Who counts as a refugee?

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 20 April 2024, 12:59 AM

Who counts as a refugee?

Introduction

This course explores the dynamic interrelationships between citizenship, personal lives and social policy for people who have fled their country of origin seeking asylum in the UK.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of Level 3 study in Social sciences

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

understand changing constructions of ‘refugees’ and ‘asylum seekers’ over the last century

Identify ways in which the study of refugees and asylum seekers raises profound questions about the basis and legitimacy of claims for ‘citizenship’

understand how the personal lives of refugees and asylum seekers have been shaped by social policy that constructs them as ‘other’

understand how refugees and asylum seekers have negotiated and resisted these effects and themselves shaped social policy

understand how ‘knowledge’ about refugees and asylum seekers is produced and reproduced through research.

1 The aspects and meanings of citizenship

The issues discussed in this course are considered in relation to different aspects and meanings of citizenship: people's legal and political status, their rights, opportunities to work, access to welfare, sense of identity and belonging, and practices of the everyday.

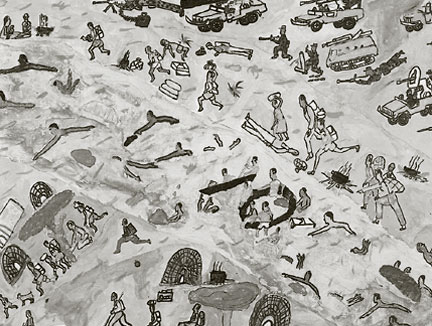

Throughout human history people have migrated from their place of birth for different reasons – for example, to seek new ways of surviving, to colonise new lands, to establish new markets for trade, or because they feared for their lives in their country of origin. Large movements of refugees around the world, as in the late twentieth century, are often linked to wider regional or global struggles, as illustrated in Figure 1. People flee mainly because of war, repression and human rights abuses rather than poverty (Crawley and Loughna, 2003). However, the distinction between being a ‘refugee’ or an ‘economic migrant’ is neither simple nor straightforward.

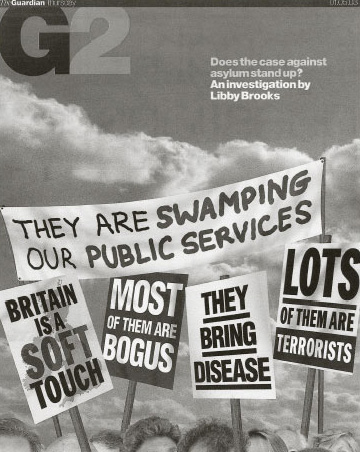

To explore some of the reasons why people have sought refuge in the UK in particular, we are using the personal stories of four individuals, placing the interpretation of these accounts in the social policy context of two particular historical moments – the decade following 1933 and the period between 1991 and 2003. During this latter period ‘asylum’ was constructed by successive UK governments as a ‘political crisis’ in the context of a ‘crisis’ of the UK welfare state, a drive towards a common European asylum policy (Bloch and Schuster, 2002) and a claim that the forces of globalisation are irresistible. Dominant official and media discourses assumed that increasing numbers of people were seeking asylum in the UK because of the generous welfare benefits available, that the ‘welfare state’ could not afford this, that the UK was already overcrowded, that there were not enough jobs and that the presence of so many ‘aliens’ or foreigners was a threat to ‘community’, ‘national identity’ and ‘our’ way of life. Figure 2 shows some typical headlines from UK newspapers in the early 2000s, in which ‘asylum seekers’ are clearly constituted as one of the most demonised groups of people in the UK media.

The sets of interconnections between citizenship, personal lives and social policy can be thought about in the following way.

First, refugee and asylum policy and practice raise important questions about the nature of citizenship in relation to the rights and sense of belonging that citizenship as a status conveys. For example:

-

Should citizenship be based upon place of birth, parental nationality, place of residence, or simply human value and dignity, regardless of these issues?

-

Should globalisation mean that rights of citizenship can no longer simply be tied to birth in a specific nation-state?

Second, the mutual constitution of personal lives and social policy comes into stark focus for the person who flees one country and has to negotiate entry to a life in a new country (each of the countries having its own particular social, economic, political and cultural forms). The personal accounts that follow in Section 2 illustrate these connections well.

Third, exploring these interconnections illuminates the relationship between citizenship as a set of rights and claims, on the one hand, and as cultural or national identity on the other.

The primary theoretical perspective through which these issues are explored in this course is post-structuralism, because of its emphasis on the production of social meaning and the effects of such meaning or ‘knowledges’ on the experiences of different social constituencies. Post-structuralism is also used because this emphasis on meaning systems – or discourses – allows us to think about alternative or counter discourses through which opposition to dominant policy discourses may be presented. Forms of feminist and postcolonial theory will also be drawn on. Feminism alerts us to the impact of gender on the experiences of refugees and asylum seekers and how discourses of gender run through relevant policy. Postcolonial theory draws attention to questions of ‘nation’, its peopling, and national identity in colonial and neo-colonial configurations of power. It helps us to consider links between contemporary government approaches to refugees and asylum seekers and the generalised anxieties over multiculturalism and cultural identity prevailing in the UK in the early twenty-first century. The nature of the evidence used in our explorations is a theme running through the rest of the course.

2 Personal lives

We start our exploration of the interrelationship of personal lives and social policy with personal stories.

Activity 1

Read Extracts 1, 2 and 3 below, and make notes on areas of similarity and difference. What questions are raised about the relationship between personal lives and social policy?

Extract 1: Lotte and Wolja, 1938

On September 1st 1938, Lotte arrived at Harwich in England to join Wolja, the man she was going to marry. They had known each other for two years in Germany, and wanted to make their lives together, knowing that, as Jews, this would have to be outside Germany, the land of their birth and their identity. They both came from non-observant Jewish families, but since 1933, when Hitler came to power in Germany, they had gradually, but systematically, lost rights and opportunities to work.

In 1932, aged 19, Lotte had entered Berlin University to study medicine, but she was expelled in 1934. Wolja had completed his education, including in 1935 his PhD in Mathematics and Physics, but as a Jew he was unable to obtain work; he lived with his parents on their savings. Although born in Berlin, his father came from Romania and his mother from Poland. He grew up with Romanian citizenship, was naturalized as a German citizen in 1932, but lost this citizenship again in 1935, under new laws designed to preserve the ‘purity’ of the German ‘race’.

Lotte and Wolja knew that their lives could also be threatened in the future. Making a decision to leave was one thing; finding a way of doing it was another. At the time that they met, Lotte was living with her widowed mother in Berlin, planning to join her older sister and husband in Palestine. Meeting and falling in love with Wolja changed these plans. As a stateless person, with little money and poor eyesight, he had difficulty finding a place of refuge. For Switzerland he needed to fit a quota based on ‘nationality’; the USA refused him a visa because of his poor eyesight, despite his finding affluent relatives to ‘vouch’ for him. Eventually in May 1938 Wolja was granted permission to enter the UK ‘to seek work’, following the decision of the British government to grant visas to ‘desirable’ immigrants such as qualified scientists.

For four months Lotte made arrangements for her own departure to England, organizing her mother's journey to Palestine, and packing and shipping as much of their joint possessions as she could. As a woman, she could seek to enter the UK on a ‘domestic permit’, her only option as she lacked professional qualifications. So she had to wait for Wolja to find a family in England who would take her. The letters between them during this time reveal many of their feelings. He was extremely anxious and lonely in England. Although he had some friends (other German Jewish refugees), they tended to be in couples, already married. He relied on these friends and on Jewish refugee organizations for financial support. Despite his scientific qualifications, and his feeling of how much he could offer to the UK professionally, it was difficult to find work. He was registered in the UK as an ‘alien’, with temporary permission to stay. He did not know whether he would still be here when Lotte arrived, or more generally what would become of them both. Her letters express anxiety about having to do domestic work. She writes: ‘I have never enjoyed housework, it is not in my nature; please try to find me somewhere to work with children’. Both had learned English in school; they thought they would be safe in England, and could probably find work; if not they would try America again. They married in July 1939, just before the outbreak of World War II. He fought a 5 year battle with the Home Office to be recognized as stateless, rather than German, and was naturalized as a British citizen in 1947.

Extract 2: Victor, 1987

The following [paragraphs] recount my seven-year battle with the British government to obtain political asylum, the destructive force this process has on human dignity and human rights, and the ultimate journey into exile …

… In September 1984, the Air New Zealand jumbo jet on which I was travelling landed at Gatwick Airport. Shortly afterwards, I stepped out of the business-class seat (courtesy of Reuters News Agency) into a cold and wintery England, leaving behind the warmth of my native Fiji. The cold of England was, however, warmed with English hospitality …

… As I got into the car for Oxford University, it finally dawned on me that I was now in England, a country which had not only existed in my history and geography school books but had dominated every aspect of my life in Fiji … Now, I felt as if the Empire's stepchild had come ‘home’, even though I had only arrived to study on a Reuter's fellowship at Oxford.

Although Fiji had shrugged off British colonial rule in 1970, … The Queen remained the constitutional head of Fiji … and Her Majesty continued to stare in our faces from the coins and notes in circulation in post-independent Fiji …

[But] … democracy died in Fiji on 14 May 1987 and with it, my hopes of returning home.

It was also the beginning of a long and seemingly endless struggle to secure refuge in my ‘imagined home’ in England, and to join a long line of political dissidents in exile …

But who would provide refuge to me? The most obvious and immediate host was Her Majesty's Government in Great Britain. From my childhood … I was taught to sing ‘God Save Our Gracious Queen’. Now I was singing to Her Majesty's British Government, ‘Save Me From the Dictators in Fiji’. Were they going to respond to my call? Was there protection under the Union Jack (also fluttering in the left-hand corner of the Fiji flag) from the winds of Fijian racism? Was I going to be reluctantly transformed from Reporter to Refugee?

…

The ordeal of waiting for a decision for asylum is a long, arduous, and painfully frustrating experience. Indeed, the British Home Office took three long years to relay its initial decision. On 8 August 1990, it notified me that the application for refugee status had been carefully considered but refused. No reasons were furnished. However, I was granted exceptional leave to remain (ELR) in the United Kingdom until 8 August 1991 … because of ‘the particular circumstances of the case’ …

… The advantages of full refugee status, as opposed to exceptional leave, are not very great, but I wished to appeal nonetheless …

Seven years after I made my original claim, I was finally granted Refugee Status under the United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees …

Extract 3: Françoise, 2001

Françoise, a 21-year-old from Cameroon, arrived in the UK in June 2001. She spent most of her pregnancy in detention. When we met, she and her baby had been locked up for five of his six months. Françoise was either sold or given away when she was four years old, and brought up in a Muslim farming family. When she was 17, she was told that she would become one of her foster father's wives. When she refused, she was locked up and beaten. She ran away.

On arrival in Britain, she was held at Oakington detention centre, where asylum seekers are fast-tracked through the process by in-house lawyers. Her asylum plea was rejected and she was dispersed to Leeds, pending an appeal. Soon after arriving, she discovered that she was pregnant. When Françoise got to the Leeds address given to her by the Home Office National Asylum Support Service (Nass), she was told that there was no room and so was sent on elsewhere. Her lawyer at the time told her that she didn't need to inform Nass because he had her details and would keep in touch.

Her baby was born prematurely, at 34 weeks. She spent three weeks in hospital in Leeds, then went back to the flat she'd been allocated. A week later, ‘They came for me at 7am. They said, “Your case is over, you are going into detention.” They started to put my things into bags. I could not even tell the health visitor that we were going.’

Unfortunately, her asylum paperwork had not kept up with her and notification of her appeal hearing had been sent to the wrong address. It was rejected without her having a chance to speak for herself. ‘She fell into the gap that many dispersed and bewildered asylum seekers experience,’ says her current lawyer, Eileen Bye.

In Françoise's absence, her case was turned down and she was detained pending removal. It doesn't seem to have mattered that she knew nothing of the hearing, let alone that she had a month-old premature baby. ‘How can they remove me when they have not heard my case?’ she asks. ‘What will happen to him if I go back? I have no money, no family.’

Discussion

Although we have only had glimpses of Lotte's and Wolja's, Victor's and Françoise's stories, we can imagine the deep emotional pain of the series of losses they experienced in either being forced to leave, or being unable to return to, their home, family, friends and the familiarity of everyday life. Undoubtedly their pain was exacerbated by the uncertainty of their status in the UK.

We can pick out some similarities and differences in their stories:

-

Lotte, Wolja and Françoise were all young, in their twenties;

-

All four people fled, or in Victor's case did not return to, their country of origin because they feared for their lives.

-

For Lotte, Wolja and Victor it was not easy to find a place of refuge; they came to, or stayed in, the UK because it offered safety, rather than choosing it specifically as a destination. Even Victor, for whom the UK was already his ‘imagined home’, did not envisage staying permanently.

-

These four people fled at different historical times, came from very different parts of the world and experienced very different kinds of persecution. Lotte and Wolja, persecuted as ‘Jews’, came from Europe; Victor could not return home to Fiji because of his political activities; and Françoise fled from Cameroon because of persecution within her family.

-

Lotte, Wolja and Victor were all well educated. Wolja had a PhD, and Victor was a reporter who had gained a Reuter's fellowship to study at Oxford University; Lotte's education had been interrupted.

-

Gender played a key part in these stories. Whereas Wolja could come to the UK to ‘seek work’, Lotte could only come on a ‘domestic permit’, although this was not her choice of work. Françoise's experiences, the reasons for her flight and her time in detention were structured through her gender and the domestic practices of gender in her place of origin.

-

The language and terminology have changed. Lotte and Wolja were subject to controls as ‘aliens’. In the 1990s, policies referred to ‘asylum seekers’ and ‘refugees’, with a crucial distinction being made between these two categories of people.

Flight

He was carrying only

His papers,

His caution,

A friend's farewell,

A suitcase too small to be seen,

And his misgivings of what the road might conceal.

These four personal stories come from very different sources. The story of Lotte and Wolja is constructed from their children's memories of stories they had told, together with information in letters and documents found after their deaths. Victor wrote his own story in order ‘to sketch in the human dimension of the ordeal (and the peril) in applying for political asylum in Great Britain’ (Lal, 1997, p. 62). Françoise's story is taken from an article in The Guardian newspaper in 2002. Although their lives were shaped by social policy, they did not simply accept its effects. They all experienced themselves as people with needs and rights that they would pursue. We return to these stories many times, both to explore further this relationship between personal lives and social policy, and to consider what kind of ‘knowledge’ or evidence such stories constitute.

3 Social policy and citizenship

Immigration law and policy do not traditionally appear under the heading of ‘social policy’. We argue here for a broader definition that includes these, since the laws, policies and procedures concerned with the rights of people to enter the UK and to claim refuge can have a profound effect on personal lives, as our personal stories have already shown.

Immigration and asylum is a rapidly changing area of social policy. Four major pieces of legislation were enacted between 1993 and 2002. Asylum seekers have been controlled and monitored as much through the guidance and rules issued to relevant agencies and bureaucrats who implement the legislation as through primary legislation. Table 1 lists some of the important developments since the beginning of the twentieth century. We shall not explore these in detail – this is a resource to refer to throughout the course.

| 1905 | Aliens Act |

| Targeted ‘undesirable aliens’; asylum seekers exempted | |

| 1914 and 1919 | Aliens Restriction Act and Aliens Act |

| Controlled the activities of aliens | |

| 1920 and 1925 | Aliens Orders |

| Included removal and restriction of entry of black seamen | |

| 1948 | Universal Declaration of Human Rights |

| Includes the right to seek and enjoy asylum in other countries | |

| 1951 | United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees |

| A refugee is someone who: | |

| – has a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion | |

| – is outside the country they belong to or normally reside in | |

| – is unable or unwilling to return home for fear of persecution | |

| Limited to those who became refugees as a result of events occurring before 1951, and, by many states, to events in Europe | |

| 1962 | Commonwealth Immigration Act |

| Introduced work voucher scheme for Commonwealth immigrants | |

| 1967 | UN Protocol |

| Extended the 1951 UN Refugee Convention to cover any person, anywhere in the world at any time | |

| 1971 | Immigration Act |

| Gave immigration officers powers to detain asylum applicants | |

| 1987 | Carriers’ Liability Act |

| Introduced fines on airlines and shipping companies for carrying undocumented passengers | |

| 1990 | Dublin Convention |

| European Union (EU) countries given the option to remove applicants who have travelled via another ‘safe’ EU country back to that country | |

| 1993 | Immigration and Asylum Appeals Act |

| First piece of legislation introduced into British law targeted at asylum seekers: | |

| – fingerprinting introduced | |

| – practice of returning asylum seekers to ‘safe’ third country | |

| – rights to social housing reduced | |

| – 48-hour limit on appeal after a negative decision | |

| – carrier's liability extended | |

| 1996 | Asylum and Immigration Act |

| – benefit entitlement withdrawn from ‘in-country’ asylum applicants (successfully challenged in the courts) | |

| – internal ‘policing’ – fines for employers taking on anyone without appropriate documentation | |

| – complete differentiation between ‘asylum seekers’, refugees and those with ‘exceptional leave to remain’ in relation to housing and housing benefits | |

| – local authorities had statutory duty to provide for destitute single asylum seekers under 1948 National Assistance Act; families supported under 1989 Children Act | |

| 1999 | Immigration and Asylum Act |

| – asylum seekers removed from mainstream welfare benefits system; entitled to £10 cash and vouchers redeemable at specific supermarkets – worth in total 70 per cent of basic income support – if they can prove they have no other means of support | |

| – National Asylum Support Service (NASS) now responsible for their welfare | |

| – introduction of pre-entry controls – Airline Liaison Officers at airports in ‘asylum producing countries’ [sic] introduced or reinforced | |

| – carrier's liability extended to include trucking companies | |

| – NASS provides accommodation for anyone recognized as destitute | |

| – dispersal policy: accommodation only offered outside London and the south-east; no choice over destination | |

| – no welfare provision for those granted refugee status | |

| 2002 | Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act |

| – replacement of vouchers by a cash voucher system | |

| – end to the presumption that all destitute asylum seekers should receive support from NASS; eligibility restricted to those who have applied for asylum ‘as soon as reasonably practicable’ after arrival in the UK | |

| – power to remove subsistence-only support option | |

| – applications from ‘white list’ of ‘safe countries’ assumed to be ‘clearly unfounded’, with no right of appeal; Home Secretary can add more countries as he or she sees fit | |

| – asylum seekers no longer able to work or undertake vocational training, until given a positive decision, however long that takes | |

| – greater powers to tackle illegal working | |

| – development of accommodation centres with full board and education for children | |

| Citizenship and nationality: | |

| – requirement to pass English language test (older people and disabled people exempt) | |

| – citizenship ceremony involving an oath of allegiance | |

| – power to remove British nationality if a British citizen has done anything ‘seriously prejudicial to the vital interests of the UK’ | |

| – the right for children to be registered as British citizens | |

| 2003 | Asylum and Immigration (Treatment of Claimants etc.) Bill |

| Seen by the Home Secretary as the third phase of reforms to the asylum and immigration system, following the 1999 and 2002 Acts. Received its Second Reading in the House of Lords on 15 March 2004. Proposals include: | |

| – penalties for arriving in the UK without documentation | |

| – withdrawal of support from families who have unsuccessfully reached the end of the asylum process | |

| – restricting asylum seekers’ access to asylum appeals | |

| – increasing the Home Secretary's powers to remove asylum seekers to a ‘safe third country’ without fully considering their asylum application |

4 Refugees, asylum seekers and citizenship

4.1 The context and significance of the historical moments under consideration

The two historical moments we are considering were not chosen arbitrarily; they are both significant times in the overall history of people seeking asylum in the UK. Some important relationships between them give us a starting point for looking at continuities and discontinuities in both policy and experience.

Firstly, Lotte and Wolja were admitted to the UK under the 1905 Aliens Act. This was the first fully implemented legal attempt to control the entry of ‘foreigners’ into the UK. It aimed to keep out all ‘undesirable aliens’, while exempting those seeking asylum or refuge. After the First World War came increasing possibilities for states to control their borders, including the introduction of passports. However, refugees were still seen as unwilling migrants, rather than people seeking a better life in a rich country.

During the late 1980s and 1990s, as issues around ‘asylum seekers’ came to prominence in the public agenda, the dominant historical ‘memory’ was that Jewish refugees were welcomed to the UK in the 1930s as ‘genuine’ refugees and model immigrants, who made no demands upon the welfare system, were willing to ‘assimilate’, and made great contributions to the social and cultural life of the UK. Historical research shows, however, that the reality of their experience was very different. The UK government was very reluctant to admit refugees from Nazism in the 1930s and many were deported (see Figure 3). It did not want permanent settlers in a country considered to be overcrowded and which had mass unemployment. Jewish refugees were admitted temporarily only when the English Jewish community assumed all the costs of receiving and supporting them (London, 2000). We will consider later the implications of this deal for understanding ‘citizenship’.

These two historical moments are connected in a second way. The United Nations (UN), formed out of the aftermath of the Second World War and in the context of the beginning of the Cold War, published the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 and the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees in 1951. The Convention developed out of the very specific experiences of the Holocaust and the 60 million people displaced from their homes by the Second World War. The UK was one of the first signatories to the Convention, but no clear procedures were put in place for guaranteeing refugees’ rights. Rather, as Bloch and Schuster (2002, p. 397) argue, ‘refugees and asylum seekers alike were “looked after” … because it was politically expedient to respond humanely to those fleeing, mostly from the Soviet Bloc or its allies. They “deserved” compassion and, by extension, access to welfare because of what they had “endured”’. Indeed, the term ‘asylum seeker’ was first used to refer to political dissidents from the Soviet Union.

Crucially, the Convention created a formal definition of a ‘refugee’, although, until 1967, this applied only to people fleeing from European countries (see Table 1). In the early 1990s, the break-up of the Soviet Union and the increase in political turmoil worldwide resulted in the closing of doors for migrants into Western Europe at a time when the EU was allowing its citizens free movement within member states. Since the rights of refugees were governed by international rather than national laws, ‘asylum’ became the only legal route for entering most Western European countries. Concern about the ‘crises’ of numbers and the costs to the welfare state resulted in moves to tighten up the interpretation of who qualifies as a ‘refugee’. However, it is important to put the European and UK ‘crises’ into context. In 2002, ‘developing countries’ provided asylum to 72 per cent of the world's refugees. Within the EU: ‘The UK received the highest number of asylum applications … but ranked fifth when population size was taken into account’ (Shaw and Durkin, 2003, p. 7). In the early twenty-first century, paradoxically, both those campaigning for the rights of refugees and asylum seekers and those wishing to limit them (including the UK Government) agree that the Convention no longer speaks to the current global situation.

The plethora of legislation and social policy since the early 1990s is widely understood as successive attempts to ‘stem the flow’ of refugees. They include:

-

the development of ever tighter controls on ways of entering the country;

-

the creation of disincentives for people to come to the UK, through restricting their access to welfare;

-

increasingly, in the early twenty-first century, detention and ‘criminalization’ of those seeking asylum or refugee status who are in the UK;

-

deportation of those seeking asylum whose claims are ‘unsuccessful’.

Despite these dominant views in the 1930s and today, a series of tensions and contradictions within government policies can be identified. A continuity of approach can be seen as successive UK governments, both pre- and post-1951 and continuing into the twenty-first century, have wished to be seen to be carrying out their international obligations to refugees, and to maintain the picture of the UK as a ‘safe haven’, which welcomes refugees and recognises their contribution to economic, social and cultural life. The 1951 UN Convention provided a clearer definition of who counts as a refugee. A significant change in the approach took place from the 1990s with a splitting of the category ‘refugee’ into two distinct groups – ‘asylum seekers’ and ‘refugees’ – as a result of the belief that the majority of people seeking asylum were not ‘genuine refugees’ in the terms of the 1951 Convention. Since the early 1990s, therefore, everyone seeking asylum on the basis of their claim to be a refugee, is called an ‘asylum seeker’ within law and social policy. ‘Refugees’ are those whose claims have been recognised; they are entitled to the same social and economic rights as UK citizens. Although not legally citizens, they have full access to medical treatment, education, housing and employment. We can see how the state organises a connection between personal lives and social policy through identification of the categories that link people to welfare, in this instance through the different statuses accorded people within the procedures of the asylum process.

In developing tight controls and regulations, governments have claimed to recognise the fears of many of their citizens about spiralling costs of welfare services and benefits, and the threat to the ‘British way of life’ that asylum seekers are assumed to pose. Indeed, being able to welcome ‘genuine refugees’ is said to be dependent upon controlling and penalising the majority of asylum seekers who are in fact ‘bogus’. In this way, a long-standing tenet of UK policy – that ‘good race relations’ depend upon strong and fair immigration controls – is reinforced (Lewis, 1998).

Counter voices have also helped to shape social policy and personal lives. These have included asylum seekers and refugees themselves, historians of the 1930s and a range of UK community and voluntary organisations. These latter organisations have often been called upon to provide material and psychological support to asylum seekers and refugees. They have been in the forefront of campaigns first to challenge the regulations and legislation, and their administration, and second to ‘nail the myths’ about refugees and asylum seekers presented in much of the media.

4.2 Feminist perspectives: who counts as a refugee?

The UN Convention has a very narrow definition of a ‘refugee’, which does not ‘accommodate those people who are forced to leave their country of origin because of economic and/or social disruption caused by environmental, political or economic turmoil or war. These are precisely the reasons that propel most refugees from the underdeveloped South’ (Lewis, 2003, p. 327). If we examine this definition further through a feminist theoretical perspective, we can see how social policy operating at a national or international level makes assumptions that create the boundaries of a gendered personal.

Activity 2

Look again at Extracts 1 to 3 in Section 2.

-

In what ways were the experiences of the four people structured through gender?

-

To what extent did class also play a role?

Discussion

Both gender and class helped to construct the experiences of the people concerned. Wolja was allowed to enter the UK to seek work, but only because he was professionally qualified and had ‘cultural capital’ to bring with him. Lotte was persecuted as a ‘Jew’, not as a woman; but, as a woman, a ‘domestic permit’ offered her the (only) way out of Nazi Germany. By contrast, Françoise was persecuted within her family because she was a woman.

It is easier to recognise the ways in which Lotte's and Françoise's experiences were constructed in part through gender, because Wolja's and Victor's experiences are normalised. That is, their experiences as male refugees are taken as the norm for all refugees. The ways in which women and men live their lives in relation to one another are so taken for granted in everyday practices, that it is harder to see that male experiences are gendered. Similarly, we find implicit gender assumptions within social policies and practices which have contradictory implications for both women and men. On the one hand, in both historical moments men have been viewed as the principal asylum applicant in applications from couples and/or families. In addition, in the late twentieth century ‘permission to work’, when granted, was usually only given to the (male) principal applicant. This dependence on their husbands is problematic for women, who may lose all their rights if the marriage ends. Women on the receiving end of domestic violence are particularly vulnerable. On the other hand, there is evidence that men have more to lose than women in terms of status, and are less able to adjust emotionally to a changed status, particularly if they are unable to work and act as a ‘breadwinner’. Indeed, for some women, becoming a refugee may be the first time they experience an independent status and an opportunity of new roles within the community (Sales, 2002).

The concept of domestic service, which offered Lotte her escape route, is itself one constructed through both class and gender. The UK was the only country offering a ‘specific scheme of rescue for the Jews through domestic service’ (Kushner, 1994, p. 112). Many of the women refugees were recognised not to be of ‘the domestic class’ by the Home Office, which accepted that such women would probably want to take up another occupation. However, by keeping them in domestic service for a few years the ‘“large unsatisfied demand” for servants in Britain’ could be satisfied (Kushner, 1994, p. 97; Holden, 2004). Kushner suggests that:

the predomination of class factors in Britain worked to the overall advantage of those trying to escape from Nazism. The desire to maintain the lifestyle associated with the employment of servants, as well as a genuine determination to help the Jews, enabled a scheme of rescue without parallel to be implemented at that time. The 20,000 Jewish women were treated in a variety of ways, including the extremes of sympathy and naked exploitation.

(Kushner, 1994, p. 114)

More generally, it has been argued that: ‘The 1951 UN Convention … and the 1967 Protocol … [have been] interpreted through a framework of male experiences during the process of asylum determination in the UK’ (Refugee Women's Legal Group, 1998, p. 1), thus denying women effective protection under international law. Women and children constitute the majority of the world's refugees, albeit as a minority of the asylum seekers in Europe (Kofman and Sales, 2001). However, the original Convention does not include the kind of ‘gender-specific’ persecution that Françoise experienced. Women have to claim that their persecution as women resulted from their membership of a recognised social group. Canada, the USA and Australia have all produced gender guidelines which recognise these difficulties, but no agreed gender guidelines exist within the EU, even though the European Parliament called in 1985 for women to be recognised as a ‘social group’ in the terms of the Convention (Kofman and Sales, 2001).

The Refugee Women's Legal Group argues that:

women suffer the same deprivation and harm that is common to all refugees … [but] The experiences of women in their country of origin often differ significantly from those of men because women's political protest, activism and resistance may manifest itself in different ways. For example:

Women may hide people, pass messages or provide community services, food, clothing and medical care;

…

Women who do not conform to the moral or ethical standards imposed on them may suffer cruel or inhuman treatment;

Women may be targeted because they are particularly vulnerable …

… [or] persecuted by members of their family and/or community.

(Refugee Women's Legal Group, 1998, p. 1)

Similar difficulties in having their claims for asylum recognised under international law face women and men who are persecuted on the ground of their sexuality as lesbians or gay men, and transgender people (Saiz, 2002).

5 Citizenship, identity and belonging

5.1 Post-structuralist perspectives: the production of social meaning

With the onset of the Second World War, because they came from Germany, Wolja and Lotte became ‘enemy aliens’ overnight, an identification they resisted. By contrast, both Victor and Françoise were viewed as ‘asylum seekers’. In all cases, their status derived from their country of origin. The discussion of gender and sexuality in Section 4 reveals a tension around the idea of citizenship as a status reflecting ‘human rights’ rather than rights that flow from membership of a nation. In Section 5, we will explore further such contested ideas about citizenship by considering how post-structuralist and postcolonial theoretical perspectives help us to think about the relationships between citizenship, identity and belonging.

A post-structuralist theoretical perspective focuses our attention on ways in which social meanings are produced, and the consequences of those meanings in this instance for refugees and asylum seekers. It also alerts us to look for alternative or counter discourses.

Activity 3

Table 2 includes a list of terms used in discussions of migration.

| Alien | Used in earliest legislation (1828, 1838 and 1905) to describe those ‘outside’ the nation |

| Refugee | Someone forced to flee their country of origin because of war, famine or persecution |

| Convention refugee | Someone whose circumstances meet the criteria of the 1951 UN Refugee Convention |

| Asylum seeker | Used since the 1990s for people seeking refugee status, whose claim has not yet been recognised |

| Forced migrant | Used to describe all those forced to flee, for whatever reason and whatever their legal status |

| Displaced person | Someone who has fled from their home, but remains within the same national territory |

| Exile | The condition of being forced to live away from one's ‘home’ |

| Exceptional leave to remain (ELR) | Until April 2003, a status granted to people whose claim for refugee status was not recognised, but who were allowed to stay in the UK on humanitarian grounds |

| Humanitarian protection | Replaced ELR on 1 April 2003 |

| Immigrant | Someone who has moved to live in another country, whether as a refugee, or to seek work, for family, emotional or any other reasons |

| Economic migrant | Someone who migrates to seek work |

| Agent | Someone who helps an asylum seeker to get into another country, for a financial payment |

| Trafficker | Someone who exploits an asylum seeker, for continued financial gain – for example, by forcing them into prostitution or illegal work |

-

Do the definitions provided reflect the social meanings that are produced when these terms are used in the media and social policy?

-

How might people identified through these terms resist such meanings?

Discussion

-

Although some of these words signify particular legal statuses and rights, they are also discursive categories; that is, they carry meanings that help to locate people in a symbolic chain of associations in which they are categorised as more or less deserving. They may also help to construct people's sense of identity and belonging.

-

In public, media and political discussion, the very words ‘refugee’ and ‘asylum seeker’ carry silent adjectives with them – ‘genuine’ and ‘bogus’.

-

Most asylum seekers are assumed to be ‘economic migrants’, used in the media as a term of abuse for people who have tried to use the asylum procedures to seek a better life, even though many of them have left places ravaged by war or famine.

-

Categorising very diverse peoples as ‘asylum seekers’ or ‘refugees’ focuses on their common experiences of suffering and exile, while ignoring the impact of other social divisions in their lives. This can homogenise them and reinforce stereotypes.

We saw from our personal stories that there are huge differences in people's experiences, and in the meanings of those experiences. Moreover, although personal lives reflect the bigger societal picture of power, inequality and difference, there is always an ‘excess’. That is, individuals can also resist these identifications and see themselves, for example, as people with basic human rights.

Both social policy and the media play a role in the construction of discourses of refugees and asylum seekers as ‘other’ and often use terms such as ‘asylum seeker’, ‘refugee’ and ‘immigrant’ interchangeably: ‘In its report … of William Hague's speech on asylum policy, the Times referred to “asylum seekers” in its first paragraph; “immigrants” in its second; and “refugees” in its third’ (Moss, 2001, p. 48, original emphasis). Moss describes this ‘confusion over the language’ as reflecting ‘our confusion over the issue itself’. However, a post-structural perspective suggests that such use of language reflects not confusion but important meanings which set up chains of connections. For example, such interchangeable use of terms strengthens the association between asylum seekers and ‘undesirable’ or ‘illegal’ immigrants.

Refugee

So I have a new name – refugee

Strange that a name should take away from me

My past, my personality and hope

Strange refuge this.

So many seem to share this name – refugee

Yet we share so many differences.

I find no comfort in my new name

I long to share my past, restore my pride,

To show, I too, in time, will offer more

Than I have borrowed.

For now the comfort that I seek

Resides in the old yet new name

I would choose – friend.

This ‘war of words’ is important because ‘beyond simple terminology, words constitute the strategic weapons taken up by politicians, association activists, social workers and intellectuals, who give them a new content according to actions and reactions’ (Kastoryano, 2002, p. 15). Thus supporters of the rights of asylum seekers and refugees often use the term ‘refugee’ much more widely than its narrow legal definition. In the library of The Guardian newspaper:

Everyone gets put into a file called ‘refugees’, with the exception of high-profile individuals in well publicised cases who are seeking political asylum in the UK. The library has decided that the term ‘asylum seeker’ is bogus, rather than the bona fides of the claimant. Refugee organisations have drawn the same conclusion. There has been no obvious rush to rename themselves: the Asylum Seeker Council would not have quite the same ring to it.

(Moss, 2001, p. 48, emphasis added)

5.2 National identity and diasporic citizenship

National identity is frequently associated with country of origin and place of birth. This association created difficulties for many Jewish refugees in the 1930s who, like Lotte and Wolja, had to flee their country of origin. Despite the fact that he had his German nationality revoked and was stateless, the UK authorities viewed Wolja as ‘German’ because he was born in Berlin. In May 1940, when a German invasion was feared, many such people were deemed to be ‘enemy aliens’ and were arrested and interned, mainly on the Isle of Man. Wolja was interned as a German national whose loyalty to the UK was not absolutely certain. The letters between Lotte and Wolja at this time speak of her attempts to get him registered as ‘stateless’ and to secure his release. His letters express his anxiety about her health and safety and about his parents, now in Romania, his fears that he will be deported to Australia or Canada against his will, without her, and the injustice of his situation.

In one of these (unpublished) letters he asked her to find a solicitor:

He should immediately call on Home Office and establish my non-German nationality. As my departure from here may occur very soon, he should apply for postponement of my departure pending decision of nationality question … it is really a pity that I should waste my time in internment camps although I could do extremely useful work for this country. As the Authorities sometimes object to my having applied for naturalization in Germany, I want you to explain in reply: my parents came to Germany because of antisemitic persecution in their home countries, Rumania and Poland. Thus, in comparison, Germany before the national socialism appeared to me to be a refuge. Then I was persecuted in Germany as a Jew. That is the whole story. Thus there should be no reason not to allow me to continue my work, or some work, for this country. I hope you will succeed.

This letter illustrates starkly that national identity is not fixed or static, but a process which may involve complex negotiations. The Jewish refugees allowed in were those judged to be assimilable into the national culture by adapting to the ‘English’ way of life. The refugee organisations supporting the refugees advised them to be as invisible as possible, and never to speak German in public places (Kushner, 1994). In practice, Lotte and Wolja, like many other refugees, put down roots, made friends, found work and had children. Although the children became more or less ‘invisible’, Lotte and Wolja retained a sense of being viewed as ‘foreigners’ for the rest of their lives. This can be understood in terms of an analysis of the meanings of ‘national identity’:

Nations tend to be imagined as racially and ethnically homogeneous … If the nation is imagined as being made up of people said to be of the same colour and said to have the same ethnic origins, then all those who are defined as not meeting these two criteria can be constructed as being ‘outside’ the nation, as not rightfully a part of it.

(Lewis, 1998, p. 101)

This idea of racial and ethnic homogeneity was taken to an extreme in Nazi Germany, forcing Lotte and Wolja to flee because they were Jewish, even though ‘Jewishness’ had previously not been a central part of their identity. They were constructed as ‘Jews’ by a racist state, and had to construct themselves as ‘Jews’ in order to qualify as refugees and receive financial assistance from Jewish organisations in Germany and England. London (2000) describes the ‘deal’ that the British government did with Jewish communities in the UK to ensure that they would look after those refugees who were allowed in. Such a deal has a contradiction running through it. On the one hand, it depends upon a particular notion of ethnic belonging, and can be seen as one example of ‘diasporic citizenship’: that is, one not premised on the boundaries of a nation-state. On the other hand, it also helps to maintain a hegemonic version of citizenship expressing a natural correspondence between a given state and its constituent population.

The idea of a diaspora – a dispersal or scattering of a population – is a concept employed by postcolonial perspectives. It is used to ‘capture the complex sense of belonging that people can have to several different places, all of which they may think of as home’ (Valentine, 2001, p. 313). The idea of ‘diasporic citizenship’ therefore challenges the assumption that there is a relationship between a particular group or ethnic identity and a particular territory. It recognises that people have multiple identities that derive not only from place and ethnicity, but also from movements between different places, from historical relationships, as well as from religion, gender, class and so on.

Victor's relationship to being ‘British’ illustrates this idea of diasporic citizenship. For him, because of British colonial history, the UK was an ‘imagined home’. But he also saw himself as continuing to ‘belong’ in Fiji. His great-great-grandfather was ‘brought [to Fiji] by the British from colonial India in 1879 to toil on the sugar plantations as “overseas bonded labourer in exile”’ (Lal, 1997, p. 1):

The racist coup also shattered my planned return journey from Oxford to Fiji, and forced me to travel down an unfamiliar road into exile. But, unlike my great-great-grandparents, I was filled with a belief that Fiji was (and still is) as much mine by ‘right of vision’ as it is mine by ‘right of birth’.

(Lal, 1997, p. 2)

Brah's (1996) distinction between two notions of ‘home’ can help make sense of Victor's experience. The first is a sense of home as belonging to a nation:

In racialised or nationalist discourses this signifier can become the basis of claims … that a group settled ‘in’ a place is not necessarily ‘of’ it … In Britain, racialised discourses of the ‘nation’ continue to construct people of African descent and Asian descent, as well as certain other groups, as being outside the nation …

… the second … on the other hand, is an image of ‘home’ as the site of everyday lived experience. It is a discourse of locality, the place where feelings of rootedness ensue from the mundane and the unexpected of daily practice. Home here connotes our networks of family, kin, friends, colleagues and various other ‘significant others’ … the social and psychic geography of space … a community ‘imagined’ in most part through daily encounter. This ‘home’ is a place with which we remain intimate even in moments of intense alienation from it. It is a sense of ‘feeling at home’.

(Brah, 1996, pp. 3–4)

5.3 Legal status and belonging

During the Second World War, Jewish refugees experienced great insecurity about their status, resulting in some cases in severe mental distress. Others ‘chafed at existing conditions. Indeed, most refugees felt they had become part of British Society’ (London, 2000, p. 262). Being naturalised as British citizens was for many ‘the milestone which established their settlement in Britain’ (London, 2000, p. 259).

Following the 2002 Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act, prospective UK citizens were to be required to pass a test to demonstrate ‘a sufficient understanding of English, Welsh or Scottish Gaelic’ and a ‘sufficient understanding of UK society and civic structures’ and ‘to take a citizenship oath and a pledge at a civic ceremony’; the stated aim was ‘to raise the status of becoming a British citizen and to offer more help to that end’ (Home Office Immigration and Nationality Directorate, 2003, Section 1). The first British citizenship ceremony took place in Brent Town Hall in February 2004.

5.3. 1 What would you include in such a test?

An advisory group which drew up proposals for the new ‘Life in the United Kingdom’ naturalisation test, believed that the ‘two senses of “citizenship”, as legal naturalisation and as participation in public life, should support each other. In what has long been a multicultural society, new citizens should be equipped to be active citizens’ (Home Office Immigration and Nationality Directorate, 2003, Section 2).

Although they claimed that becoming British ‘does not mean assimilation into a common culture so that original identities are lost’ (Home Office Immigration and Nationality Directorate, 2003, Section 2), their description of what is required to become an ‘active citizen’ includes ideas of a fixed British way of life, with references to ‘we British’ and to ‘our history’. Becoming an active citizen is said to require as a beginning:

practical and immediately useful knowledge of British life and institutions … If new citizens feel that such guidance is useful, many will want to go on to gain a deeper knowledge of our history, beyond that richer sense of national identity that comes from living in a country over the years and mixing with its settled inhabitants and other new citizens.

(Home Office Immigration and Nationality Directorate, 2003, Section 3)

The Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants (JCWI) suggests that these measures ‘elevate the status of citizenship from a right to a privilege … similar to admission to a private club where the applicant has to convince the existing members that their “face fits the mould”’ (Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants, 2002, p. 3).

Thus citizenship is constructed here as a particular kind of belonging, that of individual and social practices, articulated as practices of the everyday, with a moral dimension, about how ‘we’ ought to behave to one another. It reflects the generalised anxieties over multiculturalism and cultural identity that prevail in the UK in the early twenty-first century, to which postcolonial perspectives draw our attention. Valentine explains it in this way:

transnational migration and diasporic cultures and identities have provoked fears that the boundedness and distinctiveness of individual nations’ cultures are under threat, and that, as a consequence, so too is the nation state … Across Europe legal and illegal migrants (particularly those who are non-white) are being identified as a threat to the economic and cultural well-being of nation states because they are regarded as a drain on the welfare state and as polluting national culture.

(Valentine, 2001, p. 314)

6 Citizenship and access to welfare

6.1 ‘Maybe you can look, but you cannot touch’: asylum and restricting access to welfare

So far we have considered meanings of citizenship in terms of legal status, national identity and belonging. In this section we want to explore it in terms of ‘access to welfare’, recognising that people who flee from their country of origin are likely to require assistance and support when they arrive. There is a long history of the state linking controls on access to welfare and control of migration since the 1905 Aliens Act (Lewis, 2003).

Activity 4

Look again at Table 1 in Section 3. How would you describe the development of policy between 1993 and 2003 in terms of people's access to welfare services and benefits?

Discussion

Successive pieces of legislation attempted to make it increasingly hard for people to enter the country, forcing them in many cases to try to get in illegally, to use agents to help them, or to resort to ‘traffickers’ (Table 2 describes the distinction between ‘agents’ and ‘traffickers’). Their access to welfare benefits and services has also been systematically restricted, on the grounds that welfare acts as an incentive, or ‘magnet’, to make bogus claims for asylum in the UK. Many asylum seekers are detained on arrival in the UK, despite having committed no crime.

This successive removal of welfare services and benefits has had an enormous impact on the personal lives of people who have usually fled terrible circumstances in their country of origin, with dangerous and frightening journeys to get to the UK, which they saw as a place of safety. Such policies and practices affect the most ordinary everyday practices such as whether or not they are able to get enough to eat and somewhere to sleep. The uncertainty of waiting for a decision adds to the level of psychological distress experienced.

We can illustrate this by considering two of the most controversial policies introduced by the 1999 Act – dispersal and the vouchers scheme. Both policies were co-ordinated by a new government body, the National Asylum Support Service (NASS), through which asylum seekers were to be removed entirely from mainstream welfare services.

6.2 ‘No-choice’ dispersal

Dispersal as a strategy aimed at resolving tensions, avoiding ‘concentrations of aliens’ and preserving ‘ethnic balance’ and ‘cultural homogeneity’ is not a new idea, but one proposed for the settlement of successive groups of refugees, and indeed immigrants, since the 1930s, and also used in the 1960s and 1970s in relation to housing and education (Lewis, 1998). The government's asylum dispersal policy of 1999, intended to ‘ease the burden’ of the south-east of England, was based on the identification of suitable ‘cluster areas’ which had, as Smith (2001, p. 13) has noted:

-

available accommodation;

-

a multi-ethnic population or the potential to develop a multi-ethnic population;

-

voluntary or community support structures already in place.

In practice, such aims were hard to realise. Many of the ‘cluster areas’ were in Scotland, and Glasgow City Council was the first Scottish authority to sign a contract (worth £101 million) with NASS to accommodate asylum seekers. Weekly buses brought people on a ‘no-choice’ basis from the south of England. However, the majority of asylum seekers were accommodated in Sighthill: ‘one of the poorest areas of the city’ (Ferguson and Barclay, 2002, p. 2).

Dispersal to Glasgow had a negative influence on claims for asylum being upheld, with claims being rejected on grounds of ‘non-compliance’ (Smith, 2001). The timing and destination of the dispersal took no account of case deadlines or of the need to communicate with solicitors. Like other areas not used to large numbers of asylum seekers, there were very few immigration lawyers or translators in Glasgow. Yet all forms have to be completed in English, and all documents translated into English. Having been dispersed, all enquiries have to be made by telephone, which is much harder in a foreign language. Françoise's experience of dispersal, with her papers going to the wrong address and her appeal being turned down in her absence, is perhaps not uncommon.

The dispersal policy shaped the everyday lives of asylum seekers; they experienced it as a deprivation of human rights by cutting them off from friends, family and community. It conditioned the dynamics and circumstances of their relationships with others – strangers as well as friends and family. Many resisted dispersal, preferring to make their own arrangements or to return to London or the south-east, although this would make them ineligible for any welfare support.

Nevertheless, asylum seekers' experiences were contradictory. They were relieved to be free from the danger that had led them to flee and referred to the friendliness of the Glasgow people. However, there were high levels of hostility and racist attacks against them, culminating in Sighthill in 2001 in the murder of a young Turkish Kurd, Firsat Dag:

Out of the horror evoked by such events, however, some good emerged … One of the most moving and inspiring events of that time was the large demonstration into Glasgow town centre of asylum seekers, local Sighthill people and many others appalled by Firsat's murder under the banner ‘Sighthill United Against Racism and Poverty’.

(Ferguson and Barclay, 2002, p. 2)

6.3 Shopping with ‘vouchers’

Activity 5

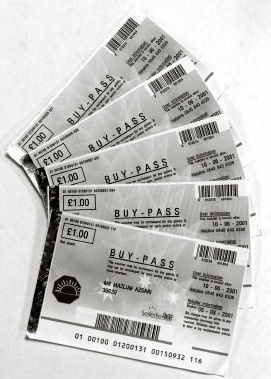

The advice given to young asylum seekers, reproduced here as Extract 4, describes how the system of vouchers (see Figure 4) operated before it was discontinued in 2002 (other details of the scheme are given in Table 1). How might this have shaped their personal lives?

Extract 4: ‘How do I buy food and other everyday items?’

If you are being supported by NASS, you will receive vouchers so that you can buy food and essential everyday items. These vouchers are issued by a company called Sodexho. You will probably receive emergency vouchers when you first arrive, but later you will have to collect them each week from a Crown (main) post office near to where you are living.

You can use the vouchers only at selected shops. Your landlord can tell you the names and addresses of these shops in your area. Alternatively, look for shops displaying the Sodexho BUY-PASS symbol in their window. You will also receive £10 cash each week that you can use for travel costs and for purchases from any shop.

Shops will not be able to give you change from a voucher so make sure you get enough low value vouchers (they are available in amounts down to 50 pence) and try to spend up to the full amount.

Discussion

The advice did not explain that the total value of the vouchers was set at 70 per cent of income support, nor that vouchers, unlike other social security benefits, did not entitle people to other benefits or services such as reduced admission charges.

While shopping, an activity that most of us carry out automatically, asylum seekers were constructed as ‘other’:

I feel we are marked in red because everyone knows we are refugees when we do our shopping by voucher. We feel humiliated at the checkout because when we give our vouchers, the cashier's attitude is usually really bad. Usually, when they tell us the total, they won't let us go back to pick up something for the change … Other customers who are in the queue behind us … often look at us in a very bad way, like: ‘Look at this asylum seeker, they are here, they are buying things with vouchers and they are holding us up.’ We try to be very fast and sometimes we end up making mistakes at the cash desk.

(Fatma, quoted by Gillan, 2001, p. 41)

This is a graphic illustration of the idea within Foucauldian post-structuralism that power resides not only in the state, but is dispersed throughout society through a range of human interactions and sets of relationships. In this instance, the ‘power to humiliate sits behind the till’ (Gillan, 2001, p. 41).

The policy was criticised by all organisations involved with asylum seekers, by many trade unions and the British Medical Association, and in an Audit Commission Report (2000), for being inhumane and stigmatising as well as bureaucratic and inefficient. In October 2001 the government agreed to phase out the scheme, but refused to return to providing cash benefits. Instead, asylum seekers would be housed in new reception and detention centres as these became available.

The 2002 Act further limited the access of asylum seekers to welfare, with even this limited support ending when they gained refugee status. Under Section 55, support was only available for those who applied for asylum ‘as soon as reasonably practicable’ after arrival in the UK, even though 65 per cent of people who received positive decisions had made so-called ‘in-country’ claims (Refugee Council press release, 19 February 2003). Refugee, human rights and homelessness organisations warned that it would leave ‘in-country’ asylum applicants literally destitute of the right to food or shelter. In contrast, the Home Office believed that ‘if they have been staying off the streets and managing for the weeks, months or years before they claimed asylum, then there's no reason why they should not continue to do so’ (Prasad, 2003, p. 2). The way the policy was administered resulted in ‘people … being refused support despite applying within days, sometimes minutes, of arriving in Scotland. Refugees ended up having to sleep rough and go hungry simply because they were traumatised, did not know the procedures or spoke no English’ (Scottish Refugee Council, 2003, p. 1).

Here we have an example of the way in which such policies and practices are contested, in this case by voluntary organisations. In March 2003, following legal action taken by the Refugee Council and other organisations, the Appeal Court ruled that the implementation of Section 55 was unreasonable (Refugee Council, 2003a). Nevertheless, one newspaper reported that ‘huddles of asylum seekers have begun visibly sleeping rough in central and south London … They have had letters from the government denying them support, in effect leaving them on the street, where they have been setting up permanent “homes” – gathering cardboard boxes’ (The Guardian, 18 August 2003, p. 7).

The 2002 Act also introduced the development of a new type of large accommodation centre, which because of its size (housing 750 people), was to be sited in rural areas, in contrast to the original dispersal ‘cluster areas’. Asylum seekers would only receive a small cash allowance, forcing them to stay at the centre for food and lodging, thus denying them such everyday practices as shopping and cooking. For the first time children were to be removed from mainstream schooling and educated within the centres.

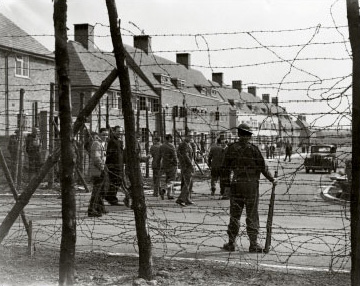

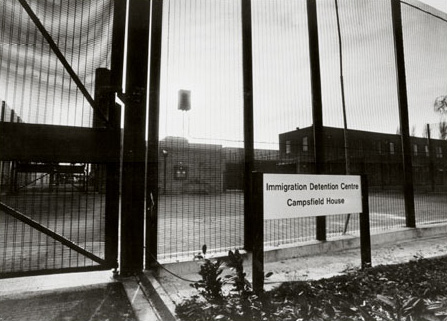

Refugee organisations argued that the Act sought to maintain high levels of monitoring and surveillance of asylum seekers, through a system of induction, accommodation and detention centres. They feared that accommodation centres could easily become locked detention centres (see Figures 7 and 8 for a historical comparison), and that they would ‘extend social division by ensuring that asylum seekers are effectively segregated from mainstream society’ and ‘become inevitable targets for racist attacks with barbed wire and security guards becoming a feature of these centres’ (Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants, 2002, p. 4). Many local communities campaigned against such centres in their areas, ‘gripped by what … [the] residents admit is “a fear of the unknown” … They envisage men wandering their streets, skulking. They talk of threats to their children, of locking their doors, of terrorists. They admit they have no evidence for any of this’ (The Guardian, 6 February 2003, p. 11). Despite this opposition from refugee organisations and local communities, the Home Secretary was determined to press ahead with the centres, as they would ‘ensure the application process is speeded up … he also insists that the centres will ensure applicants do not drift away’ (The Guardian, 20 August 2003, p. 9).

7 Citizenship as ‘participation in social life’

If ‘citizenship, as social practice, is manifested by direct or indirect participation in public life, by both individuals and groups’ (Kastoryano, 2002, p. 143), then opportunities for asylum seekers and refugees to participate is crucial. Young unaccompanied asylum seekers in Milton Keynes (not one of the government's ‘cluster areas’) were very clear about what participation meant for them: ‘secure housing, full-time education, special language training, friends and community support, leave to remain and a secure future: “To learn English … To go to school … To marry an English girl … To learn about computers … To become a doctor … To be useful for the society”’ (John et al., 2002, p. 6, original emphasis).

Policies on vouchers, dispersal, accommodation and detention actively discouraged participation in public life. However, in 2001 the Labour Government gave an election commitment to assist the settlement and integration of refugees into UK society, though integration was only to be facilitated for people with refugee status or indefinite leave to remain in the UK, even though the greatest need for help is immediately after arrival. Thus, free English language classes were only available in England for people with three years’ residence or refugee status (the situation is more flexible in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland). The education of children within accommodation centres has particular consequences for women and children, since involvement with schools is a good way of making friends and feeling part of a community.

Engagement in paid employment has long been seen as a key aspect of citizenship, both as a responsibility and as a right guaranteed by the state (Mooney, 2004). However, this opportunity has been limited for both asylum seekers and refugees, exacerbated by dispersal policies and removed entirely for asylum seekers by the 2002 Act. From Table 1 we can see that structural barriers to employment stem directly from immigration and asylum legislation, and asylum seekers themselves find it paradoxical that they are accused of sponging off the state but denied the right to work. At the time of the 2002 Act the government was also developing a ‘Highly Skilled Migrant Programme’ to encourage people with exceptional skills and experience to come to the UK to work. This had very little impact on those asylum seekers and refugees eligible to work, who have consistently found it hard to obtain employment. Most experience downward mobility, despite many of them being highly qualified in areas of serious shortage such as teaching and medicine. Discrimination by employers is seen as the main barrier to participation in work (Bloch, 2002). Many asylum seekers have been forced into the informal economy, working in unpopular jobs in catering, cleaning, building, farm labouring and food production. They are poorly paid, greatly exploited and further demonised for doing these jobs.

In a survey of 400 asylum seekers and refugees from five different communities, Bloch (2002) investigated the experiences of participation and employment of people eligible to work. Some of her findings are set out in Extract 5.

Extract 5: Participation and employment experiences of some asylum seekers and refugees eligible to work

-

Most people had made new friends since arriving in the UK; this was important for participating in activities and feeling less marginalized. Women were more likely than men to have friends only in their own community. Kinship and community networks were very important; those who had moved had done so largely to be near family or friends or because of the existence of a community.

-

Most people were literate in their first language and more than half were multi-lingual; most people's English language skills were not good when they arrived, but improved rapidly through language courses; access to language classes was harder for women with children.

-

There was a low level of labour market participation even though 96 per cent had had formal education, 56 per cent had a qualification on arrival and 42 per cent had been working before coming to the UK; more men were employed than women, but in a much lower diversity of work than before coming to the UK; few people had professional jobs; most had poor terms and conditions of employment.

-

Few people were studying or in training; this was due to insufficient language skills, not knowing what was available or they were entitled to, lack of child care or family commitments.

These findings spell out clearly some of the barriers to citizenship as participation in social life.

8 Knowledge and evidence

8.1 How is ‘knowledge’ about refugees and asylum seekers produced and reproduced?

In this final section we consider ways in which ‘knowledge’ about refugees and asylum seekers is produced and reproduced through different kinds of research.

8.1.1 What kind of evidence has been used in this course?

We have used personal stories as evidence to support arguments about the mutual constitution of personal lives and social policy. The people in our stories all came to, or stayed in, the UK primarily because they saw it as a place of safety, not because of the welfare benefits or services they hoped to receive, and we have contrasted this with dominant discourses about (bogus) asylum seekers for whom welfare in the UK is said to act as a magnet. These dominant or official discourses, echoed by the media, focus on evidence, often described as ‘facts’, which is used to justify ever harsher procedures and removal of welfare services and benefits. A typical example, shown in Extract 6, is taken from a Home Office press release from February 2003; it presents the ‘asylum statistics’ for the final quarter of 2002. The government used these figures as a benchmark to measure its progress in meeting its declared target to ‘cut asylum claims by 50 per cent’ (Home Office, 2003).

Activity 6

Have a look at Extract 6.

-

What might we learn from the data in this extract?

-

Given the purpose of the figures as stated above, what implicit assumptions characterise this approach to obtaining evidence?

Extract 6: Some asylum statistics for the final quarter of 2002

The key findings of the publication of the 4th quarter statistics are:

-

There were 23,385 applications for asylum in the 4th quarter of 2002;

-

There were 85,865 applications in 2002 (estimated 110,700 including dependants). Since peaking in October at just under 9,000 there has been considerable progress, falling to 7,815 in November and 6,670 in December as the NIA Act [The Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002] began to come into force and the effects of increased security with the French reduced the number of illegal immigrants entering Britain;

-

…

-

In 2002 8,100 (10 per cent) people were granted asylum, 19,965 (24 per cent) were granted ELR [exceptional leave to remain] and 54,650 (66 per cent) were refused asylum;

-

A record number of failed asylum seekers were removed in this quarter (3,730). 13,335 failed asylum seekers were removed in 2002 – a record annual figure. …

-

NASS received 10 per cent fewer applications for support in this quarter (17,450);

-

By the end of December 2002 37,810 asylum seekers were receiving subsistence only support and 54,070 were supported in NASS accommodation.

Discussion

We identified the following assumptions:

-

Apparently neutral phrases like ‘asylum statistics’ mask the fact that the statistics imply that ‘the real reasons’ people want to come to the UK are to take advantage of the UK's ‘lax’ asylum laws and generous welfare state.

-

‘Facts’ always refer to numbers, which are assumed to be too high.

-

The language of the statistics shown in Extract 6 gives no insight into people's experiences or the reasons for their applications.

-

The term ‘record number of failed asylum seekers’ assumes that most of the claims were not ‘genuine’.

-

The idea of setting a target on a reduction in the number of claims is based on this same premise. It takes no account of the circumstances in the world that cause people to flee. Nevertheless, in commenting on the ‘provisional figures for 2002’ as ‘deeply unsatisfactory’ the Home Secretary referred to such world events, suggesting it was ‘no surprise, with applications from Iraq and Zimbabwe accounting for nearly all the increase from 2001’ (Home Office, 2003).

-

The use of labels like ‘asylum seeker’ serves to homogenise people's experiences.

‘Statistics’ do not always support such dominant views. A counter example comes from a challenge by the Refugee Council to the association made between asylum seekers and ‘terrorists’ in early 2003, following the shooting of a policeman in Manchester. They refuted this association with their own ‘facts at a glance’ (see Table 3).

| 22.8 million |

| The number of people who came to the UK in 2001 for stays of up to one year, including tourists, business travellers and overseas students |

| 88,300 |

| The number of asylum applications made in the UK during 2001 |

| 3 |

| The number of asylum seekers being held under anti-terrorist legislation |

Research that is interested in the experiences of asylum seekers and refugees does not collect statistics, but uses qualitative methods such as interviews or focus groups. For example, Robinson and Segrott (2002) conducted interviews with 65 asylum seekers to understand the decision-making of asylum seekers. The choice of in-depth interviews as the research method arose from the researchers'

beliefs about human agency and its complexity and rootedness in individual biographies … this was the only way that the practical consciousness of the respondents could be explored, and the depth and quality of information that is needed be gained … given the potential complexity of the decision making process.

(Robinson and Segrott, 2002, p. 8)

Recruitment of respondents, through contacts and organisations, was not straightforward. Not surprisingly, asylum seekers, whose status is still uncertain, may be quite anxious about participating in research, and wary of trusting anyone who seems at all ‘official’. In particular:

there was reluctance to participate in a study being funded by the Home Office, even though it was emphasized that this research was independent … the Home Office's role was solely as funders … The research met considerable suspicion about its motives, rooted in a belief that Home Office involvement in the project reflected a hidden agenda.

(Robinson and Segrott, 2002, p. 9)

People were persuaded to participate because the researchers gained their trust, partly through personal contacts, and partly through their credibility as researchers. In addition, the asylum seekers believed that they ‘would have an opportunity to speak directly to the Home Office through this research’ (Robinson and Segrott, 2002, p. 10).

Robinson and Segrott found that people's overwhelming concern was to find a place of safety. Factors influencing their final destination included: their ability to pay for long-distance travel and whether they were dependent upon ‘agents’ who made the decision for them. If in a position to choose, they were influenced by having relatives or friends in the UK, the belief that the UK is a safe, tolerant and democratic country, previous links between their own country and the UK, including colonialism, and the ability to speak English or a desire to learn it. There was little evidence of prior knowledge of UK immigration or asylum procedures, of entitlements to benefits or availability of work in the UK. There was even less evidence that asylum seekers had comparative knowledge of how these varied between different European countries. Most wanted to work and support themselves during the determination of their asylum claim rather than be dependent upon the state.