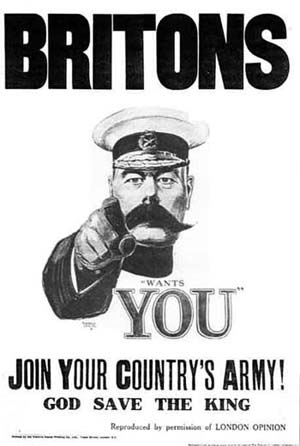

Offering the government a bracelet for to re-fashion into a bullet wasn’t an unusual gesture in 1915. If Britons weren’t putting their lives in the line, many felt compelled to make financial sacrifices to help pay for the war. With most taxable economic activity suspended, the country had to finance much of its military spending by issuing long-term debt. While “Your Country Needs You” might not have been the slogan that mobilised a million troops, the Treasury struck gold with its own marketing campaign - inducing people to buy its bonds more as a patriotic duty than a profitmaking investment. Much of the debt it issued was undated – meaning there was no obligation ever to pay the lenders back. Although it did eventually redeem the bonds, up to a century later, inflation had munched away much of their value by that time.

Offering the government a bracelet for to re-fashion into a bullet wasn’t an unusual gesture in 1915. If Britons weren’t putting their lives in the line, many felt compelled to make financial sacrifices to help pay for the war. With most taxable economic activity suspended, the country had to finance much of its military spending by issuing long-term debt. While “Your Country Needs You” might not have been the slogan that mobilised a million troops, the Treasury struck gold with its own marketing campaign - inducing people to buy its bonds more as a patriotic duty than a profitmaking investment. Much of the debt it issued was undated – meaning there was no obligation ever to pay the lenders back. Although it did eventually redeem the bonds, up to a century later, inflation had munched away much of their value by that time.

Today it’s a lot harder for governments to make the public part with its cash, even if they’re borrowing to fund hospitals, schools and other public services rather than war. It’s widely believed that people on lower incomes believe they pay too much tax, and by 2004 fewer than 1 in 3 people supported redistributive taxation. That’s not surprising, when the share of national income taken by government revenue rose from 9% in 1900 to 40% in 2000, with many now paying an income tax once initially confined to the rich.

And there’s now equal unhappiness about the scale of public debt, run up to fill the gap between what governments have collected in tax and what they’ve spent. After the bail-out of big banks that nearly crashed during the Global Financial Crisis, and the shrinkage of the tax-base in the downturn that followed, UK public debt has reached 85.8% of GDP. That’s perilously close to the 90% of GDP, above which public debt can become a serious constraint on the economy’s future growth, according to influential economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff.

Beg, Print or Borrow

Unusually, though, other economists have stepped in to dispel this gloom.

First, Reinhart and Rogoff got it wrong. At least, their claim that higher debt causes slower growth has been strongly disputed. That’s not just because causation might run the other way – governments only borrowing more when growth is slow. It’s also because the authors made a mistake on their original calculation, which a sharp-eyed student discovered when trying to replicate their result. If you ever get into trouble for misreading the numbers on a spreadsheet, remember this. A famous former World Bank chief economist also did this, and it didn’t stop him becoming one of the most authoritative commentators on global affairs.

Second, it may no longer be true that governments have to finance all their spending through taxation or borrowing. That was the case a century ago, when governments were still trying to stick to some form of ‘gold standard’ that tied the value of their money to stocks of gold (or to a US dollar that was exchangeable for gold). But today, released from such ties, governments with sovereign currencies can issue as much as they want. So if the UK government wants to spend more, it can do so without taxing or borrowing. It just gets the central bank to put the money into accounts at private-sector banks, whose lending creates the rest of the money the economy needs.

Magical Modern Money

This doesn’t mean that governments can spend with no constraint, or that voters and backbenchers can safely sleep through the Chancellor’s annual Budget. If they spend much more than they take in tax, governments can cause inflation. So they may need to issue debt as a way to keep prices stable. In an open economy like the UK, higher inflation can push down the exchange rate, making foreign debts much harder to repay. But inflation hasn’t taken off, despite unprecedented amounts of money-printing by central banks since the financial crisis. So Modern Money Theory (MMT), which claims that governments (and their social-security and pension funds) can never run out of money if they retain a sovereign currency, has moved from the fringes of economics to be taken seriously by the mainstream.

While MMT was at first associated with the political left, centrist and conservative governments are emerging as its major beneficiaries. The Trump administration, which chastised its predecessors for letting US public debt expand above $19 trillion, has already lifted it to $21 trillion after approving tax cuts which - with no matching spending reduction – create a trillion dollar federal budget deficit. The UK government has quietly abandoned the idea that public debt would put an overwhelming brake on the economy if it didn’t balance the budget and start reducing its debt by 2015. It is now set to run deficits at least until 2019/20, and the Office for Budget Responsibility has raised doubts on whether long-term budget balance is possible especially after unfunded health-service spending increases announced in June.

But that doesn’t spell imminent disaster, if Japan – where public debt is almost 240% of GDP – is any guide. In fact, if we’re not exporting capital, private sector saving requires government borrowing. So the Treasury may have to keep running deficits so that households can start to pay down their own historically high debts. In effect, governments are borrowing so that we don’t have to. Time, perhaps, to dust off that wartime bracelet and return it to the sender.

This article links to our Open University co-production Economics with Subtitles, in partnership with the BBC on Radio 4.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews