Nationalism, self-determination and secession

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 24 April 2024, 10:18 AM

Nationalism, self-determination and secession

Introduction

This course is based on a chapter from the book Living Political Ideas, which is part of the DD203 Power, Equality and Dissent module. It really attempts to do two things at once. It is about the core concepts and processes with which human groups that think of themselves as nations challenge the existing order and assert their right to a state of their own. And at the same time it is a kind of gentle introduction to how to study political ideas. It is more theoretical, or philosophical, than historical, but that doesn’t mean it has no purchase on the real world. The practical examples with which it works range from the bitter dispute between Palestine and Israel, to the ongoing debates about secession which threaten to break up old multinational states like the UK and Canada. If you have any apprehensions about ‘doing political theory’, I would simply say: there’s no need! Just work through the text, and by the end you will find yourself in possession of some powerful conceptual tools for thinking more clearly and incisively about one of the most urgent political problems of our time.

One thing which is very helpful to keep in mind when discussing ideas in politics is simply the different levels at which ideas can exist and get discussed. Here’s what I mean:

Real world events happen: for example, Palestinians fighting for their own state.

Actors in these events have ideologies or ‘fighting creeds’, which provide them with a source of identity and a justification for their political actions. For example, nationalism.

Journalists, historians and other writers offer explanations of both the real world events and the ideologies in play. For example, Edward Said on Palestine and the wider Arab-Israeli conflict.

Some political theorists make a more abstract and careful analysis of the core concepts, and ‘unpack’ or evaluate the arguments and claims made.

Others go further, offering not only new ways of thinking about the core problems, but practical suggestions for policy-makers. For example, democratic ways of deciding on claims for secession.

One reason this can be hard to think about all at once is that real world events, such as conflicts about secession and self determination, are moving processes (like a film), whilst the analysis of key ideas is a bit like ‘freezing the frame’ and taking a magnifying glass to the words and ideas in play. In studying this course you will be learning an important but quite tricky skill: how to critically examine concepts and theories partly by relating them to the real world.

OK. One final thing before you turn to the course itself. A fundamental assumption of Open University teaching is that it is much more beneficial for a student to work actively with a text than simply to read on and on, passively trying to absorb and remember it all. Sometimes we set in-text activities or exercises to test your grasp of key points, but that is not what we are going to do here. Instead, I recommend the following. If you have the time, make some summary notes as you go along. One good way to do this is to mentally mark what seem to you important passages as you read, and then, at the end of each subsection perhaps, jot down what seem to you the main points you want to remember. At the end, you can check your list of points against that in the conclusion and see how well you have done.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of Level 1 study in Politics.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

grasp the concepts of nation, nationalism and self-determination

have a better understanding of the role they play in current political disputes

think about the problem of how to take democratic decisions about secession

relate political theory to political practice more rigorously

take a more informed and active part in debates about national and international politics.

1 Preface

Political theorists – classic writers such as Hobbes and Rousseau but contemporary ones too – have often assumed a neat fit between this government and that territory and its population, as if the fit between the two were somehow natural or timeless. Reality is always messier than that, of course. Countries, or nation-states, are in part constructed entities or communities – political units that are consciously demarcated and separated from others. As Guibernau comments, ‘In seeking to engender a sense of belonging among its citizens the nation-state demands their loyalty and fosters their national identity’ (Guibernau, 2005, Section 3, emphasis added).

Political theorists have only paid systematic attention to the constructed, engendered aspect of nationhood, and to the ideology of nationalism, in recent years. That is not surprising. For one thing, nations and nationalist movements are all unique in some way. Political theorists find nationalism difficult to generalise about, as opposed to a concept such as ‘legitimacy’ or ‘freedom’. Further, most professional political theorists work in the rich northern countries, where national borders had been stable until the implosion of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s. The creation of new states in the ex-Soviet Union, civil wars over nationalist claims in ex-Yugoslavia, and events such as the splitting of Czechoslovakia between the Czech Republic and Slovakia, raised pressing questions of principle and revived interest in political units, borders and nationalism in countries from Italy to the UK to Spain. This renewed interest was also prompted by the revival of sub-nationalist movements. In the UK, for example, such movements played their role in the pressures that led to the establishment of the National Assembly for Wales and the Scottish Parliament. A number of political theorists responded to the challenging questions raised by these developments. In this course we shall take a critical look at some of the answers put forward, in terms of:

belonging, loyalty, community and statehood

the relationship between individual self-determination and collective self-determination

the range of possible meanings of the idea of the ‘nation’

nationalism as a political ideology

the debate on the ‘right’ to national self-determination: when is secession justified?

2 Political belonging: loyalty, community and statehood

Which people, which group, do you belong to? How do we know who is Them, and who is Us? Where do your political loyalties lie? In a way these are simple questions. There are many contexts in our daily lives when we could answer them well enough. We speak common languages with people around us (and often with the same accent). Many of us live in neighbourhoods and recognise ‘neighbours’ as a distinctive group to which we belong. If we pray regularly in a mosque or church then we might identify ourselves with others as part of a ‘community’ there; if we drink regularly in the local pub or cafe we might feel the same. There can be many, overlapping communities, large and small, and we can belong to a range of them.

What about your primary political loyalty? Many people will happily see themselves and others as fellow British or French or Brazilians or South Africans, whatever other factors may separate them from some of their compatriots. This sense of belonging will generally transfer to accepting the French, Brazilian, etc., government as legitimate, however much one wants to see the policies or the composition of the current government change.

It is easy to say ‘many people’ will be able to identify, and feel comfortable with, their larger political loyalties or belongings (and it's an old trick of political theorists to invoke the ‘many people would …’ defence for what they are arguing). Equally, many will not. People can be ‘caught’ without or between primary political attachments. On the one hand, many societies today are multicultural or multinational, their citizens having diverse, multiple and shifting loyalties. On the other hand, massive movements of people on a global scale have been evident in recent years, for example the movement of Afghanis and Iraqis to Europe and elsewhere in the 1990s and early 2000s in the face of war, oppression and poverty. Such massive movements of people make the experience of indeterminate loyalties and belongings – indeed, statelessness – a common experience. Further, many minority communities within nation-states commonly feel ambivalent about their compulsory primary loyalties, for example indigenous peoples in the USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

Community

‘Community’ is one of the most notoriously ambiguous terms in the vocabulary of politics. It can be and is used to refer to any collectivity or group of people, whether or not that group is large or small, aware of its ‘groupness’ or not, territorially contiguous, inclusive or exclusive, loosely or tightly structured, hierarchical or egalitarian, atomistic or organic, and so on. Politicians are well aware of the word's ambiguity and its feel-good character (how can ‘community’ be a bad thing?), deploying the term to suit their purposes. Social scientists are wary of using the term without due caution, as they are more often aware of the pitfalls that come with its ambiguity and contestability.

Many residents of places such as Macedonia, Kosovo, the Palestinian territories, Cyprus, so-called ‘Padania’ in northern Italy, Catalonia, the western Sahara, Abkhazia, Aceh, Scotland and Quebec live with constant questioning about what should be their primary political loyalty – their nation, or their country. Some will feel that an alien political identity is being imposed on them by a state they regard as illegitimate: the Israeli state in the Palestinian territories, the Moroccan state in the western Sahara, and the Georgian state in Abkhazia. Their literal neighbours may defend with equal vehemence their loyalty to those same states. Although at one level each case is unique, in many such places there is anguished and bloody conflict over legitimacy, loyalty and belonging. Strong sentiments can be fuelled by nationalist agitation and propaganda. Political struggles over land and identity can take the form of ‘border disputes’ at one extreme to ‘ethnic cleansing’ and ‘civil war’ at the other. The impact these conflicts have on the lives of many thousands of individuals and families are well documented (Huysmans, 2005). Nationalism and national self-determination are living political ideas that people do indeed live (and die) for.

The main reason that such conflicts are so important to leaders and followers caught up in them is that to achieve and sustain statehood for one's nation is the ultimate expression of political independence, as it has been since the rise of the modern nation-state around the time of the French Revolution. At that time, the nation-state began, for a complex variety of reasons, to see off its great historical rivals – city-states and empires for example. Beginning in Europe and spreading through colonial conquest and domination, the nation-state has become the basic political unit across the globe (Gieben and Lewis, 2005). Although the fact and the value of its primacy is much debated today, especially by strong advocates of ‘globalisation’, it still provides the fundamental frame through which we understand the government of people and territory. There are local government units within countries and supranational governing institutions ‘above’ them (such as the European Commission and the European Parliament in the EU), but the nation-state is the basic, bedrock unit. There have been different theories about what can make political power legitimate. But when utilitarians, contract theorists, Marxists and others argue about political legitimacy they are almost always arguing about the rightful government of nation-states.

Because statehood is a prized possession, it is hardly surprising that fundamental political questions about ‘them’ and ‘us’ can invite strident answers: most Kosovan Albanians for instance are utterly adamant that they are not Serbs and should not be governed as part of Serbia. No case is that straightforward, of course. Up to the 1990s, Kosovans had not sought independence from Serbia, but rather civil rights. The wars in ex-Yugoslavia provided a context for the emergence of nationalism; other demands transformed into demands for national self-determination. In terms of general principles the case of Kosovo does raise the tricky question: where two or more resolute communities claim the same piece of territory as theirs, where each wants to be governed by people from (as they see it) their own group, who can decide what is right? Are there any broadly acceptable criteria to guide us when we ask who has a right to national self-determination in different cases or disputes?

I want to show how political theory has responded to fundamental questions thrown up by nationalism, the assertion of the right to self-determination, and the closely related rise in secessionist movements. As we shall see, there is no consensus. But theoretical debate has given us some refined and intriguing responses.

Summary

The nation-state remains the main political loyalty in the contemporary world.

National loyalties are placed in question by increasingly multicultural and multinational societies, and massive global movements of ‘stateless’ people.

Struggles for statehood are the basis of many serious conflicts around the world.

We need to ask if there are political theory criteria to guide us in nationalist disputes.

3 Self-determination: individual and collective

The idea of a right to ‘collective self-determination’ is a difficult one – how can a group, as opposed to an individual, have a ‘right’? To argue that a nation has a right to self-determination is, some might argue, to overlook what rights are, and who can claim them.

'Self-determination’ has a positive ring about it – how could anyone oppose it? The idea of self-determination has strong resonances in political theory, dating back as far as Hobbes, at least in England. As European societies over the centuries became gradually more individualistic, so the idea of individual judgement and freedom gradually became more prominent. In the works of the great European political theorists of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the idea of individuals consenting to – choosing, voluntarily – government restrictions on their freedom was crucial. Often political theorists talk of ‘autonomy’ as a principle, underlining the importance of separate, rational, thinking and choosing individuals as the core of political life. The idea of self-determination gets much of its resonance and attractiveness, I suggest, because it taps into this deep vein of thinking about individual rights, autonomy and freedom which runs through the Western body politic up to today.

However, that tradition is about individual self-determination. Even if it is a principle we could all sign up to, transferring it uncritically to a group or collective context creates problems. Can a group be said to have a ‘will’, or to be ‘rational’, in a way analogous to an individual? Can a group make decisions, for example about how to live or who to live with, with the same kind of conviction and clarity that an individual (sometimes) can? The problem is that in a large group there is often no unanimous view on any issue. How many members of a potential group would need to live together in a political community to make that community so legitimate that it could be imposed on dissenters? For example, if there were a 51 per cent vote for an independent Quebec, would that be enough to justify its imposition on the large minority in the province who opposed secession from Canada? If it was 70 per cent would that make a difference? How large or active or vocal does a dissident minority, who want a different community, have to be to challenge that legitimacy effectively? I will pick up some issues of majorities and minorities below; my immediate point is that the very idea of collective self-determination is problematic. Its proponents cannot draw easy support from the idea's linguistic link to the notion of individual self-determination. Perhaps the links between the two are more rhetorical than substantial.

Collective self-determination could mean various things, but most importantly today it means national self-determination: the idea that each ‘nation’ should be self-governing, i.e. it should have its own state. So, for example, Palestinians see themselves as a nation, and seek their own independent state so that they can be self-governing, and not be subject to governance by Israel (or any other state). Many Quebecois – mostly its non-immigrant francophones – regard their primary political loyalty as being to the Quebec nation, and they would like to live in a Quebec that is an independent country alongside Canada, rather than being a province within Canada's federal system.

It is worth noting that this fairly simple picture smooths over some important exceptions and complications. Collective self-determination need not mean outright statehood. It could mean instead some form of autonomy or self-government within another state. Many Quebecois are federalists, rather than nationalists; for various reasons, they prefer Quebec to remain within Canada, even if they favour considerable autonomous powers for the government of the province and special recognition of its francophone culture. Recently, Kurdish parties and leaders have broadly accepted that the predominantly Kurdish regions within Iraq, which might potentially be part of an independent state of Kurdistan, should instead be semi-autonomous regions within the federal, post-Saddam Iraq (see Guibernau, 2005, on definitions of federalism). However, these are exceptions to the rule that national self-determination is normally an aspiration to statehood.

The idea of national self-determination first came to prominence as part of the plans of US president Woodrow Wilson to rebuild Europe after the First World War. His famous Fourteen Points at the Armistice conference in 1918 set in motion a process of national self-determination across the war-torn continent. The Great War had destroyed the Austro-Hungarian empire, Germany, and the Russian and Turkish empires. A new way had to be found to organise government in the region. Wilson saw himself as involved in a process of constructing nations, and indeed many new states were created from the ex-empires. Some, such as Poland, were states based more-or-less on a group with a recognisable and felt common culture. Others, such as Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia, were multi-nation-states, which dissolved into the constituent nation-states more recently (between 1992 and 2003, Yugoslavia broke into Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Serbia and Montenegro; in 1992, Czechoslovakia divided into the Czech Republic and Slovakia in the so-called ‘velvet revolution’).

After the Second World War, a new wave of national self-determination accompanied the process of decolonisation. Across Asia and Africa, through the 1950s and 1960s, several new independent states were formed out of the former British, French, Belgian, Dutch and Portuguese empires. This wave usually kept intact the political units that together made up empires; though there were major exceptions, such as the break-up of India into the two states of India and Pakistan (and later into three states, with east Pakistan becoming Bangladesh in 1971).

The meaning and application of the idea of national self-determination has evolved during the course of the twentieth century. Most recently, as we have noted, after the end of the Cold War, there was a strong revival of interest in national self-determination among political theorists and international legal theorists. Today, with many ‘nations without states’ asserting their right to self-determination, what can political theory tell us about identifying nations and specifying principles (and practices) of national self-determination?

Summary

National self-determination is one type of collective self-determination.

The idea of collective self-determination gets much of its force from the analogy with deep-rooted ideas of individual self-determination or freedom; but shifting too easily from the individual to the collective can be problematic.

A demand for national self-determination may not be a demand for outright statehood.

The idea of national self-determination gained special prominence after the First World War.

Interest from political theorists has been revived by the pressing nationalist demands in eastern Europe and elsewhere after the end of the Cold War.

4 What is a ‘nation’?

Guibernau (1996, p. 47) has defined the nation as: ‘a human group conscious of forming a community, sharing a common culture, attached to a clearly demarcated territory, having a common past and a common project for the future and claiming the right to rule itself’. So awareness, territory, history and culture, language and religion all matter. However, it is rare in the real world to find a case of a nation with a clear-cut and homogenous character in terms of this list of possibilities. Each nation is unique in the (alleged) makeup of its special character and worth. One crucial question is whether – and to what extent – a group must be aware of its alleged distinctiveness from other groups, in order to be classed as a nation. One could argue that a nation can objectively be defined as a group of people which possesses a shared and distinct, historically persistent cultural identity, and which makes up a majority within a given territorial area. If that is the case, then one could argue that even if such a ‘nation’ is not pushing for a right to self-determination (in any form), it nevertheless is a nation.

There are other would-be objective approaches to what might signify nation-ness, including statehood, ethnicity and naturalness.

Statehood. This view holds that if a group has its ‘own’ state then it constitutes a nation. The common term ‘nation-state’ taps into this sense of nation. But this approach seems a little too neat, and begs many questions. For a start, it would mean that there can be no non-state nations, freezing into place the existing configuration of states that makes up the political map of the world. Defining nation-ness in terms of statehood, although common, rather rigs the game – why should all non-state ‘nations’ have their aspirations dismissed purely by definition?

Ethnicity. Some interpret the principle of national self-determination as meaning that each ‘ethnic’ group forms a nation, and that each nation should be presumed to have a right to political self-determination. But who is to locate – and worse, to police – where the boundaries of one ethnicity stop and those of another begin?

Naturalness. Mountains and rivers, for example, are sometimes thought to provide ‘natural’ borders. But, just as much as they divide and separate peoples, mountains and rivers and other features of the natural landscape can bring people together and create common interests and a common sense of community. There is no single or correct way to ‘read’ the social meaning of natural landscapes.

Figure 2

We can see that the problem with so-called objective approaches to defining a nation is finding sound criteria by which one might judge which groups form nations and which do not. How can we weigh different histories, traditions, religions, languages? Any attempt at objective demarcation of national communities is sure to remain contested, not least from among the groups who are thus classified.

This is why most theorists and observers adopt a subjective approach to defining nation-ness. From a subjective point of view, history, religion and language, for example, still count, but awareness and acceptance of a claim that X is a nation among the people of the supposed national group – a real consciousness that this is a group and I am part of it – is the crucial ingredient. This raises an important further question: does the awareness constitute the group, or the other way around? Certainly, a sense of nation and national belonging can be induced and engendered, ‘created’ if you like. Films, paintings, speeches and activities can invoke national heroes and national myths, which in turn can induce a sense of commonality and belonging. It normally serves the interests of those doing the inducing to say that they are merely reflecting what is already there, mirroring people's pre-existing and deep-rooted feelings of attachment. All of this is routine and familiar, on one level. All governments regulate, to some degree, citizen education, language, culture, sport, travel and so on, and by so doing they establish and reinforce some ‘national’ attributes and discourage others. But extreme, simplistic and coercive peddling of dubious ‘national’ myths for cynical power purposes is common enough also. Hitler's Nazism and Mussolini's Fascism were primary twentieth-century examples, but there are many others. As we shall see further below, nationalism has a dark side. It involves inevitable shoehorning of a people under a simplified set of cultural or other characteristics. The degree of this shoehorning and the way it is carried out are important.

From a subjective point of view, to quote Margaret Moore,

the term ‘nation’ refers to a group of people who identify themselves as belonging to a particular nation group, who are usually ensconced on a particular historical territory, and who have a sense of affinity to people sharing that territory. It is not necessary to specify which traits define a group seeking self-determination.

(Moore, 1997, p. 906)

Moore goes on to say, echoing our discussion above, that

One advantage of conceiving of national identities in subjective terms, and jurisdictional units in terms of the area on which the national group resides, is that it avoids the problem of contested definitions of what really constitutes a nation.

(Moore, 1997, p. 907)

We are able to sidestep all such awkward definitional issues and come down to the view that ‘Ultimately, communities are nations when a significant percentage of their members think they are nations’ (Norman, 1991, p.53). One consequence of this view is that imagination and symbolism become essential for defining a nation in the mind of its (potential) members. Before turning to the issue of nationalism as a political ideology, I want to say something brief on this critical point.

I propose the following definition of the nation: it is an imagined political community. … It is imagined because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion.

When it comes to defining a particular nation, potent mixes of historical fact and myth are common: ‘“to forget and – I will venture to say – to get one's history wrong are essential factors in the making of a nation” [Renan] and “Nationalism requires too much belief in what is patently not so” [Hobsbawm]’ (quoted in Archard, 1995, p. 472). Beliefs do not need to be true for people to hold to them and act as if they were true; ‘A group of individuals united in and by the false belief that they share a common history might act collectively and thereby initiate a common history’ (Archard, 1995, p. 475).

There is plenty of scope for the making of representations, in the form, for example, of constructing and presenting national myths which can be fuel for imagining communities in Anderson's sense. Anderson took the view that ‘communities are to be distinguished, not by their falsity/genuineness, but by the style in which they are imagined’ (Archard, 1995, p. 481). Clearly, not any old claim to nationhood could ‘stick’ – ‘the nation-constituting beliefs must bear some kind of possible relationship to the group of people who are constituted as a nation’ (Archard, 1995, p. 474) – but would-be nation builders would have plenty of scope to discourage some narratives of nation and to encourage others.

One might argue that a nation not only imagines itself, others imagine it too, and offer constructions or representations of it as a friend or as an enemy. These ‘imaginings’ matter. Consider, for example, the Israel/Palestine issue. Some Palestinians portray Israel as a tool of Western imperial power in the Middle East, and Israelis protest at such images. On the other hand, consider the argument of the Palestinian critic Edward Said:

What we must again see is the issue involving representation, an issue always lurking near the question of Palestine … . Zionism always undertakes to speak for Palestine and the Palestinians; this has always meant a blocking operation, by which the Palestinian cannot be heard from (or represent himself) directly on the world stage. Just as the expert Orientalist believed that only he could speak (paternally as it were) for the natives and primitive societies that he had studied – his presence denoting their absence – so too the Zionists spoke to the world on behalf of the Palestinians.

(Said, 1979, p. 5)

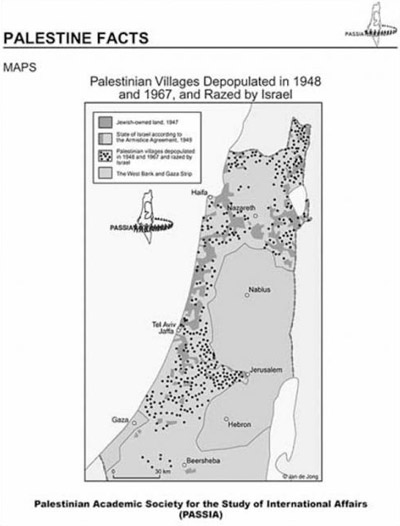

Maps, too, have proven to be a vital part of ‘imagining’ a nation, in quite a literal sense, creating a visual ‘image’ of a nation as a state. Maps establish, indeed they create, centres and peripheries, locations and borders, and even the very existence of a political unit. Nation-builders know this fact all too well. For example, in the words of Weizman:

From 1967 to the present day, Israeli technocrats, ideologues and generals have been drawing maps of the West Bank. Map-making became a national obsession. Whatever the nature of Palestinian spatiality, it was subordinated to Israeli cartography. Whatever was un-named ceased to exist. Scores of scattered buildings and small villages disappeared from the map, and were never connected to basic services.

(Weizman, 2002)

Figure 3

Click to view a larger version of .figure 3 https://www.open.edu/openlearn/ocw/mod/resource/view.php?id=26361

Figure 4

When one looks more closely at the sheer diversity of those entities that we call ‘nations’ and ‘states’, the strong view expressed by anthropologist Clifford Geertz becomes understandable: ‘The illusion of a world paved from end to end with repeating units that is produced by the pictorial conventions of our political atlases, polygon cut-outs in a fitted jigsaw, is just that – an illusion’ (Geertz, 2000, p. 229). Geertz does not deny the material existence of different political systems and the material reality created by the policing of national borders, for example. But he does want us to question whether these separate splashes of colour in atlases really add up to any strong commonalities between the separated political units.

Finally, it is worth pointing out a quite different, provocative perspective that emerges once the symbolic aspects of nation are accepted, as part of a subjective approach to the definition of nations. One could argue that a nation is not something that ‘is’, but rather it is something that ‘does’. What does it mean, what effect is intended or achieved, by calling a group of people a ‘nation’ (as opposed to a community of some other sort)? Instead of thinking of ‘culture’ or ‘descent’, for example, as fixed things, we can ask how different definitions of the nation work or what they accomplish (Verdery, 1996). A nation is a system for classifying people, as are class, gender and so on. We often take these classifications to be ‘natural’ – ‘nation’ and ‘natural’ possess a common etymological root in the sense of ‘to be born’ – but they can equally be seen as constructed. Classifications are vital to establishing political centres and peripheries on the ground; they are constructions that do real work, and upon which people act. Notice also how seeing ‘nation’ as a symbol and a construct makes it a dynamic concept. After all, if ‘nation’ is a label, it can in principle be peeled off one jar and put onto another. There has been talk of the ‘Arab nation’, for example, over the years, a term used to symbolise a commonality of interest and outlook among Arab peoples regardless of which nation they belong to in the sense of ‘nation-state’. A very different example of the dynamism of this label would be the more recent use of the term in the phrase ‘queer nation’, invoking a sense of commonality among gay communities regardless of what country they are citizens of. This dynamism is clearly one part of what it means for a political idea to be ‘living’.

Summary

There are two main approaches to the definition of nation, the objective approach and the subjective approach.

The subjective approach is generally favoured by theorists.

Symbolic and imagined aspects of nationality are important.

‘Nation’ as a word and a label is still evolving, and being applied in new contexts.

5 Nationalism as an ideology

5.1 Ideology: a contested concept

Propagators of ideologies use images and symbols to get people to believe and act in certain ways. Nationalism as a political ideology uses the idea of ‘nation’ to achieve political goals, and may be the most potent ideology in existence. It is worth reflecting for a moment on what kind of ideology it is. And it is worth reminding ourselves that ideology is a contested concept; a term that can mean different things. Marx and Engels subscribed to the notion of ideology as a set of ideas that induce false consciousness in workers under capitalism. A second sense of ideology is that set of left and right ideologies we hear about in day-to-day politics: communism, socialism, liberalism and conservatism, for example. Nationalism, we could say, represents a third type of ideology. It is not easy to locate on the left-right ‘ideological spectrum’, though today nationalist rhetoric, generally speaking, is something more often heard from the political right. It is concerned with creating or maintaining the very political unit that the left-right ideologies need to ply their trade in the first place. One could pursue socialist or conservative strategies without reference to national governments, but most often they are thought of, and pursued, in terms of government policies for nation-states. So, nationalism is a political ideology, but a distinctive one. In a sense, if a nationalist ideology is successful it makes possible the pursuit of other ideologies in the sense of ‘left’ and ‘right’ policy prescriptions.

According to Michael Freeden (1998, pp. 751–2), the five elements which constitute the core structure of nationalism are:

‘the prioritisation of a particular group – the nation – as a key constituting and identifying framework for human beings and their practices’

‘a positive valorisation is assigned to one's own nation, granting it specific claims over the conduct of its members’

‘the desire to give politico-institutional expression to the first two core concepts’

‘space and time are considered to be crucial determinants of social identity’

‘a sense of belonging and membership in which sentiment and emotion play an important role’.

Freeden does not discuss explicitly issues of centre and periphery, but notice how the imagining, creation and institutionalising of centre-periphery relations is critical in this account. The second point puts forward one's nation as a core of value; the third is about the creation of varied markers of centre and periphery; borders, government institutions and others that embody, and which make real, what the ideology has imagined.

Freeden rightly warns that this set of concepts cannot be used to explain a great deal in itself. It is necessarily a highly abstract set of elements, which need filling out with particularities of specific cases and elaboration using other concepts. Nevertheless it provides a useful frame for exploring the texture of nationalism as an ideology. We will consider four of these elements in turn (discussion of space and time, the fourth element, is implicitly covered in the discussion of the others).

5.2 ‘The prioritisation of a particular group – the nation – as a key constituting and identifying framework for human beings and their practices’

No particular form of articulating the nation is required by the formulation of this first element; the nation might be ‘imagined’ or ‘constructed’ as homogenous or as pluralistic and diverse, for example. However nationhood is imagined, though, it will invariably involve some form of suppression of alternative ways of classifying peoples. Consider that for most of us there are linguistic, class, ethnic, location, gender, religious and other aspects to our identities. If nationalists want to subsume all these under nationality as the primary marker of identity, we might have grounds to suspect the move. Often, observers distinguish liberal nationalism from illiberal nationalism. The former embraces the plurality of the sources of identity, while the latter subsumes other aspects under nationality Consider briefly three alternative ways of constructing or classifying political ‘community’, which may either cut across or reinforce nationalist classifications:

(a) ‘Functional’ communities. People often identify with functional rather than territorial groups. Class solidarities, for example, which arise from people's positions within the relations of production of a country (or a region, or indeed within the global economy), can and do cut across national and other territorially based solidarities. Marx, to cite the most prominent example, knew this well: ‘Workers of the world unite!’ was precisely a call for workers everywhere to unite against the exploitative conditions they shared, regardless of national or other attachments.

(b) Religious communities. Religion can operate like class in that it can establish and activate loyalties that owe little or nothing to territorial location or boundaries. Often a dimension of time and circumstance can transform religion, along with gender and class for example, from a subversive to a reinforcing element within nationalist discourses. In the Algerian war of independence from France in the late 1950s, for example, Islam was undoubtedly a reinforcing element within Algerian nationalism, albeit largely secondary to the secular and socialist character of the main liberation movement, the FLN. More recently, with the resurgence of a particular form of political Islam – another ideology, relatively recent on the global scene and powerfully important in the wake of ‘9–11’ – against the perceived corruptions of the governments of Algeria and a number of other Arab states, a particular interpretation of one religion has become a deeply subversive element.

(c) Regional and global community? It is a source of irony for some commentators that a resurgence of nationalism after the collapse of communism in Russia and in Eastern Europe has come at a time when the primacy of the nation-state in some key respects is being challenged by something called ‘globalisation’ (see Gieben and Lewis, 2005; Guibernau, 2005). According to some influential views, globalisation does involve large-scale trends which add up to a significant challenge to our dominant national conceptions of political community. David Held (2000) has recommended that we adapt democracy so that new ‘constituencies’ that cross national boundaries can be recognised and their members participate in decision making on cross-border issues. He and others have also advocated global government through a world parliament and other institutions. Such views see the community as made up of those affected by certain actions or phenomena, regardless of their territorial location and loyalties. It is people affected by, for example, AIDS, acid rain and global warming, who form a new sort of ‘constituency’ and a new type of collective interest. The concern here is about people in different countries, drawn together in new forms of ‘political community’ by having a stake in the outcome of pressing cross-border issues, and the need to downgrade more rigidly national-territorial (and to some degree also legal) definitions of political community.

Figure 5

5.3 ‘A positive valorisation is assigned to one's own nation, granting it specific claims over the conduct of its members’

Just how a nation is prioritised over other communities will have an important impact on how the terms of this second element are played out. A nation that sees itself in pluralistic or liberal terms for example – which may celebrate cultural diversity as part of its very sense of a collective identity – is, on the face of it, less likely to make particular demands or to institute extensive controls on the behaviour of its members. On the other hand, a nation that is imagined in terms of the more monolithic view of a more homogenous culture will be more likely to be directive in its treatment of its members. Apart from ‘loyalty demands’, valorisation may also encompass ‘superiority claims’ which hold that other peoples, ethnic groups or nations are inferior in some respect. There is no necessary connection between racism and nationalism. Nationalist trends in the older democracies of Europe – the success of Front Nationale leader Jean-Marie Le Pen in becoming one of the final two candidates in the run-off for the French presidency in 2002, and the rise in votes for the far right in Switzerland, Austria, Denmark, Belgium and The Netherlands – do hint at or openly articulate such claims. More progressive forms of nationalism, which were more common throughout the process of decolonisation in the twentieth century, generally did not do so.

5.4 ‘The desire to give politico-institutional expression to the first two core concepts’

There is a strong case for regarding the third element in the ‘core structure’ of nationalism as the key one. Generally, as we have seen, nationalists want their nation to have a state, or statehood. But political self-determination might have other outlets.

From the comparatively ‘soft’ demands to harder and less compromising ones, the spectrum might consist of some form of:

- recognition of the cultural distinctiveness of a ‘national’ minority community within a state, accompanied by institutions (cultural councils, a dedicated ministry, and so on) which sponsor the interests of that group (think of the ‘first nations’ in Canada)

- cultural federalism, where specific functions such as education are handed over to recognised ‘national’ or cultural groups for them to run on a semi- autonomous basis within an existing state

- regional federalism, where a territorial group has the right to run its own affairs substantially within a particular location within the state

- embryonic and possibly transitory 'statehood’ which might not be territorially continuous but may involve the promise of substantial degrees of autonomy (as with the Palestinian Authority)

- embryonic statehood under temporary international (normally UN) tutelage and protection, as in East Timor and Kosovo after the violent conflicts in both places

full independent statehood and recognition as such from other states and international bodies.

Different demands for national self-determination could lead to any one of these, or a combination of them. Some commentators are wary that demands for strong forms of national self-determination might be met (by colonial powers for example) with co-optive strategies, offering a lesser degree of autonomy in the hope of buying off or defusing the autonomy demands. Avner De-Shalit, for example, makes the point that the demand for self-determination is a political and not a cultural demand. Discussing the case of Palestine, he makes the case that cultural autonomy would not be enough to satisfy Palestinian demands, in theory or in practice:

Autonomy may be the solution to something but not to the Palestinian demand for national self-determination. The demand is political, and it therefore requires free institutions and a grass-roots democracy with active and meaningful participation, enabling Palestinians to determine their own rules, form independent foreign relationships, do business using their own currency, and have their own history of independence. All this is lacking in the solution of autonomy.

(De-Shalit, 1996, p. 916)

The importance of ‘giving expression’ to the political aspirations of one's own nation is clearly evident in how important the ‘trappings of statehood’ are – to aspiring states and existing ones. Consider, for example, disputes over the draft constitution of the EU in 2003 (the constitution was signed by European leaders in October 2004). The UK government was concerned about its sovereign statehood, and sought to expunge the word ‘federal’ from the draft, which included the statement that the EU ‘shall administer certain common competences on a federal basis’ (cited in Castle, 2003). Federalism does imply decentralisation, which is why many other countries in the EU don't mind it. But it also implies that the EU would be a state-like entity, despite policy decentralisation. For the UK government it was a challenge to the notion of the EU as a union of states. Giving expression to one's nation can stretch to retaining expression of those things that make it a nation-state. Prime Minister Tony Blair made this clear at the EU summit set up to finalise the new constitution when he said:

Of particular importance to us is the recognition – expressly – that what we want is a Europe of nations, not a federal superstate…. Taxation, foreign policy, defence policy and our own British borders will remain the prerogative of our national government and national Parliament. That is immensely important.

(Black and White, 2003)

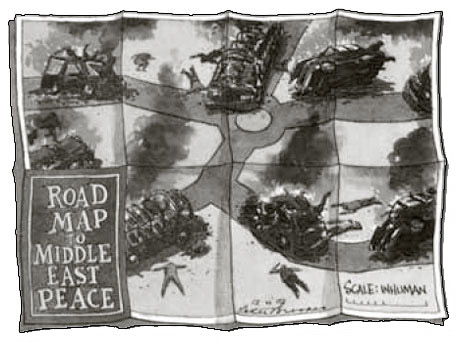

To the Palestinians, for example, the trappings of statehood are vital from a quite different angle. Presenting the ‘halfway-house’ institutions of the Palestinian Authority as a sort of embryonic statehood has been important. As the post-Iraqi war context led to the US-sponsored ‘road map’ for Middle East peace, there was a sense that ‘Palestine’ both exists as a political entity – as a ‘state’, to be more precise – and that it did not. There is a ‘Palestinian Authority’ (though not called a ‘government’); and there is a ‘Palestinian Legislative Council’ (though it is often referred to as a ‘quasi-parliament’, implying that it is not a real parliament, i.e. part of a real government of a real state). The late Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat had the ‘chairmanship’ of the PA, but he was not a ‘president’. But the PA does have a ‘Prime Minister’ – a position which has been occupied by Mahmoud Abbas and Ahmed Qureia. Here we have a desire on the part of Palestinians and the other sponsors of the peace process to name and operate institutions and offices which look and sound state-like.

5.5 ‘A sense of belonging and membership in which sentiment and emotion play an important role’

Nationalism is about land or territory and what it means to people. Nationalists make claims to the centrality of certain tracts of land to them, to their people, to their collective history, traditions, cultures and sufferings:

When a hundred thousand nationalists march down Sherbrooke Street [in Montreal] chanting ‘Le Quebec aux Quebecois’, they are not just talking about the establishment of a public language or about the protection of Quebecois culture. They are talking about a whole relation between a people and a territory and the future.

(Walker, 1999, p. 155)

Emotional attachment to land takes on various shades in debates about nationality and community. As we have seen, it is material, economic and symbolic, all at once. It is about ownership and appropriation, inclusion of one's own nation and exclusion of others. Naming is a critical part of this, a fact that is clear in the example of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict:

Some Arab villages in pre-1948 Palestine that were abandoned during the 1948 War were renamed with Hebrew equivalents leading to contestations over municipal rights; the Arab village of Ein Houd, for instance, was re-established in 1953 as the Israeli artists’ colony Ein Hod.

(Sucharov, 1999, p. 185)

Indeed, more generally, attachment to land, and imbuing of land with loaded symbolic meanings, is a core aspect of this conflict. Palestinians (and all Arabs), for example, call Jerusalem al-Qods, which translates as ‘the holy’, imbuing the city with special spiritual-political significance; a spiritual as well as a political and geographical centre of Palestine. Similarly,

To nurture their historic claim to Zion throughout the centuries, Jews have had to call up historical narratives and national symbols to strengthen the imagined link between the people and the land. Jews have historically sung folk songs about returning to Zion, and the Jewish liturgy contains references to the sanctity of Jerusalem and the land.

(Sucharov, 1999, p. 186)

Note too that borders and boundaries do not have to be understood as they normally are: fixed entities with clear meanings and consequences. Recent analyses, for example, have explored national boundaries as ‘complicated social processes and discourses rather than fixed lines’ (Paasi, 1999, p. 73). One can argue that boundaries do not persist by virtue of their being drawn on agreed maps, but primarily through daily practices which enact and reinforce them; from checkpoint controls to signs, for example. Further, our notion of what really constitutes ‘boundaries’ needs to be flexible to capture a raft of daily political realities, as the work of Huysmans (2005) with respect to asylum seeking testifies. In a similar vein, but in a very different context, consider what historian Rashid Khalidi calls ‘the quintessential Palestinian experience’, which ‘illustrates some of the most basic issues raised by Palestinian identity’ … [and which] takes place at a border, an airport, a checkpoint: in short, at any one of those many modern barriers where identities are checked and verified. What happens to Palestinians at these crossing points brings home to them how much they share in common as a people’ (Khalidi, 1997, p. 1).

In this section we have explored the different dimensions of nationalism as an ideology. We now turn to ways in which political theorists have tried to deal with the issue of principles for national self-determination and secession.

Summary

Nationalism is a particularly potent ideology, arguably different from other forms of ideology.

Freeden sets out various elements of the core structure of nationalism, which help to frame debates about and discussions of the idea and its practice.

6 National self-determination

6.1 When is secession justified?

By valuing a group positively and seeking self-determination for it, nationalists often set out to redraw maps, to create new countries or to reinstate old ones. It is rare for this to occur without (often violent) conflict. Can political theorists offer guides to dealing peacefully with such disputes?

One question which political theorists have focused on has been that of secession. Secession as an issue carries with it most of the dilemmas associated with nations and nationalism, and whether theorists can say anything useful in terms of rights and wrongs. In cases of dispute, how might one decide which communities should be self-governing?

Surprisingly few political theorists have paid sustained attention to this problem. One exception has been Frederick Whelan, whose search for a satisfactory guiding principle ended in a pessimism that is evident when he writes that: ‘it appears that our only choices are to abide by the arbitrary verdicts of history or war, or to appeal on an ad hoc basis to other principles, none of which commands general respect’ (Whelan, 1983, p. 16). Nevertheless, vigorous debate continues. Let's map some of the approaches theorists have taken.

Consider a country we can call ‘Y’, which consists of three different groups: the As, the Bs and the Cs. The most numerous group are the As, making up 60 per cent of the population. The Bs make up 30 per cent and the Cs 10 per cent. We could look at country Y and ask: which communities should be self-determining here?

The first response might be that it simply does not matter as long as country Y is democratically governed. Separating out or combining together different cultural communities makes no difference because if the state is democratic everyone has full rights to liberty and basic equalities anyway. This is a provocative view, one that liberals (who see people as essentially the same underneath their outward differences) often find attractive. But the fact is that people do feel identification with others, and often wish to be governed with, and by, particular others, people from ‘their’ group. As we have seen, the recasting of the world political map after the end of the Cold War forced many more theorists to address issues of nationalism and community.

A second response might be to find objective criteria to distinguish one political community from another, and apply them. But we have seen the very real difficulties in trying to construct ‘objective’ indices.

So what other approaches are there if we accept that the issue can't be ignored, and that we need to take a subjective approach to it? A more promising third response among advocates of democracy has been to search for democratic answers to these dilemmas. We could ignore democratic mechanisms and just say ‘leave it up to the people in Y, they'll work it out’. But we would be right to be wary of coercive means (such as ‘ethnic cleansing’) to determine which political communities should be self-governing.

Democracy is often taken to mean ‘majority rule’, or sometimes ‘majority rule, minority rights’. Often, however, writers on the subject have ignored the prior question; ‘majority of which group of people?’ We are caught in a vicious circle, it seems, where the people cannot decide who are ‘the people’ (or who constitutes ‘the nation’) until we know who the people are who can decide!

Some theorists have suggested ways out of this vicious circle. Consider country Y again. If groups A, B and C are all governed within Y as one state, and there is no significant dispute about the legitimacy of Y, then issues do not arise. But what if Bs want to secede and form their own state? What could make their secession legitimate?

The democratic theorist will answer: democratic majorities. So if a majority of people in B vote for an independent state, it should be granted. Democratic theorist Robert A. Dahl emphasises the point that the would-be new state should itself be a democracy, and most would be happy to add that criterion (Dahl, 1989). But again, there are some tough questions that need to be addressed.

6.2 Who should get to vote on secession?

The Bs (encompassing the Cs) or all the As too? After all, democracy is often said to be about people who are affected by an issue having a say on it; and As will certainly be affected if Bs secede. This is a live issue with regard to Northern Ireland's future, for example. If a referendum were to decide if the province should join the Irish Republic, should the voters include all UK voters and all Irish voters, or just those living in the province? If, for example, there were to be a vote on the creation of an independent Palestinian state, what would be the appropriate constituency: (a) Palestinians living in the occupied territories, which might become the state, or (b) these plus Palestinians living elsewhere (the ‘diaspora’), and/or (c) those living in the occupied territories plus Israeli citizens? Clearly, the answers to these questions are politically critical.

One writer on secession, Harry Beran, has proposed that there should be a series of votes in such difficult cases. The proposed boundaries of a would-be new state could be expanded or contracted slightly from one vote to the next. The idea is to maximise the number of people who live in a political community of their choosing. For example, if some of the people of Northern Ireland wanted to vote to leave the UK and join the Irish Republic, a series of votes could be held on the issue. In each subsequent vote, the boundaries around the voting group could be expanded or (normally) contracted in order to maximise the percentage of people desiring the change. But while this ‘solution’ might maximise the number of people being able to belong where they choose, it does have its problems. One is that in principle it favours secessionists over integrationists, whereas there may be reasons not to allow the stability of existing arrangements to be upset so fundamentally. Perhaps more importantly, it may only work well where a would-be secessionist group occupies a continuous slice of territory. Where a group is interspersed among others who do not wish to change the status quo, the dangerous spectre of significant and forced population movements raises its head. The deaths as people moved east and west with the creation of Pakistan in 1949 offer a stark reminder of those potential dangers.

6.3 What size of majority vote should decide the issue?

In many types of democratic vote, a bare majority (technically, 50 per cent +1) is enough to decide outcomes. But often constitutional changes – changes which would affect the basic structures or political rules of the game – are regarded as needing ‘supermajorities’ of, say, 60 or 70 per cent. A basic change in the sovereign political unit would certainly count as a constitutional change. If the Bs get to vote, we might be concerned if only a bare majority favoured secession, especially if the voting turnout was low. Because the Cs form a minority within the B community, should we look for a majority of Cs as well? In addition, the turnout might be a special issue for such significant constitutional changes.

6.4 Does one community seceding grant a similar right to others?

Consider the position of community C. If B secedes, it takes C with it into the new state. But does C then have the same right to secede from B? Consider the case of Quebec. Quebecois separatists have come very close to achieving the bare majority needed to achieve their goal. But if they gained the right to secede from Canada, would other groups who do not see themselves as a part of a francophone entity likewise have the right to a further independence vote for themselves? What about non-francophone immigrant communities, or indigenous ‘nations’, within Quebec? If one secession, democratically sanctioned, is acceptable, then why not other, subsequent or consequent ones? Some theorists who broadly accept a democratic model of secession still worry about a ‘domino effect’, where one secession will provoke others, and we will end up with a patchwork quilt of ever-smaller political units (or countries). I return in a moment to the question of whether there are good reasons for us to be so concerned about the size of nation-states.

6.5 Do our answers depend on who the groups are?

Finally, perhaps our intuition about how to deal democratically with country Y depends on who we think the As, Bs and Cs are. Consider three possibilities:

(i) A is the UK, B is Scotland, C is the Shetland Islands

(ii) A is the EU, B is the UK, C is Scotland

(iii) A is a world government, B is the EU, C is France.

Does your intuition about the rights of communities A, B and C shift from case to case? If so, is the shift due to a reflex to favour the sovereign, self-governing status of existing nation-states? Or is it because you favour decentralisation in principle, or because you are an advocate of ‘ever closer union’ in the EU, or indeed of world government? Perhaps exploring our intuition in this way tells us something about the uses and limits of political theory. We must be careful to examine the assumptions we bring to our analyses, and be sensitive to the assumptions of the theorists we read.

6.6 What about a more restrictive ‘remedial right?’

Some theorists, such as Allen Buchanan, favour placing higher hurdles in the path of would-be secessionist movements. Rather than endorsing some rather permissive form of democratic right to national self-determination, he favours a more restrictive remedial right. Only those ‘national’ groups who can show that they suffer systematic historical injustice, or have so suffered, have a strong case for independent statehood. In one sense, this approach takes us full circle; if there is no great injustice, and if a minority ‘national’ community (Bs or Cs, for example, in country Y) is governed in a largely democratic manner, then we ought to favour the status quo.

6.7 What about alternatives to secession?

We have seen that in principle there are alternatives: cultural autonomy or a form of federalism. There are alternative ways to recognise 'national' identity apart from secession.

One conclusion to arise from this discussion of secession is that we are not cast adrift without any general principles or guidelines. We have also seen how the complexities of the real political world impinge upon political theories, and how those theories in turn can help us to make sense of the world. Debates among theorists about secession may highlight how worried these theorists are about nationalism. There are versions and examples of nationalism which are anything but liberal and tolerant of others (perhaps Serbian nationalism is a contemporary example). There are others where, arguably, the opposite seems to be the case (Scottish or Quebecois nationalism might be examples). Looked at through the lens of illiberal nationalism, ‘permissive’ theories of secession, like the stronger democratic theories we looked at, may raise concerns. After all, the democratic theories may end up endorsing either ethnic cleansing or systematic colonisation. The ethnic cleansing involved in efforts to create ‘Republic Serbska’ in Bosnia in the early 1990s would be an example of the former strategy. The moving of Moroccans into the western Sahara since 1974, and constantly putting off the day of an independence referendum for that region as the population changes in a more congenial direction, might be seen as an example of the second. Faced with these sorts of possibilities, we might be moved to favour ‘high hurdle’ theories of secession instead (Beiner, 2003), such as the remedial approach.

However, the issue might look different when viewed through the lens of liberal nationalism. If we take a broadly positive view of nationalist movements that are largely democratic and respectful of minorities, then the more permissive democratic approach may be more appealing. Again, there are important lessons here about the relationship between political theory and political practice. Even in cases where theories come across as abstract and general, assumptions about the real political world can and will influence our approaches.

There are no easy answers to the adequacy of secession and referendums as tools for the satisfaction of claims to national self-determination. Each case will throw up unique features; political theory cannot simply provide a universal blueprint for dealing with such specific claims. Having said that, perhaps it is the case that ‘democracy’ is not just a matter of votes, for instance in secession referendums. It has been suggested that we may be able to take all the concerns about multiple claims for self-determination – illiberal nationalism, the domino effect, political instability and so on – and incorporate them into a wider approach to ‘democratic management’ of these issues: ‘the project of democratic management must protect minorities, resist majority tyranny, correct the misuse of majority rule, and achieve a workable balance between majority rule and minority rights’ (Baogang He, 2002, p. 93).

We noted in passing that some observers worry about permissive approaches to national self-determination and secession, on the grounds that we would end up with a patchwork of too many small states. Critics are concerned about the potential destabilising effects of a secessionist free-for-all. Many larger states today are not in fact national states, but rather multinational states. Encouraging national self-determination in a strong and literal way might threaten the integrity of all but a handful of the world's existing states:

Is it theoretically coherent to try to apply the self-determination principle to all multinational or multiethnic states? … Carried to the logical limit, the theoretical consequences are somewhat catastrophic; for hardly any states today would be immune from having their legitimacy normatively subverted.

(Beiner, 1999, p. 5)

In a similar vein, Ernest Gellner once wrote that we live in a world that ‘has only space for something of the order of 200 or 300 national states’ (quoted in Beiner, 1999, p. 5). Leaving aside the fact that a world of 300 states would be enormously different from one with the almost 200 states of today, there is a case for replying to this by pointing out that size is quite arbitrary when it comes to nation-states. This issue much exercised the great democratic theorists around the time of the American and French Revolutions. Putting it simply, the terms of the debate can be seen as being set by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the famous Swiss-French political theorist and an inspiration for the French Revolution, who felt that liberty was threatened whenever a political unit grew beyond the size of a city-state; and James Madison, American revolutionary and the fourth president of the USA, who saw the extension of the political unit to continental proportions as a positive barrier to factional domination of a political system.

There are two basic ways in which we can understand the question of the appropriate size of political units. The first is to interpret it as a question about the appropriate extent of a unit's geographical area. The second is to see it as a question about the size of the population of the unit. Geographical size is, arguably, less significant now than before the communications revolution. Peripheral regions of a large political unit need not be out of touch with activities at the centre. Political participation, especially in elections, is not unduly hampered by distances. The question of population size may be more important. Robert A. Dahl suggests that the ‘smaller is better’ argument looks ridiculous if pushed to extremes: ‘If it were true that a smaller system must always be more democratic than a larger, then the most democratic system would consist of one person, which would be absurd’ (Dahl, 1989, p. 205). But there is little need to jump to such extremes. A further objection to the argument that smaller is better is Dahl's view that larger units allow for citizens to have some say in more matters. In other words, the scope of policy in larger units is greater; citizens can participate in the resolution of more issues than they could in smaller units. This may be true, but those ‘extra’ things one might be able to influence may not be matters which citizens are generally concerned about.

Further, the objects of citizen concern can be as much the product of the very existence of the larger unit. For example, the USA being a larger unit means that citizens can have some (highly indirect and minimal) say in nuclear weapons policies, clearly a matter of global importance. However, it is arguably the existence of political units of such continental dimensions which has generated the resources to devote to such weapons in the first place. Smaller units may restrict citizens’ say to smaller, more local matters, but in a world of smaller units the global questions may not loom so large anyway; these small, local matters would no longer seem, or even be, small or merely local.

Summary

The issue of secession has proved to be a challenge to political theory, and shows how practice impinges on theory.

A series of referendums, or ‘remedial right’, are two prominent approaches to secession.

Attitudes to nationalism are influenced by whether a given example is seen as ‘liberal’ or ‘illiberal’.

The question of the appropriate size of political units is part of debates on nationalism.

7 Conclusion

We have explored nations, national self-determination and secession as living political ideas. Perhaps the key points to emerge from the discussion are that:

the nation-state is the basic political community in the contemporary world, despite regional and global challenges;

subjective approaches to defining nations, prioritising awareness of belonging to a national group, have advantages over efforts to construct objective definitions;

the symbolic, imagined, aspects of nations can be as important as historical or other cultural ‘facts’ about the nation;

nationalism is a many-sided and potent political ideology, though we can pinpoint some general characteristics shared by all nationalist movements;

political theorists have offered imaginative responses to dilemmas of secession and national self-determination, such as the democratic and remedial approaches;

all theoretical ‘solutions’ to issues of secession are vulnerable to objections;

our assessments of political theories can depend on (sometimes unspoken) assumptions that we make about political realities and specific cases.

References

Acknowledgements

This free course is an adapted extract from the course DD203 Power, dissent, equality, which is currently out of presentation

This chapter is taken from Living Political Ideas (eds) Geoff Andrews and Micheal Saward published in association with Edinburgh University Press (2005) as part of a series of books which forms part of the course DD203 Power, Dissent, Equality: Understanding Contemporary Politics.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence

The third party material below is credited to the following rightsholders and sources:

Course image: Chris in Flickr made available under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Licence.

Figure 1 © SIPA Press/Rex Features;

Figure 2 © Empics Ltd;

Figure 3 (left) © Israel Infotour; (right): © Jan de Jong

Figure 4 © Jan de Jong;

Figure 5 © Rafiqur Rahman/Reuters;

Figure 6 Centre for the Study of Cartoons and Caricature, University of Kent. © News International Syndication.

Adapted from Figure 2 © Empics Ltd;

Don't miss out:

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University - www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses

Copyright © 2016 The Open University