Rights and justice in international relations

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 20 April 2024, 7:28 AM

Rights and justice in international relations

Introduction

This course is about rights and rights claims, and the idea of implementing justice in the international sphere based on the concept of rights. It is agreed by most people that ‘rights are a good thing’ and in many respects they are. However, this course deliberately takes a critical view. It seeks to examine closely why rights are a good thing and highlights some of the problems associated with rights. In this way, we hope that the sense in which rights are still, ultimately, ‘a good thing’ can be clarified and sharpened, and the valid reasons for rights thereby strengthened. The belief in rights based on a moral assertion of a common humanity that we all share is not self-justifying, and it needs to be located within the complex political field of international relations.

In Section 2, we look briefly at some aspects of the development of internationally recognised human rights as expressed in the UN Charter and 1948 Declaration. Section 3 and Section 4 consider rights and justice by elucidating the meaning of the terms and some of the debates about how best to conceptualise them. In Section 5 and Section 6, the working definitions previously outlined are used to think about the impact that notions of rights and justice can have on international relations. In the concluding section (Section 7), we consider the future of rights and justice in the international realm.

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course DU301 A world of whose making?.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

understand the different interpretations of internationally recognised notions of rights and justice

give examples of implementing justice in an international sphere

investigate questions in international studies

analyse the different agencies of change in the international system.

1 International human rights: an introduction

There are many examples of claims for rights in the international sphere.

One example was reported in September 2002. The British government was asked to make efforts to have a British man held by the Americans at Guantanamo Bay deported to Britain to face charges of terrorism there in connection with the attacks on 11 September 2001. Concerns were expressed about the denial of this man's human rights at Guantanamo Bay. Are alleged terrorists entitled to human rights? Can the denial of their human rights be justified on any grounds?

Another example, from around the same time, concerned a woman in Nigeria who faced death by stoning, once she had weaned her baby, after being convicted of adultery. In another case a teenage single mother was given 100 lashes for adultery, even though she claimed that she had been raped by three men. The court ruling in this case said that the woman ‘could not prove that the men forced her to have sex’ (The Guardian, 20 August 2002).

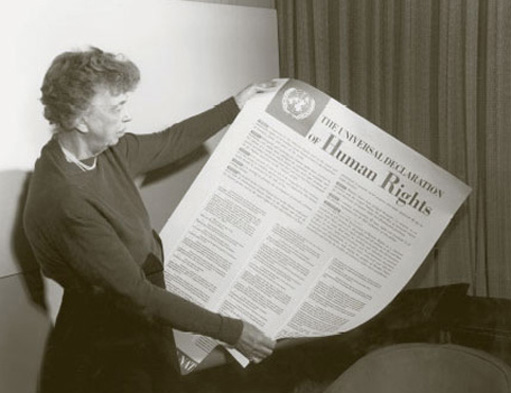

We can hardly imagine the novelty of the idea of universal human rights embodied in the Charter of the United Nations and subsequently codified in the United Nations’ (UN) Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948. A radical change occurred in the vocabulary of international politics with the adoption of the Charter, the 1948 Declaration, and later conventions clarifying and extending the notion of human rights. The UN Charter (including the 1948 Declaration) was an important part of the international post-war settlement and it established the UN as an organisation devoted to peace and security alongside human rights and the rule of law. So many states have joined the UN, and signed its Declaration and later conventions, that this has had the effect of consolidating the concept of rights, both the right of peoples to national self-determination and individual human rights.

The 1948 Declaration, in particular, establishes a powerful moral claim for individual rights. It asserts that each individual matters, deserves to be heard, and must not be silenced. Each individual deserves respect and is entitled to be treated with dignity, regardless of their race, gender, creed, colour or mental capacity. The Declaration utilises a common, universal moral language to specify its principles and norms, and signatory countries have come under pressure to implement those rights. Once codified and interpreted, rights become normative.

At the same time, the Charter expresses the intention to recognise the right to national self-determination and the corresponding principle of sovereign equality among the different peoples of the world. Indeed, the ideas of ‘rights’ and ‘culture’ are closely linked in that the advocacy of individual human rights is tied to the notion of the right to ‘self-determination’ for peoples and to statehood for national cultures. The political identity of a national community is an important part of its culture, but different groups in society perceive it differently, depending on their wealth, social position, cultural background, gender, geographical position and age. Furthermore, different national cultures have different political identities. The language of rights and justice is one of the commonest ways of articulating political disputes, and of negotiating rival claims. In short, claims and counterclaims to rights (and justice) take place within national and now international cultural communities.

2 The United Nations settlement

2.1 Background to the idea of international rights

The UN Charter and the Declaration form part of a post-Second World War international settlement which established, on the one side, the formal legitimating ideology of the international system, national self-determination and sovereign equality and, on the other, the ideology of universal human rights. The appeal of this set of claims was the hope that different peoples could live together in peace and security. It was an attempt to accommodate difference (through the idea of national self-determination) within a common framework (of the sovereign equality of states and universal human rights). The UN Declaration also helped to foster a new understanding of the international order, that is, of the power politics of nation states tempered by a rights agenda. One of the things that lay behind this development was the distinctive view of an international order governed by justice. Rather than being based on competing national self-interests or another moral value such as charity, rights advocates contended that international relations should be conducted on the basis of principles of justice.

2.1.1 Where did the attempt to define notions of rights internationally come from?

To some extent, this ideology of rights was new because it was expressed at the international level with new vigour, with the horrors of the Second World War and the calculated extermination of Jews, gypsies and others in mind. The discourse of individual rights had a stronger impact on international politics than at any time previously, as did the notion of a right to national self-determination. Yet this new departure for international politics also built upon ideas about rights that had been around for a long time in thinking about the relation between individuals and the state. I shall concentrate here on human rights applied to individuals, rather than on the national right to self-determination.

The Congress of Vienna of 1815 had contained an obligation on states to abolish the slave trade, which represented a major attempt at international humanitarianism and standard setting. The 1907 Hague Conventions and 1926 Geneva Conventions attempted to regulate the humanitarian conduct of war. Nonetheless, at that time such measures were understood as framed by the principle and norm of state sovereignty, and were tempered by exclusionary Western beliefs about ‘standards of civilisation’. After the horrors of the First World War, there was a move to institutionalise international co-operation in the League of Nations. Although the League of Nations, inspired by UK and US liberal internationalists, had ‘no explicit human rights provision, the underlying assumption was that its members would be states governed by the rule of law and respecting individual rights’ (Brown, 2001, p. 606).

After the Second World War, the Universal Declaration was adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations (10 December 1948 – now known as World Human Rights Day), with no votes against and seven abstentions (the Soviet Union and its allies, South Africa and Saudi Arabia). Subsequently, all but Saudi Arabia have adopted the Declaration.

2.2 The origins of a rights discourse

In some form, the ideas of ‘rights’ and ‘justice’ could probably be found in all societies and cultures. They are moral concepts because they are concerned with moral ideals; with how things should be rather than describing how things are. However, the notion of rights now has a prominence in political debate in a way it has not had in other times and places. In the political thought of the ancient world, for example, a key question was how individuals could best contribute to the sound running of the political community, with the accent on their obligations rather than their rights. In medieval Europe, a person's place in the social hierarchy was of key importance, and different sets of specific rights and responsibilities were assigned to each level on the scale.

Nevertheless, the medieval concept of natural law from which the modern, international human rights culture derives, specified that in principle all persons were subject to natural law and could understand its content and standards . The conception of rights which grew up in the modern period is concerned with equal rights. This is a very important point. By equal rights, I mean those that specify equality between persons, rights which say that no person should be treated as inferior, or excluded, marginalised, discriminated against, or made ‘other’ or abject. A society upholding equality of rights implies a sense of reciprocity in social relations and interaction, of ‘do unto others as you would have done unto you’. Moreover, the modern notion of rights, based on claims to equality of rights and treatment, contain potentially emancipatory appeals to progressive political campaigning and action, which can imply the disruption of settled social relations within a community.

The modern rights movement has its origins in two separate sources – the tradition of ideas and political theory of the late eighteenth century, and the social reform movements of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Milestones of the first source include the development of the modern view of rights established with the popularity of the American Bill of Rights in 1791 and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in 1789. Works like Thomas Paine's Rights of Man (first published in 1791) were also important in spreading Enlightenment notions of human rights and freedom from hierarchical forms of authority such as the church. Through such means – that is, the juridical codification of rights in state law – the nation state became the body authorised to enact and protect rights.

The move from constitutionally protected rights within a few states to the establishment of the modern notion of rights as articulated in the UN's Declaration was crucially significant. This move has increased the visibility and legitimacy of rights claims within any particular state. It has also had a powerful effect on international politics and law by setting standards or norms of conduct and treatment. In both ways, it has fostered the momentum for social change.

In addition to legal charters and political theory, the modern rights movement is also grounded in a second source – modern social movements. For instance, the anti-slavery campaigns of the nineteenth century argued that the customary pattern of human relationships was unacceptable on the basis of a religious argument about the divine origin of the human body. Subsequent campaigns for the equal rights of women, civil rights (anti-segregation, anti-apartheid) movements, and non-government organisations (NGOs) like Amnesty International have employed arguments about self-possession and self-ownership as well as an argument for communal relational responsibility and interdependence as part of freedom.

These groups have also used the liberal argument for the autonomy of the rational individual to pursue their rights claims. They have, in the words of an anti-colonial discourse, ‘used the master's tools to dismantle the master's house’. In this way, such campaigning groups use the language of the powerful to demand access to those same rights, and call the powerful to account for their easy statements of equal rights.

3 Defining rights

3.1 Introduction

As this history might suggest, defining and conceptualising rights is not straightforward. This section aims to provide a working definition of ‘rights’ and introduce some important debates about rights. It aims to supply some conceptual tools to use when the discussion moves to the sphere of international politics.

3.2 What are rights?

The modern discourse of universal human rights has a number of features. The idea that everyone, everywhere has rights refers to the concept that there are certain entitlements justifiably owed to all individuals by virtue of certain features that all human beings have in common. As the nineteenth-century French politician and historian Alexis de Tocqueville put it, the idea of rights ‘removes from any request its supplicant character, and places the one who claims it on the same level as the one who grants it’.

Rights: a definition

A right is a justifiable entitlement to something (the object of the right), by virtue of the possession of a relevant attribute, against an agent or agents with the corresponding obligation to meet that entitlement.

The justification for (universal) human rights is essentially twofold:

First, the ground for a basic moral equality among people is identified. This may differ from one formulation to another, but all refer to some notion of a shared human capacity for moral agency, and to the idea that such agents should not be treated merely as ends.

Second, human rights specify the general preconditions for exercising moral agency over a lifetime. These preconditions have been variously described – physical security, material means of subsistence, development of capacities, enjoyment of liberties, and so forth. These necessary preconditions for the exercise of moral agency form the basis of human rights. The idea of human rights is designed to advance core values associated with basic needs, interests and liberties relating to what it is to be human and live a human life.

Rights are claims to something, say, ‘to life, liberty and security of person’ (Article 3 of the UN's Universal Declaration of Human Rights) and as such presuppose corresponding duties or obligations on the part of others if they are to be effectively realised. Henry Shue (1980) has argued that there are, in fact, different kinds of duties which are needed to make rights claims effective. There is a duty of avoidance, to avoid depriving people of some necessary precondition for exercising moral agency; a duty of protection, to protect people from such deprivation; and a duty of aid, to assist people who have been so deprived. Individuals and states can owe such duties, and they can be assigned in more or less general or specific terms. Thus, individuals may have a general duty to avoid depriving others, specific duties to some (parents to children, for example), while the state may have a general duty to protect and to aid.

Therefore, universal rights do not presuppose universal duties; there can be a division of labour on the side of duties. For instance, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights recognises that ‘it is governments that have the overarching duty to ensure a division of labour in the matter of positive duties, and one that is appropriate to their own societies and sufficient to ensure that the rights are effectively secured’ (Beetham, 1999, p. 128).

In the modern world, rights claims are most often made against other individuals and against the political community comprising those individuals, that is, against the state. Now, while the state can be seen as a powerfully benign institution in acting to protect, enable and indeed to foster rights claims, the idea of moral rights also defines the fundamental inviolability of persons who need to be protected against state interference. So, the state can be seen in two, contradictory, guises – as both the protector of rights and as the body claiming to override individual rights.

3.3 Examples of rights

Many things have been claimed as rights, as can be seen in the text of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Table 1. One set of rights is citizenship rights. Primarily concerned with basic constitutional issues, these rights should, in Dworkin's phrase, ‘trump’ other considerations such as political expediency and policy-making imperatives (Dworkin, 1984). They are often categorised into legal, civil and political rights. Legal rights include such things as: due process of law; equal treatment under the law; and the right to a fair trial. The right to own property (individually or in association) and the right to enter into binding contracts are also important legal rights.

Examples of civil rights are free speech, free association and free movement. Political rights concern the right to participate in the community's self-government, and in democracies might include the right to vote, to stand as a political candidate, to fair elections, and to a secret ballot. Related to citizenship rights are things like employment rights, for instance, the right to join a union or to go on strike. If rights presuppose duties, and if moral rights presuppose the legal order of a state for their protection, a citizenship right such as the right to a fair trial may express the basic right to life. Likewise, freedom from torture can be defined as a basic moral right (to life, security of person) and as a civil right in a given legal system.

| Of the 30 Articles in the Declaration, the first two set out that ‘[a]ll human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights’ and are ‘endowed with reason and conscience’, and that ‘[e]veryone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms’ set out, ‘without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status’. |

| Articles 3–5 set out the rights to life and liberty, and against slavery or servitude, torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment. |

| Articles 6–12 lay down legal rights, to be recognised ‘as a person before the law’ and equality before the law, against arbitrary arrest, to be presumed innocent until proven guilty, privacy and protection against attack. |

| Articles 13–15 concern the right to freedom of movement within one's country and freedom to leave it, the right to seek asylum, and the right to a nationality. |

| Articles 16 and 17 establish the right to marry and have a family, and to own property. |

| Articles 18 and 19 enjoin the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion, and to freedom of opinion and expression. |

| Articles 20 and 21 establish a right to peaceful assembly, and the right to take part in the government of his [sic] country, such that the ‘will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government’. |

| Articles 22 and 23 prescribe a right to social security, the right to work, equal pay for equal work, and the right to join a trade union. |

| Articles 24–27 dictate rights to rest and leisure, to a ‘standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family’ [sic], to education, and to participate freely in cultural life. |

| Article 28 specifies a right to a social and international order in which these rights and freedoms can be fully realised, while Article 29 commands a duty on the part of the rights holder to the community in which the development of his [sic] personality is possible. |

As you can see, these rights cover a broad range of what we described earlier as basic, citizenship, and social and economic rights.

3.4 Debates about rights

There are at least four big debates about modern individual rights. The aim in putting these before you is to introduce these hotly contested issues to which there are no conclusive answers, but which help frame discussions about human rights. Considering these debates is designed to help you weigh up the different arguments and form your own opinions about the meaning and effectiveness of rights claims.

The first debate concerns how our rights are grounded. One view is that our rights as individuals are natural, that is, basic and human rights which transcend any country or culture we live in, accord with our moral intuitions, and are ‘inalienable’ or cannot be legitimately taken away. The outline of the thinking behind modern human rights discourse discussed in Section 3.2 is often presented in these terms. The opposing view holds that our rights are always cultural – whether they come from a religious source, from an explicit or tacit social contract, or simply from the social practices and traditions that have evolved in a specific community. In other words, do rights reflect a natural order that lies behind the shifting appearance of all contemporary societies, somehow prior to any particular social and political organisation? Or do they depend only upon their meaningfulness within a culture? Do rights claims provide their own transcultural justification or do they only make sense in terms of the justification given in the particular society we live in and as established in its legal norms?

The second debate centres on whether legal, civil and political rights need to be underpinned by social and economic rights in order to be effective. This is the belief that we can only fully enjoy our legal, civil and political rights if we have equal opportunity on the basis of a right to education, a right to work, a right to decent housing, a right to health care, and a right to welfare. Those against accepting social and economic rights as having the same status as ‘basic’ rights, make the case that rights are principles which do not involve costs. So-called social and economic rights are not rights at all, they say, for such things involve huge costs by governments, while legal, civil and political rights are cost-free. An example of this view is that it costs nothing to have a right to free speech.

Question

Looking back to Section 3.2 at the kinds of duties which Henry Shue considered are needed to make rights claims effective, how do you think he might reply to this argument?

Discussion

Those in favour of social and economic rights (sometimes called positive rights) as the basis of legal, civil and political rights (sometimes called negative rights because they are freedoms from various kinds of unwarranted intervention) argue that no such sharp distinction between the two types of rights can be maintained. They claim that even negative rights involve costs to protect and enforce them, such as a police force, a prison service and a judicial system. At this level, the key distinction would appear to be ‘not between different categories of right, but between different types of duty necessary for their protection’ (Beetham, 1999, p. 126). On this basis, writers like Amartya Sen (1999) and Martha Nussbaum argue that a certain minimum quality of life is required in order for individuals to be able to exercise their human capabilities (Nussbaum and Sen, 1993).

The third debate centres upon whether it is sensible to talk about group rights as well as individual rights. Some rights, such as the right to marry and the right to have children, can only be exercised collaboratively, and some rights are relational, for example, the right of a child to be parented. Yet these are still, essentially, rights held by individuals. The argument for group-specific rights, developed by writers like Iris Marion Young (1990), is that the rights of minorities and other self-identified groups on the basis of a shared characteristic need to be explicitly protected. In one sense, of course, this is not a new idea, since the right to national self-determination – that is, a group right for a people to govern itself – is widely and generally accepted. Group-differentiated rights, however, typically refer to groups within or sometimes across a political community, and are advocated so that the interests of the majority do not override those of the minority. Furthermore, without the right (for instance, to exemption from a dress code associated with a particular profession, or to the slaughter of animals for food in a certain manner), it is held that a form of injustice important to group members would occur. The hard cases arise when the claims of the group (for example, to educate its children in a particular language) conflict with the freely chosen claims of some of its individual members.

Group rights claims might involve important practical issues such as special forms of political representation (to empower participation in democratic politics), education rights or language rights. For instance, James Tully's (1995) important discussion of group rights in Canada analyses the claims of English- and French-speaking Canadians as well as first-nation Canadians. Another example is land rights claims in the post-colonial period, promoting the status and rights of groups such as native Americans, Australian Aborigines, and the New Zealand Maoris.

The fourth debate concerns how far the stretching of rights claims can go. Can they be expanded indefinitely? To illustrate, there is a move in the USA to assert the rights of those allergic to deodorants, shampoos and perfumes to a public world in which these substances are banned for us all. A further instance is whether sales of military arms could be challenged on the grounds that arms sales will result in human rights violations. Does an infinite expansion devalue the currency of rights? Possible areas for the growth of rights claims in the current climate include the rights of future generations, the environment, animals and cyborgs.

Question

Do you think we are likely to take these new kinds of rights more seriously in the future?

Discussion

Relevant to this question is whether, in order to qualify for a right, one needs to have not only an interest, but also the potential for articulating and claiming that interest, and for ordering conflicting desires. On these grounds, future generations, the environment, animals and cyborgs would not qualify. Moreover, as we noted above, it is said that only a moral agent (defined as someone capable of recognising a moral duty) can have a moral right. If this is so, might it be that future generations have a narrow legal right rather than a fundamental human moral right? And what about the rights of children and those with severe mental disorders?

This line of thought leads to the argument against the arbitrary and endless proliferation of rights claims. Such endless proliferation, critics maintain, reduces all moral talk to rights claims, which takes away the specialness of rights claims and the impact they can have. Furthermore, according to this view, we all have our own definitions of what is valuable to us and this ‘value pluralism’, a central principle of liberalism, should be encouraged. However, these values should not be translated into rights and imposed by the state on everyone; the state should not be in the business of promoting particular goals for its citizens. We should accept that value pluralism is inevitably going to lead to conflicts, and that if all values are translated into rights, rights will conflict as well. We have a right to hold different values as important, a right to value pluralism.

In addition, critics argue, the language of rights creates a social atmosphere of grievances and victims. ‘Rights talk’ polarises disagreement within national contexts. For instance, the right to life in the USA is claimed both by those in favour of abortion rights in terms of women's rights to choose and women's health, and by those in favour of foetal rights and against abortion. This perspective maintains that ‘rights talk’ also encourages a legalistic view. It transforms moral, social, cultural and political matters into legal ones, and misdirects people to the courts to seek redress.

4 Defining justice

4.1 Distributive and commutative justice

Justice is commonly thought to have two applications which Aristotle distinguished as ‘distributive’ and ‘commutative’ justice. The first, distributive justice, is concerned with the distributions of things (rights, goods, services and so on) among a class of individuals.

What is distributive justice?

A principle of distributive justice specifies how things such as rights, goods and well-being should be distributed among a class of people.

The root idea of distributive justice, according to Aristotle, is that of ‘treating equals equally’. Nevertheless, it is far from simple to specify what this means. Who are the relevant equals? The members of this class might be the individuals of a given political community, the many political communities that make up the world, or even all the individuals in the world. And what is involved in treating people equally? That they all have the same rights, that they all achieve a minimum standard of living?

The second form of justice, commutative justice, is about the treatment of an individual in a particular transaction – it is about giving someone what he or she deserves or has a right to. According to Plato, it is about giving each person their due. An example, often referred to as retributive justice, might be the redress someone is due for a wrong suffered, or the punishment due for an offence committed. Notions of desert and of what people have a right to are also complicated.

What is commutative justice?

A principle of commutative justice specifies how individuals should be treated in a given class of actions and transactions.

Thus, like ‘rights’, the term ‘justice’ is a ‘contested concept’, one whose meaning is never completely fixed or finally closed and agreed upon. This contestability and flexibility of outcome is what Aristotle referred to when he said that ‘justice is the mean (middle) point between conflicting claims’. This view believes that each society (or group within it) will have its own definition of justice and rights, and those definitions cannot (and perhaps should not) be reconciled. Each society (or group) will have its own ideas about justice and rights, and its own practices for implementing them. Such concepts are inevitably conflictual, contestable and politically charged.

Consequently, as a matter of retributive justice, for example, the legal system in the UK no longer upholds capital punishment, but it is an important part of the legal codes of a range of US states. Another instance from the sphere of distributive justice is that liberal societies (which hold that, in principle, maximising the scope of individual freedom takes priority over developing and politically implementing a shared view of the good life of the community) take the view that justice involves allowing individuals to have the largest possible amount of freedom so that they have the widest scope for their own choices.

By contrast, some societies with different cultural and political traditions see distributive justice in terms of the needs of the collective body of members, thereby tempering individual rights. For instance, free speech is a valued right in the American Constitution, but the prohibition to deny the Holocaust in Germany is important to the political identity of that country.

It is part of the contestability of concepts such as justice and rights that the definitions of these terms shift over time, and the process by which this change occurs involves a debate between different normative (value-laden) positions. Therefore, capital punishment used to be practised in the UK as an important form of retribution, and although a majority of UK citizens still support capital punishment, it is no longer held by Parliament to be morally justifiable and does not form part of the legal code. A further example of reforms in rights and justice under the impact of changing social values is a much stronger emphasis on the idea of children's rights than there was even 20 years ago.

‘Justice’, then, is a term that refers to society and its political arrangements as a whole. One way of describing the relation between rights and justice is to say that rights recognise everyone as, in a fundamental sense, the same, whereas justice accommodates the fact that we, while living together, are all different.

Question

How do you think a ‘just society’ differs from one in which everyone is treated in exactly the same way?

Discussion

A ‘just society’ is one that deals fairly with all its members. This does not necessarily have to indicate that it treats them all in exactly the same way. This is what Plato meant when he argued that ‘justice is giving each person their due’, and what Aristotle implied by saying that distributive justice involves ‘treating equals equally’ and commutative justice involves giving people what they deserve. Plato had in mind a hierarchical society in which the benefits and responsibilities were distributed depending on one's position. Bentham's utilitarian model is another influential idea about justice. Bentham, considering that justice refers to society as a whole, argued that it was the function of government to maximize the interests of all (adding up those of each person) by promoting the general good or utility of all.

Like rights, any particular idea of justice (even the idea of ‘natural justice’) needs to be entrenched in a society's codes in order to be effective. I have already noted that ideas about the proper content of retributive justice differ from society to society. Moreover, within any given society ideas about what is just change over time. Equal access to justice means not dealing with people in an arbitrary fashion but fairly, giving them a fair trial and dealing with them impartially and neutrally, without prejudice.

4.2 Social and political justice

A particularly important set of debates arises in relation to different notions of distributive justice. Do notions of distributive justice apply to the rights of individuals and the acts that they commit, or do they also apply to states of affairs, to the pattern of the results arising from those actions? In the former case, an outcome is just or unjust if it arises from just or unjust actions; whereas in the latter, the principles of justice apply to the pattern of outcomes. This latter notion is often described as social justice and is concerned with the fair distribution of goods and resources between and among the members of a society.

What is social justice?

A theory of social justice involves applying the principles of justice to the economic and social opportunities or outcomes in a given society.

This leads to the idea that social welfare should be provided (by the state in many countries) for those who need it, at a level defined differently in different places. Social justice is based on the concept that a state has responsibilities to its citizens, and can fund those responsibilities by levying taxation at a level acceptable to the members of that society, which again varies from country to country. ‘Fair distribution’ is, of course, inherently contestable.

Ideas of social justice aim to be in the interests of the community as a whole, and in the interests of social cohesion. This is also the basis of political justice –the notion that fixing the level of social justice and the rules of legal justice is something that does not happen ‘naturally’, but is established within a political order.

What is political justice?

A theory of political justice involves applying the principles of justice to the basic political institutions, the constitutional order, of society.

The state is responsible for the level of social justice and the rules of legal justices, usually based on the dominant political culture and identity. In many countries, establishing or reforming political justice involves healthy debate between conflicting views. This concept of social justice relates closely to what was said earlier about social and economic, and citizenship rights. As maintained by this view, equal citizenship involves social and economic rights so that everyone has the same access to justice. Critics of social justice argue that it often operates at the expense of individual rights, that in order for a particular pattern of outcomes to be achieved certain individual freedoms have to be curtailed.

5 Rights in the international arena

5.1 Rights, justice and international politics

What happens to notions of rights and justice when we move the discussion to the level of international politics?

In fact, three crucial things happen:

The meaning of rights takes its bearings from the rights discourse developed from the UN Declaration. We will investigate the effects of this, both on rights and on international politics.

We find that it is not always easy to establish who the right can be claimed against. In consequence, there can be a tension between the rights of individuals and the rights and authority of states.

The discussion of justice centres on the effectiveness of international organisations. The question becomes whether, and if so how, to strengthen the rights of NGOs, international institutions and international law to implement international justice.

A further dimension is added when we consider whether the development of the international human rights agenda now amounts to a form of globalisation. As Chris Brown notes:

[while] it was once the case that rights were almost always associated with domestic legal and political systems, in the last half century a complex network of international law and practice (the ‘international human rights regime’) has grown up around the idea that individuals possess rights simply by virtue of being human, of sharing in a common humanity.

(Brown, 2001, p. 599)

As you have seen, this is the core idea behind the concept of universal human rights.

In this section, we shall first look again at the international codifications of human rights and then discuss some of the problems associated with them.

5.2 Human rights in the international arena

The UN's 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights asserted that the ‘recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world’. It further affirmed that human rights should be protected by the rule of law, that they were ‘essential to promote the development of friendly relations between nations’, that these fundamental human rights include the equal rights between men and women, and that these rights represented ‘a common standard of achievement’. The Declaration also reminded member states of the UN that they had pledged themselves to promoting the observance of these rights.

The second half of the twentieth century saw an enormous growth of the rights discourse, whereby norms for universal domestic standards were elaborated. For instance, in 1966 the UN supplemented its 1948 Declaration with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Moreover, the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was signed in 1948, and further UN human rights treaties include the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination of 1965, and the International Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women of 1979. The UN's 1992 Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities also supplements its earlier Declaration; it amplifies the entitlements owing to members of minorities but does not contain prescriptions about the consequent duties of states.

Regional charters have also been made in Europe, Africa and America. The European Council set out the European Convention on Human Rights in 1950 under the headings of dignity, freedoms, equality, solidarity, citizens' rights and justice. The European Commission on Human Rights and the European Court of Human Rights provide the machinery to enforce these instruments. The European Union (EU) included an article asserting respect for human rights in the Treaty of Amsterdam, which came into force for member states in 1999, and the EU Charter on Fundamental Rights was proclaimed at the Nice Summit in 2000. The EU also includes human rights clauses in its agreements with other countries. The African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights was adopted by the Organization of African Unity in 1981 and has 51 state signatories. The American Convention on Human Rights was adopted by the Organization of American States in 1969 and has been ratified by 25 countries.

The extension of rights since the 1960s has also been made to many forms of ‘group’ rights, including women's rights, gay rights, the rights of the child, and post-colonial group claims. Furthermore, there has been an increased focus in the rights discourse on social, economic and cultural rights, as well as on civil, legal and political rights. Most recently, UN agencies have talked of ‘mainstreaming’ rights in development work, peace and security operations, humanitarian relief and social programmes.

The primary practical benefits claimed for the rights discourse include enfranchisement, the extension of rights to groups which were previously socially excluded, and the recognition of an entitlement to complain about inhuman treatment. According to rights advocates, other benefits include the acknowledgement that hitherto silenced groups and oppressed minorities also have a voice, and facilitating socially inclusive policies. For its proponents, while the rights discourse may make a community unstable by legitimating social conflict, it forces institutions to justify themselves. More broadly, advocates of universal human rights argue that the introduction of rights has led to the legalisation of a normative order, whose intentions are to advantage the disadvantaged and lead to a lessening of civil and international conflict. However, in this course we would like to draw attention to the fact that there are costs and problems associated with rights and the progressive legalisation of the international order as well as benefits.

5.3 Problems with international rights

The international human rights discourse claims that the value of its conception of rights lies in it being universal, empowering and human-centred. The idea of universality asserts the relevance of human rights to anyone, anywhere. Empowerment is the concept of human rights as a defence against inequality and the domination of the powerful over the weak. The human-centred feature of international rights seeks to provide a perspective on global questions, ‘putting the value of human dignity above the search for economic gain or the narrow interests of particular national governments’ (Chandler, 2002, p. 1).

We would like here to identify four specific sets of problems and a wider concern for this discourse:

The rights discourse is not universal but is deeply informed by a Western perspective (see Section 5.4)

Feminist critiques dispute the universalism of rights and argue that they have a masculine bias (see Section 5.5).

The question of who can claim what rights against whom is another area of difficulty (see Section 5.6).

The fourth problem is a specific instance of the third, relating to the way that individual rights may trump state sovereignty, and it challenges the human-centred feature of the international rights discourse (see Section 5.7).

As you will note, some of the criticisms that are developed below are objections to rights in principle; others are objections that rights are not realised, or are hard to realise, in practice.

5.4 The influence of the Western perspective

With regard to the first set of problems – that the rights discourse is not universal but is deeply informed by a Western perspective – it is striking that many actors and commentators on the international stage now frame their arguments and assertions in terms of the language of rights and justice. Yet we need to ask to what extent this language of rights and justice really underpins shared understandings and values. There is a strong case for saying that if there are shared understandings of rights and justice, they are a result of the power of the West by force or example, rather than common responses to similar sets of circumstances.

The cultural specificity of the current rights agenda cannot easily be overcome, because it derives directly from an Enlightenment and modern, rational, Western tradition and its accompanying context of emancipatory, progressive, liberationist politics. Rights in this sense cannot simply be applied to other places and times. This partially refers to the distinctively Eurocentric and liberal elements in the construction of ‘rights’ and ‘justice’. These elements include the particular liberal idea of tolerance and impartiality between different standpoints and between different normative evaluations in international relations, resulting in a healthy pluralism.

A further element concerns the characteristically abstract, universal, foundational and individualised notions of autonomy, equality and freedom found in the Western liberal tradition of rights and justice. A distinctively Western-inspired element informing the discourse is the ideal of social democratic egalitarianism. The critique of the Western currency for the dominant meaning of, and agenda for, rights and justice notes the specificity of the Western rights discourse. That discourse is linked not only to liberal principles but also coincides with a democratic political agenda, and the growth of a democratic culture of egalitarian citizenship.

Reading international rights through the lens of Western concepts can lead to distorting effects. For instance, some critics have argued that there is an unwarranted tendency in both Europe and North America to see human rights as problems for other countries but not for themselves, and to be complacent about poverty and institutionalised racism in Western countries. Critiques of rights notions in the West are often disregarded yet deserve to be taken seriously. The criticisms from some Muslim groups, for instance, of the objectification of women's bodies and the power of the pornography industry in the West, are well-placed.

Another example is that the conditions often tied to humanitarian aid for developing countries have the effect of politicising aid from Western governments and increasing their control, instead of simply universalising the right to aid. This analysis also extends to questioning the limits of the Western emancipatory agenda in the light of the power of market capitalist multinational corporations. This view believes that the Western rights agenda simply masks another form of hegemonic power, domination and subjection.

Critics of the Eurocentric and liberal nature of the dominant meaning of rights point to other definitions of rights and justice in non-Western countries and to non-Western conceptions of human rights. Such alternative definitions of rights draw upon religious or community identities rather than those of citizens within the territorial nation state. For instance, human rights in some Muslim societies contain the idea of separate and equal spheres for men and women rather than universal egalitarian rights. Traditionalist conceptions of human rights exist in China and different African societies, and in cultural values informing the caste system in India. ‘Asian values’ is a prominent alternative form of human rights conception which is less individualistic than the Western-derived notion, and places greater value on religion, family and elders.

Since the end of the Cold War divisions between the West and the Soviet bloc, the human rights discourse and agenda have become even stronger guides to policy making. The dominant human rights discourse can appear universal since the decline of Cold War barriers to international regulation. The move to a world dominated by a single superpower has given the illusion that a particular definition of human rights as a policy instrument is universal. Nonetheless, a strong case can be made that the meaning of international human rights should be derived from theoretical analysis and debate and not, by default, from geo-political shifts in international relations alignments.

Problems with the universalisation of a Western rights agenda are closely linked to problems with the idea of international rights as empowering. The assumption that the human rights culture will empower those who have been marginalised or excluded from the political process can be questioned. To illustrate, consider the UK Department for International Development (DFID) view that the ‘human rights approach to development means empowering people to take their own decisions, rather than being the passive objects of choices made on their behalf' (2000, p. 7). In practice, instead of granting new rights, it is sometimes the case that good intentions are not fulfilled. Chandler notes that the ‘rights of advocacy claimed by international bodies provide little accountability for those they claim to act on behalf of, while potentially undermining existing rights of democracy and self-government’ (Chandler, 2002, pp. 14–15). There is evidence that the human rights framework can have the effect of empowering international institutions rather than those they claim to represent.

There is also a strong argument that the meaning of international human rights is not widely shared but has been driven by particular contingent crisis situations. Debate has tended to centre on specific ad hoc cases and not on the broader consequences of the prioritisation of a human rights agenda.

Debate has also focused narrowly on how to make institutions effective in implementing their new role, rather than on the broader implications of the shift they are bringing about in international organisations and policy making. Likewise, there has been very little discussion of the theoretical basis of the central justification for this understanding of human rights. As Chandler observes, for ‘many commentators, the human rights framework appears to be justified as a fait accompli because governments and international institutions have already accepted it’ (Chandler, 2002, p. 12). The international human rights culture is so well established that it has deterred the kind of sustained theoretical debate that developed in previous centuries over rights which were understood within a nation state context.

5.5 Feminist critiques of international rights

The second source of criticisms that we would like to explore comes from feminist critiques. Some feminists argue that the universal notion of rights makes invisible the special problems faced by women as a group, and that, thereby, specific articles of the various human rights declarations and conventions reinforce traditional gender roles in the family and the workplace. This criticism comes in at least two forms.

The first is that rights for women (as for other disadvantaged groups) may be particularly difficult to enforce against the claims of the powerful and the dominant. An example is the poor pay and conditions, and isolation faced by women ‘home-workers’ in developing countries. Catharine MacKinnon (1993) documents forms of gendered ill-treatment and harm to women, including sexual and reproductive abuses, rape as a weapon of warfare, forced motherhood in Ireland, domestic violence against women as part of the honour code in Brazil and Italy, and suttee in India. Such human rights abuses are not prevented by universalistic human rights conventions. Further examples concern the sexualization of women's and children's bodies in international prostitution. Examples include the market for sex workers for tourists in the Philippines or Barbados, sex workers to service American bases, and the influx into Western Europe of prostitutes from Eastern Europe by mafia gangs.

The second form of this feminist criticism is more far-reaching, arguing that making effective a given right, say, the right to employment, may have different implications for men and women. In a context of pre-given unequal distribution of domestic and reproductive labour, equal employment rights for men and women may involve a transformation in childcare arrangements, for example. Without such a transformation, equal rights may perpetuate inequalities. The rights regime needs to recognise the impact of rights in structuring and maintaining inequalities.

5.6 Against whom are rights claims made?

The third set of problems relates to whom the rights claims are made against, and what kinds of claims can be made. In the case of individual human rights, a rights claim is usually addressed to or claimed against the legal order of the state. However, it is often one of the problems at the international level that either the state claimed against does not recognise the claim, or that the body claimed against is not a state (that is, a political entity that is in some sense morally accountable) but, say, a corporation. An example is the fight of Nigerians against the Shell oil company. The international sphere of politics in its own right is made up not just of states but also of other powerful organisations and institutions, including regional political and economic organisations such as the EU and North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and transnational economic organisations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. Non-state actors also include multinational corporations, paramilitary forces and radical religious groups. It is often difficult to bring non-state actors who are responsible for human rights violations to account.

Another group of actors on the world stage is international NGOs such as Amnesty International, and aid-giving and development charities such as Oxfam. The diversity of international actors makes the picture of the international sphere more complex. International NGOs are playing a greater and greater role in international politics. For instance, at the 1993 UN World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna, over 500 NGOs were represented, almost equalling the number of state representatives, and at the 1995 UN World Conference on Women's Rights in Beijing, most of the 35 000 participants were from NGOs. Some commentators see these developments as demonstrating the increasing influence of ordinary people, generating a ‘people's politics’ which is campaigning to hold governments to account. Yet at the same time international NGOs are largely unregulated and unaccountable to a wider public.

Due to the fact that the link between rights claims and responsibility is more opaque at the international level than at the national level, human rights are more difficult to claim than might be envisaged from a simple focus on the individual and the state. The language of rights is often not effective in promoting egalitarian remedies for ill-treated and discriminated groups, and can raise expectations among the disadvantaged that it cannot meet. It comes as a shock to hear that, 50 years after the UN Declaration, it has been estimated that there are 27 million slaves in the world. Slavery is defined as the complete control of a person through violence or the threat of violence in order to exploit them economically. Slavery has changed its face since its traditional forms and now predominantly involves, for instance, the sale of 14-year-old girls into brothels in Thailand, and the sale of girls from Mali to work for families in Paris. The tripling of the world's population since 1945 and the prices of slaves being at an all-time low help to account for the current high number of slaves. Slavery is just one category of human rights violation that carries on and even increases, despite ‘rights’ talk.

The UK DFID document, Realising Human Rights for Poor People (2000), accepts that there is a ‘large gap between the aspirations contained in the principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the experiences of people living in poverty’. The report notes that there are ‘problems with relying solely upon legal measures for the protection of human rights’, since ‘poor people are rarely able to use formal legal systems to pursue their claims’ (DFID, 2000, p. 16). For example, the on-going murder of street children in cities across Latin America leads to the question of whether the interests of those street children are best advanced through international action based on human rights.

Another aspect of this issue concerns which rights states say they can and cannot respond to. There is a question about whether legal, civil and political rights, economic and social rights, and group rights are all compatible with each other. Commentators sometimes refer to the history of the development of the rights culture over the second half of the twentieth century in terms of: ‘first generation rights’, which focused on individual broadly political rights; ‘second generation rights’, which targeted individual economic, social and cultural rights; and ‘third generation rights’, which were concerned with group rights. Indeed, Brown raises the question of whether second and third generation ‘rights’ are ‘rights at all?’ (Brown, 2001, p. 601), although it is clear from Table 1 that even the original UN Declaration went far beyond ‘first generation’ rights. Nevertheless, social and economic rights might be impossible to meet for a cash-strapped state. Furthermore, governments have been known to argue that the development of social and economic rights through the promotion of economic growth must take priority over and preclude the possibility of the early granting of political rights.

5.7 Relating individual rights to state sovereignty

The fourth set of problems is really a specific example of the third set and relates to the ways in which individual rights relate to state sovereignty. The Millennium Conference of the UN in 2000 endorsed the need for people-centred changes to the institution and renounced its previous ‘state-centred’ structure. The human-centred logic of rights regards human rights as a value which places legitimate constraints upon the politics of national self-interest and interstate competition. Chandler notes that at the 1993 ‘UN World Conference on Human Rights’ in Vienna, ‘the UN Charter was widely construed to mean that human rights should take precedence over sovereignty’. Moreover, he argues that, ‘by the end of the 1990s, with UN protectorates established in Kosovo and East Timor and the indictment of former Yugoslav president Slobodan Milosevic for war crimes, international relations were no longer seen to be dominated by the need for inter-state consensus’ (Chandler, 2002, p. 8).

Do human rights provide a universal principle on which to justify intervention that ‘trumps’ state sovereignty? There is no current consensus about what constitutes sound arguments to justify forms of legitimate intervention. Besides, the line between humanitarian and military intervention can be a very blurred one. The current human-centred approach to rights can also lead to unwanted consequences. Understanding human rights conflicts on the model of victim and abuser can lead to a moralised discourse where the underlying grounds of the conflict are neglected, the victim is regarded as incapable of remedy without international assistance, and the abuser is considered as incapable of adopting right over wrong.

There is some proof that this model, applied to the Rwandan genocide for instance, has neglected the wider political and social framework in which mass killing took place. There is also evidence that in media coverage of Bosnia and Rwanda, ‘public understanding of these conflicts has been distorted by advocacy journalists calling for military intervention against demonised human rights abusers’. Analysis of the Kosovo crisis also suggests that ‘human rights intervention can easily become a dehumanising project of bombing and sanctions in the cause of great power interests’ (Chandler, 2002, p. 15).

5.8 Review of criticisms of international rights

Activity 1

Review the four criticisms of rights at the international level discussed in the previous sections.

Identify which of these criticisms are objections in principle to the discourse of universal human rights and which are objections in practice.

Identify which of these criticisms relate particularly to implementing rights internationally and which might apply to rights more generally.

Discussion

There is in fact sometimes no clear dividing line between principle and practice; that is, the line between the two criticisms is often blurred. Nevertheless, objections in principle might include the argument that universal rights are Western in origin and therefore cannot be universal. However, the related criticism that Western countries criticise others' human rights records and not their own is not an objection to rights in principle, just to the uses of rights discourse by Western states. Similarly, the criticism of DFID is about the non-fulfilment of rights in practice not principle.

Similar distinctions can be made about the feminist critiques. The objection that women's rights are particularly hard to enforce is one of practice – a product of patriarchy. The argument that specifying universal rights obscures the different problems that women face is more of a principled objection to universal rights claims. The objection that rights at the international level create the problem of against whom rights should be claimed is a principled objection, although it leads to the practical problem that rights are not in fact realised for many people.

Criticisms that pertain particularly to the international level are the Western origin of rights, and the problem of against whom rights claims should be made. Feminist criticisms could apply to rights viewed entirely in the domestic sphere.

These criticisms sharpen the idea that there is a gap between principle and practice. The human-centred approach refers to the view that moral and ethical considerations should be central, rather than policies being mediated either by profit or by the grand ideological designs of left-wing and right-wing politics. Nonetheless, the disjunction between the pure, principled character of rights and the real world of conflicting interests, compromise and power politics throws this feature into question. In part, this is due to the problem that abstract human rights (as propounded in the UN definition) are only or ‘merely’ rhetorical unless they are backed up by the capacity to implement and operationalise them, and unless they are recognised by the country in which one lives. Rights may belong only to ‘discourse’ and not be ‘real’. In support of this view, some critics maintain that the evidence shows that rights have not, in practice, impinged much upon states' national interests or the interests of international financial and trade organisations, let alone on national and international violence and intervention.

6 International justice – communitarian and cosmopolitan perspectives

6.1 Introduction

The international level can be viewed as an arena of politics in its own right and not just as a context for states and other actors. If we think of the international world in this way, how should relations between states, and other actors on the international stage, be constructed? To what extent should those relations be regulated? We can ask whether relations between states, and states' policy making, should be dictated by allegedly universally shared human rights principles, or by other objectives such as national political or economic interest, regional interest, international peace or serving alliances with other like-minded states. A related consideration is whether relations between states should be driven by moral principles such as rights and justice, or by other legitimate interests?

A distinction can be made between two different ways of understanding the role of states in international society: first, as ‘local agents of the common good’ in an order of (increasingly universally) shared notions of human rights; and second, as the embodiments and protectors of different cultures or civilisations in an inherently plural modus vivendi. The question is of more than academic interest, since how we think about the international sphere affects how real world actors operate in it. The debate between the communitarian position and the cosmopolitan position has developed as the primary way of structuring this issue and we will consider it further now. The communitarian/cosmopolitan debate takes a theoretical and normative approach to the role of rights and justice in different conceptions of the international realm.

This section will outline and compare the communitarian and cosmopolitan positions, and then introduce the understanding of rights found in each case, leading onto a discussion of two contrasting forms of international justice and intervention in the light of the two perspectives. While there are differences between advocates of communitarianism and among proponents of cosmopolitanism, the two viewpoints can be characterised as broad umbrella positions championing a particularist and state-centric perspective, and a universalist and global perspective respectively.

Section 6.2 will discuss theoretical and normative issues, while Section 6.3, Section 6.4 and Section 6.5 will consider how the two positions inform highly charged political debates on international distributive and retributive justice and the question of intervention. It should be clear that, in line with the critical view of rights adopted in this chapter, we think the communitarian case is the stronger one. However, we hope this sympathy will not lead us to be unjust to the cosmopolitan viewpoint.

6.2 Some general features of communitarianism and cosmopolitanism

There are two very different and sharply contrasting views about how the international arena can be theorised, should be organised and can be described. One side sees the international sphere as made up of a plurality of interacting cultures with incommensurable values, while the other side deploys general concepts of rights and applies these to humanity as a whole. These two constructions rest upon very different views of what human beings are, and how they do and should interact together.

Communitarians understand human beings firstly in terms of their cultural identity, while according to cosmopolitans reason should be, though perhaps is not always, the governing principle of human interaction. The cosmopolitan belief in the emancipatory power of the human capacity for reasoning derives from the idea that reasoning is a shared capacity capable of providing the basis for moral principles which aim to deliver humankind from the mire of ignorance and superstition. Cultural identity and the human capacity for reasoning are strongly divergent principles on which to base the construction of international politics.

For communitarianism, the international arena is dominated by states but this does not discount the role played by other, subordinate actors to help coordinate interstate activity. International NGOs, international regulatory organisations like the World Bank and IMF, the UN as a forum for states, and global civil society campaigns such as the campaign to end apartheid in South Africa or anti-globalisation protests can all play a role, provided that states are still regarded as central. However, public debate on the role and basis of legitimacy and accountability of organisations such as the IMF, World Bank, World Trade Organization (WTO), and International Labour Organization (ILO) remains to be conducted.

As stated by cosmopolitans, the international arena is a public sphere and potentially an arena of governance in its own right. Some cosmopolitans look forward to a global order with a stronger set of institutions above states. Areas identified as requiring faster reform include the composition of the UN Security Council and the power of veto by its permanent members, and the restrictions on international intervention arising from the UN Charter and from state sovereignty. The form of accountability that supranational institutions would have, how that accountability would be delivered, and to whom, remain in question.

Communitarians distrust claims made for proposals of cosmopolitan democracy, advanced for instance by David Held (1995), on the grounds that it can be questioned whether the proposed frameworks to extend democracy at the international level will bring about the empowerment of the ‘global citizen’. There are fears that the mechanisms of regulation envisaged by cosmopolitans, based on ideas such as international civil society, cosmopolitan governance and cosmopolitan citizenship, do not involve sufficient means of political accountability, and instead provide more opportunities for freedom of action by leading world powers.

Communitarians argue that rights and justice are culturally specific and cannot be applied across borders. They consider that what we have in the world, and what should be valued in a positive sense, are different, plural, political communities with divergent and incompatible interests. They hold that the diversity and heterogeneity among a plurality of communities and their values is as important to sustain as is a diversity of species among animals and plants. Communitarians contend that while moral principles should have a place in the conduct of interstate relations, there are no overarching principles sufficiently widely endorsed to form the basis for a strong legal authority that would limit the claims of the sovereign state. The UN and other international organisations are valid if they help to co-ordinate communication and action within the complex society of states, but such organisations should not seek to supplant the sovereign state as the highest law-making body for its domestic population. The key principles to uphold are those of the self-determination of peoples, and the legitimate rights of a state to manage its own affairs and to defend itself from interference. States should respect one another's independence.

Communitarians claim that the separate communities (most often nation states) remain the basic building blocks of international relations, and that reasonable states have political institutions, governments, electoral systems, the rule of law, and constitutions, all of which should together be the focus of political activity for citizens. Although some issues, such as global environmental problems and morally-motivated aid to developing peoples need to be regulated globally, this is best achieved through interstate coordination. We should value an international society of sovereign states whose interaction is based on the principle of non-interference.

As maintained by the communitarian position, human rights cannot be defined universally because they only have meaning in terms of the social fabric of the particular societies and cultures that proclaim them. ‘Human rights’, it is argued, mean something different in Somalia from what they mean in the context of, say, Japan. ‘Human rights’ is a term that only has meaning when anchored in particular political allegiances and an explicit historical development. Communitarians hold that rights are grounded in specific cultural understandings and have no universal fundamental basis, and that they should instead be recognised as radically socially constructed. They question the usefulness of universal definitions of rights and justice, arguing that such definitions are so abstract that it is difficult to apply them and to match them to any specific situation. They are so universal that they do not take account of different social and cultural contexts and histories. These definitions also narrow the range of acceptable action. As Brown notes, the ‘very idea of human rights implies limits to the range of variation in domestic regimes that is acceptable internationally’ (Brown, 2001, p. 610).

The communitarian critique of the international human rights culture extolled by cosmopolitans also argues that, in this reading, rights are so fixed that they do not allow any challenge. In order to be useful in the real world of politics, definitions of rights and justice, like other political concepts, need to be interpreted. The concept of rights is clear but thin, and too far removed from real life. What we need, according to communitarians, is different, thick interpretations of the concept, that is, diverse conceptions. Yet as soon as we start talking about different conceptions of rights and justice, we begin to realise how complex and contested those conceptions are. Do they then lose their universality? The price of having conceptions that fit real situations is that there are no agreed fixed meanings to refer to in order to referee disputes. There is no neutral language with which to discuss international human rights, and all perspectives carry an ideological charge. There is no objective ‘God's-eye’ view from which to arbitrate.

Moreover, some communitarians also believe that ‘rights’ talk individualises and fragments social bonds. It is necessary, in contrast, to think about values for society as a whole. In addition, the communitarian perspective might argue that ‘relationality’ (the idea that our relations with others are as important to our well-being and individual identity as our sense of individual freedom and rights) is profoundly important to us. A standpoint which does not recognise that our needs are usually interdependent with those of others, and so does not take relationality into account, can lead to damaging consequences for all concerned.

The communitarian position is strengthened by the argument that many human rights conflict with each other, for instance, potentially between a mother and her unborn child. Its appeal is also fortified by pointing out that because the meaning of rights is contextual, many interpretations will conflict, and there is no obvious principle to appeal to for resolving disputes of interpretation. This view holds that the answer to the dilemma lies in the need to compromise absolutely-held political positions and convictions. Compromise and consensus can only be achieved politically, on a case-by-case basis. This quandary occurs at the international level as well as at the domestic level, and can only be settled by a process of negotiation between the particular set of actors involved, not by reference to some overarching ‘global institution’ or principle.

Activity 2

Rather than seeking a single set of human rights upheld by all states, communitarians argue that we should value a diversity of ‘reasonable’ ways of living together and, therefore, different conceptions of the political good in international society. What, if any, are the limits to what is ‘reasonable’? On what grounds should we accord respect to other cultures?

Discussion

This one is difficult. You might find it helpful to work through the following argument of David Beetham.

[I]t is difficult to see why we should accord equal respect to other cultures except on the basis of the equal human dignity that is due to the individuals who are members of those cultures. And if we accord them equal dignity, is it not as those capable of self-determination and as having a legitimate claim to an equal voice in their own collective affairs? To be sure, we have long since progressed from the simplistic Enlightenment assumption that equality denoted sameness. Indeed, the capacity for self-determination is precisely a capacity to be different, both individually and collectively, and a claim to have these differences respected by others. But that capacity also sets limits to the cultural practices that can be endorsed by the principle of equal respect … Without a strong principle of equal respect for persons, there can be no reason except power considerations why we should not treat cultural difference as a basis for exclusion, discrimination or subordination; with it, we are bound to take a critical attitude to those cultural practices that infringe it, and not merely because we find them different and alien from our own.

(Beetham, 1999, p. 15)

Table 2 summarises the difference between the communitarian and cosmopolitan perspectives.

| Communitarianism | Cosmopolitanism | |

|---|---|---|

| Principle of human interaction | Cultural identity | Reason |

| Basis of interaction | Plurality of intersecting cultures with incommensurable values | Single humanity with everyone having equal moral worth because all human beings share capacity for reason |

| View of international system | System dominated by sovereign nation states that co-operate and conflict with one another | Suprastate public sphere and an arena of governance in its own right |

| Preferred form of international authority | Sovereign state and interstate institutions, no strong legal and political authority above the state | Community of states upholding universal human rights and international law |

| Basis for addressing common problems | Common problems are best addressed through co-ordination between states | Common problems governed by principle of universal rights and the related principle of universal international justice |