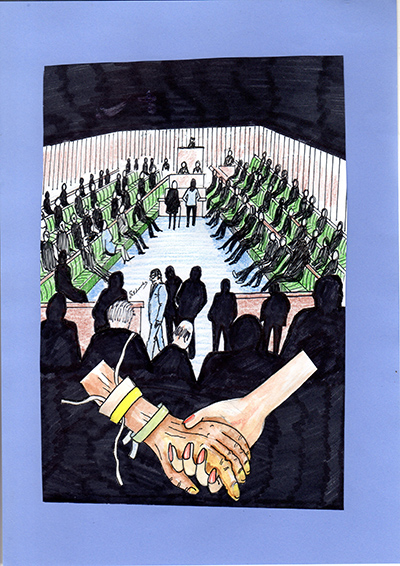

As the dust precariously settles on the parliamentary vote in September that rejected the “right to die,” I shake my head at the polarised debate that missed a trick. What we need is not the ability to hasten death, but a universal, intelligent and humane system that does not prolong a life of suffering. When Mother Nature says it’s time to go, we should be able to choose whether to acquiesce or rebel, whether to accept the inevitable or fight for one last hurrah. It might be that the legislation is already in place to allow this, but anecdotal evidence suggests it is, in practice, a grey area that serves no one well.

As the dust precariously settles on the parliamentary vote in September that rejected the “right to die,” I shake my head at the polarised debate that missed a trick. What we need is not the ability to hasten death, but a universal, intelligent and humane system that does not prolong a life of suffering. When Mother Nature says it’s time to go, we should be able to choose whether to acquiesce or rebel, whether to accept the inevitable or fight for one last hurrah. It might be that the legislation is already in place to allow this, but anecdotal evidence suggests it is, in practice, a grey area that serves no one well.

I have one anecdote of my own. My elderly dad was not in the best of health. For over a year he’d “had enough,” but we – my mother, siblings and I – cared for him and jollied him along as best we could. When his blood pressure and pulse suddenly plummeted, he was admitted to the local A&E where complete heart block was diagnosed. The solution, we were told, was a pacemaker. Knowing that any procedure, even a short hospital stay, would distress Dad, I asked if there was an alternative treatment including a do-nothing option. Nope. Everyone from the junior doctor to the consultant insisted that Dad needed a pacemaker; without it he could suffer for months; there was no choice.

So after a weekend in the local hospital (the NHS is not fully 24/7) my confused and upset Dad was taken on an hour-plus ambulance journey to a specialist heart unit (Mum and I made our own way there). The surgeon thoroughly assessed Dad then took Mum and me to one side and asked us quietly, “Do you want to go ahead?”

It was June 24th, my niece’s third birthday, Mum and Dad’s only granddaughter. Could Mum cope with, in effect, pulling the plug on Dad on what should be a celebratory day, forever to be tarnished? Coupled with the fact it had to be a quick decision – the surgeon practically had the scalpel in his hand – we said yes of course we did want to go ahead.

The insertion of the pacemaker was a medical success but a personal tragedy for Dad. He endured two more years of pain, confusion, immobility, indignity and misery, until he contracted complex dysphagia and stopped trying to eat or drink. In the meantime, Mum’s health suffered because of the physical and emotional strain; she was bed-ridden and almost hospitalised. It also affected my sister’s health because she had to suddenly care for both parents until I could return early from holiday to take some of the strain.

Dad’s final stay in his local hospital showed that the medical profession’s attitude had changed only a little regarding conversations about withholding life-prolonging treatment. Last time they were dismissive; this time they were embarrassed. The only advice they volunteered was that keeping him on a drip was “… not a long-term solution…” the “tion” resonating like a bad bout of tinnitus. The rest of the necessary information I extracted through careful questioning worthy of an experienced barrister. As a result, Dad came home – on his 88th birthday – with a package of care and pain relief, which is what should have happened two years previously.

This was not assisted dying but non-assisted living. His death was not artificially hastened, neither was his life artificially prolonged. Current legislation allowed this for Dad’s particular circumstances. Would it be allowed for others? It is this question that right-to-die campaigners and MPs should be asking.

This blog post is part of Society Matters. The blog seeks to inform, stimulate and challenge our understanding of this changing world and of our humbling role within it.

Want to know more about studying social sciences at The Open University? Visit the Social Sciences faculty site.

Please note: The opinions expressed in Society Matters posts are those of the individual authors, and do not represent the views of The Open University.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews

Paliments decision I imagine is based upon the wider legal & moral challenges which could be faced and I imagine this would lead to a lot of contention among society.

Personally I do think that people should have a choice over their life and how and if they chose to continue living it. We all have that choice everyday we live, but for those that are immobile, taking their life without assistance might be impossible which in turn regurgites my previous statement regarding legal & moral implications on those that assist.