One of the central arguments of my book Intercultural Communication is that, even today, much intercultural communication is approached from an orientalist perspective, i.e. a Eurocentric and colonial way of seeing people from other countries as stereotypes. Orientalism finds expression in a myriad of discourses and one way in which it is reproduced is through presenting “foreigners” as weird spectacles.

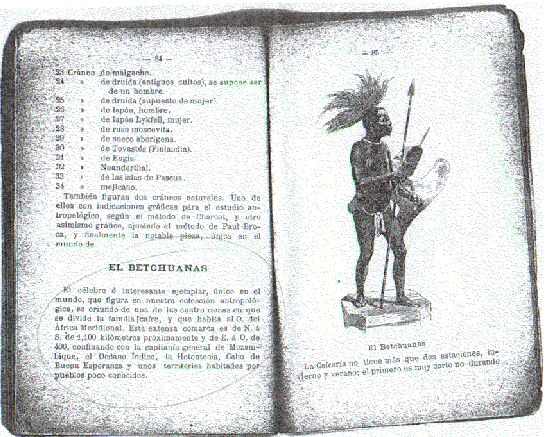

Picture of "El Negro" ("Negre de Banyoles", or "The Negro of Banyoles") published by Francesc Darder in a booklet for Barcelona Universal Exhibition at 1888

Picture of "El Negro" ("Negre de Banyoles", or "The Negro of Banyoles") published by Francesc Darder in a booklet for Barcelona Universal Exhibition at 1888

During the ages of European exploration and colonial expansion, the west delighted in viewing the wonders of the “new” world by collecting specimens of exotic animals, plants and cultural artefacts for display in zoos, botanical gardens and museums. The desire to collect and display “the exotic” did not stop at humans, either. For instance, in the 1830s a French merchant snatched the body of a young African man and stuffed it in the way animals are sometimes stuffed and prepared for display. The body was then shipped to Europe and displayed for almost two centuries in various museums. The body was removed from public display only in 2000, when the remains were repatriated to Botswana. If you are interested in learning more about the man behind the body, you will find this BBC article about “the man stuffed and displayed like a wild animal” as informative as it is disturbing.

Another way to turn foreign people into spectacles for the western gaze was to put actual people on display. For instance, in the collections of Heinrich Zille, an illustrator and photographer who documented the lives of Berlin’s poor in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there is a series of photographs of an amusement park festival, a “Rummel.” The photographs are ethnographic in the sense that Zille’s aim was to capture the perspectives of the common people who attended the festival. Many of the spectacles on display for the amusement of Berlin’s poor relate to “fremde Völker” (“foreign peoples”). Browsing through the photos, one notices an “Indian Pavilion”, one that displays “Roses from the South” (women in costumes), or another one that features “Sioux-Indians from the Island of [illegible].” In the displays, anthropological accuracy is obviously completely beside the point. While the name of the island, where the Sioux on display are supposed to come from, is illegible in the image, it obviously does not matter because the basic mistake is the claim to island residence. Furthermore, the painted image of a “Sioux” on the front of the tent is of a black person.

The image I find most haunting in the collection is of a tent displaying “Die Original Australier” (“the original Australians”). In front of the tent, three Aboriginal (or South Pacific?) men stand on display. They are wearing long white robes in the manner of Christian monks or possibly traditional Arabs. The headdress of two of them includes some feathers and the third wears a headdress that includes the horns of cattle. Again, accuracy is completely beside the point – do I even need to point out that cattle are not native to Australia and so could not have been part of traditional dress? One cannot but wonder what the three costumed men who are being gawked at make of their position. Their facial expressions seem withdrawn. How did these men from the Southern Hemisphere end up as display objects in a Berlin amusement park in 1900? What did they make of life in Wilhelmine Germany? Where did they die?

In addition to displaying real bodies and people as specimens of the “weird” Other, books, newspaper and paintings equally contributed to the exoticization of non-Europeans. The stalls photographed by Zille all also display painted images of and short slogans about the featured group. A vivid example of “textual display” comes from Robert Louis Stevenson’s collection of children’s verses “A Child’s Garden of Verses.” First published in 1885, the collection continues to be in circulation today. Wikipedia informs us that the collection “contains about 65 poems including the cherished classics ‘Foreign Children,’ ‘The Lamplighter,’ ‘The Land of Counterpane,’ ‘Bed in Summer,’ ‘My Shadow’ and ‘The Swing.’”

It is the “cherished classic” poem “Foreign Children” that positions the non-European Other as weird spectacles – objects of a mixture of pity and amusement:

Robert Louis Stevenson, “Foreign Children” (first published in 1885; a “cherished classic” in 2016)

Little Indian, Sioux, or Crow,

Little frosty Eskimo,

Little Turk or Japanee,

Oh! don’t you wish that you were me?You have seen the scarlet trees

And the lions over seas;

You have eaten ostrich eggs,

And turned the turtle off their legs.Such a life is very fine,

But it’s not so nice as mine:

You must often as you trod,

Have wearied NOT to be abroad.You have curious things to eat,

I am fed on proper meat;

You must dwell upon the foam,

But I am safe and live at home.Little Indian, Sioux or Crow,

Little frosty Eskimo,

Little Turk or Japanee,

Oh! don’t you wish that you were me?

Whether the poem presents any facts about “foreign children” is completely beside the point. That there are no lions or ostriches where the exemplars of “foreign children” in the poem live is beside the point. What the poem does – in the same way as the displays mentioned above – is to set the foreign Other up as weird spectacle. Ultimately, the point of the poem is not even about the Other but about the Self: the British child who reads the poem – or has the poem read to them – can feel reassured that they are safe, normal and proper – in contrast to all the imagined foreign weirdos out there.

The examples I have shared so far are over a century old and one might be tempted to dismiss them as the benighted ways of our forebears. We have certainly largely lost the appetite for putting real humans – whether alive or dead – on display. However, the proliferation of images of the cultural other as stereotypical spectacle continues unabated. Not only do texts such as the “Foreign children” poem continue to circulate but new texts presenting people as stereotypical representatives of a country and weird spectacle appear all the time.

For instance, the Australian supermarket chain Woolworths is currently running a marketing campaign aimed at children called “World Explorers.” The campaign is a collectibles program where shoppers can collect card sets. The front of each card is dominated by a cartoon character, who is clearly identified as a representative of a particular country. The back of each card contains two sections. One is titled “Have a go …” and consists of a one-sentence activity suggestion and the other is titled “Weird but true” and contains some random country fact. The cards can be flipped over and their insides reveals further sections, including “Did you know?”, which features another random country fact, “Food for thought”, which describes a national dish or food item, and a little section, where the character introduces him- or herself.

The character for Papua New Guinea, for instance, is a little girl who introduces herself as follows:

Gude! I’m Lani and I’m from the town of Tari, Papua New Guinea. It’s one of the few places in my country where we still regularly wear traditional dress.

The card also features an image of two tribal men, accompanied by this “Did you know?” explanation:

The Huli Wigmen, where I live, grow their hair long to make helmet-like wigs. They often paint their faces yellow too.

The purpose of the campaign is supposedly “to educate kids about the world and different cultures,” as the campaign website states. “Education” supposedly also was the aim of the exotic people displays from an earlier period. As I showed above, this was an “education” not in facts, knowledge, understanding and empathy but an “education” into a particular way of viewing the world: one where the foreign Other is always defined by their national identity and destined to offer a stereotypical spectacle for the western viewer. This spectacle of the “weird but true” Other may cause amusement, pity or disgust in the viewer but, above all, it is designed to bring home to the viewer their own essential difference from, if not superiority to, those exotic foreigners.

This article was originally published by Language On The Move under a CC-BY licence

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews