Managing complexity: a systems approach – introduction

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 25 April 2024, 10:52 PM

Managing complexity: a systems approach – introduction

Introduction

This course aims to develop skills of thinking systematically and creatively about issues of complexity. It enables you to appreciate and manage these issues in ways that can lead to improvement. It adopts the most recent and innovative advances in systems thinking and applies them to topical areas of concern. It is designed to help build your capacity to manage complexity and to develop a deep understanding of contemporary systems thinking. It may be helpful to study OpenLearn units T551_1 Sytems thinking and practice and T552_1 Systems diagramming before tackiling this unit.

This unit is from our archive and is an adapted extract from Managing complexity: a systems approach (T306) which is no longer taught by The Open University. If you want to study formally with us, you may wish to explore other courses we offer in this subject area.

Learning outcomes

At the end of this free course you should be able to:

use reflection to understand some of your own preferred styles of working

draw a systems map, review it, and use it to prompt further questions

evaluate your diagramming skills

develop, and take responsibility for, your own understanding of complexity

appreciate some ethical implications of being a systems practitioner.

1 Overview of the unit

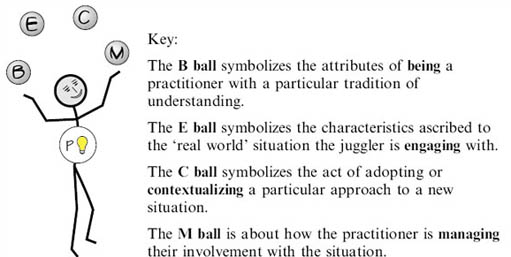

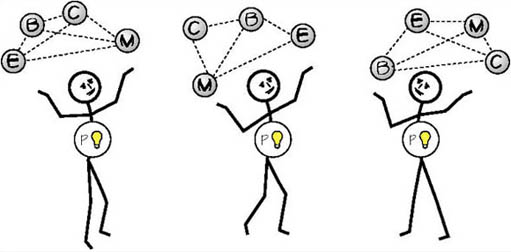

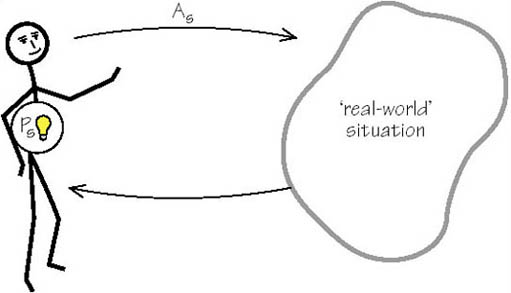

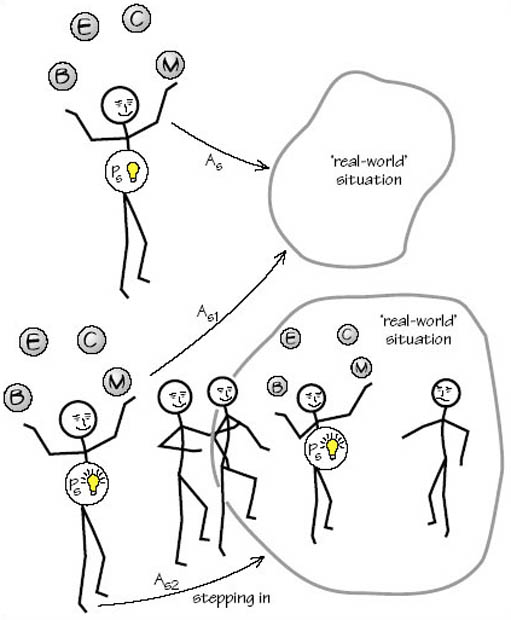

When you meet with a situation you experience as complex you need to think about yourself in relation to the process of formulating a system of interest. Only with this awareness, can you increase your range of purposeful actions in the situation which are ethically defensible. To do so is the hallmark of systemic thinking and practice compared to systematic thinking and practice. The metaphor of the systems practitioner as a juggler of four balls is introduced as a device to explore skill development for effective systems practice – the balls are being, engaging, contextualising and managing.

Part 1 Starting the course

To start, you will be invited to think carefully about yourself in relation to the course itself – as an introduction to thinking about yourself in relation to any system you devise.

Part 2 Experiencing complexity

Next, presented with a situation you experience as complex, you will be offered powerful systems-thinking tools for devising systems of interest that will support you in making sense of the situation.

Part 3 Understanding systems approaches to managing complexity

You will then be invited to consider your own role in becoming a systems practitioner through the lens of an ideal model and the metaphor of the systems practitioner as juggler.

Part 4 Making sense of your experiences of complexity

At the end of the unit, you are invited to reflect on the sense you have made of systems practice and ‘managing complexity’ together with your own role in making this sense.

2 Part 1 Starting the unit

Welcome to T306_2 Managing complexity: a systems approach – introduction. As I write, I experience a sense of excitement. For me, as for you, this is the beginning of the unit. These are the first few sentences I'm writing and so, although I have a good idea of how the unit is going to turn out, the details are by no means clear. Nevertheless, the excitement and anticipation I, and maybe you, are experiencing now is an important ingredient in what will become our experiences of the unit.

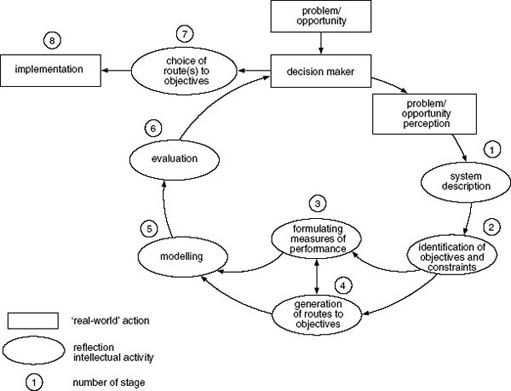

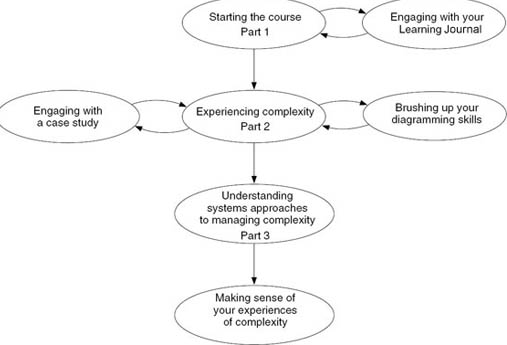

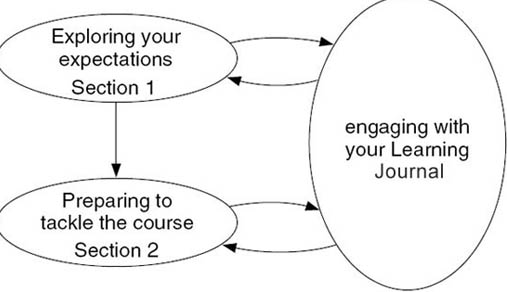

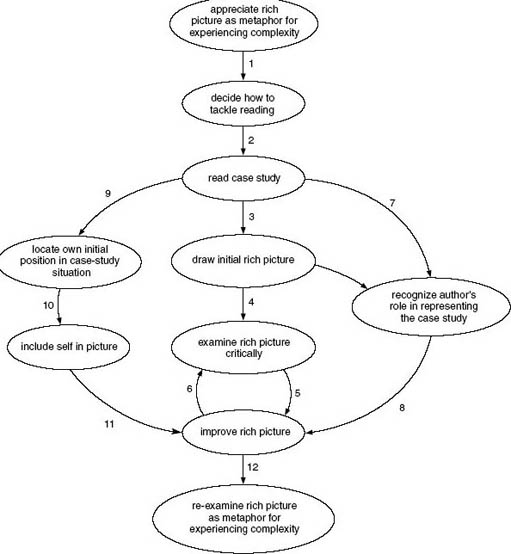

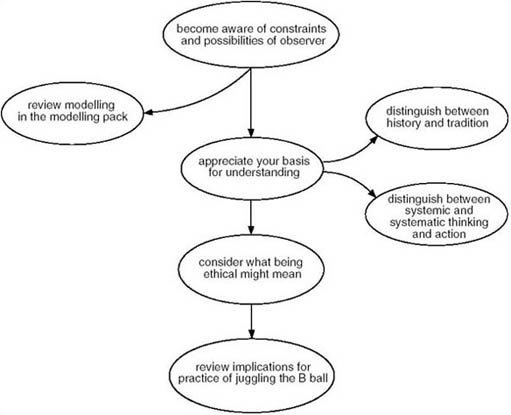

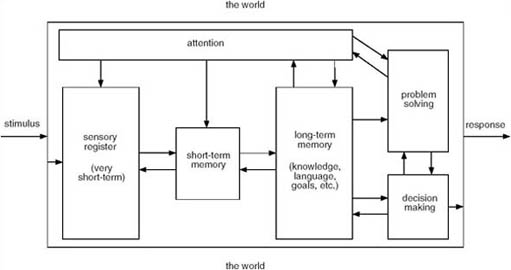

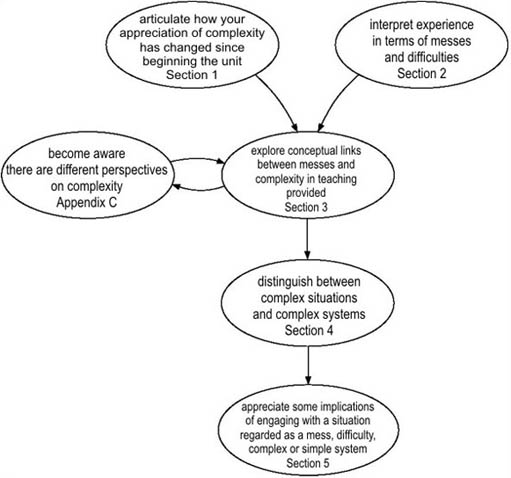

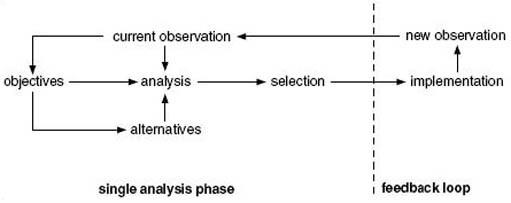

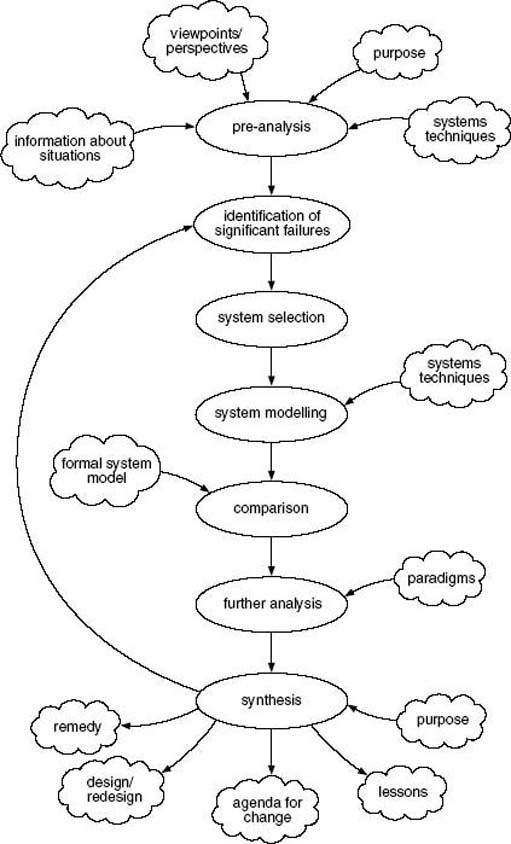

The structure of the unit is illustrated in Figure 1. You will find a number of activity-sequence diagrams in this unit. In an activity-sequence diagram activities at the pointed end of the arrows can only happen after the activity at the other end of the arrow has been completed. The sequence of activities for Part 1 of this unit is shown in Figure 2.

3 Part 1: 1 Thinking about expectations

3.1 What are you hoping to learn?

Anticipations and preconceptions are an important determinant of how people learn, so before you read on, I would like to you to record some of what you are experiencing now as you begin the course.

It's important to get these impressions noted down now, because new ideas and new impressions will quickly overlay the experience. What you are experiencing now will be re-interpreted as new understandings emerge. You are also likely to form some judgements about your expectations. So before any of that can happen, make some notes on your responses to the questions in the activity below. I suggest you make your notes in your Learning Journal. You will need to keep referring back to them as the unit progresses. It will also be helpful later if, as you make notes, you date them and leave space for later thoughts and jottings.

The notes you make for this, and some of the other activities, will be important so you should do them as conscientiously as possible. Their role in developing your skills will become more evident as you work through the unit. Your notes should capture as many elements of your responses as possible.

I anticipate you might spend around 90 minutes on this activity. It may take longer. This may seem like an enormous amount of time, but thinking about the issues carefully is likely to take that long.

Your Learning Journal will be an important resource for your study of this unit.

Activity 1

What is your purpose in doing this unit?

What do you hope to get from the unit? I imagine you might have some expectation that you will enjoy, or benefit from, doing the unit. What benefits do you expect? What was it in what you heard about the unit that suggested you might benefit from it? What was it about the unit or its descriptions that appealed to you? What is it about you that the unit appealed to? Not everyone chooses to study this unit so there must have been something about you that connected with what you heard, or read, about the unit. Make a note of any specific items that appeal to you. Make a note too of any items that worry or concern you.

What is your emotional state as you approach the unit?

Are you excited, bored, eager, puzzled, expectant, tired? What is your present body posture? Does it tell you anything about how you feel? Is it right? Can you improve your physical comfort?

Are you comfortable with your workspace? Are there things you can do to improve it?

You may be aware there is a project as a part of this unit: what anticipations do you have about doing the project?

Again, I imagine you might have some expectation that you will enjoy or benefit from working on material of your own choosing, or perhaps not. How do you feel about the prospect of the project?

What sort of skills and capacities do you think you might need for the project? How many of these do you have already? What skills will you need to pick up? What will you need to look for in the unit to acquire these skills and capacities?

And finally, how do you rate your overall capacity to succeed in this unit?

You first need to decide what, for you, would constitute success. Are there other criteria important to you? What are they? When will success become apparent?

How does your answer compare with your notes on what you hope to get from the unit? Are they congruent or does the answer to this question throw new light on what you hope to get from the unit?

When you make a judgement about how you rate your capacities, what are you basing it on? Are you taking account of external factors such as the time you have or the circumstances in which you study? Are you basing your judgement on your own evaluation of your intellectual capacities? Do energy, enthusiasm and commitment come into the evaluation?

What would it take to improve your prospects of success, measured by whatever criterion is important to you? Can you act to improve your chances of success?

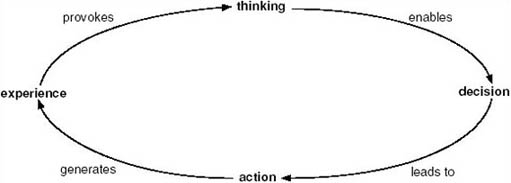

The activity you have just engaged in is the first of several such activities. It is an example of a pattern of activities that constitute reflective practice or reflective learning. This style of learning is based on the notion that the understandings most useful to us, and that most readily become part of us, are learnt by experience. The activities are designed to enable you to discover your own learning by experience.

There will be a lot about reflective practice in this unit but for now I want to introduce you to some basic ideas about it.

3.2 Learning by experience

It's a familiar idea but it implies two activities: learning and experiencing. Both activities need to happen if I am to say that learning from experience has happened. Experiencing seems to have two components. The first is the quality of attention that allows me to notice the experience and its components. The second is memory. Calling experience to mind allows me to examine the experience and to think about it in ways that were not possible at the time. Learning is what I take away from that process that influences my behaviour or thinking in the future.

But huge amounts of experience escape without being consciously experienced; I am insufficiently aware at the time to notice what's going on. Later I am too busy to recall the experience and so little conscious learning takes place. Of course, it's useful to carry out familiar activities ‘on auto-pilot’ – without conscious attention. It's easy to miss out on important learning from unfamiliar activities too. I may become wrapped up in the activity itself or simply not notice the range and quality of the experience. Either way, a conscious attempt to recall the experience and to think about it, gives the opportunity to learn from the experience.

So, what was my purpose in asking you to do Activity 1? I wanted you to experience the starting of this unit as richly as possible. I was asking questions that I hoped would prompt you into awareness of what you were experiencing. It may be you discovered something new about yourself; your expectations of the unit; what you hope to gain from studying it; or about your capacity to succeed in it as a result. If not, don't worry. The point of the activity was raising awareness rather than discovery; and recording material that will be useful in future learning and reflection.

Spend a total of about 15 minutes on the next two activities.

Activity 2

What do you understand the unit title to mean?

The title of this unit is Managing complexity: a systems approach. Before you go any further, and so your Learning Journal contains a record of your starting point, make notes about what you understand by the term ‘managing complexity’.

What do you understand by a systems approach? Don't worry if you feel you only have vague ideas at this stage, record all your ideas as fully as you can by listing all the things you think it might mean. You may also wish to distinguish ideas you feel confident about from those you are not sure of.

Activity 3

Add any further thoughts about your expectations.

You may feel some of the expectations you had have already been changed. Add any postscripts about this to the notes you made earlier. Make it clear in your notes these are postscripts and what has happened to change your views.

This is an advanced level Systems unit. This carries certain implications about its level and its likely content. You are likely to have drawn some conclusions about what these implications are. Recognising explicitly the presuppositions and assumptions you carry into a situation allows you to examine them. Presuppositions can get in the way of understandings. For example, if I assume a book is just about koalas, and don't notice it's about koalas in their eucalyptus habitats, I am quite likely to experience the text about eucalyptus forests as a distraction. This might lead me to misunderstand what the text is saying about eucalyptus habitats and, almost certainly, I would misunderstand its importance to the koalas. At the very least this will make me an inefficient reader and may make me an inefficient learner.

The next activity will help you to think through your expectations, assumptions and presuppositions about this unit.

Allow yourself about 30 minutes to do Activity 4, making notes as before.

Activity 4

What activities do you expect to undertake in studying an advanced level unit?

You may already have some experience of Open University courses. You may have other experiences of studying. What sort of activities do you expect to engage in when you study a course? What sorts of activities have in the past been most effective in enabling you to learn? These questions are easier to answer if you think back to a specific course or other learning experience. What did you actually do? What were the components of that course? What was their relationship to each other? If you have studied only intermediate level courses before, what differences do you expect in an advanced level unit? If you have studied at an advanced level before, can you identify any differences between those courses and other, lower level courses?

Which components of your previous learning experience have you enjoyed most? Why?

Some people enjoy the initial meeting with new material most. Others enjoy testing their newly acquired understandings in exercises. Still others enjoy their new perspectives on things quite external to the course that their new understandings give them. Do any of these match your previous experience? If not, what was it for you? You may also like to explore the question of what you didn't like. Have you changed in ways that might make your experience of this unit different?

What were you, as the student, expected to do as you worked through previous courses?

Many courses follow a fairly steady pattern of a bit of theory, followed by an example of what the theory means in practice, followed by an exercise where the learner applies what they have just learned to another situation. Do you recognise this pattern? Have you experienced it? Have you experienced variations on this theme? What were they? Have you experienced alternative approaches? How successful have these patterns been for you? Success, in this sense, might mean examination success or it might be a success criterion you have set yourself, or one you want to apply now. It may parallel the criteria for success you identified for this unit.

4 Part 1: 2 Preparing to tackle this unit

4.1 Something different

Perhaps it will not surprise you if I say you may experience this unit as rather different to any you may have previously encountered. Like any course of study, you are likely to find surprising and interesting material in it but there are three specific ways this unit may surprise and even challenge you. These three ways are concerned with:

The nature of systems thinking and systems practice;

A style of learning where you have to take most of the responsibility for your own learning;

The way you know about the world; interpret information about it; and construct mental models. These are epistemological issues. The bases for knowing about, and acting in, a situation is different to that encountered in most other units with a ‘T’ (technology) code.

Each of these will be discussed briefly below.

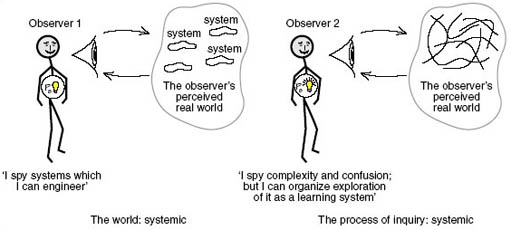

2.2 The nature of systems thinking and systems practice

There are no simple definitions for either systems thinking or systems practice. It's difficult to find definitions that capture all the perspectives that the ideas carry for people who think of themselves as systems thinkers and systems practitioners. Most systems practitioners seem to experience the same kind of difficulty in explaining what they do or what it means to be systemic in their thinking. Through experience I've developed some criteria by which I characterise systems thinking, but they seem to be quite loose in the sense that those characteristics are not always observable in what I recognise as systems thinking. In any case, they seem to be my list of characteristics, similar to, but not the same as, other people's lists. This issue will be developed but, for the moment, I would like you to hold the idea that systems thinking and systems practice arise from particular ways of seeing the world.

My hope is, through interacting with the course and asking yourself questions about your experiences, you will discover at least some of these characteristic ways of seeing the world. If you have previously studied Systems courses, you will already have experienced forms of systems thinking and perhaps ‘caught’ it in some way. You may even have developed your own understanding of systems thinking and what it means. If you have not studied Systems before, you need to be aware this unit cannot make you into a systems thinker or a systems practitioner. It can only provide you with a framework through which you can develop your own characteristic ways of being a systems thinker and a systems practitioner.

You may already have encountered in previous Systems courses some of the central ideas of systems thinking.

Gather up your ideas of what these central ideas are by spending around 15 minutes on the following activity.

Activity 5

Make notes on what you think are the main features of systems thinking.

This is not a test question. There are no right or wrong answers. I am simply inviting you to explore what you already understand about systems thinking. Try to make your answer as comprehensive as you can. You could use diagrams if they're a more convenient way for you to represent your ideas.

If you have already studied Systems, you may find this task quite demanding because you will have to abstract these general ideas from what may be quite detailed understandings. Don't be afraid to spend slightly longer on this if you need to.

If your only experience of Systems is through any background reading you may have done, you may want to base your answers directly on your recent reading. That's fine but try to ensure that, in doing this activity, you are building your understanding and not just abstracting a list from someone else's ideas.

As before, date your notes and leave room for later additions. Put your notes with the rest of your Learning Journal.

Your notes from this activity will form a powerful basis from which to build your understanding of, and capacity for, systems thinking. You will develop your own ways of working with the notes you take as you work through the unit. My own way is to add new material in a different colour, indicating the date of the new colour. When making paper-based notes I've also sometimes photocopied the notes and added new notes to the photocopy, which I photocopy again for yet more amendments and crossings out, dating each one as I go. This saves completely re-writing and I only need to rewrite when I have a different appreciation of something, or when it has developed so far the old version is no longer helpful as a foundation. Other people use computer files in a similar way. I prefer not to throw away any old version, even if it gets superseded. It provides me with a record of my developing understanding, especially if I note down what I now understand and why I now think the old understanding is unhelpful. Even notes I think are redundant can prove to be the anchors for new insights.

You don't have to do it my way but I would urge you to find a way that suits you. You will need to be able to record your own learning. Perhaps even more importantly, you will find these notes invaluable as you take responsibility for your own learning.

My own answer to Activity 5 follows. You should not treat this as the right answer. You should certainly not make judgements about your own performance in the light of my response. My notes arise from my experiences, yours arise from your own. I would like to think you and I were both engaged in an activity that gives rise to new experiences and thus builds our own understandings from our own experiences. So I would much rather you treated the following as if we were in a conversation and use my ideas to develop your own.

The important features of systems thinking, as I see them, are these.

Systems thinking respects complexity, it doesn't pretend it's not there. This means, among other things, I accept that sometimes my understanding is incomplete. It means when I experience a situation or an issue as complex, I don't always know what's included in the issue and what's not. It means I have to accept my view is partial and provisional and other people will have a different view. It means I resist the temptation to try and simplify the issue by breaking it down. It also means I have to accept there is more than one way of understanding the complexity.

Complexity can be quite scary. But it need not be: complexity becomes frightening when I assume I ought to be able to ‘solve’ it. Systems thinking allows me to let go of this notion and allows me to use a multiplicity of interpretations and models to form views and ideas about the complexity, how to comprehend it, and how to act purposefully within it.

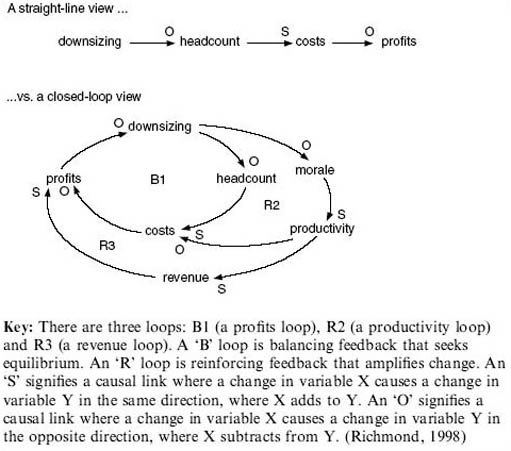

Systems thinking attends to the connections between things, events and ideas. It gives them equal status with the things, events and ideas themselves. So, systems thinking is fundamentally about relationship and process. It is often the relationships between things, events and ideas that give them their meaning. Patterns become important. The nature of the relationships between a given set of elements may be manifold. They may be causal (A causes, leads to, or contributes to, B); influential (X influences Y and Z); temporal (P follows Q); or relate to embeddedness (M is part of N). These relationships spring to mind immediately but there are many others, of course.

This attention to relationships between things, events and ideas means I can observe patterns of connection that give rise to larger wholes. This gives rise to emergence. Thinking systemically about these connections includes being open to recognising that the patterns of connection are more often web-like than linear chains of connection.

Systems thinking makes complexity manageable by taking a broader perspective. When I was studying engineering as an undergraduate, we were taught to break down problems into their component parts. This approach is so deeply entrenched in western culture it seems natural and obvious to anyone brought up or educated in this culture that this is the way to tackle complex problems.

While this approach is powerful for some problems, it's hopeless for others. For example, it now seems clear that climate change induced by human activity is likely to have major impacts on the planet, its environments, and its living organisms, including people. But all of these effects are so interdependent it is impossible to discover what the effects are likely to be by breaking the problem down.

Systems thinking characteristically moves one's focus in the opposite direction, working towards understanding the big picture – the context – as a way of making complexity understandable. Most people recognise they have been in situations where they ‘can't see the wood for the trees’. Systems thinking is precisely about changing the focus of attention to the wood, so that you can see the trees in their context.

Understanding the woodland gives new and powerful insights about the trees. Such insights are completely inaccessible if one concentrates on the individual trees. Figure 3 illustrates this sort of shift of attention vividly.

Systems thinking seems to come more naturally to some people than to others. Others have to learn to think systemically. People trying systems thinking for the first time find it quite tricky in the early stages. The temptation to break down the situation of interest into smaller bits is strong. The systems approaches you will encounter take account of this and are designed to enable you to capture the complexity before you move on to exploring it.

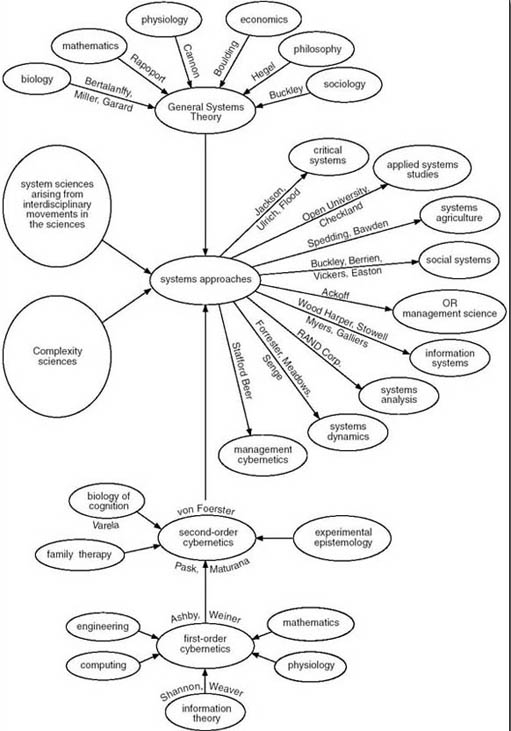

During the 1980s and 1990s, there were significant advances in Systems theory. There were two main drivers for this. One was the tremendous advance in computing capability. This allowed the behaviour of fluid, chemical, biological, and other phenomena to be modelled through time. This generated wonderful new insights into what came to be identified as chaotic phenomena. The second was the renewed synergy between biology and Systems. Both these stories are exciting, and there are a number of well-written books for the general reader that describe some of this work (Would‑be Worlds (Casti, 1997, John Wiley & Sons Inc., New York) arose out of the computer exploration of systems behaviour. James Gleick's classic Chaos (1987, Penguin, London) is also in this tradition. Fritjof Capra's The Web of Life (1996, Harper Collins, London) explores some of the developments in biology that arise from a systems perspective).

Regarding the second driver, the synergy first emerged in the early 20th century among biologists concerned with the properties of whole organisms. This led to an exciting phase of synthesis of ideas from many disciplines that gave rise to General Systems Theory. Since that time, biologists who look at living systems as a whole have turned to systems theory for new insights and, in response to their findings, systems theorists drew new insights from biology.

For me, the practicality of Systems is even more exciting than these developments. This unit is as much about systems practice as it is about systems thinking. There is an exciting synergy between systems theory and attempts to find better ways of engaging with problems and opportunities.

This is what this unit is about. It is an invitation to engage with systems thinking in such a way that you are better able to address the problems, complexities and opportunities that you encounter as you engage with the nitty gritty of whatever you do. Systems thinking provides me with tools-for-thought and the opportunity for a powerful way of looking at the world, whatever the context. The contexts stretch all the way from international issues such as global warming to the day-to-day problems that arise in work, in domestic life and in the local community.

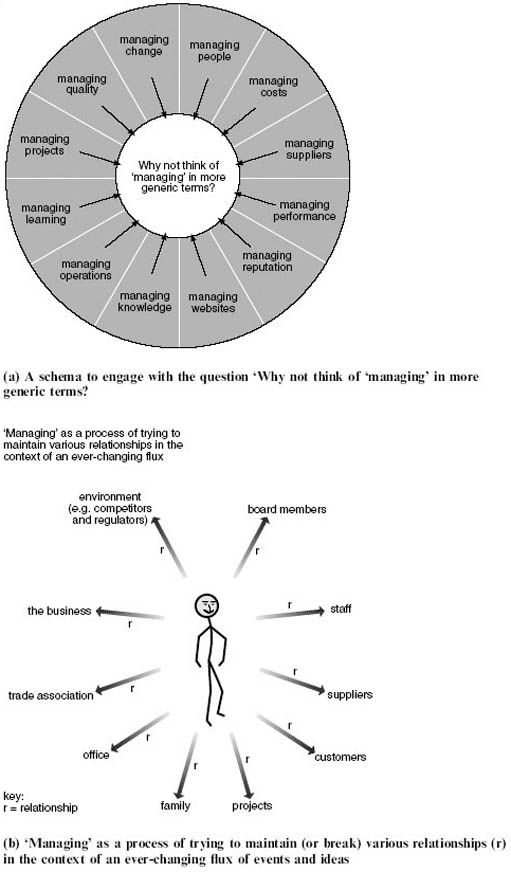

Systems practice in the context of this unit refers to the practice of Systems within whatever profession or calling you follow. You can be a systemic medical practitioner, a systemic wood turner, a systemic technician or a systemic manager by applying systems thinking, insights and approaches to the complexity that you encounter in any of these or other domains.

2.3 Taking responsibility for your own learning

Not much of this unit conforms to the traditional pattern I mentioned earlier – the theory-example-exercise pattern. In particular, you will find you are expected to discover much of it for yourself. Why is this? This is a legitimate question and deserves a full answer. One year, a student at a residential summer school complained I had not taught him properly. I was, he told me, an expert and so why did I not demonstrate how to tackle the problem he was working on and pass my expertise on to him. He felt the tutorial was ‘a wasted opportunity’. I could understand why he felt aggrieved. But I think he had missed an important feature of learning a skill such as systems thinking.

More and more, I've come to realise that whatever expertise I may have in systems thinking and practice, it is my expertise and it only works for me. In this I find myself in agreement with C.W. Churchman (Churchman (1971) The Design of Inquiring Systems, Basic Books, New York), who was one of the first people to write about what systems thinking might mean in practice, when he said ‘there are no experts in a systems approach’. When I look at the people whom I believe to be experts in this area, I realise there are many ways of being good at systems thinking and many ways of being good at systems practice. Each systems thinker seems to be good in their own way. I believe this is because Systems is about ways of experiencing the world, ways of thinking, and about ways of dealing with the complex situations I encounter.

Consequently, systems expertise is unique to each person. I cannot tell you how it's going to work for you or how you should understand it. You have to find your own ways. All I can do is to invite you into experiences that are likely to help you create your own meanings from the material. As well as being the only logically consistent way of learning systems thinking, there is plenty of research evidence (for example, see Using Experience for Learning (Boud, D. Cohen, R. and Walker, D. (eds) 1993, Open University Press, Buckingham)) to show that understandings and knowledge that one acquires through discovery is retained and developed much more readily than the understandings one acquires through being told, or even shown.

Taking responsibility for your own learning in this way is challenging but it need not be difficult. It requires a preparedness to experiment with ideas and styles of learning that may not initially feel right or comfortable.

All this means learning Systems is an intensely personal business. Don't worry if you're not used to reflective learning, you will be able to develop your capacities for learning this way, as you go. This is why it was important to think through what you want to achieve from the unit. It can operate at a level beyond acquisition of skills and knowledge. Because it is about different styles of thinking, the process of thinking systemically can itself give rise to new forms of learning. It has the capability of bringing understanding into being from sources inside oneself. This is the process known as reflective learning.

For some people, systems thinking will be something they practice from time to time. It will be a set of tools-for-thought they use when the need arises. This is a powerful and important potential outcome from the unit. The unit can also lead you towards becoming systemic, as well as being about systems. You can use it to become a different sort of thinker.

Either way, I strongly urge you to tackle the activities. They are designed to enable you to discover your own learning by experience. They are much more important than practice-makes-perfect activities. They will support you in making systems thinking and systems practice your own. Without them, systems thinking and systems practice remain ‘out there’ – something you may know about (description) but not know how to use (competence). This unit has aspirations beyond that, which I hope you will come to share; to support you in becoming a systems thinker and a systems practitioner. This is why the activities so far appear to be focused on you. You might see them in terms of preparing the soil in which skills, competencies and confidence can grow.

2.4 Appreciating epistemological issues

Common sense tells me my experience and understanding of the world are limited. I am 173 cm in height. That limits my view of the world. It may not matter much that I cannot see what my house looks like from above but it does mean there will be things going on in the roof I may not notice until they impinge on areas that I can experience.

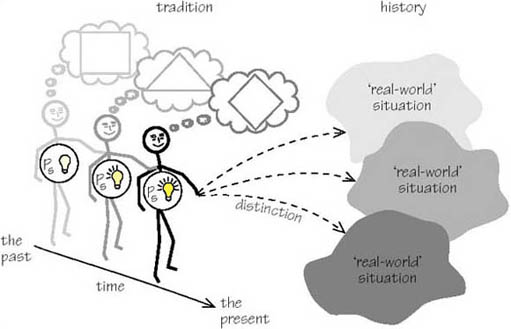

More significantly, there is a real limitation on understanding the experiences of other people. You might tell me about your experience but your description is likely to be only a partial representation and, however good your description, I cannot share your experience. I can only construct my own mental representation of what your experience might be like. But the limitations on my understanding of the world are even more fundamental than this.

My mental image of the world is a model. It is a partial representation of reality based on the partial knowledge I have of the external world. So, when I think I am thinking about the world I am thinking about my model of the world. This model of the world is built up in a way that is itself a model. So I am using a model, built by a model, to represent the world I think I see.

This has important implications. The model that represents the world tells me what I see and tells me what to see. The model both limits what I see and reinforces itself. When I think about the world, I am thinking about my own thinking; I have no direct access to the world at all.

Many people find this idea unsettling when they first meet it. It seems to defy common sense. It raises the question of how real the so-called real world really is.

Many people think of the brain as very similar to a computer. Both have a similarly large proportion of ‘processors’ operating on internally generated signals. But there is an important and absolutely fundamental difference. The computer does not create its own meanings. The computer has no capacity for deciding, for example, which are its favourite paintings in the National Gallery. I do. I have a history of interacting with external stimuli that generate new ways of interacting with further stimuli and the internal structure of my brain changes as a result. The computer's ways of dealing with data are not the result of its own self-production. The way the computer works remains the same, whether it is processing pictures from the National Gallery or whether it is processing letters of the alphabet. The rules that relate input to output are constant over time.

The question of what I can know about the outside world is an ancient one and has always been central in philosophy under the theme of epistemology. Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that deals with knowledge and knowing: how do I know about the outside world? how do I know my senses are not fooling me? what constitutes evidence about the world?

Neither discussions about modelling, nor the insights of philosophy, can tell me how true my internal representations of the world are, but neurological studies seem to suggest the outside world is unknowable as it is. This unit considers this important issue. Epistemology becomes a central concern. This contrasts sharply with many other courses where epistemology is never addressed. The world is assumed to be ‘out there’ and more-or-less as it appears.

Recognising the world is unknowable as it is presents me with a choice. How do I deal with the day-to-day observations and events that seem to emerge from it? Each person, once they become aware of this unknowability, is confronted with, and needs to make their own choice.

Each choice is individual but seems to cluster around three main poles. The first of these is to adopt a stance that the world is more-or-less as I see it, and to ignore the incompleteness of my viewpoints and my representations. This is equivalent to saying ‘there is no epistemological problem about the world as I see it’. The second is to decide that the world is more-or-less as I see it but to recognise that my viewpoint is limited and the view-from-here may be misleading because it is only partial – there is no view of the roof, to use my previous metaphor. This is a stance that accepts that I must be careful to explore the world as fully as I can because I cannot see everything and may be misled. The third pole is to take on fully the implications of the world's unknowability. This stance demands that I always carry an awareness that I will never know the world and must therefore always be trying to account for my own role in my perceptions of the world. Consciously making the choice between these poles, and all the variants between, is an act of epistemological awareness.

Later in the unit this theme will be explored more fully – the choice one makes has profound implications for one's ranges of thought and action. Of course, knowing most of what I'm aware of is actually generated within my own brain does not mean I can make up any version of reality I choose. But it does mean I have to recognise my knowledge of, and understanding of, the world is partial and provisional and depends to a significant extent on my internal processes of constructing representations. This theme will come up repeatedly but for now it seems to suggest a number of attitudes or mental stances will be helpful.

Some of the mental attitudes I try to adopt are:

Being open and sensitive to all kinds of information about a situation: not just so-called factual information but impressions, intuitions and hunches, including other people's when they express them;

Being willing and able to see the situation from all kinds of points of view in addition to my own;

Being as open as I can be to seeing the situation and not letting my theories, presuppositions and assumptions tell me how I ought to see it;

Not taking terms of reference, boundaries or constraints too seriously; I try to assume they may not be as rigid as they seem to be;

Trying to find out how other people see the constraints and boundaries;

Being wary of any solution to a complex question (including my own solutions);

Enjoying diversity and complexity in a situation; resisting the temptation to discard inconvenient bits of information; paying more, rather than less, attention to awkward facts, impressions or ideas;

Not minding too much if there are areas of uncertainty in my understanding, or bits of information I don't have; being sceptical about the facts I do have.

Adopting a set of stances isn't necessarily easy so here are some suggestions about things you can actually do when you are looking at a complex situation that mystifies you in some way. (There are likely to be times when the unit itself looks like a complex situation that mystifies you.) Practising these will help you to develop the open, enquiring style that can make systems work so exciting.

Make sure you include in your thinking about the situation:

The preceding history and the wider context of the situation;

Information about how people (including you) involved in the situation feel about it; what are the hunches, intuitions and suspicions they, and you, have about it;

Information about the dynamics (procedures, flows, communications, feelings) of the situation as well as the structure (roles, organisation framework, boundaries, materials, components) and how the process and structure fit together;

Information about how the situation appears to other people, including those around the situation as well as those directly involved;

Attention to what is not going on and what is not present.

2.5 Review

The title of this unit could have been Juggling with complexity: searching for system. This title seemed to capture something essential about the unit. Juggling is a rich metaphor and will be used explicitly in Part 3. But it also carries the idea of a skill that needs to be practised and that might seem incredibly awkward to begin with. You may find this idea helpful as you review your work in Part 1. Juggling is also a skill that, once practised, becomes second nature. This too may be an important idea to carry forward to Part 2 as you begin to work on the search for system.

In working through this section, you have identified some of your initial expectations and I have explained some of what I think you will discover as you work through the unit. It would be appropriate at this point to look at some of the questions I asked you about your expectations again and note ways your expectations have changed.

Spend a total of around 30 minutes on the next three activities.

Activity 6

Looking through your previous notes and my previous questions, identify and record any ways your expectations have changed.

Have any new expectations emerged from your reading of this new section? Do any of your expectations look less realistic now? Do your previous expectations seem more, or less, likely to be met.

Do you have any new ideas about what you would like to get from the unit?

Activity 7

Do you feel able to adopt any of the attitudes I have suggested?

Most people move into and out of the attitudes I described earlier. The difference I am proposing is that you consciously try and adopt them as you improve your capacities as a systems thinker. Do you think these attitudes will be useful to you? Have you adopted them in doing this activity? How successfully? You may like to record some judgement about whether you like the idea of these attitudes. Notice that I referred previously to ‘a willingness to experiment with styles of learning that may not initially feel right or comfortable’. Does this reflect anything you are experiencing at this stage?

Activity 8

How do you understand the focus on your own responses in the activities and in the reading you have done so far?

Notice your intuitive responses as well as your intellectual responses. Are you puzzled? Stimulated? Surprised? Excited? Hoping it will get somewhere? Eager to find out more? Suspending judgement? Frustrated?

Any or all of these responses, even if they are a little difficult to live with, are likely to enable you to make good use of what comes in the rest of this unit.

It may also be you are unused to, or uncomfortable with, the focus on yourself and your own experience in an academic course of study. This need not inhibit your learning, provided you recognise your discomfort. If you stick with it, the unfamiliarity of this type of approach is likely to disappear. The payoff: you can become a person who can think and practice systemically. Without engagement with your self, Systems is likely to remain, for you, a collection of techniques that are never really your own.

It would be unreasonable for me to expect that you would instantly recognise this is an effective way of starting studying Systems.

Make a note of your present understandings and responses.

Given up already?

Figure 3 can be seen as a Dalmation (spotty) dog. The dog is facing away from the viewer, sniffing the ground with its black ear falling forward. Its head and dark collar are half way up the picure and about one third of the way across the frame. Its rump is near the right hand edge of the frame.

Part 2 Experiencing complexity

Part 2: 1 Introduction

I have a number of purposes in mind as I write Part 2. You can read these in conjunction with Figure 4.

Firstly, I want to give you the opportunity to get on with it – actually getting stuck into an experience of a complex situation. Through that experience, I want to exemplify the process of getting to grips with the complexity of the situation by looking for systems, or elements of systems, within it. I want you then to have the opportunity to use these systems to understand the situation.

My second purpose is to allow you to draw together some of your previous understandings of Systems with some of your systems skills and to consolidate them. They will then form a firm foundation for proceeding with the unit. In particular, since diagrams will be really important throughout the course, I want you to have an opportunity to practice and develop your diagramming skills.

Make good use of OpenLearn unit T552_1 Systems diagramming. This unit will explain the theory and ‘rules’ for each diagram type and how each diagram type is constructed and refined.

If you have previously studied a Systems course, Part 2 will function as a kind of work-out, allowing you to ‘get fit’ with a new coach in a new gym. You will need to develop systems-diagramming skills for the first time. You should pay particular attention to understanding the purposes and conventions of each diagram type, as described in T552_1 Systems diagramming. Whether or not you have done systems diagrams before, T552_1 is an important resource in working through this part. You will need to refer to it later in your work on this case study.

My third purpose is to support you in acquiring the skills of assessing the quality of your own diagrams. The case study you will be engaging with is very complex and it would be possible to draw an enormous range of diagrams of each type, each highlighting different features of the situation and each taking a slightly different perspective. This means that, if you are truly to engage with the complexity, you are unlikely to produce a diagram similar to any of mine. How are you to know if your diagram is any good? The answer is first to recognise there are many ways a diagram can be good. The second is to develop a series of questions, or several ways of looking at your own diagram, which will prompt you to improve your diagram if it needs it.

As you work through the diagramming activities later in this part of the unit, I suggest you make a point of noting the criteria I suggest for evaluating your diagram in your Learning Journal. They will come in useful as you do further diagrams. Being able to evaluate your own diagrams is likely to be a hugely more effective way of developing your skills than comparing your diagram with mine – especially when mine is unlikely to be addressing the same issues as yours.

My fourth purpose is to convey something of the flavour of the unit. At the end of Part 2 you will probably have formed your own sense of what flavour has been conveyed. For me, this flavour has to do with the way a complex situation can be understood by interacting with it in a number of different ways, taking different viewpoints or perspectives.

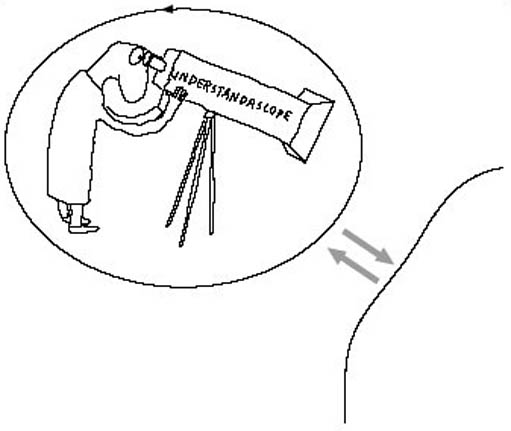

It is as if, with a telescope, I observe the situation from a number of different vantage points. This will reveal images of the situation from different directions so that different parts and sides become apparent. But I also take the trouble to view it at a number of different magnifications, including more or less of the situation and its environment in each image. I might also change the focus, examining both foreground and background. Later in the unit, the telescope itself (if I extend the metaphor) is examined to discover what it is good at showing and what it tends not to see so well.

6 Part 2: 2 Immersing yourself in complexity

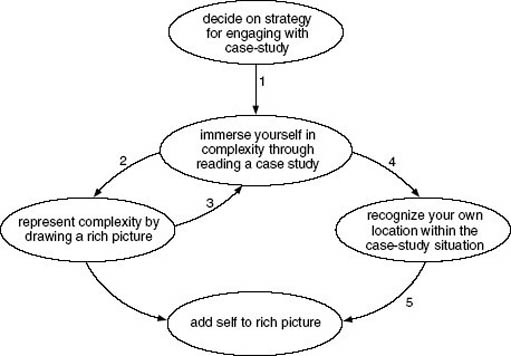

The first three activities in Figure 4 are to plan a strategy, then to immerse yourself in an example of complexity, and then represent that complexity through drawing a rich picture. I've selected a rich picture as the focus of this task because it is a means of bringing you into a rich encounter with the complexity of the situation described. The rich picture is a representation of your encounter with the situation, and so drawing a complete rich picture needs you to have represented the situation to yourself. The rich picture allows you to see the whole situation at once – something that would be very difficult to do in your head. My purpose is to offer the encounter, and then to consider the experience of the encounter, between you and the complexity. The rich picture is simply the means and the evidence of this happening. Bear this in mind as you work through the sequence of activities represented by Figure 5. Figure 5 is an unfolding of the first two activities of the overall task of experiencing complexity described by Figure 4.

At this point, I would like you to prepare for reading the case study, the second activity in Figure 5. Your task is simply to grasp as much of the case-study complexity as you can. Notice that, at this stage I am not suggesting you do any analysis of the situation described. At the end of this task you should only aim to have a general impression of the overall complexity and a representation of that complexity. Detailed study and analysis will come later. The case study is about 9500 words long. The next activity should help you decide how to tackle this reading.

There are a number of things in planning how to deal with this amount of material. Firstly, you may not be able to grasp all the detail at the first reading. Don't worry about this. The case study was chosen, in part, because the feeling of being overwhelmed is quite a common one in systems practice and the I thought this would give you some of that experience. Even if you feel overwhelmed, don't be discouraged. The later activities are proven ways of dispelling the sense of being overwhelmed. A bit of determination to get through it all will help.

Spend about five minutes on this activity.

Activity 9

How do you read most effectively?

It may be helpful to think of a specific experience where you were trying to understand a detailed piece of text. Did you have a strategy for reading it? What was that strategy? Does your strategy involve skim reading first to get an overall sense of the shape and returning to the beginning for a more careful read and then, finally, a third pass taking notes about the development of the narrative? Or perhaps your strategy, completely different from the first, involves a process of careful reading taking notes, followed by a second read-through to check the notes are as complete as they can be. Be as specific as you can in identifying a strategy that works for you. Make a list of the sequence of processes you anticipate will work well for you.

You should also assemble materials for drawing a rich picture.

Once you have identified a style of text-reading you think will work well for you, move on to the task of reading the case study. The case study was chosen because it is a real-life example of a complex situation where an attempt to put right a problem had results nobody intended. It also contains lots of soft complexity. So-called soft complexity is often the hardest to deal with since it involves human values, beliefs and emotions. In this case study, all of these collide.

Expect to take a total of around 5 hours to complete the next activity but if this unit is your first serious engagement with systems work, allow rather longer. You will need to get to grips with the concept of diagramming and, the concept of drawing rich pictures in particular. Don't attempt to tackle the task in one long session. You may get more out of it if you take it in two blocks of time, perhaps on consecutive evenings.

Activity 10

Read the case study ‘Financial support for the children of lone parents’ by Joyce Fortune (attached below) and draw a rich picture. (You can find some extra guidance on how to create a rich picture at this link.)

Using your chosen style of reading, read through the case study and represent the situation in a rich picture. Make sure your rich picture is as rich as you can make it. Remember a rich picture is not intended to be an analysis. If you have any thoughts and ideas about the situation, or your rich picture of it, make a note of them so you won't forget but concentrate on the main task of representing as much of the situation as you can in the rich picture.

Click on the link below to read Appendix B.

7 Part 2: 3 Representing your experience of complexity

7.1 Introduction

The last activity was a demanding task. People I asked to do it during the writing of this unit, found it took a lot of concentration but it brought up lots of ideas, feelings and suggestions for action. Most of them were also concerned their rich picture might not be good enough. I imagine you will share some of these reactions. If you share any of these concerns, remember there are lots of ways of drawing a good rich picture and almost all rich pictures can be improved. Improving your rich picture, and your appreciation of the complex situation it represents, is the next task.

Activity 11

Review your rich picture.

When you come back after a break, spend about 5 minutes taking a good look at the rich picture. Is it as complete as you thought it was? Are you pleased with it? Are you stuck for ideas about how to improve it? Do new features strike you as you look at it? Do questions arise about it, or the complex situation it represents?

Make appropriate additions to the picture if necessary and record any thoughts or questions that occur to you in you Learning Journal.

Taking a break seems to be an important part of the process of drawing a rich picture. It is almost as if one of the characteristics of the process is to generate thoughts and ideas that only become apparent when you see it afresh.

You have now completed the fourth activity in the central spine of Figure 5.

7.2 Complexity and rich pictures

This section is mostly concerned with thinking about your rich picture and the complex situation it depicts.

There are lots of ways of drawing a good rich picture and very few ways of drawing bad rich pictures. So my next strategy in supporting your learning, and your experience of this complex situation, is to propose a number of checks you might use to ensure you have not fallen into the trap of the less-effective rich picture.

Although my discussion will focus on rich pictures, I am also talking about the complexity the rich picture represents. I am using the task of generating a useful rich picture to illustrate the process of experiencing and capturing complexity.

7.2.1 Trap 1: representing the problem and not the situation

This trap is one of the most fundamental mistakes you can make in systems thinking. There are lots of metaphorical phrases in English that can entice you into the trap. We can talk about ‘the nub of the problem’, ‘the key issue’, ‘the basic problem’, ‘the real difficulty’ and so on.

Like all traps, once it has sprung, it can be very difficult to get out. The trap seriously limits one's ability to think about the situation in its full complexity. This is precisely because, by identifying every problematic feature as stemming from one single interpretation of the problem, you limit your possible ways of dealing with the situation to those that might be answers to this single problem. You have imposed simplicity on the situation, which does not reflect the very complexity that makes it problematic.

In contrast, one of the reasons this case study seems to be complex is precisely the difficulty of identifying anything that could be described as the key issue. It seems to be a tangle of interrelated key issues.

The whole point of a rich picture is to represent all you can about the situation. To identify the problem within the picture, or to include only the elements that seem problematic, is to prune out potentially important elements of the complexity.

So, the check for avoiding this trap is to ask:

Does this rich picture represent the situation or is it just my interpretation of what the problem is? Does it include all the features noted as problematic?

7.2.2 Trap 2: the impoverished rich picture

A distinguishing feature of rich pictures that turn out to be useful seems to be they are just what they say they are, rich. If I take usefulness as the criterion, the useful rich pictures are the ones bursting with interest and activity. They don't seem to tell a single story, there are lots of stories going on simultaneously. They reveal stories you didn't consciously build into them.

How is such a rich picture to be achieved?

Use everything you find in the situation. This means incorporate everything you know about the situation. Either put things into the picture as you re-read the description; or make lists of the protagonists, the organisations, the structures, and then put them into the picture. Include people as well as the roles they inhabit.

Indicate the connections. Where the structural entities you listed above have connections and relationships between them, indicate what they are. There are all sorts of ways of doing this, especially if you ask yourself about the nature of the connection. You could use physical proximity (or distance) or representations of the nature of the connection (hearts, daggers drawn, telephones, deafness, walls of silence). Lots of people quite unconsciously use visual metaphors in their everyday language. (‘Every so often they drop a bombshell on this department.’ ‘We're swamped with memos.’ ‘We're drowning in paperwork.’) Talk to yourself about the situation and you may pick up clues about how to represent features of the situation. Arrows and lines tend to be less useful but they're not forbidden. Don't force the images, use the ones that seem to come naturally. There is no library of approved symbols.

Use all the geographical locations, if this is relevant.

Use all the processes. Include all the changes, and activities. Include impressions as well as reported facts.

Some people use computer clip-art to draw rich pictures. It rarely works in my view. Some essential quality seems to be missing. This quality might be ownership or engagement or it may be the very act of sitting at a computer keeps the activity at a rational level – it does not allow for the impressions and half-formed awareness to express themselves through the act of making marks directly on to paper.

The check for avoiding the impoverishment trap is to ask:

Have I included everything I know about the situation in my representation of it?

7.2.3 Trap 3: interpretation, structure, and analysis

If you deliberately impose an interpretation or analysis on your picture, you preclude the possibility of seeing other, potentially more interesting, features later. Remember the rich picture is a representation of the complexity. If you structure that complexity, you are no longer representing it as you experience it. You also lose the possibility of using the drawing process itself as a means of encountering the complexity in all its fullness.

The trap takes a number of forms. Beware of representing events in their chronological sequence, either explicitly or implicitly. Also, organisational structure may take over and become the structure of the whole picture. Elements of other diagram forms may creep in. (Systems maps and influence diagrams can be quite a temptation.) Watch out for the temptations you are susceptible to. Artistic abilities, if you have them, can represent their own temptations – they too can be a part of the structuring trap.

It may be inevitable that interpretations suggest themselves as you draw. Stop yourself thinking ‘this is really about …’ One way of stopping this is to jot the idea down somewhere – not on your picture – in the form of a question. Once you've written it down, the idea is much less likely to keep popping up as if it were trying to ensure you won't forget it.

So, the check for avoiding this trap is to ask:

Is this rich picture telling just one story or is it rich enough to suggest lots of stories about what's going on?

7.2.4 Trap 4: words and wordiness

I have seen some effective rich pictures with lots of words in them but they are quite rare in my experience. More often, lots of words make the rich picture less rich. Part of the later use of a rich picture might include looking for patterns. Words inhibit your ability to spot patterns.

If you do use speech bubbles, use what people say, not your interpretation, unless the bubble is about some general attitude. Examples might be ‘Aaagh!’, ‘Help!’, ‘Oops!’ – the sort of things found in comic books.

The check for avoiding this trap is to ask:

Do I have to do a lot of reading to see the relationships between elements in the picture?

7.2.5 Trap 5: the final version trap

Ironically, the biggest mistake you can make, having got this far, is to assume your picture is finished. New realisations will crop up. Add these to your picture as you appreciate more and more of the complexity.

So, the check for avoiding this trap is to ask:

Have I had any new insights about the complex situation since I last added something to this picture?

SAQ 1

List the main traps you can fall into when you draw a rich picture of a complex situation.

Examine the rich picture you have just drawn and identify any remaining traps in which your picture may be still be caught.

Answer

The main traps you can fall into are:

representing the problem, or your interpretation of the problem, and not the situation;

the impoverished picture trap – not including everything that seems important to, or related to, the situation;

including your own analyses, interpretations and structuring in the rich picture;

too many words; they can obscure or diminish the richness of the picture;

assuming the rich picture is the final version.

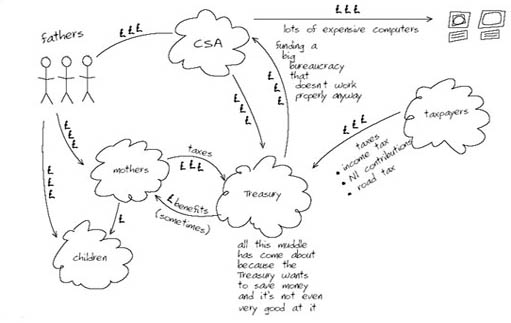

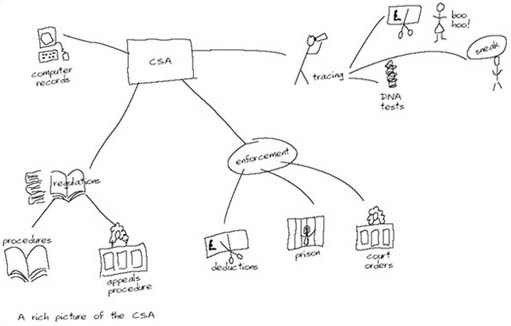

The rich pictures that follow give an indication of some common traps.

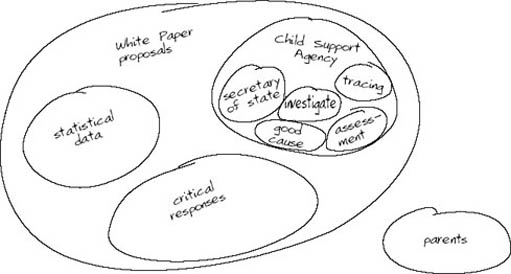

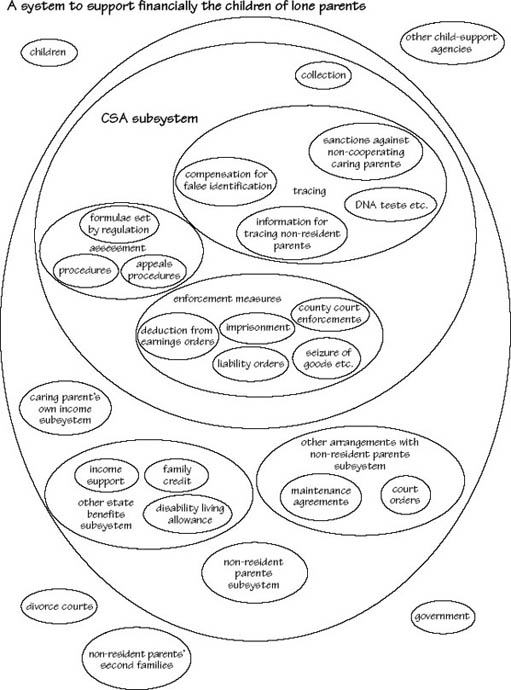

Figure 6 seems to me to fall into several traps. It is certainly impoverished; there are a lot more things that could, and should, have been drawn. In part, this impoverishment is due to the fact that the drawer has chosen to structure the picture in terms of money moving about, so anything that cannot be represented that way has been left out. The rich picture almost looks like a flow diagram for money. The picture also contains some rather superficial analyses by making judgements. The drawer might also have been alerted to this trap by the words that appear; there are quite a lot of them for such a simple picture.

This picture has also broken one of the rich-picture rules; it should have a title. Also, it does not include the drawer.

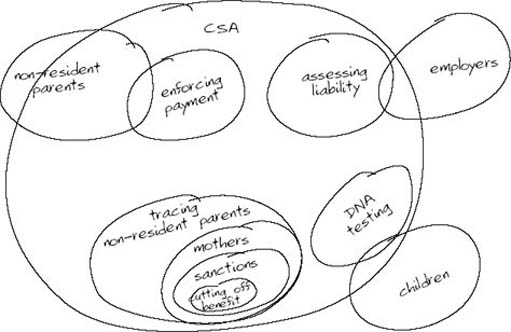

Figure 7 also seems to be rather impoverished. Lots of the situation is missing. The picture also seems to be an organisational chart of sorts. The lines seem to suggest it's a disguised representation of the activities of the CSA. Of course, those activities do need to be included, but to include the lines is an element of structuring that will get in the way of the eventual usefulness of the picture. The picture also suggests, by its central position and the spokes coming out of it, the CSA is somehow the problem, an interpretation that should not be there. The drawer might have spotted this trap as they gave the picture its title. The picture should be about the situation, not just components of it.

Like Figure 6, the drawer has forgotten to include themselves in the picture.

7.3 Getting out of traps

Remember to date your rich picture and not to throw away any previous versions. Old versions of rich pictures provide you with a record of your developing understanding.

The next activity is an invitation to improve your rich picture by digging yourself out of any of the traps you may have fallen into. In this activity, I suggest a certain ruthlessness in reviewing your efforts so far. You should not, however, see this as an evaluation of your performance in the task. My experience is that knowing about the traps is only part of the skill of representing complexity. Sometimes one simply falls into them.

The worst possible result is falling into a trap and not realising it has happened. So, the next bit is about learning to recognise the traps when you've fallen into them and learning to get out of them. With that experience behind you, falling into any of the traps isn't a disaster. My hope, without being malicious, is you've fallen into at least one trap and in the next activity you'll get out of it. The next activity may take only 15 minutes. If you need to re-draw it will take longer – but not as long as the first drawing took.

Activity 12

Look at your rich picture.

Check you have not fallen into the trap of an over hasty identification of the problem. It is not easy to spot this trap if you have already fallen into it, so be ruthless. Be prepared to re-draw your picture if you discover yourself in this trap. It may be possible to add the necessary elements but the trap is such a disabling one that often it's better to completely re-think your representation. I've fallen into this trap, and still do, many times. In my experience, redrawing is never a waste of time.

Check you have not fallen into the trap of impoverishment. It's fairly easy to spot if your representation of the situation is rich or poor. Compare it with the example rich picture in T552. Has it got that same quality of buzzing with activity and interest? Use the tips for getting everything in described above. Make your picture as rich as you can.

Check you have not fallen into the trap of structuring, interpreting or analysing the situation. If you have, re-drawing may be worthwhile. Once structure, interpretation or analysis is there, it's hard to disguise them and they become a distraction.

Check the richness of your picture isn't swamped by words and the words are not structuring your representation of the situation. Make the necessary improvements. Add anything else that seems to be part of the situation.

You have now completed the activities connected by arrows 1 to 6 in Figure 5.

7.4 Complexity from someone else's perspective

You may already have noticed, and included, the author of the case study in your rich picture. The clues that this is necessary are in Figure 5 and in my comments about epistemology in the introduction to the unit. Just how important the writer of the case study is becomes obvious when you consider almost all the detail you have access to in this situation probably comes through that person's writing. Even if you have first hand experience, and are aware of all the intricacies of the situation described, it is the author of the case study who has largely defined the situation – an element of pre-structuring that needs to be recognised.

At this stage, it is not appropriate to try and evaluate just how much this person's view of the situation – whatever that view is – has influenced yours. But it undoubtedly has. Including the author in your picture is simply a recognition that, in writing the case study, she went through a process of deciding what was relevant; sorting what she would include and what she would leave out; she ordered it into a readable bit of text; and she made some judgements about when to use quotations and when to simply report. Just include the writer as an element of the picture, don't try and impose structure or i

7.5 Summary

I hope that, by now, you have a rich picture you are pleased with. This is a considerable achievement because, despite the informality of the rich picture's style, a rich picture that effectively captures the complex situation takes a lot of effort to achieve. It depends crucially on being prepared to enter into the experience of the situation of interest and to interrogate that experience thoroughly. Noticing is not enough. Each feature of the situation has to be carefully captured by representing it in the rich picture.

My point in inviting you to draw a rich picture was not just to give you practice in rich-picture drawing – useful as that will be for the unit. The drawing of the rich picture is also a means of enabling you to enter into relationship with this complex situation – to experience complexity.

This completes the first three activities in the activity sequence depicted in Figure 4 and the activities linked by arrows 1 to 8 in Figure 5. One essential element of the rich picture remains to be added, and for this, the focus of attention must be changed to experience another component of the complexity. This happens in the next section.

8 Part 2: 4 Being inside complexity

8.1 Loose ends

Before moving into a discussion of the missing element of the rich picture, I want to direct your attention to all the thoughts and ideas I have encouraged you not to put into your rich picture. I imagine you might have collected quite a list of loose ends. The next activity will involve some of these.

Expect to take about half an hour to do the next activity.

Activity 13

Identify and record any stake you hold in this situation in your Learning Journal.

First, identify any stake you hold in the situation described in the case study. Such a stakeholding might arise in any one of a number of ways.

Are you a lone parent, a parent who lives (or has lived) away from your children, or a parent with sole (or most) care of your children (or child)? Are you a child of a single-parent family? Do you have professional or other interests in the Child Support Agency; the Benefits Agency; or charitable or campaigning organisations working in these areas? Do you have a role in an equivalent agency outside the UK? Do you have any role in forming government or political policy? Do you subscribe, through membership or otherwise, to a political-party view on these issues? Do you have family members, friends, neighbours or colleagues, in any of these roles? Perhaps you have a stake as a tax-payer.

Record your current thinking about this situation.

In particular, record any ideas about what the core issues are, people or agencies that you might hold responsible for some of the problems described in the case study, areas where you feel clarity is missing, and so on. Are there places where you feel tempted to say things like, ‘if we could just deal with X then Y might be better’.

What passages of the case study seem to represent particular clarity or do you particularly identify with?

Make notes on your own view of the extent of parents’ rights and responsibilities with respect to their children, and the role the state should have, if any, in ensuring that children are adequately supported.

Record your current feelings about this situation.

Are you angry? cynical? amused? amazed? Do you have any feelings on behalf of any of the protagonists? Do you feel it's not fair? (Be specific about what's not fair, not fair to whom.) Do you have any positive emotions? Do you feel compassion (for whom?), empathy, approval (of what?), pleasure?

It's easy to censor feelings, especially perhaps in the rational activity of studying a unit. The censorship arises from the idea that irrational emotions have no place in rational discussions or from, for example, the desire to avoid passing judgement on someone else's behaviour or attitudes.

Feelings are not necessarily politically correct either. While political correctness can challenge us to examine the basis of our feelings, gut reactions are generally not guided by intellectual principles. Get past this censor as much as you can.

Another block to recognising feelings is the idea the feelings have to be justified in some way. You don't have to do this in this context. You should simply record the emotions that are there. Be as specific as you can about what you feel.

If you have no direct stake in the UK's arrangements for child support, perhaps because you live outside the UK, record your feelings and questions about the situation described. Include your impressions about the social arrangements that give rise to the situation described. Include also, any judgements you make about these. Does the text give rise to any questions concerning arrangements and social conditions in the country where you live?

If you pay taxes in the UK, or live in a household that pays taxes, what are your feelings about the situation as a tax-payer?

Record your initial views about what should be done to improve this situation.

Don't worry if these are based on gut reactions. Any ideas you have about what should be done, or about what you feel should be explored, should be recorded. They may be more or less feasible, or more or less long-term. Use the language that first springs to mind, even if it's in the form of, for example, ‘A and B need their heads banging together’, or even, ‘people should be stopped from having babies’.

In particular, if you have any ideas that take the form ‘X could …’, ‘X should …’, or ‘X ought to …’, record them because these word forms usually disguise some judgement about someone's culpability.

Some people find it quite easy to record their emotional responses to a situation – indeed, they might even find it quite difficult not to express their feelings forcibly. Others find it difficult to express, or even to recognise, any emotional response to a situation such as this. Other people are, of course, either somewhere between these two extremes or somewhere else altogether. Neither is good or bad. The point is, if I am to start thinking deeply about a complex situation I have to recognise I do have emotions, even if I'm not fully aware of them. They contribute to the complexity of the situation because they condition the way I perceive and evaluate the situation. Your own values are important. The point is not just simply to record your values and responses, and then ignore them, but to acknowledge them.

I and, I suspect, many other people, find it impossible not to have emotional responses to most situations. Indeed, without emotions I would not be interested in the situation at all. I would be less than fully human. The question then becomes, ‘How do I think sensibly about any complex situation I care even slightly about?’ The answer to this conundrum, I believe, lies in learning how to account for one's emotional responses as part of the complexity of the situation.

Professionalism, in Systems as in any other practice, assumes the practitioner will endeavour to set aside purely personal preferences in favour of attaining good resolutions in problematic situations. (Of course, a resolution has to be recognised as ‘good’ by somebody but that is another discussion and will come up later in the unit.) I'm not suggesting this professional standard be abandoned by systems practitioners. But, it seems to me unlikely anyone could be a good systems practitioner without having some views on, and opinions about the situation of interest.

So, as a systems practitioner, I need to be able to manage these views and opinions. This may involve setting them aside but at the very least it involves accounting for them. I can only manage what I know about and so, as a responsible practitioner, it seems to be important I acknowledge any prejudices so that I can take account of them. I can also be aware of the ways initial views, feelings and opinions condition what I am able to observe, what I am able to enquire about and what I am able to do.

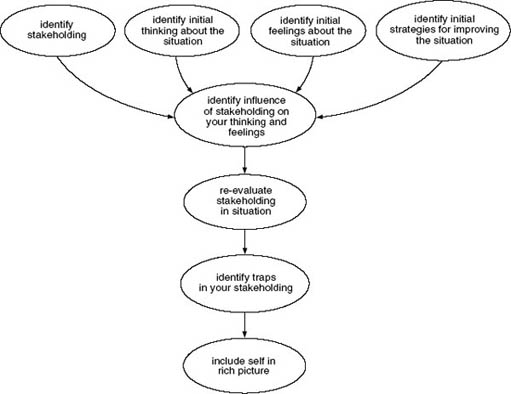

This theme will be taken up later in the course. For the moment, I want to propose the activities described in Figure 8 as a way of managing the complexity that you, as a person with experiences of, stakeholdings in, and feelings about the situation, bring to it. You have already completed the four activities at the top of the diagram.

The next activity addresses the role your stake in the situation has in supporting some of your initial reactions to the situation, including your emotional ones.

Expect to take around 10 minutes on this activity.

Activity 14

Examine the initial responses you identified in the light of the stakeholding you identified earlier in Activity 13.

Are they related in any way?

Even if you did not identify a specific stakeholding, do your initial responses form any pattern? Do they suggest you identify with any individual protagonists in the situation, or groups of protagonists? Do they suggest you have additional stakes, even if simply emotional ones, in the situation?

8.2 Stakeholder traps

I've found it's not at all uncommon to discover I have a stake in a situation. Complex situations often spread their tentacles into all sorts of areas, so that the number of people touched by them can be very large. This increases the chances of an individual acquiring a stake, even an indirect or second hand one. The human capacity to empathise draws me into a situation so that I form pre-judgements about fairness, blame and so on without really trying. In many ways this is to be welcomed – a direct stake can, for example, mean I have access to additional information.

But stakeholdings can also set traps. The principal one of these is the trap of getting caught in one perspective. If I am to be able to respond to a situation in a way that respects its complexity, I have to be able to see the situation from more than one point of view. Any view is always a view from somewhere. Staying with one viewpoint will mean some aspects of the situation will remain hidden. I have to move between viewpoints.

SAQ 2

Imagine some friends read the case study and they recorded their initial reactions as follows.

Jane: I've experienced exactly what this is all about. I've had no end of problems ever since Billy's father left. And the CSA has been no help at all.

Martha: Mmm! It doesn't really seem fair that fathers who've been very responsible and have met all the conditions of their court orders should suddenly find themselves having to pay out much more than they'd planned for.

Pete: This is all motivated by the government's drive to save money. It's fundamentally dishonest to dress it up as help for families.

Liam: I don't really have an opinion. If people chose to have children then their problems are all of their own making – and nothing to do with me. I just have to pay up through the tax system.

How would you help your friends to identify any traps to do with their first thoughts before they start to think more systemically about the situation? Hint: Whether your friends’ reactions are right or wrong, in your opinion, is not important.

Answer

Jane may be in the trap of thinking she knows all about it. She is certainly likely to know lots about it from the point of view of someone in her situation but this is not the same as knowing all about it. She may get trapped in her own perspective too. This perspective already seems to include the conclusion that the CSA is ‘no help at all’. She may need to make a conscious effort to include other perspectives as fully as possible and be open to seeing alternative views of the CSA.

Martha may need to make sure she is open to alternative opinions, even ones that could change her mind.

Pete seems to be identifying a single source for the problem. This is a trap. He is also making a judgement about a component in the situation, and that too makes him less open to seeing other perspectives on the problem. He may be right, he may be wrong, but moral judgements of this sort tend to obscure the multiplicity of motivations and issues that make up the situation.

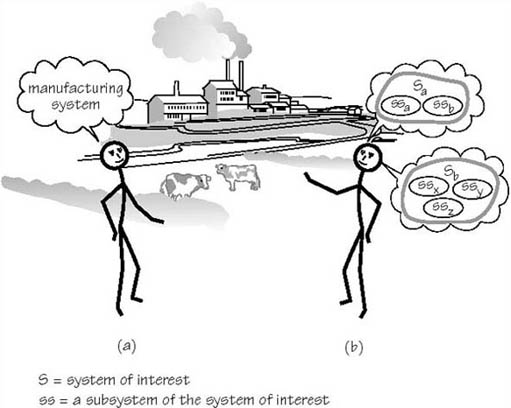

Liam does have an opinion. It seems to be a strong one too. He's also a stakeholder, through the tax system. He may find he gets stuck in the trap of feeling disengaged, by being engaged in what seems to be a ‘blame story’ that attributes the whole problem to parents. This is a pre-judgement that will get in the way of thinking clearly and systemically about the situation if he is not aware of it.