose interests these dominant images represent and whose are ignored.

(b) local-global relations – phrases like ‘second city of Empire’ and ‘a great European city’ reflect how Glasgow's (local) uniqueness has been constructed out of wider (global) interdependence.

1.2 The hard side of Glasgow

Prior to its currently projected image of dynamism, Glasgow was regarded as the place which best illustrated all that was wrong with the modern industrial city: ‘Once called the “second city of the British Empire” because of its size and industrial might, Glasgow had sunk so low that even the locals disdained it’ (Bryson, 1989).

Glasgow's industrial base was laid during the latter half of the nineteenth century when the city became a prominent industrial centre. The idea of ‘Clydebuilt’ serves to illustrate the importance of the city in equipping not only Britain itself, but also the far-flung reaches of the Empire with the ships, locomotives and heavy engineering commodities necessary to fuel economic expansion. Crucially, then, Glasgow's (‘local’) economic fortunes, as with those of many of the other ‘older’ industrial centres of Britain such as Tyneside and Belfast, were integrally tied to the (‘global’) fortunes of the British Empire. The saying ‘Glasgow made the Clyde and the Clyde made Glasgow’ highlights the importance of shipbuilding and, behind that, of trade for Glasgow's industrial growth in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It also illustrates the theme of interdependence. Industrial and economic decline in the period following the First World War, combined with growing problems of inadequate housing, rising unemployment and industrial agitation and militancy, gave rise to the image which arguably has dominated reportage of Glasgow for most of this century. For example:

There is something deeply wrong with the Clyde, … that sends in repeated menace, to every successive Parliament, the same bitter group of extreme left members, irrespective of the changing political mood of the rest of the country, to kill with their fierce interruptions any restful optimism of the remainder of the House.

(Bolitho, 1924)

This image, then, was a product of political agitation and conflict which had gripped much of Clydeside in the early part of this century. The period from around 1914 to the early 1920s, now known as ‘The Red Clyde’, was characterised by large-scale industrial conflict in the shipyards and factories. Community-based agitation over housing conditions gave rise to the 1915 rent strike which was organised mainly by women and received widespread support on Clydeside. Glasgow was regarded as a ‘melting-pot’ during the First World War when the government was increasingly concerned that a potentially revolutionary situation might develop. Glasgow during this period, then, was a very political place and this aspect of its history has also been reflected in many of the images and representations of the city over the decades.

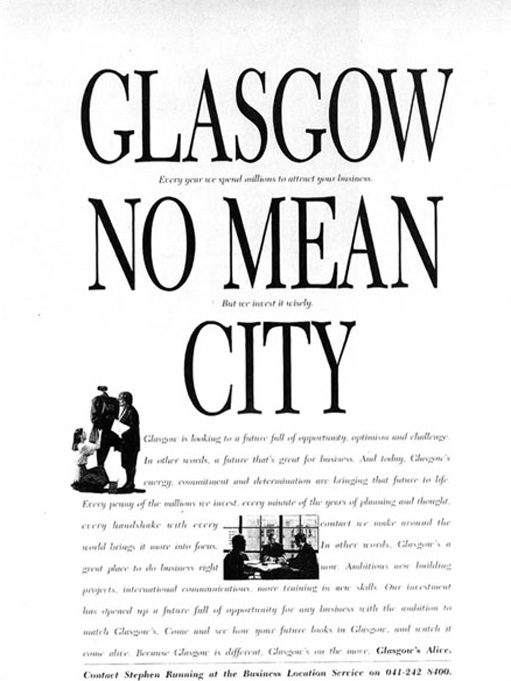

Another image which developed during this period was that Glasgow was a very violent place. This is reflected in the novel No Mean City, written when the city was gripped by the inter-war slump and depression. This image and representation of Glasgow has dominated much of the discussion of the city ever since.

It was reflected in the significant number of novels, dramas, documentaries and television plays which highlighted Glasgow's ‘hard side’. The work of Peter McDougall in the 1970s – an excerpt from which is included in the programme – serves to illustrate much of this negative image. But it is also claimed that this negative image of violence was constructed from outside the city by, among others, media based far away in London/England; it was essentially what others said about Glasgow. Glaswegians knew about these negative characteristics – and that they existed elsewhere as well – but they also knew other things about Glasgow which were never portrayed back to the outside world – that is, until the ‘Glasgow's miles better’ campaign was launched.

1.3 Constructing a new image

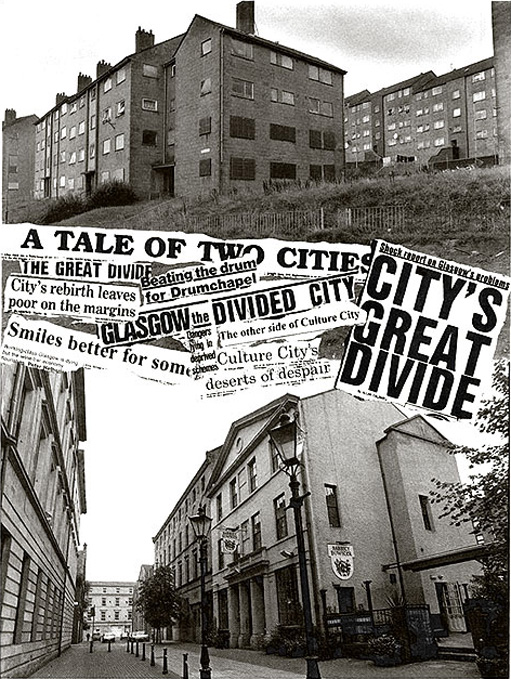

The image ‘Glasgow's miles better’ was deliberately constructed by the City Council, avowedly to make Glaswegians feel better about Glasgow but in fact largely on behalf of business. But it begged a question – ‘miles better for whom?’ Certainly, the city centre was better for shoppers and visitors and the new roads were literally ‘miles better’ for motorists, but the spiralling problems of the housing schemes provided stark counter-images. In other words, as with all images, the image of ‘miles better’ was partial and selective. It was a particular, preferred representation. It excluded other aspects of the city. It was not promoting housing estates like Drumchapel, and they benefited either little or not at all.

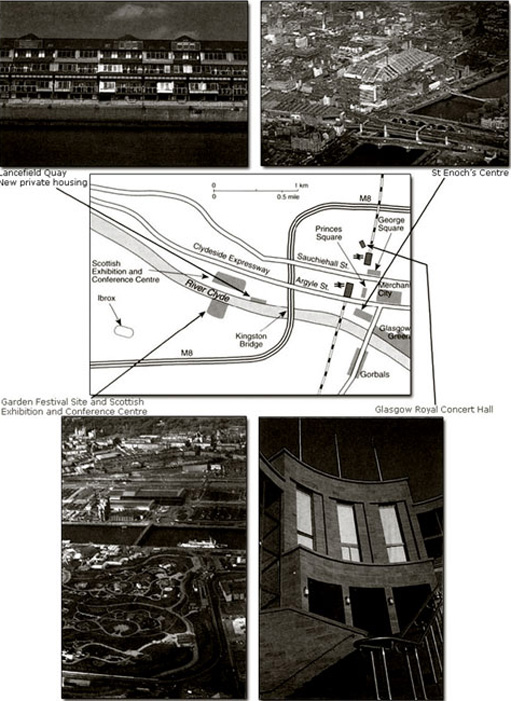

For many people, 1988 marked the arrival of Glasgow on the national scene in Britain, with the National Garden Festival (see Figure 8). For many Glaswegians it proved to be a missed opportunity to gain a lasting amenity, but for those promoting the city it was an important step. In 1990 Glasgow was European City of Culture. By the mid 1990s Glasgow was attracting international conferences (such as Rotary International in 1997 and City of Architecture and Design 1999). But the image of ‘City of Culture’ was particularly strongly contested. On the one hand Glasgow was looking outwards towards Europe in a new way – very different from the late nineteenth and the early part of the twentieth century. From another perspective it was failing to look inwards: the promotion of European and international culture was accompanied by a denial and marginalisation of Glasgow's own local culture. It was also argued that the city would be bankrupted in the process.

The economy of Glasgow has undergone a major transformation since the inter-war period. In common with many other ‘old’ industrial centres, the majority of the city's workforce is now engaged in service sector employment, a far cry from its image as an industrial city par excellence. In part this transition reflects Glasgow's changing position in both the national and international economies. In the 1980s substantial inward investment in the form of business services and tourist-related activities has further altered its traditional economic base. Public and private sector agencies have been to the fore in promoting the city as a place in which to invest and the dominant image of Glasgow is a much more ‘positive’ one. From being a city characterised by violence and conflict, Glasgow is now marketed by the Glasgow Development Agency's Business Location Service as ‘no mean city’ in which to do business. This demonstrates that the same image can provide different interpretations, in this case one negative and one positive. It also serves to reinforce the point that images are built up over time, providing layers of representations. Contrasting images also illustrate the point that at any one time, more than one image or representation will be available. These alternative images frequently conflict with each other and, in different ways, refer to particular readings of previous histories to portray their messages, some of which may be hidden.

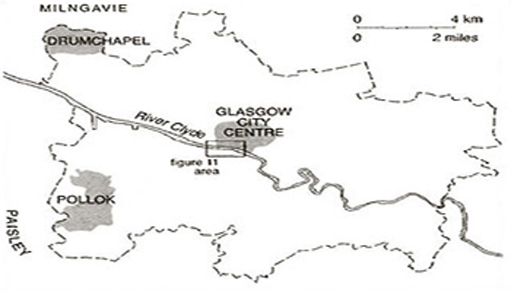

Today's competing images, then, not only compete in relation to contemporary developments and future plans, but also compete in the interpretations of the past of a city such as Glasgow. In Glasgow today, images of a vibrant, modern place, as reflected in the idea of Merchant City, clearly invoke a particular sense of the past. In this respect Merchant City is a particular representation of Glasgow today and one that serves to exclude other images and representations. These contrast strongly with the images of the city's large peripheral housing estates, typified by Drumchapel, which are clearly the product of a very different social and historical context. We can see in this, examples of different ‘envelopes of space-time’, different geographical imaginations. While people in Glasgow often identify with the city itself, different localities within, and competing images of, the city will give rise to different ideas or ‘senses’ of place. Identifying with Drumchapel as opposed to Merchant City or with the city as a whole reinforces the point that senses of place operate at a number of different levels and spatial scales, which may contradict or compete with each other. While spatial or geographical scale clearly refers to identification with particular geographical entities, by ‘different levels’ we refer to the very different class and power relations involved in identifying with a place. It is clear that ‘place’ means different things to different social groups. There are different representations of place at work at any given time, giving rise to competing or contradictory identities with the same place. These, in turn, give rise to counter-claims that the ‘real’ Glasgow is not reflected in Merchant City but in places like the peripheral estates. One of the dominant images to emerge from Glasgow in recent years, then, is the notion of a ‘dual city’: two cities experiencing very different social and economic fortunes in recent decades.

Click here for a larger image.

2 Who belongs to Glasgow? The TV programme

2.1 How the programme progresses

The programme takes the form of a visit to Glasgow. We talked to people and asked about their image(s) of Glasgow and whether these had changed – what was the ‘old’ image; what is the ‘new’; how has it changed; what will it be like in another ten years?

The five main participants have different experiences of Glasgow and these are represented in the images which they hold and aspects of the city's character which they highlight. The themes and ideas behind the programme are all to be found in what they say and what they see.

Gordon Borthwich talks about the long history of Glasgow and denies its violent image as being worse than elsewhere. His perspective highlights what he sees as the city's heritage, which links the past with the present and the future.

Linda Whiteford is part of the city's positive image-building. She sees a place that has always been better than it was painted and sees it now in a very positive, vibrant light.

Jean Forbes sees the urban regeneration process as positive and expects the benefits to ‘trickle down’ to other parts of the city – while acknowledging that this process has been slowed by recession in the economy.

Gerry Mooney points out many of the contrasts in Glasgow's image, or images, and adopts a more critical stance. He discusses the key concepts and themes which provide the framework for the programme.

Edward Stephenson looks, above all, to locality (Drumchapel) rather than to city or region. But he identifies with Glasgow against Belfast, London or Edinburgh.

2.2 Postscript

A headline-grabbing weekend of ‘midsummer madness’, when six murders occurred in (parts of) Glasgow over the weekend of 5–6 August 1995, reinforced the ongoing nature of contestation and debate about the issues discussed in the programme. As noted in The Scotsman (8 August 1995), the legacy of the imagery of No Mean City was quickly resurrected by the press – for example, ‘a darker side to that much-vaunted transformation of Glasgow from No Mean City to Culture City’ (Sunday Times Scotland, 13 August 1995). Others sought to prove empirically that Glasgow's murder rate was the highest in Britain; that the murders occurred in some parts but not in all parts of the city; that violence is closely linked to issues of poverty (Scotland on Sunday, 13 August 1995). A Labour MP declared the need to protect Glasgow's ‘new’ image; others claimed that the success of the image-makers had disguised the hardships still faced by many, pushing die problems of the city to the periphery – in every sense.

This episode futher illustrates the points made in the programme and the notes about the contested imagery and historical basis of competing representations of Glasgow.

Click here for a larger image.

2.3 Watching the programme

Activity 1: Watching the programme

There are two main themes to consider as you watch the programme:

(a) Image and identity

Note down examples of images of Glasgow. What/who is represented? What/who is not represented? Are there different interpretations of the images? Has this image been challenged – how and by whom?

You could use a rough matrix to help in this. For example:

Click here to open a printable matrix for your notes.

(b) Uniqueness and interdependence

What wider (global) relationships have contributed to Glasgow's (local) character/distinctiveness?

Activity 2: After the programme

1. Briefly, try to develop the two themes in Activity 1 in relation to concepts of geographical imaginations, power relations, local-global relations.

(a) Starting with your notes about images:

What do these images contribute to Glasgow's identity?

How have the images been ‘constructed’?

Whose interests have been represented and whose suppressed?

How is this conflict of interests represented?

What do we mean by ‘multiple identities’?

How can a place mean more than just one thing?

What does all this tell us about power relations in Glasgow?

(b) Using your examples of local-global relationships:

How has Glasgow's uniqueness been constructed and reconstructed? What interrelationships have been involved?

In what ways does Glasgow's identity result from ‘what Glasgow is not’?

(c) Note briefly how we have used our concept of geographical imaginations to explore Glasgow's uniqueness.

2. Think about these issues in relation to another place or other places.

What is being represented/promoted?

Who gains and who loses?

3. The main points to grasp from this programme are:

that ‘image and identity’ are central to our geographical imagination;

that images and identities are socially constructed and are not neutral or objective: how we define a place reflects and affects our attitudes towards it and our experience of it;

that images are selective;

that places have multiple identities;

that images and identities are open to and reflect varied interpretations;

that these interpretations may frequently be contested;

that uniqueness of place is constructed out of local-global interdependencies.

Click to watch Part 1 of the TV programme. (5 minutes)

Transcript: Part 1

Click to watch Part 2 of the TV programme. (10 minutes)

Transcript: Part 2

Click to watch Part 3 of the TV programme. (8 minutes)

Transcript: Part 3

Conclusion

This free course provided an introduction to studying Sociology. It took you through a series of exercises designed to develop your approach to study and learning at a distance and helped to improve your confidence as an independent learner.

References

Acknowledgements

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to use the following photographs in this course:

Figure 2 Riveter based on the cover of the exhibition catalogue for ‘Clydebuilt: The River, its Ships and its People’, organised by the Clyde Maritime Trust Ltd.;

Figure 3 Glasgow Herald/Caledonian Newspapers Limited;

Figure 4 Mr Happy adaptation: Mr Men and Little Miss™ and © 1995 Mrs Roger Hargreaves; (all) Courtesy: City of Glasgow;

Figure 5 (left) City of Glasgow; (middle) Courtesy: The Citizen; (right) source unknown;

Figure 6 Courtesy of Corporate Location Magazine;

Figure 7 © Alan Wylie Photographer;

Figure 8 (top left and right, and bottom left) Glasgow Development Agency; (bottom right) © Alan Crumlish.

This extract is taken from D215 © 1996 The Open University.

Course image: amateur photography by michel in Flickr made available under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Licence.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders. If further information can be supplied to amend any acknowledgements, the publishers will be pleased to do so at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out:

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University - www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Copyright © 2016 The Open University