Managing Complexity: A Systems Approach

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 16 April 2024, 5:00 PM

Managing Complexity: A Systems Approach

Introduction

When you meet with a situation you experience as complex you need to think about yourself in relation to the process of formulating a system of interest. Only with this awareness, can you increase your range of purposeful actions in the situation which are ethically defensible. To do so is the hallmark of systemic thinking and practice compared to systematic thinking and practice. The metaphor of the systems practitioner as a juggler of four balls is introduced as a device to explore skill development for effective systems practice – the balls are ‘being’, ‘engaging’, ‘contextualising’ and ‘managing’.

To start, you will be invited to think carefully about yourself in relation to the unit itself – as an introduction to thinking about yourself in relation to any system you devise. This unit introduces the metaphor of the systems practitioner as a juggler of four balls: ‘being’, ‘engaging’, ‘contextualising’ and ‘managing’. This provides a device to explore skill development for effective systems practice.

This OpenLearn course provides a sample of level 3 study in Computing & IT

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

reflect on personal purposes and expectations of doing this course

record personal initial and developing understandings of what the course is about

keep an on-going record of these developing understandings, expectations and experiences

use a Learning Journal to record any reflections

take responsibility for these reflections.

1 Managing complex systems

1.1 Thinking about expectations

Anticipations and preconceptions are an important determinant of how people learn, so before you read on, I would like you to record some of what you are experiencing now as you begin the unit.

It's important to get these impressions noted down now, because new ideas and new impressions will quickly overlay the experience. What you are experiencing now will be re-interpreted as new understandings emerge. You are also likely to form some judgements about your expectations. So before any of that can happen, make some notes on your responses to the questions in the activity below. I suggest you make your notes in a form that allows them to be incorporated, either directly or indirectly. You will need to keep referring back to them as the unit progresses. It will also be helpful later if, as you make notes, you date them and leave space for later thoughts and jottings. Your notes should capture as many elements of your responses as possible.

The notes that you make for this, and some of the other activities, will be important later. You should do them as conscientiously as possible. Their role in developing your skills will become more evident as you continue your studies in the area. Your notes should capture as many elements of your responses as possible.

I anticipate you might spend around 90 minutes on this activity. It may take longer. This may seem like an enormous amount of time, but thinking about the issues carefully is likely to take that long.

Activity 1

What is your purpose in doing this unit?

What do you hope to get from the unit? I imagine you might have some expectation that you will enjoy, or benefit from, doing the unit. What benefits do you expect? What was it in what you heard about the unit that suggested you might benefit from it? What was it about the unit or its descriptions that appealed to you? What is it about you that the unit appealed to? Not everyone chooses to take this unit so there must have been something about you that connected with what you heard, or read, about the unit. Make a note of any specific items that appeal to you. Make a note too of any items that worry or concern you.

What is your emotional state as you approach the unit?

Are you excited, bored, eager, puzzled, expectant, tired? What is your present body posture? Does it tell you anything about how you feel? Is it right? Can you improve your physical comfort?

Are you comfortable with your workspace? Are there things you can do to improve it?

What sort of skills and capacities do you think you might need for the unit? How many of these do you have already? What skills will you need to pick up? What will you need to look for in the unit to acquire these skills and capacities?

How does your answer compare with your notes on what you hope to get from the course? Are they congruent or does the answer to this question throw new light on what you hope to get from the course?

When you make a judgement about how you rate your capacities, what are you basing it on? Are you taking account of external factors such as the time you have or the circumstances in which you study? Are you basing your judgement on your own evaluation of your intellectual capacities? Do energy, enthusiasm and commitment come into the evaluation?

The activity you have just engaged in is the first of several such activities. It is an example of a pattern of activities that constitute reflective practice or reflective learning. This style of learning is based on the notion that the understandings most useful to us, and that most readily become part of us, are learnt by experience. The activities are designed to enable you to discover your own learning by experience.

There will be a lot about reflective practice in this unit but for now I want to introduce you to some basic ideas about it.

1.1.1 Learning by experience

It's a familiar idea but it implies two activities: learning and experiencing. Both activities need to happen if I am to say that learning from experience has happened. Experiencing seems to have two components. The first is the quality of attention that allows me to notice the experience and its components. The second is memory. Calling experience to mind allows me to examine the experience and to think about it in ways that were not possible at the time. Learning is what I take away from that process that influences my behaviour or thinking in the future.

But huge amounts of experience escape without being consciously experienced; I am insufficiently aware at the time to notice what's going on. Later I am too busy to recall the experience and so little conscious learning takes place. Of course, it's useful to carry out familiar activities ‘on auto pilot’ – without conscious attention. It's easy to miss out on important learning from unfamiliar activities too. I may become wrapped up in the activity itself or simply not notice the range and quality of the experience. Either way, a conscious attempt to recall the experience and to think about it, gives the opportunity to learn from the experience.

So, what was my purpose in asking you to do the activity above? I wanted you to experience the starting of this unit as richly as possible. I was asking questions that I hoped would prompt you into awareness of what you were experiencing. It may be you discovered something new about yourself; your expectations of the unit; what you hope to gain from studying it; or about your capacity to succeed in it as a result. If not, don't worry. The point of the activity was raising awareness rather than discovery; and recording material that will be useful in future learning and reflection.

Spend a total of about 15 minutes on the next two activities.

Activity 2

What do you understand the course title from which this unit is taken to mean?

The title of this course is Managing complexity: a systems approach. Before you go any further, make notes about what you understand by the term ‘managing complexity’.

What do you understand by a systems approach? Don't worry if you feel you only have vague ideas at this stage; record all your ideas as fully as you can by listing all the things you think it might mean. You may also wish to distinguish ideas you feel confident about from those you are not sure of.

Activity 3

Add any further thoughts about your expectations.

You may feel some of the expectations you had have already been changed. Add any postscripts about this to the notes you made earlier. Make it clear in your notes these are postscripts and what has happened to change your views.

This unit is taken from a level 3 Systems course. This carries certain implications about its level and its likely content. You are likely to have drawn some conclusions about what these implications are. Recognizing explicitly the presuppositions and assumptions you carry into a situation allows you to examine them. Presuppositions can get in the way of understandings. For example, if I assume a book is just about koalas, and don't notice it's about koalas in their eucalyptus habitats, I am quite likely to experience the text about eucalyptus forests as a distraction. This might lead me to misunderstand what the text is saying about eucalyptus habitats and, almost certainly, I would misunderstand its importance to the koalas. At the very least this will make me an inefficient reader and may make me an inefficient learner.

The next activity will help you to think through your expectations, assumptions and presuppositions about this course.

Allow yourself about 30 minutes to do Activity 4, making notes as before.

Activity 4

What activities do you expect to undertake in studying a level 3 course?

You may already have some experience of Open University courses. You may have other experiences of studying. What sort of activities do you expect to engage in when you study a course? What sorts of activities have in the past been most effective in enabling you to learn? These questions are easier to answer if you think back to a specific course or other learning experience. What did you actually do? What were the components of that course? What was their relationship to each other? If you have studied only level 2 courses before, what differences do you expect in a level 3 course? If you have studied at level 3 before, can you identify any differences between those courses and other, lower level courses?

Which components of your previous learning experience have you enjoyed most? Why?

Some people enjoy the initial meeting with new material most. Others enjoy testing their newly acquired understandings in exercises. Still others enjoy their new perspectives on things quite external to the course that their new understandings give them. Do any of these match your previous experience? If not, what was it for you? You may also like to explore the question of what you didn't like. Have you changed in ways that might make your experience of this course different?

What were you, as the student, expected to do as you worked through previous courses?

Many courses follow a fairly steady pattern of a bit of theory, followed by an example of what the theory means in practice, followed by an exercise where the learner applies what they have just learned to another situation. Do you recognize this pattern? Have you experienced it? Have you experienced variations on this theme? What were they? Have you experienced alternative approaches? How successful have these patterns been for you? Success, in this sense, might mean examination success or it might be a success criterion you have set yourself, or one you want to apply now. It may parallel the criteria for success you identified for this course.

2 Preparing to tackle this unit

2.1 The nature of systems thinking and systems practice

There are no simple definitions for either systems thinking or systems practice. It's difficult to find definitions that capture all the perspectives that the ideas carry for people who think of themselves as systems thinkers and systems practitioners. Most systems practitioners seem to experience the same kind of difficulty in explaining what they do or what it means to be systemic in their thinking. Through experience I've developed some criteria by which I characterize systems thinking, but they seem to be quite loose in the sense that those characteristics are not always observable in what I recognize as systems thinking. In any case, they seem to be my list of characteristics, similar to, but not the same as, other people's lists. This issue will be developed but, for the moment, I would like you to hold the idea that systems thinking and systems practice arise from particular ways of seeing the world.

My hope is, through interacting with the unit and asking yourself questions about your experiences, you will discover at least some of these characteristic ways of seeing the world. If you have previously studied Systems courses, you will already have experienced forms of systems thinking and perhaps ‘caught’ it in some way. You may even have developed your own understanding of systems thinking and what it means. If you have not experienced a Systems course before, you need to be aware that this unit cannot make you into a systems thinker or a systems practitioner. It can only provide you with a framework through which you can develop your own characteristic ways of being a systems thinker and a systems practitioner. You will already have encountered, in previous Systems courses or through your preparatory reading, some of the central ideas of systems thinking.

Gather up your ideas of what these central ideas are by spending around 15 minutes on the following activity.

Activity 5

Make notes on what you think are the main features of systems thinking.

This is not a test question. There are no right or wrong answers. I am simply inviting you to explore what you already understand about systems thinking. Try to make your answer as comprehensive as you can. You could use diagrams if they're a more convenient way for you to represent your ideas.

If you have already studied Systems, you may find this task quite demanding because you will have to abstract these general ideas from what may be quite detailed understandings. Don't be afraid to spend slightly longer on this if you need to.

Try to ensure that, in doing this activity, you are building your understanding and not just abstracting a list from someone else's ideas.

As before, date your notes and leave room for later additions.

Your notes from this activity will form a powerful basis from which to build your understanding of, and capacity for, systems thinking. You will develop your own ways of working with the notes you take as you work through the course. My own way is to add new material in a different coloured ink, indicating the date of the new colour. I've also sometimes photocopied the notes and added new notes to the photocopy, which I photocopy again for yet more amendments and crossings out, dating each one as I go. This saves completely re-writing and I only need to rewrite when I have a different appreciation of something, or when it has developed so far the old version is no longer helpful as a foundation. Other people use computer files in a similar way. I prefer not to throw away any old version, even if it gets superseded. It provides me with a record of my developing understanding, especially if I note down what I now understand and why I now think the old understanding is unhelpful. Even notes I think are redundant can prove to be the anchors for new insights.

You don't have to do it my way but I would urge you to find a way that suits you. You will need to be able to record your own learning: perhaps even more importantly, you will find these notes invaluable as you take responsibility for your own learning.

My own answer to Activity 5 follows

You should not treat this as the right answer. You should certainly not make judgements about your own performance in the light of my response. My notes arise from my experiences, yours arise from your own. I would like to think you and I were both engaged in an activity that gives rise to new experiences and thus builds our own understandings from our own experiences. So I would much rather you treated the following as if we were in a conversation and use my ideas to develop your own.

The important features of systems thinking, as I see them, are these.

-

Systems thinking respects complexity, it doesn't pretend it's not there. This means, among other things, I accept that sometimes my understanding is incomplete. It means when I experience a situation or an issue as complex, I don't always know what's included in the issue and what's not. It means I have to accept my view is partial and provisional and other people will have a different view. It means I resist the temptation to try and simplify the issue by breaking it down. It also means I have to accept there is more than one way of understanding the complexity.

Complexity can be quite scary. But it need not be: complexity becomes frightening when I assume I ought to be able to ‘solve’ it. Systems thinking allows me to let go of this notion and allows me to use a multiplicity of interpretations and models to form views and ideas about the complexity, how to comprehend it, and how to act purposefully within it.

-

Systems thinking attends to the connections between things, events and ideas. It gives them equal status with the things, events and ideas themselves. So, systems thinking is fundamentally about relationship and process. It is often the relationships between things, events and ideas that give them their meaning. Patterns become important. The nature of the relationships between a given set of elements may be manifold. They may be causal (A causes, leads to, or contributes to, B); influential (X influences Y and Z); temporal (P follows Q); or relate to embeddedness (M is part of N). These relationships spring to mind immediately but there are many others, of course.

This attention to relationships between things, events and ideas means I can observe patterns of connection that give rise to larger wholes. This gives rise to emergence. Thinking systemically about these connections includes being open to recognizing that the patterns of connection are more often web-like than linear chains of connection.

-

Systems thinking makes complexity manageable by taking a broader perspective. When I was studying engineering as an undergraduate, we were taught to break down problems into their component parts. This approach is so deeply entrenched in western culture it seems natural and obvious to anyone brought up or educated in this culture that this is the way to tackle complex problems.

While this approach is powerful for some problems, it's hopeless for others. For example, it now seems clear that climate change induced by human activity is likely to have major impacts on the planet, its environments, and its living organisms, including people. But all of these effects are so interdependent it is impossible to discover what the effects are likely to be by breaking the problem down.

Systems thinking characteristically moves one's focus in the opposite direction, working towards understanding the big picture – the context – as a way of making complexity understandable. Most people recognize they have been in situations where they ‘can't see the wood for the trees’. Systems thinking is precisely about changing the focus of attention to the wood, so that you can see the trees in their context.

Understanding the woodland gives new and powerful insights about the trees. Such insights are completely inaccessible if one concentrates on the individual trees. Figure 1 illustrates this sort of shift of attention vividly.

Systems thinking seems to come more naturally to some people than to others. Others have to learn to think systemically. People trying systems thinking for the first time find it quite tricky in the early stages. The temptation to break down the situation of interest into smaller bits is strong. The systems approaches you will encounter take account of this and are designed to enable you to capture the complexity before you move on to exploring it.

During the 1980s and 1990s, there were significant advances in Systems theory. There were two main drivers for this. One was the tremendous advance in computing capability. This allowed the behaviour of fluid, chemical, biological, and other phenomena to be modelled through time. This generated wonderful new insights into what came to be identified as chaotic phenomena. The second was the renewed synergy between biology and Systems. Both these stories are exciting, and there are a number of well-written books for the general reader that describe some of this work (see the box below).

Would-be Worlds (Casti, 1997, John Wiley & Sons Inc., New York) arose out of the computer exploration of systems behaviour. James Gleick's classic Chaos (1987, Penguin, London) is also in this tradition. Fritjof Capra's The Web of Life (1996, Harper Collins, London) explores some of the developments in biology that arise from a systems perspective.

Regarding the second driver, the synergy first emerged in the early 20th century among biologists concerned with the properties of whole organisms. This led to an exciting phase of synthesis of ideas from many disciplines that gave rise to General Systems Theory. Since that time, biologists who look at living systems as a whole have turned to systems theory for new insights and, in response to their findings, systems theorists drew new insights from biology.

For me, the practicality of Systems is even more exciting than these developments. This course is as much about systems practice as it is about systems thinking. There is an exciting synergy between systems theory and attempts to find better ways of engaging with problems and opportunities.

This is what the course is about. It is an invitation to engage with systems thinking in such a way that you are better able to address the problems, complexities and opportunities that you encounter as you engage with the nitty gritty of whatever you do. Systems thinking provides me with tools-for-thought and the opportunity for a powerful way of looking at the world, whatever the context. The contexts stretch all the way from international issues such as global warming to the day-to-day problems that arise in work, in domestic life and in the local community.

Systems practice in the context of this course refers to the practice of Systems within whatever profession or calling you follow. You can be a systemic medical practitioner, a systemic wood turner, a systemic technician or a systemic manager by applying systems thinking, insights and approaches to the complexity that you encounter in any of these or other domains.

2.2 Taking responsibility for your own learning

Not much of this unit conforms to the traditional pattern I mentioned earlier – the theory-example-exercise pattern. In particular, you will find you are expected to discover much of it for yourself. Why is this? This is a legitimate question and deserves a full answer. One year, a student at a residential summer school complained I had not taught him properly. I was, he told me, an expert and so why did I not demonstrate how to tackle the problem he was working on and pass my expertise on to him. He felt the tutorial was ‘a wasted opportunity’. I could understand why he felt aggrieved. But I think he had missed an important feature of learning a skill such as systems thinking.

More and more, I've come to realize that whatever expertise I may have in systems thinking and practice, it is my expertise and it only works for me. In this I find myself in agreement with C. W. Churchman ‛Churchman, C.W. (1971) The Design of Inquiring Systems, Basic Books, New York”, who was one of the first people to write about what systems thinking might mean in practice, when he said ‘there are no experts in a systems approach’. When I look at the people whom I believe to be experts in this area, I realize there are many ways of being good at systems thinking and many ways of being good at systems practice. Each systems thinker seems to be good in their own way. I believe this is because Systems is about ways of experiencing the world, ways of thinking, and about ways of dealing with the complex situations I encounter.

Consequently, systems expertise is unique to each person. I cannot tell you how it's going to work for you or how you should understand it. You have to find your own ways. All I can do is to invite you into experiences that are likely to help you create your own meanings from the material. As well as being the only logically consistent way of learning systems thinking, there is plenty of research evidence ‛For example, see Using Experience for Learning (Boud, D. Cohen, R. and Walker, D. (eds) 1993, Open University Press, Buckingham)” to show that understandings and knowledge that one acquires through discovery is retained and developed much more readily than the understandings one acquires through being told, or even shown.

Taking responsibility for your own learning in this way is challenging but it need not be difficult. It requires a preparedness to experiment with ideas and styles of learning that may not initially feel right or comfortable.

All this means learning Systems, as the course team understands it, is an intensely personal business. Don't worry if you're not used to reflective learning, you will be able to develop your capacities for learning this way, as you go. This is why it was important to think through what you want to achieve from the course. It can operate at a level beyond acquisition of skills and knowledge. Because it is about different styles of thinking, the process of thinking systemically can itself give rise to new forms of learning. It has the capability of bringing understanding into being from sources inside oneself. This is the process known as reflective learning.

For some people, systems thinking will be something they practice from time to time. It will be a set of tools-for-thought they use when the need arises. This is a powerful and important potential outcome from the course. The course can also lead you towards becoming systemic, as well as being about systems. You can use it to become a different sort of thinker.

Either way, I strongly urge you to tackle the activities. They are designed to enable you to discover your own learning by experience. They are much more important than practice-makes-perfect activities. They will support you in making systems thinking and systems practice your own. Without them, systems thinking and systems practice remain ‘out there’ – something you may know about (description) but not know how to use (competence). This course has aspirations beyond that, which I hope you will come to share; to support you in becoming a systems thinker and a systems practitioner. This is why the activities so far appear to be focused on you. You might see them in terms of preparing the soil in which skills, competencies and confidence can grow.

2.3 Appreciating epistemological issues

Common sense tells me my experience and understanding of the world are limited. I am 173 cm in height. That limits my view of the world. It may not matter much that I cannot see what my house looks like from above but it does mean there will be things going on in the roof I may not notice until they impinge on areas that I can experience.

More significantly, there is a real limitation on understanding the experiences of other people. You might tell me about your experience but your description is likely to be only a partial representation and, however good your description, I cannot share your experience. I can only construct my own mental representation of what your experience might be like. But the limitations on my understanding of the world are even more fundamental than this.

My mental image of the world is a model. It is a partial representation of reality based on the partial knowledge I have of the external world. So, when I think I am thinking about the world I am thinking about my model of the world. This model of the world is built up in a way that is itself a model. So I am using a model, built by a model, to represent the world I think I see.

This has important implications. The model that represents the world tells me what I see and tells me what to see. The model both limits what I see and reinforces itself. When I think about the world, I am thinking about my own thinking; I have no direct access to the world at all.

Many people find this idea unsettling when they first meet it. It seems to defy common sense. It raises the question of how real the so-called real world really is.

Many people think of the brain as very similar to a computer. Both have a similarly large proportion of ‘processors’ operating on internally generated signals. But there is an important and absolutely fundamental difference. The computer does not create its own meanings. The computer has no capacity for deciding, for example, which are its favourite paintings in the National Gallery. I do. I have a history of interacting with external stimuli that generate new ways of interacting with further stimuli and the internal structure of my brain changes as a result. The computer's ways of dealing with data are not the result of its own self-production. The way the computer works remains the same, whether it is processing pictures from the National Gallery or whether it is processing letters of the alphabet. The rules that relate input to output are constant over time.

The question of what I can know about the outside world is an ancient one and has always been central in philosophy under the theme of epistemology. Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that deals with knowledge and knowing: how do I know about the outside world? how do I know my senses are not fooling me? what constitutes evidence about the world?

Neither discussions about modelling, nor the insights of philosophy, can tell me how true my internal representations of the world are, but neurological studies seem to suggest the outside world is unknowable as it is. Epistemology is a central concern in the course from which this unit has been extracted. This contrasts sharply with many other courses where epistemology is never addressed. The world is assumed to be ‘out there’ and more-or-less as it appears.

Recognizing the world is unknowable as it is presents me with a choice. How do I deal with the day-to-day observations and events that seem to emerge from it? Each person, once they become aware of this unknowability, is confronted with, and needs to make their own choice.

Each choice is individual but seems to cluster around three main poles. The first of these is to adopt a stance that the world is more-or-less as I see it, and to ignore the incompleteness of my viewpoints and my representations. This is equivalent to saying ‘there is no epistemological problem about the world as I see it’. The second is to decide that the world is more-or-less as I see it but to recognize that my viewpoint is limited and the view-from-here may be misleading because it is only partial – there is no view of the roof, to use my previous metaphor. This is a stance that accepts that I must be careful to explore the world as fully as I can because I cannot see everything and may be misled. The third pole is to take on fully the implications of the world's unknowability. This stance demands that I always carry an awareness that I will never know the world and must therefore always be trying to account for my own role in my perceptions of the world. Consciously making the choice between these poles, and all the variants in between, is an act of epistemological awareness.

The choice one makes has profound implications for one's ranges of thought and action. Of course, knowing most of what I'm aware of is actually generated within my own brain does not mean I can make up any version of reality I choose. But it does mean I have to recognize my knowledge of, and understanding of, the world is partial and provisional and depends to a significant extent on my internal processes of constructing representations. This theme will come up repeatedly but for now it seems to suggest a number of attitudes or mental stances will be helpful.

Some of the mental attitudes I try to adopt are:

-

Being open and sensitive to all kinds of information about a situation: not just so-called factual information but impressions, intuitions and hunches, including other people's when they express them;

-

Being willing and able to see the situation from all kinds of points of view in addition to my own;

-

Being as open as I can be to seeing the situation and not letting my theories, presuppositions and assumptions tell me how I ought to see it;

-

Not taking terms of reference, boundaries or constraints too seriously; I try to assume they may not be as rigid as they seem to be;

-

Trying to find out how other people see the constraints and boundaries;

-

Being wary of any solution to a complex question (including my own solutions);

-

Enjoying diversity and complexity in a situation; resisting the temptation to discard inconvenient bits of information; paying more, rather than less, attention to awkward facts, impressions or ideas;

-

Not minding too much if there are areas of uncertainty in my understanding, or bits of information I don't have; being sceptical about the facts I do have.

Adopting a set of stances isn't necessarily easy so here are some suggestions about things you can actually do when you are looking at a complex situation that mystifies you in some way. (There are likely to be times when the course itself looks like a complex situation that mystifies you.) Practising these will help you to develop the open, enquiring style that can make systems work so exciting.

Make sure you include in your thinking about the situation:

-

The preceding history and the wider context of the situation;

-

Information about how people (including you) involved in the situation feel about it; what are the hunches, intuitions and suspicions they, and you, have about it;

-

Information about the dynamics (procedures, flows, communications, feelings) of the situation as well as the structure (roles, organization framework, boundaries, materials, components) and how the process and structure fit together;

-

Information about how the situation appears to other people, including those around the situation as well as those directly involved;

-

Attention to what is not going on and what is not present.

2.4 Review

In working through this section, you have identified some of your initial expectations and I have explained some of what I think you will discover as you work through the unit. It would be appropriate at this point to look at some of the questions I asked you about your expectations again and note ways your expectations have changed.

Spend a total of around 30 minutes on the next three activities.

Activity 6

Looking through your previous notes and my previous questions, identify and record any ways your expectations have changed.

Have any new expectations emerged from your reading of this new section? Do any of your expectations look less realistic now? Do your previous expectations seem more, or less, likely to be met?

Do you have any new ideas about what you would like to get from the course?

Activity 7

Do you feel able to adopt any of the attitudes I have suggested?

Most people move into and out of the attitudes I described earlier. The difference I am proposing is that you consciously try and adopt them as you improve your capacities as a systems thinker. Do you think these attitudes will be useful to you? Have you adopted them in doing this activity? How successfully? You may like to record some judgement about whether you like the idea of these attitudes. Notice that I referred previously to ‘a willingness to experiment with styles of learning that may not initially feel right or comfortable’. Does this reflect anything you are experiencing at this stage?

Activity 8

How do you understand the focus on your own responses in the activities and in the reading you have done so far?

Notice your intuitive responses as well as your intellectual responses. Are you puzzled? Stimulated? Surprised? Excited? Hoping it will get somewhere? Eager to find out more? Suspending judgement? Frustrated?

Any or all of these responses, even if they are a little difficult to live with, are likely to enable you to make good use of what comes in the rest of this block, and in the rest of the course.

It may also be you are unused to, or uncomfortable with, the focus on yourself and your own experience in an academic course. This need not inhibit your learning, provided you recognize your discomfort. If you stick with it, the unfamiliarity of this type of approach is likely to disappear. The payoff: you can become a person who can think and practice systemically. Without engagement with your self, Systems is likely to remain, for you, a collection of techniques that are never really your own.

It would be unreasonable for me to expect that you would instantly recognize this is an effective way of starting a course on Systems.

Make a note of your present understandings and responses.

3 Understanding systems approaches to managing complexity

3.1 Introduction

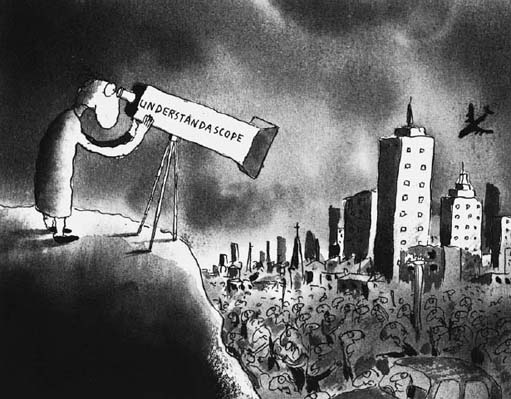

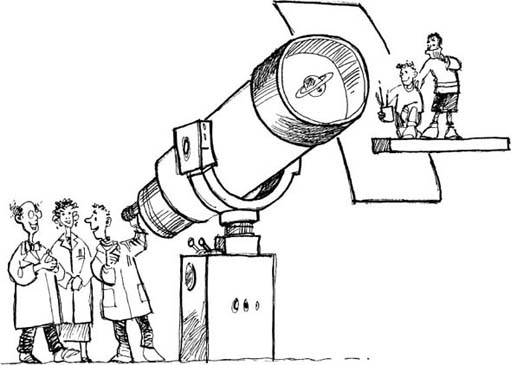

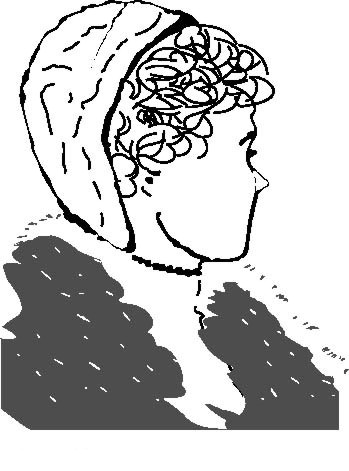

I wonder if you experience complexity in your daily life? For much of the time I struggle to keep my head above water as I try to understand and manage the complexity I experience as part of everyday life. I find social commentator and cartoonist Michael Leunig's depiction of a solitary figure looking through an ‘understandascope’ (Figure 2) a particularly skilled way of capturing the sense of bewilderment I sometimes feel. For the purposes of Sections 4–7 I am using his cartoon featuring the ‘understandascope’ because it raises a number of important questions relevant to my aims. Using Figure 2 as a metaphor, these questions are:

-

What is it about individual human beings that characterize how they observe the world? i.e. what are the properties of the observer looking through the understandascope?

-

How do humans engage with the world around them? i.e. what are the properties of the understandascope?

-

What sense do humans make of the world they experience? i.e. what sense is the observer able to make about the ‘messy’ sea of human activity that is being engaged with through the understandascope?

-

Does the observer stand outside the ‘messy’ situation being observed or do the properties of the ‘understandascope’ – the way in which s/he engages with the world – enable the observer to be an effective actor in it?

-

What new understandings does the observer have after engaging with the situation through the understandascope?

I use Leunig's cartoon as a means to introduce my ideal of a systems practitioner. As you work through this part of the course I want to invite you to imagine an ideal systems practitioner as a type of understandascope, as a lens through which to develop your own systems practice and to respond to the questions posed above. By ideal, I do not mean highly desirable. I am using the term in a philosophical sense meaning a set of ideas about, or a model of, a systems practitioner.

At the end of this course, my aim is that you will have a greater understanding of ‘systems approaches to managing complexity’. But what makes it possible to say ‘I understand someone or understand something about the world in which I live?’ Is there a state of mind or body that can usefully be referred to as understanding? By the end of this course our hope is to have provided the means to respond to the question: What is it that we would need to have observed, in others or in ourselves, for us to say that understanding systems practice had occurred? In the language of the cartoon I am asking you to envisage

-

yourself as the observer;

-

the ideal systems practitioner as the understandascope; and

-

the complexity you are trying to understand as residing in the relationship between the observer (you) the understandascope (your appreciation of systems practice) and the context (the messy situation depicted in the cartoon).

You might find it helpful to return to this part as the course goes on. This will enable you to see how the issues raised here are taken up in subsequent blocks from different perspectives.

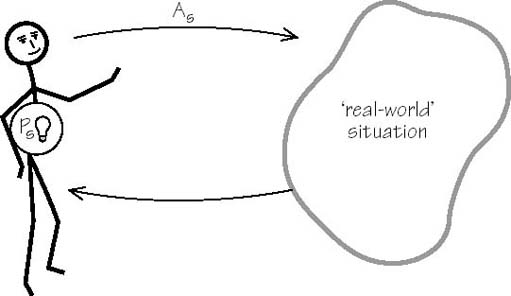

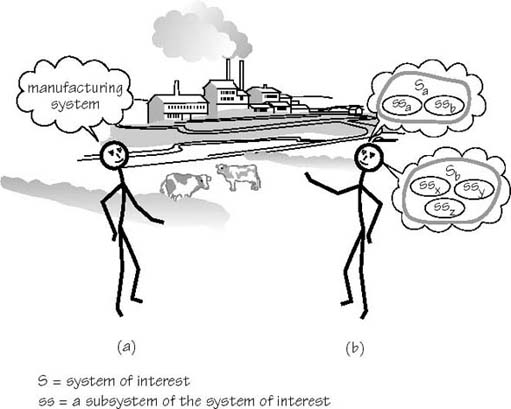

Figure 3 illustrates the general idea of a practitioner, P. I am using the idea of the practitioner as someone who engages with some so-called ‘real-world’ situation in practice, using selected approaches.

I am using the phrase ‘real world’ to distinguish from the conceptual world, the world of thinking. In many ways this is an artificial distinction because the world I perceive to be the ‘real world’ is, in fact, my own conceptual model. What I perceive is conditioned by my conceptual models. So for me the real ‘real world’, is unknowable. My desire is to change the question from ‘what is the world’ to ‘how do I know the world’. So every time I use the term ‘real world’ you should remember that this is a short-hand for the process of coming to know the world.

Later, I will introduce the idea of the systems practitioner who is a special case of the general practitioner. Figure 2 also depicts a form of practice – a person using an understandascope to do something.

In this course, the idea of practice, or practising, is a general one in that it is something everyone does. The dictionary definition of practise is ‘to carry out or perform habitually or constantly … to carry out an action’. Almost everyone has some role in which they practise. Most people occupy a number of roles, in their work or in their community. In these roles it is usual to encounter a number of issues that need dealing with, improving, resolving, or obviating. For example I am a practising father as well as a practising academic.

Activity 9

List some of the practices you engage in personally and professionally. Suggest some measures of performance for these practices, i.e. how do you know if you do them well?

Answer

For the purposes of this exercise I will refer to my practices as a father and as a researcher. I will use the following table to complete my answer.

| Practice | Measure of performance | How do I now if I do it well? |

|---|---|---|

| Fathering | Nature of communication with my daughter | We talk regularly and usually enjoy our conversations – my daughter gives me feedback and I listen (mostly!) |

| Emotional quality of our relationship | I feel loved and understand this is reciprocated | |

| Extent of mutual respect | Manifest through mutual engagement in each other's work/ideas | |

| Extent of trust | By my daughter never feeling the need to have my permission to do something and by the lack of actions that betray my trust | |

| Researching | Grants obtained | Am fully committed with a number of large grants in last three years |

| Papers published | Two per annum is target which I usually meet. | |

| Invitations to talk/participate | These continue to arrive. | |

| Extent of personal satisfaction | I enjoy myself when researching – but find admin distracts me | |

| Usefulness to others | More difficult – based on feedback and personal judgement |

It was much easier to think of measures of performance in my professional practice than in my personal practice. But on the other hand more is at stake, for me, in my personal practice.

It follows from the dictionary definition that a practitioner is anyone involved in practice – in carrying out an action. If I reflect on my own practice, I am aware that what I do is not as simple as the interaction between practitioner and situation portrayed in Figure 3. I experience myself as something of a juggler trying to keep a number of balls in the air as I practise.

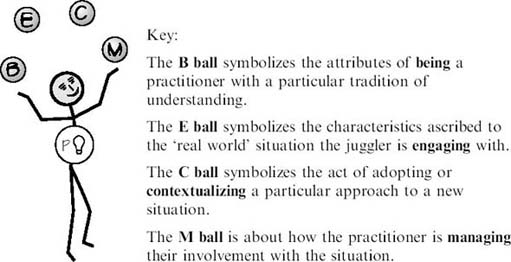

In this course we employ the metaphor of the systems practitioner as juggler and now I am going to focus on four particular balls we (the course team) think need to be kept in the air for any form of effective systems practice (Figure 4).

Based on my experience, I claim that effective practice involves being aware that these four balls need to be juggled – it takes active attention, and some skill, to keep them all in the air. Things start to go wrong if I let any one of them slip. To be an effective practitioner, I find I have to continuously think about, and act to maintain, four elements: the processes of being a practitioner, my appreciation of the situation I engage with, putting the approach taken into context and managing in the situation. The four verbs, the activities, I am drawing your attention to are being, engaging, contextualizing, and managing. The remainder of the course is structured around these four balls being juggled by a systems practitioner.

3.2 Making sense of the metaphor

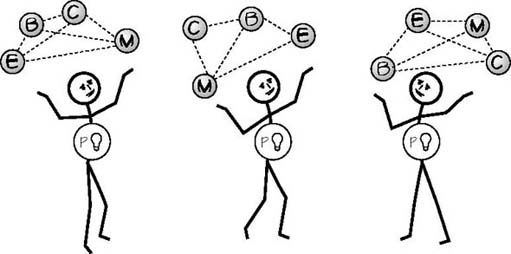

The metaphor of the juggler keeping the four balls in the air is a powerful way for me to think about what I do when I try to be effective in my practice. It matches with my experience: it takes concentration and skill to do it well. But metaphors conceal features of experience, as well as calling them to attention. The juggler metaphor conceals that the four elements of effective practice often seem to be related. I cannot juggle them as if they were independent of each other. I can imagine them interacting through gravitational attraction, or the juggler can juggle them differently e.g. the E and B balls with the left or right hand as depicted in Figure 5. This allows me to say that in effective practice the movements of the balls are not only interdependent but also dependent on my actions.

Activity 10

Write down your own initial impressions to the metaphor of the systems practitioner as juggler.

It might be helpful to explore what the metaphor reveals and conceals for you by relating it to one of the roles you have, or situations you have experienced. A spray diagram could be used.

4 Systems practice – unpacking the juggler metaphor

Systems practice, modelled in Figure 6, is a particular form of the general model of practice in Figure 3. An effective systems practitioner, Ps, is able to use systems approaches in managing complexity. I am not overly concerned with other approaches to practice, and will not be making any extravagant claims that a systems approach is better than other forms of practice. I will, however, develop arguments that enable me to make two claims.

-

Systems practice has particular characteristics that make it qualitatively different to other forms of practice.

-

An effective (or aware) systems practitioner (Ps) can call on a greater variety of options for doing something about complex ‘real-world’ situations than other practitioners do.

These are important claims. They will structure most of the argument made in the rest of the block.

I intend to build up a picture of an ideal systems practitioner in stages rather than attempting it in one go. Juggling is a set of relationships. A juggler is a person, or living human being, in a particular context, with their body positioned so as to be supported by the floor and in this case they have four different balls. If any of these things are taken away, the juggler, the connection to the floor or the balls then juggling will not arise as a practice. In some situations an audience might also be important, especially if juggling for money. Taking away the audience would destroy the ‘system’, the interconnected set of relationships being envisioned. But there's more to this set of relationships then meets the eye. Take the juggler for example: she or he is both a unique person and also part of a lineage of groups of organisms called living systems. All living systems have an evolutionary past and a developmental past that is unique to each of us – a set of experiences which means that my world is always different to your world. We can never truly ‘share’ common experiences because this is biologically impossible. We can however communicate with each other about our experiences.

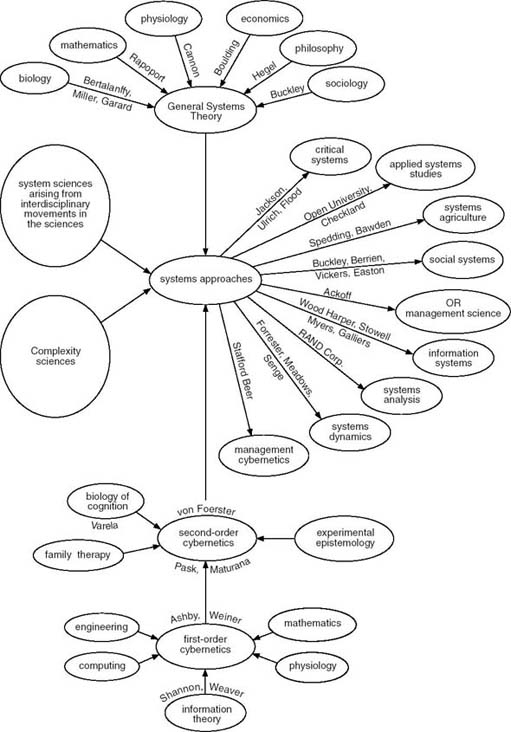

Many well-known systems thinkers had particular experiences, which led them to devote their lives to their particular forms of systems practice. So, within Systems thinking and practice, just as in juggling, there are different traditions, which are perpetuated through lineages (see Figure 7).

Activity 11

Tick off those blobs in Figure 7 which you have heard of or with which you are familiar.

Do a web search and bookmark some sites which relate to those blobs you have not heard about. Use any search engine to do this perhaps starting with the words or people named in the figure as key words. Some resources can be found on OU Systems websites.

Before finishing this introduction to the systems practitioner, I want to examine in more detail each of the balls being juggled.

The first ball the effective practitioner juggles is that of being. Juggling is a particularly apt metaphor in this regard because good practice results from centring your body and connecting to the floor. So juggling arises from a particular ‘disposition’ or embodiment. Effective juggling is thus an embodied way of knowing. Lakoff and Johnson (1999) argue that in the Western world, the most common sense view of what a person is arises from a false philosophical view, that of disembodied reason, that has influenced almost all of the professions. They contrast this with an embodied person (Table 1). For example in medicine until quite recently the brain was seen as quite distinct from the body – the mind-body dualism – whereas the brain is part of a much larger network that includes the nervous, endocrine and immune systems (e.g. Pert, 1997). It is for this reason that I have depicted the juggler with the light in their body rather than above their head. The light symbolizes embodied understanding.

Activity 12

List the two contrasting ideas from Table 1 that you find most challenging to, or supportive of, your current worldview. Explain why.

Answer

I think the last pair is the most challenging for me and others I encounter – not because I do not accept it on the basis of evidence emerging from over 30 years of cognitive science research, but because it is still difficult to talk about. My experience is that the majority of people take the traditional view so much for granted that the alternative is often dismissed before the conversation can begin. Recently my daughter's teacher responded in this manner in response to points she raised in an essay for her ‘theory of knowledge subject’ as part of her International Baccalaureate studies.

The second I find most challenging concerns ‘conceptual metaphors’. The research conducted by Lakoff and Johnson and others suggest that through our evolution we have acquired a predisposition to structure the world in certain ways – and one of the most basic ways we do this is when we form categories. Let me exemplify this by referring to what they call the ‘container metaphor’. One needs to think of this in terms of say a child's development from birth. For these researchers metaphors have an embodied basis, e.g. a child putting things in and out of any container is a basic experience; later this is internalized as in–out action patterns (‘container’ image schema) followed by literal language application of schema, e.g., ‘Out of the box’; ‘In my pocket’; ‘Out of the cup’; ‘In the fridge’. Then there is progressive metaphorical extension, e.g.

-

‘Go into the house’

-

‘I'm in bed’

-

‘I'm in her class’

-

‘They won't let me in their group’

-

‘Keep it in the family’

-

‘Within the terms of reference’

-

‘An outsider’

-

‘Exclusive restaurant’

-

‘In time’

-

‘In washing the window, I cracked it.’

-

‘There are lots of houses in London’

-

‘In love’

-

‘Let out your bottled up anger’

-

‘Fall into a depression’

-

‘I put a lot of energy into this’

-

‘Pick out the best theory’

-

‘I give up – I'm getting out of the race’

-

‘It finally came out that he had lied to us’

-

‘My kind of person’

The implication of this explanation is that we do not engage in a process of universal reason which is independent of our biological history.

Being is concerned with embodiment, with our own awareness and thus our ethics of action, the responsibility we take as citizens. How a practitioner engages with a situation is not just a property of the situation. It is primarily a property of the background, experiences and prejudices of being the practitioner. So, in the next section I will focus on some of the attributes of the practitioner. One of these attributes is awareness, awareness of self in relation to the balls being juggled and the context for this juggling. The nature of this awareness and what it means to be an aware practitioner will be explored.

The second ball is the E-ball – engaging with a ‘real-world’ situation. It is an engagement that can be experienced as messy and complex, or experienced as a situation where there has been a failure or some other unintended consequence. Or the ‘real world’ could be experienced as simple, or complicated or as a situation or as a system. Because I am primarily concerned with situations that are experienced as complex, I will call this engaging with complexity; later I will expand upon what I mean by complexity.

| Traditional Western conception of the disembodied person | The conception of an embodied person |

|---|---|

| The world has a unique category structure independent of the minds, bodies or brains of human beings (i.e. an objective world). | Our conceptual system is grounded in, neurally makes use of, and is crucially shaped by our perceptual and motor systems. |

| There is a universal reason that characterizes the rational structure of the world. Both concepts and reason are independent of the minds, bodies and brains of human beings. | We can only form concepts through the body. Therefore every understanding that we can have of the world, ourselves, and others can only be framed in terms of concepts shaped by our bodies. |

| Reasoning may be performed by the human brain but its structure is defined by universal reason, independent of human bodies or brains. Human reason is therefore disembodied reason. | Because our ideas are framed in terms of our unconscious embodied conceptual systems, truth and knowledge depend on embodied understanding. |

| We can have objective knowledge of the world via the use of universal reason and universal concepts. | Unconscious, basic-level concepts (e.g. primary metaphors) use our perceptual imaging and motor systems to characterize our optimal functioning in everyday life – it is at this level at which we are in touch with our environments. |

| The essence of human beings, that which separates us from the animals, is the ability to use universal reason. | We have a conceptual system that is linked to our evolutionary past (as a species). Conceptual metaphors structure abstract concepts in multiple ways, understanding is pluralistic, with a great many mutually inconsistent structurings of abstract concepts. |

| Since human reason is disembodied, it is separate from and independent of all bodily capacities: perception, bodily movements, feeling emotions and so on. | Because concepts and reason both derive from, and make use of, our perceptual and motor systems, the mind is not separate from or independent of the body (and thus classical faculty psychology is incorrect). |

The third ball is concerned with how a systems practitioner puts particular systems approaches into context (i.e. contextualizing) for taking action in the ‘real world’; that's the juggler's C ball. One of the main skills of a systems practitioner is to learn, through experience, to manage the relationship between a particular systems approach and the ‘real-world’ situation she or he is using it in. Adopting an approach is more than just choosing one of the methods that already exists. This is why I use the phrase ‘putting into context’, to indicate a process of contextualization involved in the choice of approach.

The final ball the effective practitioner juggles is that of managing (the M ball). This is concerned with juggling as an overall performance. The term ‘managing’ is often used to describe the process by which a practitioner engages with a ‘real-world’ situation. This is a special form of engagement, so later I will explore some of the features associated with managing. Managing also introduces the idea of change over time, in both the situation and the practitioner.

There are clearly many ways in which being, engaging, and contextualizing are carried out, or could be carried out. Thus, when considering managing I shall be concerned with managing the juggling in ‘real-world’ situations experienced as complex.

I would urge you to keep Figure 6 and the juggler metaphor in mind when you are answering questions because a competent answer will always refer to the relationship between practitioner (you and your being), the approach you are envisaging given the nature of the situation as you and other stakeholders perceive it (i.e. your mode of engaging with a situation of interest), how you envisage adapting your practice to the circumstances (contextualizing) and how you plan to manage the overall activity.

5 Being a systems practitioner

5.1 The state of ‘Being’

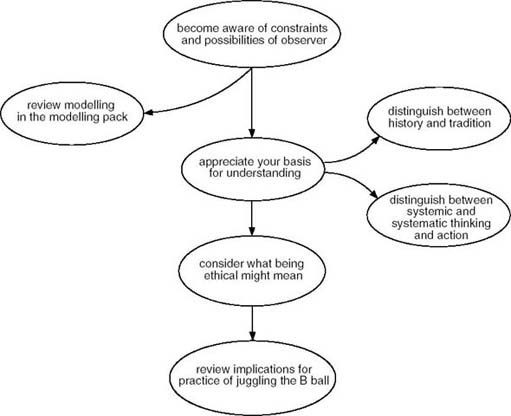

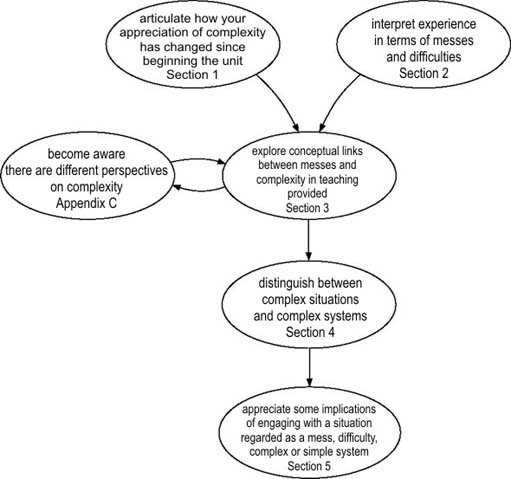

The structure of Section 5 is set out in Figure 8. Use this as a way of keeping track of the argument I am making.

Activity 13

Develop a table in your notebook with three columns. Put the verbs from each of the blobs in Figure 8 in one column. Jot down what they mean to you now in the next column and, at the end of your study of this section, jot down how your understanding has changed, if at all, in the third column.

I am concerned with the juggling of the B ball in this section. As I write, I imagine this ball is shiny and thus acts as a mirror reflecting an image of the juggler. The properties of the juggler as systems practitioner come under the spotlight in this section. In choosing the word ‘being’ I am deliberately playing, metaphorically, with different meanings of being – one of which is, of course, ‘human being’. Some of the special features of being human include consciousness, language, emotions, and the capacity to reason or rationalize. It is also claimed that human beings live with a desire for explanations they find satisfying. You may have had the experience of a child repeatedly asking why?, how?, and then stopping after you have given a particular answer. The child finally finds your explanation satisfying – it makes sense within the child's world – and the child no longer needs to ask.

Perhaps you have experienced explanations that did not satisfy at all. If you are aware of this occurring did you note what it felt like? By this I mean, were you in touch with your emotions when you became aware that a particular explanation was satisfying or dissatisfying? By asking this question, I am saying it is legitimate to acknowledge your emotions – they are part of living and need not be ignored. I would go further and argue that an ideal systems practitioner is able to include an awareness of their emotions as well as their rational ideas. I find my Systems practice is enriched when I am able to access both.

5.2 Being aware of the constraints and possibilities of the observer

It is often claimed that the essence of a systems approach is that of seeing the world in a special way. This immediately prompts the question of what is meant by the phrase ‘seeing the world’. Because we live so intimately with the world of objects, categories and people and phenomena, we tend to think our own way of seeing the world is the only way, or even of thinking, ‘Well that is my view because the world is like that’. Actually, your view is special in several separate ways.

-

If your vision is not impaired, you see your surroundings using only light of wavelengths between 380 nm and 780 nm (nanometres or 1×10−9 m). Bees, for example, see flowers using wavelengths less than 380 nm. You have quite a small visual window on the world.

-

Research on colour perception in the 1960s showed that colour was not something that is fixed in the world, but is a property of our own unique histories. This led one of the researchers involved to change the question he was concerned with from ‘how do I see colour’? to ‘what happens in me when I say that I see such a colour?’

-

With normal hearing you hear frequencies of sound between 20 Hz and 20,000 Hz (Hertz). Bats use sound waves of higher frequency than 20 kHz, which we cannot hear.

-

Your ability to detect odours is vastly inferior to a dog's. A dog's ‘smell world’ is vastly richer than its visual world.

-

The language you have learned steers you into categorizing your world in ways you are largely unaware of, just as a fish is unaware of the water it is immersed in throughout its life. Sometimes it is possible to become aware of this when speaking another language – when immersed in the other language the experience is sometimes like being a different person.

-

Your physiological state and the dynamic relationship of this with your emotional state also affect how you experience the world. This ranges from aspects of the functioning of your nervous system and its role in cognition, to hormonal events such as menstruation, and the release of natural endorphins during exercise.

-

The culture of the society in which you have developed has determined what you see as well as how you can respond in any flow of relationships. Your culture determines what is implicit in your perceptions and emotions. So the ways you see manners, relationships and behaviours is dependent in turn on how people around you see and act.

-

A special subset of the last point is the particular explanations we accept for things we experience. The ‘theoretical windows’ through which we interpret and act are always with us regardless of whether we are aware of them or not. Figure 9 provides a metaphorical account of this phenomenon. The theory or explanation you accept will determine what you see and thus the meaning you will give to an experience. Think here, for example, of the fundamentally different cosmology, the set of explanations for the origin and evolution of the universe, developed by the Mayan civilization in South America that was entirely coherent but so different to Western cosmology. This is sometimes described as the theory dependency of facts.

Activity 14

Checking out your own capacities as an observer.

Even now, your mind set – the way you see things – can be easily influenced. To see how this statement is true follow the instructions carefully.

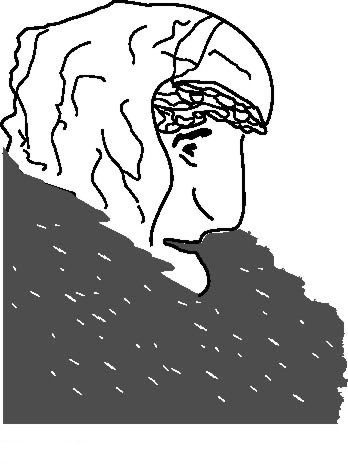

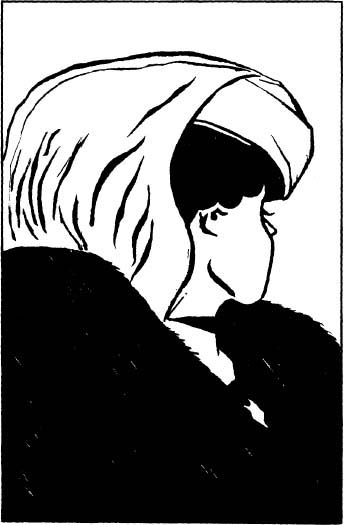

If your last name begins with a letter between A to M, look carefully at Figure 10. Then look carefully at Figure 12.

If your last name begins with a letter between N to Z, look carefully at Figure 11. Then look carefully at Figure 12 .

Discussion

If you are an A-to-M, you probably saw the young woman, and if you are an N-to-Z, you probably saw the old woman. Tests of these pictures, done with groups of students, show that prior influence is always powerful. This activity raises two important questions.

-

What is experience? In this example some people experienced a young woman whilst others experienced an old woman yet both looked at the same image. This leads me to claim that experience arises by making a distinction – if you are unable to distinguish a young woman then you have no experience of one!

-

Is it possible to decide on which interpretation, the young woman, the old woman or merely the ink on the paper, is correct? In other words do we reject those people who see only an old woman as being ‘wrong’?

On the basis of doing Activity 14 try the next activity. Spend no more than about 10 minutes on it.

Activity 15

When you talk about experience what do you mean?

Describe what was, for you, a new experience.

Discussion

For me the following story was helpful in making sense of what I mean by experience. I had the good fortune to do a consultancy in South Africa just after the first multi-racial elections. It was a time of goodwill and enthusiasm and general optimism. An incident happened towards the end of a flight from Johannesburg to East London in the new province of the Eastern Cape.

As the plane taxied up the tarmac towards the terminal, I experienced my South African colleague, in the seat next to me, as becoming agitated and tense. Looking out the window, as he was, I could not distinguish anything that I could see as the cause of his distress. When I enquired, he pointed to some seemingly innocuous cement pillars, which he explained were the remains of gun emplacements left over from the state of emergency in the apartheid era. Because of his history, which was different to mine, he had seen what I could not see, that is his observation consisted of distinctions that I had not made. Furthermore, the distinctions my colleague made altered his mental, emotional and physiological state – they altered his being. My colleague made distinctions I was unable to make and thus he experienced something I did not.

The act of making a distinction is quite basic to what it is to be human. When we make a distinction we split the world into two parts: this and that. We separate the thing distinguished from its background. We do that when we distinguish a system from its environment. (Remember, using the word system is actually shorthand for specifying a system in relation to an environment.) In process terms, this is the same as drawing a circle on a sheet of paper. When the circle is closed, three different elements are brought forth at the same time: an inside, an outside and a border (in systems terminology, a boundary). In daily life we have developed all sorts of perceptual shortcuts that cause us to forget this is what we do – we live, most of the time, with our focus on one of these three elements: the inside, the outside, or the border. Biologically, we cannot focus on both sides of a distinction at the same time. Heinz von Foerster (1984) observed that the descriptions we make say more about ourselves than about the world we are describing.

While the old woman-young woman example is now well known, the implications that flow from it are not. The activity, and the points listed prior to that demonstrate that in the experience we cannot distinguish between perception and illusion and that ‘we do not see that [which] we do not see’ (Maturana and Varela, 1987). It is ironic that we pay money to go and see illusionists, and marvel at their artistry, yet remain unaware that illusion is also part of daily life. For systems practice this idea is challenging in a number of ways:

-

It draws my attention to what is involved in the process of modelling, of which diagramming is a subset. It raises the question of whether we model some part of the world or model our models of some part of the world.

-

It challenges the certainty of some practitioners who claim they are objective or they are right, and because of this, affects the way they practise.

-

It reminds me that my perspective is always partial and a product of my cognitive history (I would include emotions as part of a cognitive history). Thus, when forming a system of interest, the question of ‘perspective, who's perspective?’ is crucial.

-

It reminds me to be aware of the constraints and possibilities of the observer as I juggle the B ball in my practice.

The properties and role of the observer have been largely ignored in science and everyday culture despite Werner Heisenberg's finding in 1927 that the act of observing a phenomenon is an intervention that alters the phenomenon in ways that cannot be inferred from the results of the observation. This is the essence of Heisenberg's uncertainty principle, which limits the determinability of elementary events (von Foerster, 1994). The story of how the observer came into focus is an interesting one in the history of Systems and its associated field of cybernetics. Lloyd Fell and David Russell (2000) describe it in Box 1; its lineage can be seen in Figure 7.

Box 1 How the observer has come into focus

Cybernetics, although often applied to the control of machines, has long been one of the foundations of thought about human communication, its central notion being circularity. Cybernetics ‘arises when effectors, say a motor, an engine, our muscles, etc., are connected to a sensory organ which, in turn, acts with its signals upon the effectors. It is this circular organization which sets cybernetic systems apart from others that are not so organized’ (von Foerster, 1992). In first-order cybernetics it was the idea of feedback control which mainly occupied the practitioners, but in time the question ‘what controls the controller’ returned to view (Glanville 1995a,b) and the property of circularity became the focus of attention once again.

Second-order cybernetics is a theory of the observer rather than what is being observed. Heinz von Foerster's phrase, ‘the cybernetics of cybernetics’ was apparently first used by him in the early 1960s as the title of Margaret Mead's opening speech at the first meeting of the American Cybernetics Society when she had not provided written notes for the Proceedings. [The understandings which have arisen from second-order cybernetics…] requires a loosening of our grip on the supposedly certain knowledge that is acquired objectively, about a reality existing independently of us, and a willingness to consider the constructivist idea (see Mahoney, 1988) that we each construct our own version of reality in the course of our living together. The virtue of objectivity was that the properties of the observer should be separate from the description of what is being observed. This led to what von Foerster (1992) called the Pontius Pilate attitude of abrogating responsibility because the observer is an innocent bystander who can claim he or she had no choice. The alternative attitude, which seems to be less popular today, is to own a personal preference for one among various alternatives.’

Being aware of the constraints and possibilities of the observer enhances our repertoire of behavioural responses. Because we are able to communicate with one another, and because we live within cultures we can take shortcuts: it makes sense sometimes to act as if we are independent of the world around us. Sometimes it also makes sense to act as if systems existed in the world and as if we could be objective. But remember, the two small words as and if are important in the context of our behaviour when we attempt to manage. From the perspective developed in this section, it is always a shortcut when we leave them out.

5.3 Appreciating your basis for understanding

In my experience, the explanation that Fell and Russell suggest (i.e. that we each construct our own version of reality and therefore cannot be an objective observer; which in turn means we have to take responsibility for our observations and explanations) is challenging for many people. When I attend workshops where these ideas are expressed for the first time, people often become angry. You may be able to identify with them. If so, please try to use your discomfort productively for your own learning. It is profoundly disturbing to have the basis for your understanding of the world challenged. It seems important to do it, however, because in my experience, it gives access to new and practical explanations. I have already acknowledged you may find some explanations dissatisfying but, in the end, that is all they are – just explanations. If you don't find them satisfying you need not accept them. Just the same, I invite you to look at them for a while before dismissing them.

Activity 16

Responding to the distinctions about the observer.

Find a way of expressing your emotional and rational responses to the material in Box 1 about the observer. One way could be to use your notebook to record these.

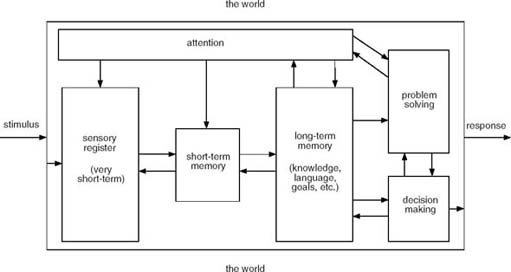

Relatively recent findings in cognitive science (e.g. colour perception), which are not widely appreciated, challenge some widely held ‘common sense’ notions. Take information for example. Many people assume that individuals would be better decision makers if they had better information. But how do we gain this information?

Since about 1950, the prevailing view in cognitive science has been that the nervous system picks up information from the environment and processes it to provide a representation of the outside world in our brain. This has been described as the information-processing model of the mind (Figure 13). We now know that the nervous system is closed, without inputs or outputs, and its cognitive operation reflects only its own organization. Because of this, we are imposing our constructed information – or our meaning – on to the environment, rather than the other way around. This is much like Figure 9, except this time the pattern of the planet is contained in our nervous system rather than the lens of the telescope. It implies our interactions with the ‘real world’, including other people, can never be deterministic; there are no unambiguous external signals.

Instead, our interactions consist of non-specific triggers, which we each interpret strictly according to our own internal structural dynamics (Fell and Russell, 2000). This has profound implications for how human communication is understood – it is not signal or information transfer but a process of meaning construction much as depicted in Figure 14 (but note, it is never shared as this cartoon depicts). Within this line of reasoning it is argued that we human beings exist, and are realized as such, in conversations. It is not that we use conversations; we are a flow of conversations. It is not that language is the home of our being but that the human being is a dynamic manner of being in language, not a body, not an entity that has an existence independent of language, and which can then use language as an instrument for communication.

For example when the word nature is used in modern Western discourse it is often used in such a way that leads us to live as if we human beings are outside nature. The concept ‘nature’ thus structures who we are and what we do. In some indigenous, non-western languages the term or concept does not exist. Obviously, this view has implications for what we mean by communication within systems practice.

The notion that we exist in language and co-construct meaning in human communication, much as dancers co-construct the tango or samba on the dance floor, suggests the need to consider on what basis we might accept that understanding has occurred. Asking this question is like opening a Pandora's box. It raises all sorts of questions that we take for granted, like: What is learning? What is understanding? How do we know what we know? Some of these questions are addressed in the next sub-section.

5.4 Experience – making distinctions based on a tradition and constructing a history

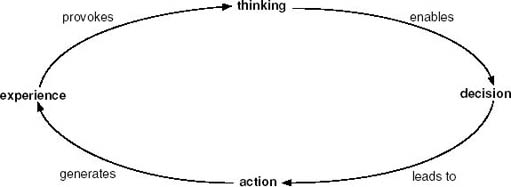

Experience, and learning from experience, will be a major theme throughout this course. The model of experiential learning developed by David Kolb is increasingly well known and used as a conceptual basis for the design of all sorts of processes from curricula to consultancies (Figure 15). In itself, the model is powerful but it does not address what is meant by experience or learning. In what follows, I want to provide a brief account of what these could be taken to be. My explanation is not mainstream, but arises from an appreciation of the constraints and possibilities of the observer described earlier and from the lineage labelled as second-order cybernetics in Figure 7.

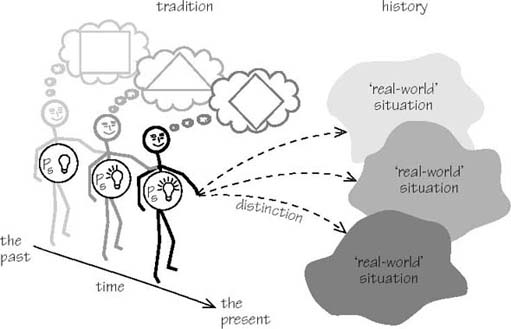

Figure 16 depicts a person (a living being) over time; as unique human beings we are part of a lineage and our history is a product of both ontogeny, which means biological growth and development, and social development. Together these form what I will call a tradition. A tradition is the history of our being in the world. Traditions are important because our models of understanding grow out of traditions. The various shapes in the clouds above the practitioner's head in Figure 16 are used to depict how our model(s) of understanding change over time. The lightbulbs depict how, over time, we can become more aware of our embodied understandings, which in turn influences systems practice.

I have portrayed ‘a practitioner’ with a prior model of understanding and a current model of understanding in Figure 16. From their current model(s) – it need not be one – the systems practitioner connects with a ‘real-world’ situation and makes a distinction. Based on this distinction, the practitioner can probe, or construct, the history of a situation.

Figure 17 is a refinement of the processes of being and engaging. I have now used the word tradition a number of times, including in Figure 17. I use the word in a specific way. I will call a tradition our history of making distinctions as human beings. Because experiences arise in the act of making a distinction, another way of describing a tradition is as our experiential history. To do this requires language – if we did not ‘live in’ language we would simply exist in a continuous present not ‘having experiences’. Because of language we are able to reflect on what is happening, or in other words we create an object of what is happening and name it ‘experience’