Remaking the relations of work and welfare

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 19 April 2024, 2:48 AM

Remaking the relations of work and welfare

Introduction

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of Level 3 study in Social sciences

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

outline the ways in which the relations between work and welfare are made and remade in different places and at different times

explain how these changing relations contribute to constituting welfare subjects

describe how welfare provision that is connected to work affects the lives of different welfare subjects in different and unequal ways

assess the relative influences and effects of the economic, developmental and social purposes of welfare programmes based on work

identify appropriate evidence for assessing such programmes, and make a critical evaluation of it.

1 Welfare, work and social policy: an overview

On 29 February 2000, a 6-year-old boy in his first year at Buell School, Beecher, in the town of Flint, Michigan, in the USA, took a .32 calibre handgun to school and shot 6-year-old Michaela Roland dead with a single bullet. The boy had been staying with his uncle because his mother, Tamarla Owens, had been evicted from her home for lapsing on her rent payments, despite working up to 70 hours a week in two jobs to maintain her two children. Tamarla Owens was not there that morning to see her son find the gun and take it to school because she had already set out on her three-hour round-trip bus journey to Oakland County, where she worked as a waitress and as a bartender in Dick Clarke's American Grandstand Grill. She was required to make the journey as a condition of the State of Michigan's welfare-to-work programme.

Beecher is the one-time home of General Motors and a huge car production plant, long since derelict and surrounded by a community in which 87 per cent of children live below the official poverty line. With no work available nearby, Tamarla Owens joined the daily bus-full of workers who went to service the affluent residents of Oakland County in return for US$5.50 (about £3) an hour. Dick Clarke's restaurant chain sought special tax breaks for its service to the community in placing people on the programme.

In the County Sheriff's Office immediately after the shooting, Tamarla Owens's son was given crayons and paper. He drew a picture of a child, alone, beside a tiny house (see Figure 1).

Tamarla Owens is a black lone mother. Her story was made famous in Michael Moore's Oscar-winning documentary film Bowling for Columbine (2002), about the mass school shooting in Littleton, Colorado, in April 1999. In the film, the driver of Tamarla Owens' bus says that she went to work every day.

Her manager at the Grandstand Grill commends her as a good worker. And the Sheriff argues forcefully that the welfare-to-work programme should be closed down because it prevents parents with sole responsibility from caring for their children.

The US ‘workfare’ programmes (as they are often known) of the 1990s have been celebrated as successes and taken-up as profitable private enterprises by firms as prestigious as Lockheed Martin, the giant armaments manufacturer, which runs many of them. The Temporary Aid for Needy Families Programme was established by the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) of 1996. These programmes have been venerated as having solved ‘the welfare problem’ (Rogers, 1999; Clark and Hein, 2000; Peck, 2001). And they have epitomised the ways in which welfare policies are developed around particular constructions of personal lives, and go on to shape those lives in profound ways.

Few will be as profound as the ways in which Michigan's programme shaped Tamarla Owens' life. But, despite the exceptional nature of the Buell School tragedy, Tamarla Owens' story carries within it many of the key narratives of the transformation of welfare policy through welfare to work. It is emblematic of them, in that Tamarla Owens is black, poor and a lone mother. But it is also typical since it highlights a range of issues concerning how personal lives and social policies intersect. It raises questions about the sources of her poverty in a town whose main economic base has collapsed. It challenges social priorities when financial self-sufficiency and parental responsibility are in conflict. And it opens debate about whether the purpose of workfare is to save the state money, to reduce labour costs, to train an unskilled workforce or to discipline a population. Cutting across all these questions, Tamarla Owens' story raises issues about how ‘race’, gender, sexuality and class shape the ways in which ‘the personal’ is interpreted in the development of social policies, and how these policies might work to ‘remake’ those facets of the personal lives of welfare subjects. Addressing these questions, the issues they raise, and the theoretical frameworks they invoke, are the central aims of this course.

Where the articulation of welfare with work is closest, in workfare regimes like those of the USA, the impact of policy on almost every aspect of ‘the personal’ is potentially profound. For Tamarla Owens, it is not just daily routines that are directly determined by policy, but it is also how her life is ordered, the way she experiences the community she lives in, how it regards her, and who she becomes, that are affected. These also affect the personal lives of those around her – tragically so if the Sheriff's interpretation of events holds. But, in less extreme forms, in more moderate regimes that connect welfare to work, ways of conceptualising rights and entitlements are shifting, ‘common-sense’ ideas about welfare are changing, and how welfare subjects are constituted is being reworked in ways which are built on, and have consequences for, how we understand personal lives. Understanding how welfare and work are connected in contemporary social policy does not just give us an insight into an important aspect of the workings of the welfare system. It also provides a significant way of understanding how individuals and groups become constituted as welfare subjects. The processes through which this takes place are the first and central theme of this course.

Though we know little of Tamarla Owens' personal history, it is likely that some aspects of her personal life resemble the stereotypical constructions and representations that underpin discourses which lead to workfare reforms. She will have been regarded as welfare-dependent, since she lacked work, perhaps because she had limited skills or qualifications, and, especially, as she was a lone parent. The so-called ‘trap’ of needing to work to maintain children, but being unavailable to work while caring for them, has been the most intractable welfare conundrum with which governments grappled during the 1990s in pursuit of their commitment to reducing welfare spending (see Thomson, 2004). Pathologising constructions of blackness, lone parenthood and welfare dependency became key discourses in the steady shift of welfare policies towards workfare. How welfare, in the form of income maintenance, touches the lives of different groups unequally is the second theme of this course.

The events in Flint, Michigan, raise critical questions about the social, political and economic purposes of workfare. Is it primarily helping to keep pay and taxes low and match people to jobs? Is it providing work experience that will help unemployed people into jobs? Or is it serving as a deterrent to Tamarla Owens and others having more children? The first of these questions imagines the purposes of workfare to be economic; the second views it as developmental; the third as disciplining personal conduct. Determining which of the three purposes of workfare is supportable and whether they are compatible or contradictory is the third theme of the course.

Assessing these explanations calls for evidence about the circumstances that give rise to workfare programmes. Most social scientists would also want to hear Tamarla Owens' own account of the programme and its impact on her personal life. But her account alone would not allow us to reach an informed view about the programme. If we are to understand the programme's impact on personal lives in the wider context of welfare provision, taxation and labour markets, for example, we would need some broader evidence about its costs and effects on employment. We would want other accounts that represented a diverse range of people and experiences. We might also want to consider categories of people and evidence of inequalities in the ways they are affected. So there is a wide range of evidence that would inform a debate about how workfare constructs the intersection of policies and ‘the personal’. Finding appropriate evidence and judging its value for assessing workfare is the fourth theme of the course.

Assessing and interpreting evidence cannot be undertaken without a theoretical framework within which disconnected facts can be formed into a reasoned argument. No amount of evidence about the circumstances of those who are assigned to workfare will produce an assessment of it unless it is woven into a coherent theorised narrative. Four very different theories provide the framework for the course:

Neo-Marxism focuses on the contradictory place of welfare in market-based societies committed to the maximisation of profits.

Post-structuralism looks at the networks of power that lie behind the relations of work and welfare, and aims to understand how the actions and conduct of unique, autonomous individuals are governed in them.

Feminism looks at the distinctive position of women and at the production of differences and inequalities of gender, through the power relations of welfare structures and personal interactions of individuals.

In addition, this course highlights key aspects of a neo-liberal approach, in particular neo-liberalism's concern with optimising economic rationality and minimising welfare to secure the unhampered working of markets.

Workfare is a particular way of remaking the relations between work and welfare, and it epitomises some of the ways in which policies and ‘the personal’ intersect. The forms taken by these relations often shift at critical transition points in personal lives: at retirement, for example, and, as this course will show, when people begin work or become parents. To pursue the themes we have set out, we need, first, to trace some of the ways in which the relations between welfare and work have been repeatedly remade historically. Embodied in every different version of these relations are distinctive constructions of how ‘the personal’ has shaped policies and how policies have shaped personal lives.

2 The contingent relations of welfare and work: from workhouse to workfare?

2.1 Background and historical overview

As we saw in Section 1, everyday talk, public discourse and political debates sometimes treat the concepts of ‘welfare’ and ‘work’ as separate spheres of activity, or even binary opposites: welfare or work. This can occur in different ways, for example:

-

an explicit connection is drawn between welfare and work, as though they were directly dependent upon one another: welfare and work, work for welfare, welfare to work;

-

the connection is implicit: welfare and work as interweaving patterns over a lifetime;

-

the connection is treated as an objective, perhaps in the phrase welfare to work;

-

the dependency is more explicit, as in ‘working for welfare’;

-

in some versions, it is clear that welfare is not offered without work, as is suggested by collapsing the two words: ‘workfare’.

All these mixes of the concepts of ‘welfare’ and ‘work’ are captured in the word ‘contingent’: it refers to a set of relations in which welfare and work necessarily connect, but in a very wide variety of ways, from potential link to complete interdependency.

It would be possible to take distinctive welfare systems and ‘map’ them according to the different ways in which the relations between welfare and work have been made at different times, for different social groups and in different places. But, even the briefest mapping leads rapidly towards an important, and perhaps rather startling, realisation: the decades that followed the post-war welfare settlement in the UK were historically unique in a number of ways, because they established a degree of separation between the entitlement to welfare and the obligation to work.

Two points of contrast highlight this. In the UK, the involvement of the centralised state in the relief of the poor after the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act made the contingent nature of welfare-work relations more highly visible than they had ever been. The welfare system drew unemployed men, their families and unmarried mothers into workhouses as their sole access to welfare, and so established the principle that state welfare was conditional on commodified work. On the same principle, a century later in the USA nationally provided state welfare began with Roosevelt's New Deal, and the Works Administration Programme, that allowed states to require the involvement of those seeking benefits in public works.

Between these two starting points, the welfare polices that took Tamarla Owens on the bus to Oakland County, and the recent development of welfare-to-work programmes in the UK, have two long and disparate histories. In the UK, the Poor Law shaped provision for the unskilled, for some women and for most racialised minority groups for the best part of a century. The conditional connection between welfare and work was incrementally relaxed for other groups between 1911 and the post-war settlement. From then until the late 1970s, as we have noted, welfare entitlement and work obligation remained much more loosely connected for most of the population.

In the USA, unconditional entitlement was largely restricted to lone parent families with dependent children. The pressures on them to participate in ‘public works’ or ‘community-based’ programmes grew during the 1960s, shifted towards a stronger emphasis on support and training in the 1970s, then began a transition from facilitative welfare-to-work incentives, to mandatory work-for-welfare conditions, with sanctions for those who refused or withdrew, during the 1980s and 1990s (Burghes, 1987; Peck, 2001). In 1996, the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) made all benefit entitlement entirely conditional upon work, except for lone parents whose first child was below school age. This is the form of relations referred to as workfare.

A parallel trend affected the UK from the 1980s onwards, once the disruption of the post-war welfare settlement had begun (Lewis, 1998). At first, the focus was largely on facilitative incentives, and there was a gradual move towards job-search requirements, participation in workshops and careers advice and vigorous encouragement of lone parents to take work. In 1986, 16- to 18-year-olds lost all benefit entitlement and were required to join youth training programmes, many of which entailed work placement. In 1997, New Labour's New Deal marked the highly significant switch to mandatory forms of participation in work placement or training.

2.2 Rationales for conditional entitlement to welfare

The contingent relation between work and welfare has moved – unevenly over time and place – between extremes of conditionality and separation, with long periods of more complex relations that varied for different social groups and between localities. Early in the twenty-first century, in the UK and the USA, there is a powerful trend towards a return to the conditional nature of welfare with which state involvement began. What underlies this pattern of the rise and fall of unconditional entitlement to welfare for some provides a key to understanding how welfare policies and personal lives constitute one another.

Three rationales have been used by those who advocate conditional relations between welfare and work.

Economic-regulatory rationales are based on the workhouse principle of ‘less eligibility’, which sought to encourage participation in the labour market by depriving workhouse inmates of material comforts. If the conditions of welfare provision are equal to or better than the conditions of those earning the lowest rates of pay, they leave employers short of workers and exert inflationary pressure on wages. So, if the least skilled workers are to choose low paid jobs, not welfare, benefit levels must always be less desirable, or ‘less eligible’. Here, Tamarla Owens' low wages provide some income and reduce the wage bill of employers like Dick Clarke.

Personal-developmental rationales stress the importance of developing the skills base of the workforce in a competitive international economy. For those on the margins of work and welfare, enhancing employability is the key to reducing welfare costs and strengthening the economy. This may be best achieved by subsidised work experience, by job creation through public works programmes, or through education and training. Here, it is the skills gained from the experience of working that will benefit Tamarla Owens, while also serving the interests of restaurant-goers.

Social-disciplinary rationales focus on the supposedly debilitating effects of welfare as a response to worklessness, stressing instead habits of industriousness to an impoverished and supposedly ‘demoralised’ class which becomes feckless and idle when lacking employment. On this reading, the workhouse was inspired by inculcating good behaviour and policing ‘degenerate’ behaviour. It is the moral effects of welfare dependency that are damaging. ‘Remoralising’ the poor by making welfare dependent on participation in work is therefore the main purpose of work programmes. It is the act of being on the early morning bus every day and being a good worker that benefits Tamarla Owens.

These rationales overlap, yet each embodies distinctive assumptions about the personal lives of those in need of welfare. In some cases, this is no more than a broad theory about human conduct. Neo-liberals who have drawn on the economic-regulatory rationale, for example, build their argument around the belief that people are rational economic actors who make calculated self-interested choices to optimise their own well-being. Reformists who use the personal-developmental rationale trace the need for welfare in shortcomings in individuals' abilities to compete for jobs. Alongside deprived backgrounds and poor provision, they portray personal lives marred by lack of self-respect and confidence.

In contrast, neo-conservatives use the social-disciplinary rationale to depict an underclass of demoralised welfare dependants who lack hope. Neo-conservative remoralisation discourses and their constructions of personal lives have exerted a particularly strong influence over the shifting contingency of welfare and work, notably in the USA, but also in the UK.

Activity 1

Read the following quotations from two influential US authors. Make a note of how each quotation construes the place of ‘the personal’ in welfare and identify any significant differences in their approaches.

… surprisingly little has been made of the distinction between the behaviors that make sense when one is poor and the behaviors that make sense when one is not poor.

(Murray, 1994, p. 156)

Self-sufficiency [is] no longer taken to be an intrinsic obligation of healthy adults.

(Murray, 1994, p. 180)

A greater number [of poor adults] are simply defeatist about work or unable to organize their personal lives to hold jobs consistently.

(Mead, 1997, p. 12)

… bureaucracy – unpopular though it is – increasingly must manage the lives of those who are seriously poor.

(Mead, 1997, p. 14)

Discussion

Personal lives are regarded as the source of welfare dependency, but the first two quotations see claimants as rational, the second two as demoralised. Charles Murray's (1994) work, from which the first two quotations come, was highly influential on welfare policy-making in the USA in the 1990s. It focused on the formation of a welfare underclass, particularly amongst black American lone mothers and unemployed fathers. He identified what he viewed as their rational self-interest in responding to the ‘perverse incentives’ of the US welfare system in the 1960s and 1970s to qualify for welfare by having ‘illegitimate’ children as a means to gaining income and security in the face of poor job opportunities. While his work is infused with assumptions and implications about the personal lives of black Americans, his focus remains on their pursuit of their own best short-term interests by ‘using’ an ill-conceived welfare system to their advantage (see also Morris, 1998).

Lawrence Mead (1997) is the author of the second two quotations. He shared many of Murray's views of welfare, but had a significantly different analysis. To Mead it was the personal conduct of impoverished welfare claimants that was the key to their dependency. Their need for welfare is a reflection of their worklessness, which in turn is the product of individual de-motivation, despair and self-defeat that result from a ‘culture of poverty’. As the third and fourth quotations suggest, Mead was not persuaded by the standard explanations for dependency. To him, the main cause of poverty ‘is no longer social injustice but the disorders of (dependants’) private lives’ (Mead, 1997, p. 15). This view is echoed by some conservatives in the UK. Green (1999), for example, depicts the stereotypic self-destructive behaviour of an unqualified, unskilled school-leaver and father of illegitimate children, for whom only a change of attitude from within will bring an escape from dependency. It is this ‘new politics of conduct’ (Deacon, 1997, p. xv) and its social disciplinary rationale that underpin their arguments for constructing a binding connection between work and welfare.

It is vividly clear that these commentators locate poverty and the need for welfare in personal lives and ‘pathological’ behaviours. It is unskilled men, lone mothers and the black population whose personal lives are implied to underlie the need for welfare. The influence of these commentaries on government policies has been extensive, as much because of their work of legitimising and authorising perceptions and representations as by originating them (Deacon, 1997; Clarke, 2001). And it is through these processes of discursive construction, in which particular readings of individual circumstances become sedimented into dominant truths about the causes of poverty and ‘dependency’, that representations of personal lives come to shape social policies.

3 Personal agency, participation and refusal: gathering evidence

While it is difficult to exaggerate the impact of this construction of ‘welfare dependency’, particularly in the USA, this construction does not go unchallenged. A very wide range of groups of people who are poor or who are subject to discrimination succeed in shaping welfare arrangements by evading, refusing or resisting policies. Historically, there are numerous examples of collective agency in resisting and reshaping welfare policies. In the USA, Fox Piven and Cloward (1977) trace the history of poor people's movements that began around the time of Roosevelt's New Deal, and continued with the considerable successes of the industrial workers’ movement and the civil rights movement.

Some comparable movements are well-known in the UK, most notably the hunger marches and the Jarrow March of the 1930s depression, but there are also numerous other effective protests against poverty by welfare rights groups, claimants' unions and feminist campaigns against cohabitation rules in the 1970s and 1980s.

More recently, resistance to workfare policies has taken a number of forms. Least common, but with a stronger history in Canada and the USA, are active forms of explicit political protest. Swanson (1997) describes an extended campaign that delayed the introduction of workfare in British Columbia in the mid 1990s. Protesting groups took their cause to the United Nations on the grounds that workfare breaches the UN Covenant on Social Economic and Cultural Rights, which requires signatory nations to allow their citizens to earn a living by ‘freely chosen’ work.

In Quebec, resistance was registered by community groups who, as prospective employers, were eligible to take on workfare clients. They boycotted the programmes as inequitable and as causing ‘job substitution’ (Shragge and Deniger, 1997). Swanson describes trades unions' protests in New Brunswick over job substitution, which attracted much popular local support, and successful prosecution of a legal grievance. Abramovitz (1996) catalogues an extensive range of protests by women activists in the USA against workfare reforms. These may have made some contribution to the continuing protected position of lone mothers while their first child remains below school age under the PRWORA.

Such resistance undoubtedly represents only a small part of the picture. But although workfare polices have a major impact on the lives of those who come within their ambit, the processes of policy implementation are not smooth and mechanical. Both in express protest, and in their efforts to accommodate their lives to policy demands, groups and individuals act to obstruct or amend policies. Horton and Shaw's (2002) study of the Los Angeles workfare programme found disappointment among claimants with humiliating and rigid bureaucratic procedures, which produced complaint and resistance. Bringing together claimants produced solidarity, raised collective awareness of the faults of the programme, and expressed criticism of the policy-makers' ignorance of their difficulties.

Kingfisher's (1996) analysis of women's narratives about US welfare found them appropriating dominant views for subversive, resistant purposes. They appeared to accept and adopt the categories used by policy-makers, while deploying them to define themselves outside these categories as responsible mothers, committed workers and as reluctant to be dependent. Through such ‘reverse discourses’, Kingfisher argues, women confront the contradictions of the system.

There are also important questions about the extent to which withdrawal and non-participation constitute resistance. In his extensive study of youth training in the 1980s and 1990s in the UK, Mizen (1994) argues that participation in schemes was infused with scepticism, reluctance and a deeply instrumental attitude on the part of trainees who saw through bogus claims of quality training and subverted attempts to manage them. Rates of refusal and early leaving were consistently high, thus subverting many of the programmes' personal development claims. Hollands's (1990) study pointed to the ways in which schemes fostered ‘workless cultures’, involving deliberate, and sometimes politicised and collectivised, avoidance.

How far these responses go beyond cultures of avoidance and non-cooperation to constitute resistance is less clear, not least because it is exceptionally difficult to find evidence of the significance of refusals and withdrawals in the evaluation data on workfare programmes. One way of getting a glimpse of how far people participate, avoid or resist welfare to work is to look at the evidence from the first mandatory programme in the UK – the New Deal for Young People (NDYP).

Since 1998, 18- to 24-year-olds who have been claiming job seekers allowance (JSA) for six months have been required to join the New Deal programme. Following a ‘Gateway’ period of intensive counselling, advice and job search guidance with a Personal Adviser, clients choose between a job with a training component (subsidised placement with an employer, the Environmental Task Force or a community project), and full-time education or training. Clients who gain subsidised employment are paid at the market rate set by their employer. Others receive a weekly allowance fractionally above the minimum JSA rate. Clients are sanctioned by withdrawal of the allowance for repeatedly refusing placements, absenteeism or drop-out. In practice, some clients remain in place for the whole programme, some leave during the Gateway period during their placement on a job or course, or before they complete a job search afterwards.

It is difficult to gather clear information about the point at which they leave, what happens to some leavers immediately afterwards and the longer-term outcomes. Government data used to monitor the NDYP comes in the form of monthly statistics which provide some basic information.

Activity 2

Examine Table 1 carefully. Make notes on what you can gather about participation, dropout and completion, and about differences between the groups identified. As you do so, think about the kinds of explanations you would expect to find for the differences between social groups in patterns of participation and outcomes from NDYP.

| All | % | Male | % | Female | % | People with disabilities | % | Whites | % | Ethnic minorities | % | No qualifications or below NVQ Level 2 | % | Qualifications NVQ Level 2 or above | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9,942 who have had a first New Deal interview in October 2001 of which: | 9942 | 6964 | 2956 | 1226 | 7745 | 1747 | 3569 | 1099 | ||||||||

| As a percentage of all | 100 | 70 | 30 | 12 | 78 | 18 | 36 | 11 | ||||||||

| On an option: | 323 | 100 | 244 | 100 | 77 | 100 | 57 | 100 | 246 | 100 | 57 | 100 | 156 | 100 | 41 | 100 |

| Employment | 34 | 11 | 26 | 11 | 8 | 10 | 9 | 16 | 29 | 12 | 5 | 9 | 18 | 12 | 8 | 20 |

| Education and training | 158 | 49 | 115 | 47 | 41 | 53 | 29 | 51 | 108 | 44 | 37 | 65 | 78 | 50 | 19 | 46 |

| Voluntary sector | 60 | 19 | 38 | 16 | 22 | 29 | 9 | 16 | 46 | 19 | 11 | 19 | 23 | 15 | 11 | 27 |

| Environment task force | 71 | 22 | 65 | 27 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 18 | 63 | 26 | 4 | 7 | 37 | 24 | 3 | 7 |

| Had left New Deal Footnotes 1: | 8779 | 100 | 6096 | 100 | 2667 | 100 | 1043 | 100 | 6855 | 100 | 1530 | 100 | 3048 | 100 | 955 | 100 |

| For an unsubsidised job | 3191 | 36 | 2268 | 37 | 916 | 34 | 356 | 34 | 2595 | 38 | 468 | 31 | 1060 | 35 | 421 | 44 |

| For other benefits | 1259 | 14 | 705 | 12 | 554 | 21 | 183 | 18 | 1066 | 16 | 153 | 10 | 463 | 15 | 92 | 10 |

| For other known destination2 | 754 | 9 | 507 | 8 | 246 | 9 | 80 | 8 | 541 | 8 | 165 | 11 | 221 | 7 | 71 | 7 |

| Unknown destination | 3575 | 41 | 2616 | 43 | 951 | 36 | 424 | 41 | 2653 | 39 | 744 | 49 | 1265 | 42 | 358 | 38 |

Footnotes

Footnotes 1 The breakdown of this category is the immediate destination on leaving; the individual's position at the end of the month may have changed. 2 This includes young people, who, on leaving New Deal, continue to claim JSA. Percentages may not add up to 100 due to incomplete data or rounding.Discussion

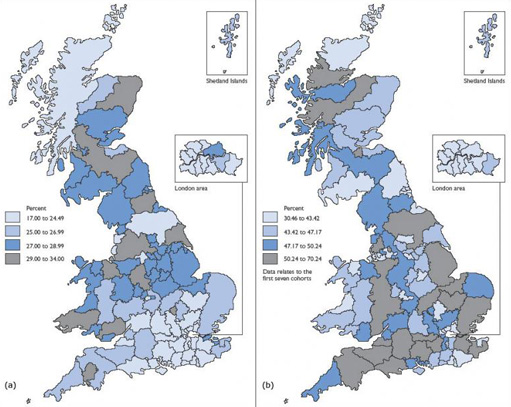

There are clearly some major differences, as well as many areas of similarity, between all the social groups identified regarding which options they follow and what they move on to. Many different explanations might be offered. We will return to the more significant differences and explanations later. What is beyond any doubt, at this stage, is that it is impossible to judge, on the basis of this kind of evidence alone, who refuses to participate and how these patterns reflect differences in personal lives. One possible source of explanation of differences in this data is that employment opportunities for young people differ greatly between different parts of the country. Such variations might help us to understand much better the causes and effects of participation in (and refusal of) welfare-to-work programmes. Sunley et al. (2001) analysed the spatial distribution of unemployment and the success rates of NDYP leavers in securing jobs (see Figures 4 (a) and 4 (b)).

Activity 3

Compare Figures 4 (a) and 4 (b), beginning with a locality that you know well, then look at north-south differences and national differences, and finally compare the largest conurbations with other localities. Make notes on the relationship between high and low levels of youth unemployment, and high and low levels of entry into jobs.

-

Is there a spatial match between the proportions of unemployed and of those gaining jobs after NDYP?

-

If so, is it uniform or variable?

-

If it is variable, is there a difference by region or by size of area?

-

What interpretations come to mind about patterns and variations?

Discussion

There are clearly major differences between localities, and some close correspondences between levels of local youth unemployment and the job successes of leavers. Again, we will return to these points. For now, it is important to note that although this additional evidence offers some important pointers to the significance of patterns of participation and withdrawal, it is by no means sufficient to make sense of them. Other kinds of evidence are needed.

4 An auditor reports

4.1 Looking at the evidence

Some analysis of the data shown in Figures 4 (a) and 4 (b) is needed to set it in a wider context. We need to know how many openings were created after the NDYP was launched, who participates in the programme, and with what outcomes. Not only would this answer questions about the significance of participations and withdrawals, it would allow insights into the rationale for NDYP. A report by the National Audit Office (NAO), The New Deal for Young People (2002), is an authoritative statement to Parliament on the programme's value and cost-effectiveness. The focus of the report is quite specific: is NDYP a good use of public funds and does it contribute to the economy?

Activity 4

Read Extract 1 below and make brief notes on the NAO's assessment of the value and effectiveness of NDYP, on the criteria it employs to come to its conclusion, and on the data that was used.

Extract 1: ‘NAO report on the New Deal for Young People’

How far the New Deal for Young People has met its objectives

5 The government met its target of getting 250,000 under 25-year-olds off benefit and into work before the end of the 1997 to 2002 Parliament in September 2000. By the end of October 2001, some 339,000 participants in the New Deal for Young People had ceased claiming job seekers allowance and had experienced at least one spell in employment, including subsidised employment. Of these, some 244,000 young people had left for sustained unsubsidised jobs. A further 30 per cent of leavers left to unknown destinations. Research indicates that 56 per cent of participants who left the programme and for whom no known destination was recorded (some additional 107,000 young people) had left to go into a job. However, some young people placed into sustained jobs (lasting more than 13 weeks) will have returned to unemployment within that period without reclaiming job seekers allowance.

6 A large majority of the young people placed into sustained jobs remained out of unemployment for a substantial period. However, as might be expected in a dynamic labour market, some young people placed into jobs subsequently returned to a period of unemployment. This is a positive outcome as long as they remain employable, actively seek work and do not return to long-term unemployment …

Impact of the programme on the national economy

8 The New Deal for Young People achieved its stated target of helping 250,000 young people into work in September 2000. But the economic impact of the programme cannot be measured simply in terms of the number of young people placed into jobs. For example, many of them would have found a job anyway because of natural labour market turnover and the general expansion of the economy. The overall impact of the programme therefore needs to be viewed in the context of wider labour market dynamics, as many young people will become unemployed and leave employment without any labour market intervention. Also, the headline figure of the number of young people placed into work does not measure the additional benefit for those who have participated in the programme in terms of their improved longer-term labour market position.

9 Research commissioned by the Employment Service into the first two years of the programme's operation estimated that the New Deal for Young People had reduced youth unemployment by 35,000 and increased youth employment by 15,000.

10 Our analysis suggests that these estimates of the direct effects of the programme were reasonable. Because of inherent difficulties in evaluating the programme, they needed to be placed within a fairly wide range of plausibility, but it is clear that there is a positive effect.

11 The research also estimated that the programme indirectly had increased employment in groups other than 18- to 24-year-olds by 10,000. Based on this research into the direct and indirect effects of the New Deal for Young People, we estimate that national income has grown by a minimum of £200 million a year.

12 The government had spent £668 million on the programme by March 2000. After taking into account the programme's impact on other parts of the government budget, its estimated net cost was around ±140 million a year. Applying this to our estimates of the programme's impact on levels of employment, the average annual cost per additional person of any age in employment lies within the range of £5,000 to £8,000 …

| Effect | Plausible range of estimates |

|---|---|

| Reduced youth unemployment | 25,000–45,000 |

| Increased youth employment | 8,000–20,000 |

Discussion

The NAO's assessment is equivocal. The increase in youth employment is proportionately very small. The report is careful to differentiate new jobs from existing jobs that employers transfer to NDYP in order to gain the subsidy. It expresses concern about the 30 per cent of leavers to unknown destinations, and about the subsequent unemployment of those who get work when they leave. It draws attention to poor provision for those who are ‘harder to help’, and the declining trend in the numbers of leavers beginning jobs that results from the practice of placing the ‘easiest’ recruits first. Finally, while the net cost of £140 million is exceeded by the estimated net growth of £200 million in the national income, the annual cost per trainee of up to £8,000 is several times the cost of the trainees’ ‘allowance’, partly because of the subsidy to employers.

The criteria upon which the report bases its assessments are exclusively quantitative. Aspects of the programme that ‘were not measurable’ are ignored. Questions about how it was experienced by young people and employers are not addressed. There is therefore no measure of ‘value added’ to participants' skills. Nevertheless, the report confirms a number of important points. Few jobs are created and the impact on youth unemployment is relatively modest. There is no saving on welfare costs, but a very small gain in overall economic output. And while there is still a lack of clarity about drop-out, refusal, withdrawal and ineffective outcomes, it seems likely that the 30 per cent who left for unknown destinations were withdrawals before completion. The duration of jobs gained beyond 13 weeks is uncertain. This strongly suggests refusal or resistance alongside a substantial proportion of successful placements.

To interpret these findings, and to consider how New Deal policies constitute a response to and a shaping of personal lives, clear frameworks for interpretation are needed. We begin with two that offer opposing analyses.

4.2 Neo-liberal interpretations of welfare to work

Neo-liberalism begins from an emphasis on the free market, individual freedom and responsibility. Neo-liberal approaches use the ‘less eligibility’ principle. Welfare is thought to distort ‘free’ markets, because it either removes incentives to work, or drives up entry-level pay to rates that are not economical for employers. Neo-liberals tend to advocate what Peck (2001) terms the ‘hard’ Labour Force Attachment model of working for welfare, which places claimants directly into labour markets as a condition of welfare. This is thought to break cycles of dependency by reducing welfare costs and containing wage inflation, following the economic-regulatory rationale. In practice, this model is often conflated with the conservative-inspired social-disciplinary rationale, in which mandatory attachment brings good habits of work. Both facets are visible in Tamarla Owens' experiences in Michigan. ‘Softer’ versions locate the problem in inadequate skills and work experience. This is the Human Capital Development model, based on personal-developmental rationales.

Advocates of the Labour Force Attachment model would argue that NDYP is not a workfare programme. It does not reduce welfare costs, enforce immediate labour market entry, stimulate competition for the lowest paid jobs or even demonstrably help to control wage rates. It is closer to the Human Capital Development model. On its criteria, the NAO's (2002) findings reveal that the programme has succeeded in the core aims of removing large numbers of young people from the unemployed register and obliging them to make themselves employable.

4.3 Neo-Marxist interpretations of welfare to work

Neo-Marxists interpret welfare-to-work programmes as doubly alienating. First, the programmes deny workers control over the conditions of their ‘employment’ by forcibly constructing their relations with employers. Second, they deepen social inequalities because they are concerned with people who are weakest in the competitive labour market. Neo-Marxists view economic regulation as the principle purpose of welfare to work. Its task is to manage the contradictions of the capitalist welfare state (Offe, 1984) by reconciling the tensions between welfare provision and capital accumulation during transformations in work Welfare states are said to be moving away from stable full employment and management of the market economy within a national policy framework (the Keynesian Welfare National State) and towards a regime in which welfare depends on work and competitiveness, requires continuous change in the pursuit of efficiency, and policy decisions are taken in the context of cost-cutting globalised production (the Schumpeterian Workfare Postnational Regime) (Jessop, 2000). The implications of the latter for welfare are that costs too must be minimised, following the ‘less eligibility’ principle. So must the costs of the cheapest labour, if affluent Western welfare regimes are to compete in global markets.

Neo-Marxism, therefore, draws attention to a number of NDYP's shortcomings. The capacity of the programme to create employment is very limited. Costs per ‘trainee’ remain high, so it is not reducing welfare expenditure. There is no audit of enhanced skills. And with large numbers of leavers to unknown destinations, its social-disciplinary value is also in doubt. These criticisms are reinforced by Sunley et al. (2001) in their spatial analysis, which concludes that NDYP may be least effective in the very localities in which it is most needed as the analysis in Figure 4 suggests. And the data in Table 1 for job placements show that it magnifies existing labour market inequalities.

Analyses therefore conclude that economic regulation is the main purpose of such programmes. Grover and Stewart (1999; 2000), for example, argue that the objective of the programmes is to contain wage inflation by drawing into employment inactive people who will accept entry-level wages. Peck and Theodore (2000, p. 120) argue that they ‘intensify competitive pressures at the bottom of the labour market and enforce low paid work’. NDYP adheres to the ‘less eligibility’ principle by shaping the critical ‘reservation wage’: the minimum amount of pay for which employees individually decide they are prepared to work.

Young women are in a 30:70 minority on NDYP (see Table 1). There is now a concentration of women in part-time, lower paid, and generally less skilled work sought by poorly qualified young people. Marxist feminists would explain this in terms of young women's adaptability in labour markets, and their historically lower reservation wage as ‘second earners’ and a ‘reserve army of labour’, which can be called upon in boom times, or when the wage demands of the primary labour force threaten employers' profits.

4.4 Finding ‘the personal’ in policy: responses, refusals and resistances

The reservation wage is one of many meeting points between personal lives and social policies. Personal lives fundamentally condition the rate of pay at which everyone individually decides they can or must work. Policies like New Deal necessarily regulate that level.

Activity 5

Read Extract 2, below, from interviews with three lone mothers who were considering the option of registering for the New Deal for Lone Parents (NDLP), and make a note of how their personal lives shape their responses.

Extract 2

I'm on a career break from my job at – at the moment and working part-time in the local library. I am waiting until my little boy is at full-time school before I return to work. I had a lone parent interview because at the library where I work I was offered 12 hours a week. So I phoned them up to ask about my benefits, how it would affect them. [The Personal Adviser] put all the figures in the box, and it came out that I was going to be worse off. If it had been 16 hours, it would have made a big difference.

…

I had a visit from the lady from the social, and she said to me, ‘I know you are determined to work, but you know is it really worth it, especially when you start talking about childcare and all the different bits and pieces?’ I said to her, ‘It might not be worth it, but I prefer to be out keeping my brain active as opposed to just sitting at home’. Because when I'm at home it's just housework, ironing, cooking and I hate it you know.

…

I'm not a material person, but I think most people would agree that it's not worth putting yourself through all that and being only £20 better-off. I suppose that a majority of single parents would agree with that. What's the point? It's more hassle than it's worth, getting the kids organised, getting them out, getting yourself ready, getting yourself out, getting back. I mean, on top of your work you're coming home, looking after these children, making the tea, bathing them, putting them to bed. You really have to have an incentive, you really have to make it worth your while. I know it's a bad attitude to take, but I really would need to get more than £20 a week extra.

Discussion

The balance of how policy pressures and financial interests meet for these three women is finely poised. For the first, a difference of four hours pay is critical; for the second, the marginal disincentive to work is negligible; for the third the marginal gain is inadequate. The critical allowance thresholds for NDLP are determined politically to strike the balance between incentivising work and avoiding wage inflation. But whether they function as intended is determined by the individual circumstances, beliefs and attitudes of lone parents. There are elements of neo-liberal rational self-interest in all three responses, but how these are expressed is also inflected by personal developmental concerns for the first two women, and by the neo-conservative social disciplinary rationale embraced by the second and resisted by the third.

Participation in NDLP is voluntary. In NDYP it is a condition of welfare. The threat of benefits sanctions gives NDYP some power to shape behaviour. But the examples of Sid's and Jolene's experiences below illustrate how differing individual circumstances radically affect this power:

Sid left his Subsidized Employment Option as a catering assistant in a nursing home because ‘it wasn't really a catering job, it was a skivvy's job’. He thought he would learn how to cook and get some proper catering experience. However, most of the work involved microwaving pre-prepared [sic] food. Sid left the Option knowing he would be sanctioned. However, he knew he could rely on his parents to financially support him during the period of sanction.

…

Jolene undertook a Voluntary Sector Option at a local community centre. After three weeks, she became ill with flu and was out of work for over a week. She had rung her employer on the first day of illness but did not realize she should have done this for every day of the illness. Even though she had a doctor's certificate, she was sanctioned for two weeks. Jolene was upset that she was sanctioned. For the two weeks she found it difficult to survive. She lives on her own and had to borrow money from friends to pay for electricity and food. She also received £2 a day from a crisis fund.

(O'Connor et al., 2001, p. 75)

Evaluation studies report participants leaving under threat of sanctions (O'Connor et al., 2001). This undoubtedly involves adjustments to their personal reservation wage thresholds. It is here that the scope for agency in resisting and evading programmes is greatest, and that refusal of placements shown in Table 1 may reflect determination to dilute the force of policies that shape personal lives. Faced with a Personal Adviser (PA) who is determined to place them regardless of suitable options, some young people leave for stop-gap work. Ritchie (2000) reports that nearly two-thirds of those who leave do so when unwanted placements loom large. Underlying the statistics of early leaving, non-participation and unknown destinations are innumerable stories of planned non-entry, last minute evasions, and multiple re-registrations. They may be dismissed as chaotic manifestations of disorderly lives or they may constitute resistance. Only research about intent and motivation would be able to illuminate this issue further.

Such actions carry particular meaning amongst minority ethnic groups. The evaluation study of NDLP by Dawson et al. (2000) marks a sharp differentiation between the social integration of black non-participants in the programme, all of whom were already involved in work or training, and Bangladeshi women, who were unlikely to participate because of family support networks and commitments to care for their children. A study by Kalra et al. (2001) amongst Bangladeshis and Pakistanis found that many who left after an initial interview with their PA did so to avoid NDYP. Local personal networks accounted for its poor reputation amongst those who described bad placement experiences and negative attitudes towards Asian clients on past programmes.

These studies show how personal lives, constituted through particular racialised identities, respond to the lived experience of programmes, and may include culturally-based forms of collective refusal. Behind these responses and resistances lie narratives of persuasion and attrition, adjustment and submission. PAs will have striven to engage the attention and win the trust of their clients, drawing out their interests, perhaps trying to fashion them to approximate available options. But the outcomes of such encounters are inextricably bound in a complex web of individual histories, circumstances, networks and dispositions that make up the personal lives of clients. Some options may be unappealing, resonate with negative past experiences, or fit badly with firmly held views or cultural mores which clients are not prepared to compromise.

5 Personal Advisers, personal lives

What is clear from a wide range of New Deal evaluations (Dawson et al., 2000; O'Connor et al., 2001; Lewis et al., 2000) is that PAs provide a critical interface between the programme and its clients. The prominence of ‘personal’ in their title carries several meanings. Clients are allocated to PAs on a one-to-one basis, with the implication of a relationship, and of continuity. It also implies personal advice, which crosses the boundary of the informational into the distinctive needs of a particular individual.

The way in which this relationship is realised is a key to understanding how policy and ‘the personal’ meet. Historically, the contact between welfare officials and ‘clients’ has taken different forms; this is revealing about how the relationship is constituted. We explore this next.

Activity 6

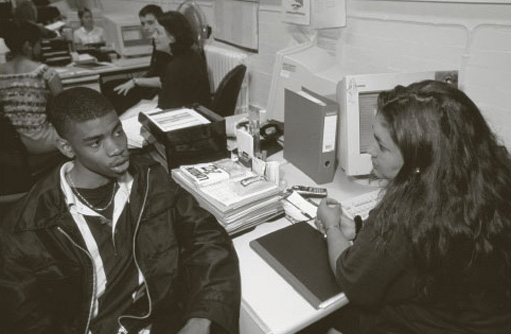

Look at Figures 5 and 6. Pick out any signs that suggest how the relationship between official and client is constituted, inferring what you can from the finer detail.

Discussion

It is clear that these images portray two very different conceptions of how welfare officials and their clients should interact. Figure 5 is archetypal, symbolising millions of similar gendered encounters between a bureaucrat official of the old welfare state, and a waiting line of massed, anonymous claimants. All the participants are male and white. The geography of the room speaks of separation of official from claimant. A counter keeps them safely apart, and the steel framework above it suggests that there are shutters which can be erected when needed. The attire of the various actors too tells of separation: the smart white-collared, besuited official with his plastered hair and studious spectacles facing the mass of flat-caps and uncustomary neck-ties, some hidden under mufflers – all markers of class distinction. Their engagement is impersonal. The gaze of the official and of the applicants alike is downwards. They are concerned with paper records, the symbolic bureaucratic administration of statutory entitlements according to predetermined criteria. The official searches for cards that represent applicants and the applicants testify in writing to their eligibility. No words are spoken at the moment captured in the photograph, and we might imagine verbal exchanges to be brief, structured and predictable. The encounter shown in Figure 5 is an act of regulation.

In Figure 6, there is still little difficulty in distinguishing between the official and the client, but the highly formalised style, attire and geography of their distinct roles is absent. Both participants (and those behind them) are on the same side of the desk, with nothing separating them. The clues about their respective positions are less obvious. The female adviser seems smartly, but informally, dressed. The male client is dressed more casually. Their gendering is typical of their roles: most PAs are women, most NDYP clients are male. Their ‘race’ too reflects the overrepresentation of young black men on the programme. Their encounter has the hallmarks of something genuinely interpersonal – they are holding one another's attention with direct eye contact, and they are there to converse, not read and fill in forms. He speaks, she listens. The PA seems engaged with her client as a unique individual. This is closer to autonomous, personal contact between subjects rather than to the ritualised enactment of roles. It suggests an encounter that might be developmental, rather than regulating or disciplining. Yet one actor (the PA) holds most of the power, symbolised by her computer, with fast access to records, personal details and information about jobs.

The two encounters shown in Figures 5 and 6 symbolise very different ways of understanding – and theorising – how policies and personal lives meet. The first is premised on a coherent, organised state machine in which agents act as part of a chain of command, following a rule-based script in fixed, consistent ways. Such encounters are de-personalised and bureaucratised versions of the social-disciplinary rationale that underpinned the workhouse regime. This reading accords with some ‘orthodox’ Marxist analyses of how the state exercises power through institutions. Few now claim that officials slavishly serve ‘the state’, and there is ample evidence that ‘street-level bureaucrats’ (Lipsky, 1980) variously adjust, adapt, dilute, ignore or even subvert procedures and directives when their discretion dictates. Wright (2003) found clear evidence that job centre staff are strongly influenced by their own beliefs and values, which lead them to categorise clients and deal with them using sharply differentiating moral assessments.

This reading fits the personalised interaction in Figure 6, in which the relative autonomy of both actors is acknowledged. Each speaks not according to a script, but by using their discretion to negotiate an outcome within broad rules, which are open to interpretation, can be ‘worked round’ and cannot prescribe action. If the purpose remains social-disciplinary, the techniques fit the personal-developmental rationale. This interpretation is closer to post-structuralist theories of governmentality. These argue that it is through such encounters that relations of persuasion and power are enacted. Following Foucault's theories about the processes through which people's conduct of themselves is governed, Rose (1999) argues that:

To dominate is to ignore or to attempt to crush the capacity for action of the dominated. But to govern is to recognise the capacity for action and to adjust oneself to it. To govern is to act upon action. This entails trying to understand what mobilises the domains or entities to be governed: to govern one must act upon these forces, instrumentalise them in order to shape actions, processes and outcomes in desired directions. Hence, when it comes to governing human beings, to govern is to presuppose the freedom of the governed. To govern humans is not to crush their capacity to act but to acknowledge it and to utilise it for one's own objectives.

(Rose, 1999, p. 4, emphasis added)

The task of PAs, then, is to find what motivates (or mobilises) their clients, to shape it in ways which can be realised through the programmes on offer (to instrumentalise it), and to induce them into those programmes. Part of this will involve careful listening to individual priorities and preferences. It may also involve persuasion that one activity leads to another more desirable possibility. And part may involve inducing a realistic approach to what is available.

The more difficult these processes of negotiation, compromise and adjustment, the greater will be the need for pressure through establishing norms by means of discourses that assert that welfare is always the product of someone's work, and that it is a matter of personal responsibility to be the provider of one's own welfare by working. As welfare subjects become imbued with this thinking, through their relationship with their PA, they begin to rely less on being governed by the PA's interventions, and begin instead to govern themselves.

Rose (1999) argues that welfare-to-work programmes epitomise the governance of disapproved social behaviour, through moral pressures upon individual conduct. What might once have been treated as social-disciplinary issues are recast as behaviours in need of remoralisation, through which the dominant discourses of PAs get inside the thinking of unemployed people and harness their energies towards making themselves ready for employment. Their clients become party to the belief that they are responsible for their own employment, and that expecting welfare support without work is socially irresponsible. In this way, PAs are charged with reconstituting their clients as responsible, self-governing subjects, and as worker-citizens of enterprising economies. Social-disciplinary purposes are largely masked by personal-developmental practices. And it is in this way that social policies shape personal lives. What is less clear is how far this theory allows that such strategies may fail, in the face of resistance.

Feminist post-structuralists would inflect this interpretation by focusing on the predominance of women in PA roles, who are presumed to use the skills of responsiveness that women develop as daughters, sisters, wives and mothers to negotiate potentially conflicting interests by appreciating the needs of others and accommodating them. It is a key tenet of feminist epistemology and methodology that ‘the personal’, and lived experience, are at the centre of theoretical and empirical work. Feminism often works outward from ‘the personal’ through dilemmas and contradictions towards the policies that frame them, rather than vice versa.

This has profound implications for the kinds of evidence that make it possible to understand how welfare and work are contingent upon one another and the way that personal lives intersect with welfare policies. Such evidence is located in millions of encounters in which welfare subjects are constituted, or resist being constituted, as responsible self-governing worker-citizens. Hence, it is only qualitative studies that can successfully unpack the biographies of personal lives in order to track the power relations of work and welfare. In this case, tables, maps and audits offer little insight into how ‘the personal’ and social policies are mutually constitutive, and how constitution is resisted. This course began with Tamarla Owens' biography, and it is to another that we now turn to advance this argument.

6 A short biography of Mandy: comparing theories about work and welfare

Mandy's biography has some striking parallels with Tamarla Owens', but also some clear differences from it. It comes from an evaluation report on NDYP. Despite its brevity, it illustrates the potential of beginning from ‘the personal’ to show how social policies constitute welfare subjects.

Activity 7

Read Extract 3 below. Write a sentence about how you think neo-liberals, neo-Marxists, governmentality theorists and feminists would make sense of the way in which NDYP policies and Mandy's personal life ‘frame’ one another. Keep in mind the part played by Mandy's PA in the processes involved, and any aspects of Mandy's conduct that represent resistance to the processes of her own constitution as a responsible, self-governing welfare subject. Note too any comparisons and contrasts with Tamarla Owens' story.

Extract 3: ‘Mandy’

Mandy, now aged 21, left home when she was 16 due to a conflict with her family. After a period of sleeping rough, she was temporarily housed in a hostel for young women where she lived for a few years. About a year before starting NDYP, Mandy moved from the hostel into a flat. However, she found it difficult to make the transition to independent living, especially with managing her money and paying for bills.

On joining NYPD, Mandy enrolled in full-time education to gain secretarial skills. However, she found it hard to adjust to being in education again. She also felt that there was no support for her to make this transition. She became disenchanted with the [Education] Option and eventually left after two and a half months. Mandy moved on to Follow-through [the stage of NDYP once clients have been on an Option] where she was sanctioned for not completing her Option. The loss of benefit was very problematic for her, adding to her already mounting debt and her difficulty with managing money. This financial crisis led to her being evicted from her flat. After a short time of sleeping on various friend's [sic] floors, she moved in with her mother temporarily. At the time of interview, she was still there, but acknowledged that the situation was far from ideal. She was worried that if the relationship deteriorated again, she did not have anywhere else to go.

NDYP threatened to take Mandy's personal life to the edge of crisis. She was clearly already extremely vulnerable, and young women who ‘sleep rough’ easily fall prey to sexual exploitation. Mandy's admission to a hostel suggests this was recognised. However, once she was subject to NDYP this recognition apparently lapsed. She joined a course for which she was ill-prepared, perhaps under pressure from her PA. The withdrawal of her allowance as a sanction for leaving the Education Option (normally at a PA's discretion) presumably caused her to spend her housing benefit on immediate essentials, leading to rent arrears and eviction. This clearly upset a delicate balance that had begun to move her from vulnerability towards independence. In an attempt to hurry her progress, NDYP returned Mandy to the circumstances that put her on the streets.

From a neo-liberal interpretation, paradoxically, Mandy's history epitomises the benefits of welfare to work. It is because there are sanctions with painful consequences that NDYP promises success. Aged 16, Mandy was a dependent who had her own flat – a ‘perverse incentive’ her peers might envy and emulate. NDYP removed the artificial protection of unconditional welfare and exposed Mandy to work and the costs of independence. Her return to her mother's home would help her realise that it was rash to leave the course and lose the flat. The shock of the sanction is the PA's ‘tough love’ that should break Mandy's dependency. It is likely to have pushed her into low-paid work (meeting the economic-regulatory purpose) or study (meeting the personal-developmental purpose), and promised to discipline a supposedly disorderly life.

A neo-Marxist analysis takes a very different starting-point. Once she left home, Mandy had no means of subsistence. By making welfare conditional upon work, NDYP again put Mandy at risk of the depredations of street life. She was an exploited victim of an inequitable system whose economic relations either drive people like Mandy directly into low-paid work or require them to gain skills that later bind them to it. Her brief engagement with NDYP would probably have lowered her reservation wage. She was also apparently pushed towards a course for which she was not ready.

A job placement would have helped more with her debt problems. But as we saw, paradoxically, NDYP is least able to provide jobs where they are most needed. By initiating the sanction, Mandy's PA acted as a rule-following state agent, who seemingly had little regard for the counterproductive consequences of her actions. By triggering Mandy's eviction from her flat, the sanction escalated an understandable act of resistance into a personal crisis, returning her to live with her ‘estranged’ mother. This is characteristic of the contradictions of state welfare. In an effort to make welfare conditional on work for reasons of social discipline or economic regulation, vulnerable people are precipitated into the very crises that make the most costly demands on welfare.

Post-structuralist analyses offer differing readings of Mandy's experience. In a Foucauldian reading, the discourses of welfare to work employed by her PA have, in this case, been unable to move Mandy to inhabit the subject position of a working welfare-recipient, en route to becoming a self-governing, responsible worker-citizen. Her ‘personal’ has prompted her to refuse to be constituted in this way, because the discourses have not been able to override her dislike of the college course, or her problematic relationship with her mother. Though it may have been neither deliberate nor conscious, Mandy resisted the dominant discourses.

A reading based on post-structuralist theories of governmentality interprets Mandy's experiences differently. It sees the crisis that follows the withdrawal of her benefits as one episode in a continuing history of welfare interventions. In different ways, each intervention is part of a process of acting on Mandy's own autonomy as an actor – that is, of enabling Mandy to govern herself more effectively. The allocation of her own flat presupposed her freedom to shape her own life. Her PA will have worked to establish her interests, acknowledged her capacity to be responsible and aimed for the best match with placement options. This time, the intervention failed. As an autonomous agent, Mandy chose to quit the course. She may have done so in the knowledge that she would be sanctioned, but it is far from certain that she knew that this in turn would result in eviction. The programme governs its subjects through persuasion, but also through more coercive measures by withdrawing benefits. Mandy is being induced to govern herself both through steering by her PA, and by being put under financial pressure. Though this episode did not induce Mandy to govern herself in the way envisaged, it may be that she has learned the price of refusing ‘guidance’, and (as neo-liberals would also suggest) would act differently on a future occasion, out of self-interest.

Feminist analysis would emphasise Mandy's vulnerabilities as a very young woman, especially to male sexual exploitation and unwanted pregnancy. It would take up the hints that Mandy's mother is a lone parent, for whom bringing up a teenager may have been stressful. It would point out that the effects of treating families as the back-stop when welfare is withheld impact almost entirely on women. Marxist-feminists would see the actions of Mandy's PA as reproducing a gender-differentiated dual labour market, by steering her towards secretarial work and a subordinated labour market position. Post-structuralist feminists would draw attention to the absence from the account of Mandy's voice, and her mother's, and of details of their relationship. They would also remind us that we know nothing of her PA's working life in which she juggled the tensions between discipline and development, and between her own responses to Mandy and formal NDYP requirements. Without this information, interpretation is speculative.

7 Workfare lives: evaluating theories

7.1 Introduction

The theoretical interpretations in Section 6 of how NDYP ‘met’ Mandy's life offer important insights, but none provides a definitive interpretation – and all require evaluation that looks critically at their epistemological bases, internal coherence, resilience to contrary evidence and robustness against other theoretical positions. In this section, we can embark only on the briefest of evaluations, by taking the starting-points of each theory in turn and offering a critical voice from other theories.

7.2 The importance of the market and the state: neo-liberalism and neo-Marxism

To begin with neo-liberalism, it is a key premise that the market is the primary means of coordinating economic activity, including the allocation of people to jobs. This assumes that rational actors make judgements about their earnings prospects to decide their best options – training to improve employability, as in Mandy's case, or accepting subsistence-level earnings, as Tamarla Owens did. To neo-liberals, both Mandy and Tamarla Owens would have used information they gleaned in their everyday lives to make such decisions.

But other theories take issue with the neo-liberal model of the market as a self-regulating set of relations. Post-structuralists point to the innumerable human interventions needed to match workers to places in workfare programmes. When workers are as inexperienced as Tamarla Owens and Mandy, they learn to govern themselves responsibly only through the help of welfare para-professionals. Mandy had to be induced into recognising her need for a qualification; Tamarla Owens had to be led to see for herself the ‘need’ to make a long, inconvenient daily journey. Neither rational self-interest nor direct force alone could mobilise them. The two had to be brought together and explained, and then reworked through Mandy's and Tamarla Owens' own processes of reasoning, of their own volition. And in Mandy's case the intervention was not successful, albeit for different reasons from the failure of intervention in Tamarla Owens' case. Evidence of the critical processes through which personal lives individually embrace, accommodate or refuse the requirements of workfare programmes is visible only in the moments in which para-professionals ‘act upon action’, and ‘instrumentalise’ the self-interest of the governed, in pursuit of the objectives of those who govern.

Alternatively, we can take neo-Marxism as a starting-point. Here, the stress is on the economic-regulatory purposes of programmes that would see Mandy and Tamarla Owens as unskilled workers who are being prepared for their place in the labour market. It is typical that Mandy as a white woman is steered towards the skilled role of secretary, and Tamarla Owens as a black woman towards the low-skill role of waitress. Mandy refuses this role and makes herself vulnerable. Tamarla Owens conforms and excels but remains financially insecure, while her employer's profits rise on the surplus generated from her poverty pay. Both women end up homeless. For neo-Marxists, this is the work of a relatively autonomous state and its agents. Despite its contradictory position on welfare, the state generally works to the advantage of capital, in this case by depressing the pay of the poorest, so keeping welfare ‘less eligible’. In doing so, workfare programmes assure a continuing supply of appropriately prepared labour that can rise and fall roughly in harmony with the economic cycles of growth and retrenchment.

But to neo-liberals, such action by the state is inconceivable: it is the market that coordinates the allocation to jobs and sets wage levels. Mandy is poor because she left home without a job or the skills to gain one. Tamarla Owens is poor because she had children without a partner or a job. They have been exposed to the harsher effects of competitive markets. If markets are to be the engine of enterprise and reward for individual effort, it is inevitable that they produce dramatically unequal outcomes. In time, these two women's skills will accumulate more marketable value if they choose to develop them. Questions may remain only about why poverty is reproduced so consistently in the same families and social groupings. To most neo-liberals (and all neo-conservatives) the answers reside in essentialised differences in the aptitudes and energies of individuals and groups. To post-structuralists, they reside in how such essentialisms are constructed discursively and ‘realised’ in specific local conditions of personal poverty or personal advancement.

7.3 The importance of the individual and gender: post-structuralism and feminism

Reversing the argument, we can begin from post-structuralist theories of governmentality. We might put the case that it is those who ‘act on the actions of others’ at ground level who shape personal lives and govern the social world. It is only through interactions between unique individual client-subjects and PAs' wide discretion that this can occur under workfare arrangements. To neo-Marxists and Marxist feminists, though, PAs are at best semi-autonomous agents of the state, whose power to govern is merely ‘lent’, within prescribed parameters. Discretion may be exercised, and agents may sometimes break rules undetected, but workfare drives most clients into work primarily because those who refuse lose their income. It was the implicit threat of sanctions that made Mandy sign up for the course, and their application by a dutiful PA that made her homeless. The same threat drove Tamarla Owens onto the bus every day despite the needs of her son. The threats may have been unspoken by the PA, but they were nonetheless embodied in state power, which was enacted by Mandy's PA when she stopped her allowance.

On this reading, a post-structuralist theory of governmentality is misleading in its claim that the freedom of the governed is taken for granted and that coercion is not used. So long as coercion exists as a last resort, all interactions take place in its shadow. Rose's (1990, 1999) acknowledgement of the freedom of human beings to act and his reading of the ways in which it is harnessed by para-professionals only makes sense if coercive powers linger as threats. His theory then falls prey to the same criticisms as are levelled at some Marxist theories: the state is wrongly attributed with overwhelming, deterministic powers, whereas there is clear evidence that these are evaded and resisted by the street-level bureaucrats mentioned earlier, among others.

In the face of these arguments, Foucauldian post-structuralist theories seem more persuasive. Individuals are led towards inhabiting particular subject positions through the powers of discourses, but are also able to resist becoming constituted as subjects. But, in turn, this version of post-structuralism is criticised for being impermeable to empirical verification. The processes whereby subjects become constituted are buried in protracted interactions and recurrent episodes of incremental persuasion and attrition. Every case is unique and so cannot provide a basis for generalisation. And the interactions that underlie them require insights into the psychodynamics, cognitions and changed beliefs and morals of newly constituted subjects. The key issue, as always, is one of interpretation.

From another theoretical position, feminists have pointed to the gendered nature of the way in which workfare has ‘made’ personal lives, either through women's distinctive position in the labour market, or through particular subjectivities available to women without work. The allocation of Mandy and Tamarla Owens to stereotypically gendered activities (as secretarial student and waitress) underlines the tendency of workfare schemes to reinforce old inequalities. Both women are single; both their lives are framed by lone parenthood – Mandy as daughter, Tamarla Owens as mother. And both suffer poverty that has made them homeless in troubling circumstances. In this sense they represent the condition of many whose financial position as single women is precarious. The challenge to feminism is to analyse how gender is cross-cut by other sources of inequality in the ways policies shape personal lives. To Marxist feminists, it is the combination of their class and gender that unite Mandy's and Tamarla Owens' experiences. Tamarla Owens' experience as a black person deepens her disadvantage, but does not qualitatively alter it.