Kerr also manages the media production unit and Glasgow’s FutureLearn MOOCs (massive open online courses). The different relationships between these responsibilities and the way that they are supported at a College and School level mean that rather than a “very distributed” model, Glasgow has a “hub, hub, spoke” approach which connects different aspects of work whilst enabling a view from the centre. The aim of Glasgow’s approach is to be sustainable, supportive of the “local touch”, and have practice “embed[ed] in the curriculum rather than creating silos.”

Perceptions of OER

Kerr explained the importance of open educational practice (OEP) and constantly “thinking open” when looking to integrate open education into institutional practice:

“I think particularly in many areas of academia … the academic staff don’t always see how to buy into the OER – by OER I mean the conception that many people have, certainly that I’ve come across, of OER is – you create a learning object, you build a learning object and then you make it available. And then you look go and look for other people’s learning objects and use them. And it’s always seen as being quite clunky. I think the usage of some of the repositories like JORUM… their usage has been around that the fact that it’s not really captured the imagination. My experience with doing a MOOC at Glasgow has been that there is actually a real need for open education but it’s not actually so much concentrated in creating resources … it’s actually about thinking open when you come to practice. And what that then allows is a real business case to be made.”

Kerr highlighted some issues that individuals encounter when looking for or (re-)using open educational resources (OER). For example, being unaware of licensing implications can result in inappropriate reuse of material. Similarly found content can be inappropriate to share or reuse because of restrictive licensing/copyright. These issues are becoming more common as course content is made more widely available. Examples such as these also support the “business case” for open that Kerr highlighted above: if you build things that are ‘open’ from the outset (such as MOOC or other online courses) then they can be repurposed or reused elsewhere.

“If you can think open initially, then the content you create you’ve got much more flexibility with it … that whole concept of thinking more fundamentally about open practices – everything we do should be available – and also thinking then about what we do as a University, for me it brings out more opportunity to be open…”

MOOCs at University of Glasgow

Following institutional agreement to participate Kerr led the development of FutureLearn MOOCs at the University of Glasgow. MOOCs, which Kerr described as “a type of delivery”, fit with and are one contributing factor to the overall university strategic objective to engage more with online learning and what Kerr described as “embracing that evolving digital landscape.” The process of developing the first MOOC was deliberately flexible and initially “we didn’t have any real preconceptions about what we wanted out of” developing and running the first courses.

The initial process for MOOC development was a non-targeted one with a call for staff involvement and a lot of subsequent interest from colleagues. Although few bids were ultimately submitted in response to the first call, it was early days for the FutureLearn platform (which was still in development) so this and the potential unknowns around involvement may have impacted on potential submission. Later calls for participation were structured similar to that employed by FutureLearn, e.g. why this topic, why might people want to sign-up etc.

The University of Glasgow’s first two MOOCs launched in summer 2014: Cancer in the 21st Century: The Genomic Revolution and Right Vs Might in International Relations. You can read a report on their implementation Building and Executing MOOCs.

Following the facilitation of the first MOOCs a period of reflection on this process followed. Kerr made a number of observations:

- MOOCs are costly to both make and run. The first Glasgow MOOCs were six weeks long and ran twice a year. Each MOOC requires around 8 weeks of academic time. The intensive amount of academic time required to run a MOOC necessitated a review of sustainable models of facilitation. As Kerr noted later on the process of looking at which MOOC run is based on: “…how is it going to be resourced, how is it going to be sustained to run several times, possibly several times a year … and then looking at how it fits in with what we’re trying to do.” One of the first MOOCs for example was very time specific and focused on drones and modern warfare, to redo the course would require a “brand new rewrite,” the time required to do this made further iterations unsustainable.

- MOOCs can be used for both recruitment and research purposes, e.g. the “crowdsourcing of data for research.” There is also a strong sense of MOOCs offering avenues for dissemination, as recognised by funding bodies such as the AHRC. As Kerr explained: “MOOC can take that research and in effect, in developing a MOOC, you’re developing for a wider audience.”

- In instances where MOOC are built into another course, there can be the challenge of accreditation and the relation between the different platforms that are in use (at the University of Glasgow Future Learn is separate to the institution’s virtual learning environment (VLE), for example). Kerr recommended not accrediting the MOOC but accrediting the course module to ensure that quality assurance issues were addressed.

- Kerr noted that MOOCs offer the possibility to broaden the experiences of campus based students and widen participation simultaneously. For example targeted cohorts of people could be encouraged to study a particular iteration of a course alongside University of Glasgow students. This approach could facilitate and broaden people’s experiences, encourage cross-fertilisation and “widen element[s] of [a] course out and get engagement from other people.”

- MOOC can also be a way of “showcasing” different facets of an institution. One such example at University of Glasgow is the Robert Burns MOOC which was launched on 25 January 2016.

Lessons Learnt: Challenges/Reflections on creating and developing MOOC

Kerr reflected on perceptions of the pedagogy of developing open resources and MOOC. Whilst there may be a need for additional resources at this point in time, from Kerr’s perspective we are ultimately “in a transition period” whilst moving toward a more online and blended teaching model that “…break[s] those barriers between campus and distance and then between face-to-face and virtual or online…”

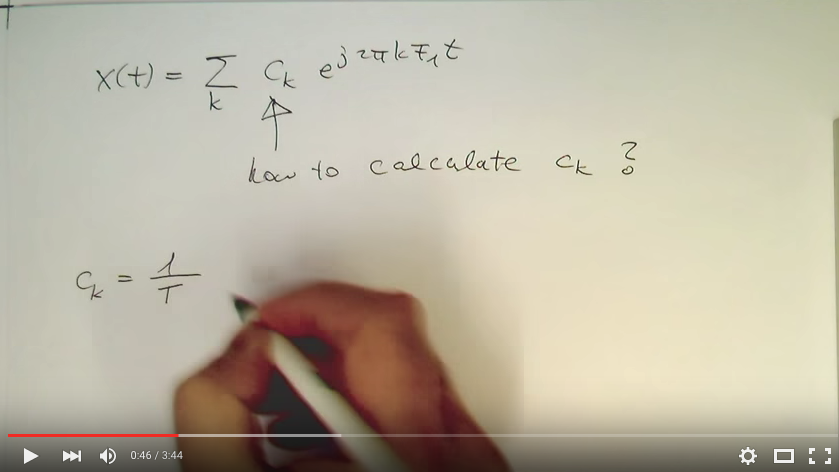

“…I think there is still, and this is talking to colleagues around the sector who are engaged with MOOCs, I think there is still a perception in UK HE that online learning is basically copying and pasting what you do in the classroom. Not everywhere … but I think overall there is a perception about it. I think people don’t really quite understand how much effort it takes to develop a MOOC.

My own thoughts on that are … because they haven’t actually created an online course they don’t really have the knowledge or the experience to work out how long it will take. For developing online there’s an element of ‘how long’s a piece of string’ particularly for creating video work and other types of rich media. I think there’s a whole copyright area where the people are quite aware of what they can do within the physical classroom or even an online classroom but where it’s limited by it’s only your students that actually have got access to it so everything’s in a controlled area. Many of the resources we use in higher education are available for that closed cohort but not for the open. So there’s that whole thing where people are working with the method they have used for many years, in many cases, within the university structure. And now in effect it’s creating a totally open course and the rules are different.

I think working out why to do a MOOC and what’s in it. I think the realisation, even centrally … how much on-going effort I was actually going to be going to be… I think also … it’s not that online necessarily takes longer to develop than a face-to-face but I think that when if you’re developing a face-to-face it’s what you’ve always done so that you’ve got a whole lot of experience on what kinds of things you do in a face-to-face environment, you’ve go the subject matter and quite often you’re not actually creating things necessarily totally from scratch and particularly if you’re doing a traditional lecture, you don’t have to create all the stuff in advance… whereas for something like a MOOC or even online learning it’s a different environment you’re working in …”

There is no one solution to enable this “transition period” to progress as so many different factors are involved. As Kerr put it:

“…What is that magic bullet? … The more that I’m engaged with this the more I think there just isn’t actually one. Because there’s a range of things: there’s cultures, there’s ethos, there’s structures within the education sector … institutional capability…”

Impact of MOOCs across University

“…It is one of the hidden benefits. It is upskilling the University in its knowledge, its ability, its awareness and everything else around it.”

Although it is difficult to isolate the specific impact of MOOC within the context of learning and teaching as a whole, Kerr did note that MOOC had both “…become much more part of the discussion” and been a factor in making the financial case for other online courses. MOOC also had an important role to play in widening participation:

“The perception is that they’re [MOOC learners] mainly traditional male, 25-35… is that very narrow demographic … it’s already people with degrees and so on. But actually the FutureLearn data ... there’s something like 24-25% that record their highest educational achievement as secondary school. And that to me is actually pretty good coverage…”

The University of Glasgow’s strategy of looking forward to not just the next 5 or 10 years, but the next 50 to 100 years was also helping facilitate innovation, particularly as the University is currently building a new Learning and Teaching Hub, redeveloping it’s learning and teaching strategy and discussing how best to use an additional 18 acres of land in the West End of Glasgow effectively. As Kerr noted “it allows you to think out the box a bit more, and think things a bit more holistically.” Further MOOCs are also in the pipeline with the focus on sustainability and MOOC existing as “part of the general offering”.

Photo credits:

Photograph of Glasgow University by Mike Peel (www.mikepeel.net). [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Photograph of Kerr Gardiner via Twitter

Tape Measure (CC-BY 2.0, Beck Pitt)

Originally published on 22 April 2016 - 11:31am by Beck Pitt