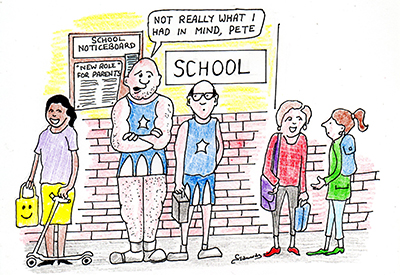

In what circumstances can you judge that a parent is “not good enough”? Apparently when they are a school governor. In its latest set of reforms in education, the government plans to scrap mandatory elected parent representation on school governing boards, so ending a democratic form of governance that has been in place since the late 1970s.

In what circumstances can you judge that a parent is “not good enough”? Apparently when they are a school governor. In its latest set of reforms in education, the government plans to scrap mandatory elected parent representation on school governing boards, so ending a democratic form of governance that has been in place since the late 1970s.

With this move, the government has gravely misunderstood not only what elected parents contribute to school governance, but also the legitimacy and credibility their involvement lends to the process of governing schools. The fact that parents are democratically elected onto boards epitomises the principles underlying a democratic system of education.

Parents were first brought onto governing bodies of schools after the 1977 Taylor report. This looked to transform school governance by ensuring that the public interest in schools was represented by local education authorities, staff, parents and the community who would “share as partners in promoting the success of that school, in all its life and work, and its good relationships with parents and the wider community”.

Yet with breathtaking arrogance, the government’s new white paper dismisses the role of elected parents as “tokenistic” and their role as purely “symbolic”. It looks to relegate them to something that sounds like a school-level cheerleader, who must now spend their time “focusing on understanding and championing the needs of pupils, parents and the wider local community.” Stating that the real work – of holding school leadership and management to account – will be done by “professionals”.

The proposals to remove the requirement to have elected parent governors on boards risks alienating the very communities whose interests the board purports to represent. It is a grave error of judgement on the part of the government.

The role of parent governors

Defining what elected parents do for a board is not easy, but then it isn’t easy to define what any individual board member does. They act as a whole board and are judged as such.

Anyone with any experience of governance will attest to the power and value of the lay question – commonly asked by individuals with an interest in the subject but not necessarily expertise. This was a point raised by many who gave evidence to the 2014 parliamentary investigation into school governing.

In addition, experience both within and outside the education sector indicate that “professionals” do not necessarily readily convert their skills into good governance as the recent furore over the Kids Club charity, and other, similar scandals have proved.

The “symbolic” element of any governance role, is important too. The public outcry caused by the chair of the Environment Agency’s absence during the recent floods powerfully illustrated just how core symbolic presence is to the task of governance.

When parents were first introduced onto governing bodies they brought much to the table – local knowledge, awareness of issues bubbling up within communities. Sometimes this has been dismissed as “over interest in their own kids' stuff”. But is it? I imagine headteachers could provide plenty of examples of how issues that bubble up anecdotally as part of parents’ unique interest in the school community have proved invaluable and useful in articulating and defining a broader and more generalised problem.

Hard to quantify

Teachers protest against the government plans outside Westminster Cathedral

But it is that indefinable quality that really doesn’t sit well with policy makers. That tacit knowledge that can’t be pinned down and is damn near impossible to evaluate, that is what elected parents bring to the table. Parents are not there because they are accountants, lawyers or HR professionals in their day jobs, but because they are interested in the school and eager to learn about this system that was for so long considered a “secret garden” and hidden from public scrutiny.

Teachers protest against the government plans outside Westminster Cathedral

But it is that indefinable quality that really doesn’t sit well with policy makers. That tacit knowledge that can’t be pinned down and is damn near impossible to evaluate, that is what elected parents bring to the table. Parents are not there because they are accountants, lawyers or HR professionals in their day jobs, but because they are interested in the school and eager to learn about this system that was for so long considered a “secret garden” and hidden from public scrutiny.

As any teacher will tell you: a student that is keen to learn will ask the most searching of questions. Parent governors often ask questions that some professionals will never think to ask, either out of “professional respect” for an individual’s office – particularly if they share the same professional field – or because they are afraid that the question may seem at worst too basic, or at best undermining.

A constant mantra of “putting parents first” infuses the new white paper. But it rings hollow in terms of the substance of proposals. For example, the paper insists that the growth of multi-academy trusts “will improve the quality of governance”, but offers little indication as to how.

Parents themselves do not appear to be buying into the rhetoric, believing that professionalised boards will be too far removed from the communities they purport to represent. This was illustrated recently by some of the responses to a recent guest post by Nicky Morgan on the Mumsnet website. One remarked that:

Academisation puts power in the hands of an executive head and a corporate board and that is IT … Our governors have all been removed in favour of the new executive board. Who have never even visited the village.

By removing elected parents from boards, the government not only removes a vital source of knowledge and democratic representation from the public service of education, they also remove a powerful symbol of community; one that lends both credibility and legitimacy to the board and its decisions. In so doing they risk the wholesale alienation of the very parents they frame as central to their education policy.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

This blog post is part of Society Matters. The blog seeks to inform, stimulate and challenge our understanding of this changing world and of our humbling role within it.

Want to know more about studying social sciences at The Open University? Visit the Social Sciences faculty site.

Please note: The opinions expressed in Society Matters posts are those of the individual authors, and do not represent the views of The Open University.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews