The Buncefield oil storage depot

In 2005, there was a large explosion and fire at an oil storage depot near Hemel Hempstead, UK. This is how the incident was described in a report from the Health and Safety Executive:

On the night of Saturday 10 December 2005, Tank 912 at the Hertfordshire Oil Storage Limited (HOSL) part of the Buncefield oil storage depot was filling with petrol. The tank had two forms of level control: a gauge that enabled the employees to monitor the filling operation; and an independent high-level switch (IHLS) which was meant to close down operations automatically if the tank was overfilled. The first gauge stuck and the IHLS was inoperable – there was therefore no means to alert the control room staff that the tank was filling to dangerous levels. Eventually large quantities of petrol overflowed from the top of the tank. A vapour cloud formed which ignited causing a massive explosion and a fire that lasted five days [Figure 7].

The HSE report goes on to comment (emphasis added):

Failures of design and maintenance in both overfill protection systems and liquid containment systems were the technical causes of the initial explosion and the seepage of pollutants to the environment in its aftermath. However, underlying these immediate failings lay root causes based in broader management failings:

- Management systems in place at HOSL relating to tank filling were both deficient and not properly followed, despite the fact that the systems were independently audited.

- Pressures on staff had been increasing before the incident. The site was fed by three pipelines, two of which control room staff had little control over in terms of flow rates and timing of receipt. This meant that staff did not have sufficient information easily available to them to manage precisely the storage of incoming fuel.

- Throughput had increased at the site. This put more pressure on site management and staff and further degraded their ability to monitor the receipt and storage of fuel. The pressure on staff was made worse by a lack of engineering support from Head Office.

As the case study clearly shows, the Buncefield incident had multiple causes that illustrate the domino effect well. There was a lack of management, there were technical issues, other human factors were present, and they coincided in a chain of events that led to the largest explosion in peacetime Europe. Some of the issues were engineering problems – faulty switches and gauges – but their interaction with operators, and the management of technical equipment, was equally important in determining the cause(s) of the incident.

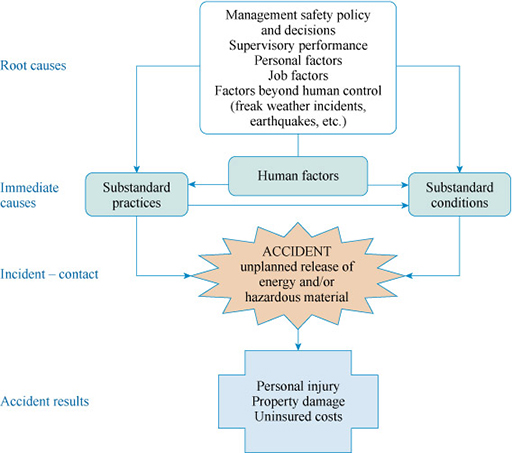

Whatever view of the causal structure of incidents is taken, the aim should be to look beyond the obvious cause and identify more fundamental ways of eliminating the hazard or reducing the risks by looking at multiple causes and their interactions. Figure 8 puts this into context.

Starting from the accident result at the bottom of the figure, notice that an accident resulting in personal injury or property damage, for example, may be attributed to an unplanned release of energy or material, as discussed previously. However, the root cause of the incident can be human error or management failure, through aspects such as lack of training or supervision.