After all the haggling around the dinner table in Brussels, voters in Britain will now have to make their big choice. In a referendum to be held on June 23, they will either have to say they want to stay in the European Union on David Cameron’s renegotiated terms or indicate that they would prefer to leave.

For many voters this will not be an easy choice. New research based on NatCen’s latest British Social Attitudes survey reveals that scepticism about the EU is widespread. Yet at the same time, many are not sure about the wisdom of actually pulling out.

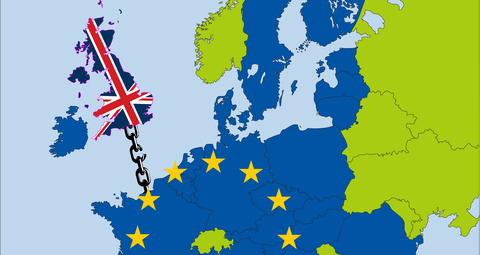

Heading for a European exit?

Heading for a European exit?

In the survey, of five different possible options for Britain’s relationship with the EU, the most popular by far, backed by 43%, was that Britain should remain in the EU but try to reduce its powers. That, of course, is precisely the sentiment to which Cameron has been trying to appeal through his renegotiation.

Another 22% said that Britain should leave the EU. If we put the two groups together, this means that nearly two-thirds of voters (65%) can be regarded as at least to some extent sceptical about Europe.

This scepticism expresses itself in a wish to curb much of the EU’s scope. For example, no less than 68% think that the ability of EU migrants to claim welfare should be reduced.

But it also extends to areas that Cameron has not attempted to renegotiate. For example, as many as 59% would want to stop people from other EU countries getting NHS treatment, a move that would undermine the reciprocal emergency access to another nation’s health service that all EU citizens currently enjoy.

Meanwhile, 51% want to end the automatic right of people in the rest of the EU to come to Britain to live and work. In other words they want to scrap the freedom of movement provisions that many in the EU regard as one of the cornerstones of the institution.

Nevertheless, when these very same respondents were asked whether they wanted Britain to “continue” to be a member of the EU or to “withdraw”, just 30% said “withdraw”. No less than 60% said Britain should maintain its membership.

Evidently there is something that persuades voters that scepticism about the EU is not necessarily sufficient reason to leave.

Sceptical … but not out

Much of voters’ scepticism is fed by cultural concerns about the consequences of membership – the perceived implications for Britain’s sovereignty and identity – concerns that have probably been heightened by the high level of EU immigration during the last decade or so.

Nearly half (47%) of all voters believe that Britain’s membership of the EU is undermining the country’s “distinctive identity”. And almost everyone who holds that view (86%) is a eurosceptic.

At the same time, however, many are wary of the economic consequences of actually leaving the EU. No less than 40% say that Britain’s economy would be worse off if it were to leave, while just 24% believe it would be better off – another 31% feel that perhaps it would not make much difference either way.

It is this wariness about the economic consequences of leaving that largely accounts for voters’ relative reluctance to back withdrawal from the EU. Among those who think the economy would be worse off if Britain left, just 6% actually support withdrawal. Even among those who think leaving would not make much difference, only 31% support want to head for the exit.

Only among the minority who think that the economy would be better off if Britain left is there substantial support for withdrawing. As many as 72% of this group back that option.

The implications for the two sides in the referendum race are clear. The Leave campaign cannot afford simply to rely on voters’ doubts and scepticism about the EU. It has to convince them that Britain would actually be better off economically if it left.

The Remain camp, meanwhile, has to persuade Britain’s sceptical voters that the prosperity delivered by the EU means its tendency to “meddle” in Britain’s affairs is a price worth paying.

In any event, expect to hear a lot more about the economics of the EU between now and June.![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews