👉 Find out about The Open University's Geography courses. 👈

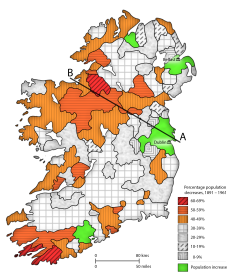

With regard to the future of rural Ireland, the issue is more nuanced than most of the headlines suggest. Not all rural areas are the same – their problems differ, so too do the solutions. This is demonstrated in the course materials which illustrate how uniqueness is constantly made and remade as different layers interact. This uniqueness is recognised by the Commission for the Economic Development of Rural Areas (CEDRA) report, which suggests that past policies tended to neglect it:

Neither rural areas nor the communities that live within particular types of rural area are homogenous. Past failures to adequately understand or fully appreciate the implications of this point accounts, to a large degree, for the increasing disparities between different types of rural areas.” CEDRA Energising Ireland’s Rural Economy, Report of the Commission for the Economic Development of Rural Areas, p. 36

Some rural places with highly engaged communities have been proactive in responding to the challenges confronting them through the development of their resources. The success of these groups, according to CEDRA, has been in the identification of a specific need, the identification of potential and subsequently harnessing a network of pre-existing supports. Their adoption of an integrated and territorial approach to the challenge of economic development is seen as key to their success. In many ways, this prescription echoes Father McDyer’s approach to the survival of the Glencolumbcille area over fifty years ago.

CEDRA’s recommendations argue for the need to facilitate local communities overcoming specific local challenges and exploiting local opportunities through the development of local resources (i.e. uniqueness) while linking with local authority and regional authority economic strategies (i.e. interdependence).

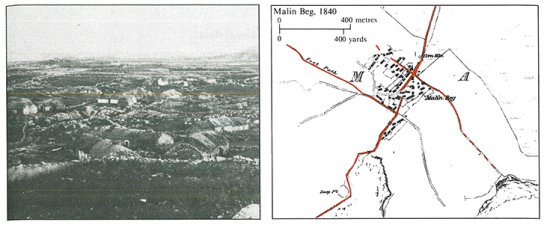

Killala seen from the harbour

Despite the gloomy picture painted by dramatic media accounts of the death throes of rural Ireland, this is only part of the picture, with many initiatives underway to address the issues highlighted here. It should also be acknowledged that some parts of rural Ireland are doing well, whether through tourism, the food industry or long-standing foreign multinational employment.

Killala seen from the harbour

Despite the gloomy picture painted by dramatic media accounts of the death throes of rural Ireland, this is only part of the picture, with many initiatives underway to address the issues highlighted here. It should also be acknowledged that some parts of rural Ireland are doing well, whether through tourism, the food industry or long-standing foreign multinational employment.

The CEDRA report made 34 recommendations to encourage a rural revival, one of which was implemented in July 2014 with the appointment of the first ever Minister for Rural Affairs, Ann Phelan. The problems of rural Ireland are possibly encapsulated in the full title of her post: Minister of State at the Departments of Agriculture, Food and Marine and Transport, Tourism and Sport with Special Responsibility for Rural Economic Development (implementation of the CEDRA Report) and Rural Transport. Like Father McDyer in 1950s Donegal, the Minister for Rural Affairs’ main focus will be on job creation. This includes encouraging the IDA and Enterprise Ireland to entice companies into smaller areas of population, as well as supporting agri-food and artisan businesses. The CEDRA report also recommends the creation of rural economic-development zones and a small-town stimulus programme.

More recently, in March 2015, the Save Rural Ireland alliance was launched with the intention of highlighting issues affecting the social and economic development of rural Ireland, and lobbying the government for reform. Its initial membership includes national bodies with common interests and a combined membership of 100,000, namely Muintir na Tíre, The Irish Cattle and Sheep Farmers’ Association, The Irish Countrywomen’s Association, the Irish Postmasters’ Union, the Irish National Flood Forum and the Post Office Users Group. Local infrastructure and services, specifically rural broadband, post office viability and GP cover, are among the immediate core issues identified by the group.

Other initiatives underway include the provision of third-level education through regional hubs, thereby halting the exodus of young people to attend colleges in urban centres, often never to return, while also increasing potential access to, and participation in, higher education.

Despite the many challenges presented, the demise of rural Ireland is exaggerated, though the challenges of peripherality remain. The uniqueness of each place yields certain opportunities to be harnessed, as Father McDyer recognised in the past, such as the potential saleability of rural distinctiveness and unique culture to tourists, or the promotion of artisan products. However, not everyone agrees as to the use of unique rural resources, as exemplified by debates and protests over pylons, pipelines, windfarms and fracking. Such controversies are likely to intensify in the future, as the intrinsic value of Ireland’s landscape heritage is set against potential economic gain. The material presented here, from the 1980s and updated to 2015, demonstrates how local places are not static, but constantly evolving and undergoing processes of reinvention. It also suggests that there are no ‘one size fits all’ solutions to the challenges facing peripheral areas.

This article, along with those on Southwest Donegal and Northeast Mayo, illustrates how different elements of society, from schools, shops, services, community groups to employers are linked together in particular places. It is also clear that wider links and interdependencies shape these places, from the ebb and flows of migration, to decisions taken by national government, European institutions or in the boardrooms of MNCs. The geographical method of synthesis, presented in the initial course presentation and in the 2015 update, helps to explain how places in rural Ireland retain their uniqueness within the evolving systems of interdependence. It also reveals the ongoing challenges of uneven development. While offering a useful way of exploring the issues facing the West of Ireland, the concepts of uniqueness and interdependence of place can also be applied beyond rural Ireland, with potential for explaining aspects of the geography of multiple locations around the world.

Further reading

You may wish to explore the following useful sources for further reading:

- http://muintir.ie/save-rural-ireland/

- http://www.irishcentral.com/news/irishvoice/Rural-Ireland-is-in-serious-trouble-.html

- http://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/people/behind-the-news-save-rural-ireland-campaigner-bernard-kearney-1.2138781

- http://www.independent.ie/irish-news/the-battle-for-rural-ireland-is-worth-winning-31049237.html (Richard Curran, March 2015)

- http://www.thejournal.ie/readme/column-its-time-to-tackle-decline-in-rural-ireland-818388-Mar2013/ John Verling article

- MacEinri, P. (2013) Irish Emigration in an age of austerity. UCC: Cork, http://www.research.ie/intro_slide/research-funded-irish-research-council-irish-emigration-age-austerity

- http://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/rural-ireland-can-she-fix-it-1.1898223 August 2014

Acknowledgements

This material draws from Open University programmes and a course based on the work of Pat Jess.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews