Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 25 April 2024, 1:41 AM

Communicable Diseases Module: 35. Acute Respiratory Tract Infections

Study Session 35 Acute Respiratory Tract Infections

Introduction

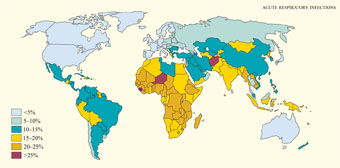

In this study session, you will learn about acute respiratory tract infections (ARIs). The respiratory tract (or ‘airways’) includes all the parts of the body that enable us to breathe. ARIs are infections of the respiratory tract by either bacteria or viruses, and the term ‘acute’ indicates that the illness is of short duration (less than two weeks). ARIs are the leading cause of illness and death among young children everywhere in the developing world (Figure 35.1). Ethiopian children suffer four to eight episodes of ARI on average every year, with the highest occurrence in urban areas in overcrowded living conditions. In rural Ethiopia, 20% of the deaths of children aged under five years and more than 30% of the infant deaths under one year are due to ARIs. A better knowledge of ARIs will enable you to detect children with an ARI more quickly and give appropriate treatment, or refer them if the disease is severe.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 35

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

35.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQs 35.1, 35.2, 35.3 and 35.5)

35.2 Identify the common causative agents, modes of transmission and risk factors for the common acute respiratory tract infections (ARIs): acute otitis media, pharyngitis and pneumonia. (SAQs 35.1, 35.2 and 35.5)

35.3 Describe the clinical presentations and complications of ARIs, and the danger signs of severe pneumonia, and explain how these conditions should be managed. (SAQs 35.2, 35.3 and 35.4)

35.4 Explain the most effective ways to prevent and control ARIs, including through community education. (SAQs 35.2 and 35.5)

35.1 What are acute respiratory tract infections?

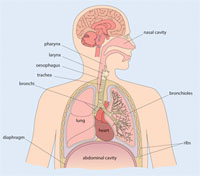

Acute respiratory tract infections (ARIs) are bacterial or viral infections of the respiratory tract leading to breathing difficulties, fever and other complications, including infections in the ear and the membranes surrounding the brain. ARIs are classified according to whether they affect the upper or lower respiratory tracts (Figure 35.2). The upper respiratory tract consists of the airways from the nostrils to the vocal cords in the larynx (voice box), and includes the pharynx (back of the throat) and part of the internal structure of the ear (the middle ear). The lower respiratory tract refers to the continuation of the airways below the larynx and the branching airways throughout the lungs.

Upper respiratory tract infections (URIs) are the most common of all communicable diseases. They are transmitted from one person to another by airborne droplets spread through coughing or sneezing. URIs include mild self-limiting infections such as the common cold (rhinitis), and more severe acute infections in the ear (acute otitis media), or in the pharynx (pharyngitis). Lower respiratory tract infections (LRIs) are the leading cause of pneumonia, which will be described in Section 35.4 of this study session. First, we discuss acute otitis media and then pharyngitis, both of which can cause severe complications in children.

Rhinitis is pronounced ‘riy-niy-tiss’; otitis is pronounced ‘oh-tiy-tiss’; pharyngitis is pronounced ‘fah-rin-jiy-tiss’.

35.2 Acute otitis media

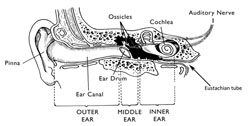

Acute otitis media (AOM) is a severe infection of the middle ear (Figure 35.3), lasting less than two weeks. It is very common in babies and young children, but is rarely seen in adults. Studying this section will help you to prescribe the necessary treatments to a child with AOM, and know when to make a referral of more complicated or persistent cases for further investigation and specialist treatment at a higher level health facility.

It may surprise you to learn that infection inside the ear is classified as a URI. The explanation can be found in Figure 35.3. In each ear, the middle and inner ear are connected to the upper respiratory tract by a tube called the Eustachian tube, which leads to the pharynx. You can sometimes hear a soft ‘pop’ in your ears when you swallow as the pressure wave created by swallowing travels up the Eustachian tubes. Upper respiratory tract infection in the pharynx and tonsils can reach the middle ear if the infectious agents spread upwards along the Eustachian tubes.

35.2.1 How does acute otitis media affect hearing?

In normal situations, the middle ear is filled with air, which transmits sounds from the outside world to tiny bones (called the ossicles, see Figure 35.3), causing them to vibrate. The vibration generates signals which the auditory nerve transmits to the brain. This process enables us to hear the sounds. If infection reaches the middle ear, the lining becomes red and inflamed, and it leaks sticky tissue fluid (mucus) into the ear. As the infection builds up, white blood cells crowd into the area to fight the infectious agents and the middle ear becomes filled by pus – a thick whitish-yellowish fluid, formed by mucus packed with living and dead bacterial cells and debris from damaged tissue in the ear.

What effect do you think pus in the middle ear will have on normal hearing, and why?

It is likely to impair hearing, because the thick, sticky pus stops the ossicles from vibrating properly, so sounds are not transmitted to the brain in the normal way.

35.2.2 Causes, transmission and risk factors for acute otitis media

The two predominant bacteria that cause otitis media include Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type b, both of which can be prevented by immunization. It can also be caused by a viral vaccine-preventable disease, which you learned about in Study Session 4 of this Module.

Immunization against bacterial infections caused by Haemophilus influenzae type b is included in the routine EPI schedule for all children in Ethiopia; immunization against Streptococcus pneumoniae infection will become available soon.

Can you recall which vaccine-preventable disease is transmitted by airborne droplets and may lead to acute otitis media (AOM) as one of its complications?

Measles is associated with several complications in young children, including AOM and pneumonia.

AOM is transmitted by airborne spread of the causative infectious agents in droplets, sprayed into the air when a sick person coughs or sneezes. The infection in the new host usually begins with a common cold, sore throat or measles.The presence of certain risk factors makes babies and young children more vulnerable to developing AOM (see Box 35.1).

Box 35.1 Risk factors for acute otitis media

- Age: most cases are below five years of age

- Family history of otitis media

- Winter season

- Living in overcrowded conditions where other children have coughs or runny noses

- Indoor air pollution from cooking fires (Figure 35.4) and/or tobacco smoke

- Bottle-feeding a baby (breastfeeding offers some protection from URIs)

- Poor nutrition, particularly when the child is not exclusively breastfed

- HIV-infection in the child.

35.2.3 Clinical manifestations, diagnosis and complications of acute otitis media

The symptoms and signs of AOM are highly variable, especially in infants and young children. As a health worker in the community, you should check the following symptoms in children with upper respiratory tract infections:

- Ear pain, often manifested by irritability (the child is easily upset) and occasionally holding or tugging at the ear

- A change in sleeping or eating habits

- Symptoms associated with upper respiratory tract infection, such as a runny nose and sneezing typical of the common cold

- Hearing loss, which may manifest as changes in speech patterns; however, this often goes undetected if hearing loss is mild or in one ear only, especially in younger children.

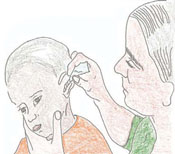

You can diagnose AOM by careful history-taking and physical examination. Ask the child’s caregiver about any history of the above symptoms of AOM. Examine the ear thoroughly for redness or pus discharging from the ear canal (Figure 35.5).

Acute otitis media may progress to produce other complications. These include chronic otitis media, manifested by pus discharging from the ear for more than two weeks, which can lead to permanent deafness.

What is the complication called if the bacteria that cause otitis media infect the membranes surrounding the brain? How serious is this complication?

You learned in Study Session 3 in Part 1 of this Module that bacterial meningitis is a potentially life-threatening infection of the brain, which can also spread and cause an epidemic.

35.2.4 Treatment of acute otitis media

As a Health Extension Practitioner you need to know how to treat acute otitis media. Treat the child as an outpatient in the Health Post or at home. Give oral co-trimoxazole or amoxicillin for five days. The dose of these antibiotics in tablets or syrup preparations depends on the age or weight of the child, as given in Table 35.1. These dosages also apply to the treatment of pneumonia, which will be discussed in Section 35.4 of this study session.

| Age (weight) | Co-trimoxazole (give twice per day for five days) | Amoxicillin (give three times per day for five days) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult tablet (80 mg trimethoprim + 400 mg sulphamethoxazole) | Paediatric tablet (20 mg trimethoprim + 100 mg sulphamethoxazole) | Syrup (80 mg trimethoprim + 400 mg sulphamethoxazole /5 ml) | Syrup (125 mg/5 ml) | |

| 2–12 months (4–10 kg) | ½ tablet | 2 tablets | 5 ml (1 teaspoon) | 5 ml (1 teaspoon) |

| 12 months to 5 years (10–19 kg) | 1 tablet | 3 tablets | 7.5 ml (1.5 teaspoons) | 10 ml (2 teaspoons) |

The assessment and treatment of ear infections in children is described in more detail in the module on Integrated Management of Newborn and Childhood Illness (IMNCI).

If the child has ear pain or high fever (equal to or above 39°C or 102.2°F), which is causing distress, give 5 ml of paracetamol syrup up to three times per day.

If there is pus draining from the child’s ear, show the mother or another caregiver how to dry the ear by wicking (cleaning the ear using a twist of very clean cotton). Advise her to wick the ear three times daily, until there is no more pus (Figure 35.6). Tell the mother not to place anything in the ear between wicking treatments. Do not allow the child to go swimming or get water in the ear. If the pus continues to discharge from the ear after five days, refer the child to a health centre for further assessment and treatment.

Strategies for the prevention and control of acute otitis media, pharyngitis (the subject of the next section) and pneumonia (described in Section 35.4) are the same, and will be described at the end of this study session.

35.3 Pharyngitis

Pharyngitis refers to infection and inflammation (becoming hot, swollen and red) of the structures in the pharynx. In most cases, the tonsils are affected and become inflamed and ulcerated (tonsillitis). In this section, we will describe the clinical manifestations, complications and treatment of pharyngitis. A better understanding of these points will help you to identify a child with pharyngitis and know that you should refer them to a higher level health facility. Pharyngitis can be caused by viruses or bacteria, but the most important causes are bacteria of the type known as Group A Streptococci. Infection with Group A Streptococci is common among Ethiopian children. It can lead to severe complications, including heart disease.

35.3.1 Clinical manifestations and complications of pharyngitis

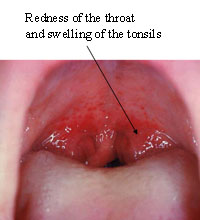

Pharingitis generally begins with the sudden onset of fever (temperature above 37.5oC, measured with a thermometer in the armpit), and a sore throat, with redness and swelling of the tonsils at the back of the throat (Figure 35.7). Other symptoms include headache, cough, runny nose and pain during swallowing.

Infection of the pharynx by Group A Streptococci has many complications, which include otitis media and throat abscesses (swelling containing pus). In a minority of severe cases, a form of heart disease – called rheumatic heart disease – can develop as a result of the body’s attempt to fight the infection. The immune system recognises Group A Streptococci as ‘foreign’ and produces antibodies that attack the bacteria. Antibodies are specialised proteins made by specific white blood cells as part of the body’s defence against infection. However, in rare cases, the antibodies produced to fight Group A Streptococci can attack the heart muscle of the infected child. As a result, these children can develop rheumatic heart disease later in life.

35.3.2 Referral of children with pharyngitis for treatment

![]() If you identify children with pharyngitis, you should refer them to the nearest health centre or hospital for specialised assessment and treatment.

If you identify children with pharyngitis, you should refer them to the nearest health centre or hospital for specialised assessment and treatment.

Educate mothers and other caregivers about the symptoms of acute otitis media and pharyngitis, and advise them to bring their child to you, or go to a health centre, if they suspect either of these conditions. Early diagnosis and correct treatment greatly improve the outcomes and reduce the risk of complications. Pharyngitis due to Group A Streptococci should be treated by doctors using a drug called Benzathine penicillin. This drug is given in the form of an injection, which is not authorised for use at Health Post level.

35.4 Pneumonia

A better understanding of pneumonia will help you to save many lives through early diagnosis and treatment or referral of cases, especially among children, and educating your community on effective prevention and control measures.

35.4.1 What is pneumonia and what causes it?

Pneumonia is a lower respiratory tract infection that mainly affects the lungs. The lungs are made up of small sacs called alveoli, which are filled with air when a healthy person breathes in. When an individual has pneumonia, the alveoli are filled with pus and fluid, which makes breathing painful and limits the amount of oxygen they can take into the body. Pneumonia is caused by a number of infectious agents, mainly by certain bacteria and viruses (Box 35.2). In children or adults whose immunity is weak, other organisms such as fungi can cause a rare form of pneumonia, which may be responsible for at least one quarter of all pneumonia deaths in HIV-infected infants.

Box 35.2 Major bacterial or viral causes of pneumonia

Bacterial causes (the major causes of death from pneumonia)

- Streptococcus pneumoniae – the most common cause of bacterial pneumonia.

- Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) – the second most common cause of bacterial pneumonia.

Viral causes

- Respiratory syncytial virus – the most common viral cause of pneumonia.

Pneumonia is the number one cause of death among children in Ethiopia and worldwide: globally, it causes an estimated 1.6 million child deaths every year. It is also among the top five causes of illness and death in adults in Ethiopia. The Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (DHS, 2005) estimated that 13% of children had pneumonia during the survey year, and infants (children up to one year old) were more likely to have pneumonia than older children under the age of five.

Viral infections often come on gradually and may worsen over time. The common symptoms include cough, fever, chills, headaches, loss of appetite and wheezing.

Which of the bacterial causes of pneumonia can be prevented by immunization?

You learned in Study Session 3 (in Part 1 of this Module) that vaccines exist to protect children from bacterial pneumonia caused by Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) or Streptococcus pneumoniae. The Hib vaccine is already routinely given to infants in Ethiopia, and the pneumococcal vaccine will be added to the routine EPI schedule in the near future.

Details of vaccines in the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) in Ethiopia are given in the Immunization Module.

As we mentioned earlier, immunization against measles also helps to protect children from complications, which include pneumonia and AOM.

35.4.2 Pneumonia transmission and risk factors

The infectious agents causing pneumonia may reach the person’s lungs through different routes. The most common modes of transmission are:

- Airborne droplets spread when the sick person coughs or sneezes, and inhaled into the lungs (breathed in) by a susceptible person;

- Direct oral contact with someone who has pneumonia (e.g. through kissing).

- During or shortly after birth, babies are also at higher risk of developing pneumonia from coming into contact with infectious agents in the birth canal, or from contaminated articles used during the delivery.

These modes of transmission help to explain why certain risk factors increase the probability that children or adults will develop pneumonia. Box 35.3 summarises the common risk factors, some of which also increase the patient’s susceptibility to fatal complications if pneumonia occurs.

Box 35.3 Common risk factors for pneumonia

- Under-nutrition/malnutrition, which weakens the immune system and reduces resistance to infection

- Inadequate breastfeeding or formula feeding of infants under six months old, which predisposes them to malnutrition and infection

- Lack of immunization against vaccine-preventable diseases that affect the respiratory system

- Infection with HIV and/or tuberculosis

- Living in overcrowded homes, where airborne infection is easily transmitted

- Exposure to indoor air pollution, especially smoke from cooking fires burning vegetable and animal waste (e.g. dried cow dung), which irritates the lungs and makes it easier for bacteria and viruses to gain a hold.

35.4.3 Diagnosis and classification of pneumonia

Children with pneumonia may have a range of clinical presentations, depending on their age and the cause of the pneumonia. Children who have bacterial pneumonia usually become severely ill and show the following symptoms:

- Fast or difficult breathing (see Table 35.2)

- Cough

- Fever and chills

- Loss of appetite

- Wheezing.

Adults with pneumonia also have fever, cough, and fast or difficult breathing.

| If the child is aged: | The child has fast breathing if you count: |

|---|---|

| 2 months to 12 months old | 50 breaths or more per minute |

| 12 months to 5 years old | 40 breaths or more per minute |

In severe cases of pneumonia, children under five-years-old may struggle to breathe and usually show chest in-drawing, which you can observe as drawing inwards or retracting of the lower chest (red arrows in Figure 35.8) during inhalation (taking air into the lungs).

Pneumonia in children and adults is classified into non-severe and severe pneumonia based on the features of the condition summarised in Box 35.4. This classification is very important because it determines what treatment is given to the patient (as you will see in Section 35.4.4).

![]() A child with fast breathing, chest in-drawing or stridor should be immediately referred to hospital.

A child with fast breathing, chest in-drawing or stridor should be immediately referred to hospital.

Box 35.4 Severe signs of pneumonia in children and adults

Children

- Age less than 2 months

- Presence of general danger signs (unable to drink or eat, lethargic or unconscious)

- Chest in-drawing

- Stridor (a harsh noise made during inhalation)

- Respiratory rate exceeding the limits in Table 35.2.

Adults

- Age 65 years or older

- Respiratory rate equal to or greater than 30 breaths per minute

- Presence of confusion.

If a child with pneumonia has fast breathing (Table 35.2), but no general danger signs, or chest in-drawing, or stridor, classify him/her as having non-severe pneumonia. Adults with pneumonia who do not have the severe signs given in Box 35.4, are also classified as having non-severe pneumonia.

35.4.4 Treatment of pneumonia

![]() Infants less than two months old with pneumonia may have serious complications such as meningitis and may die soon. Refer them urgently!

Infants less than two months old with pneumonia may have serious complications such as meningitis and may die soon. Refer them urgently!

Severe pneumonia in children and adults is diagnosed if they exhibit the signs summarised in Box 35.4. You should refer all patients with severe pneumonia immediately to the nearest health centre or hospital, where appropriate drugs can be prescribed by doctors or health officers.

For adults with non-severe pneumonia, give amoxicillin tablets, 500 mg three times a day for seven days. Details of the treatment of severe and non-severe pneumonia in children are given in a separate Module on the Integrated Management of Newborn and Childhood Illness (IMNCI). Here we remind you of the oral antibiotics you can give children with non-severe pneumonia without any other danger signs. The course of treatment is for five days with either co-trimoxazole (the preferred antibiotic drug), or if co-trimoxazole is not available, give amoxicillin. The doses of co-trimoxazole or amoxicillin depend on the age or weight of the child, and were summarised earlier in Table 35.1. Look back at it now, and then answer the following question.

Suppose you saw a three-year-old girl with non-severe pneumonia. What dose of co-trimoxazole syrup would you give this child, and for how many days?

She is between 12 months and five years, so you should give her 7.5ml (one and a half teaspoons) of co-trimoxazole syrup (containing 80 mg trimethoprim + 400 mg sulphamethoxazole), twice a day for five days (look back at Table 35.1).

If any of your non-severe patients do not improve with the drug treatments you give them, or if their condition gets worse, immediately refer them to the nearest health centre or hospital.

Co-trimoxazole for HIV-positive children should be prescribed by doctors as prophylaxis against opportunistic infections with bacteria, viruses and fungi that cause pneumonia. Part 3 of this Module includes a detailed discussion of the prevention and treatment of pneumonia in people living with HIV infection.

If a one-month-old child comes to you with symptoms of fever and a respiration rate of 70 breaths per minute, what should you do?

The child is less than two months old and may have pneumonia, so it is at high risk of serious complications (e.g. meningitis and death). Therefore, refer the baby immediately to the nearest hospital or health centre.

35.5 Prevention and control of acute respiratory tract infections

Finally, we turn to the methods of prevention and control of acute respiratory tract infections (ARIs). You need to know about them so you can teach members of your community how they can protect their children and vulnerable adults from acute otitis media, pharyngitis and pneumonia.

Do you remember the difference between prevention and control?

Prevention measures, such as immunization, are applied before the occurrence of a communicable disease to reduce the risk that it will develop. Control measures, such as the treatment or isolation of cases, are applied after the occurrence of the disease, with the aim of reducing the transmission of the infectious agents to new susceptible people.

Prevention measures for ARIs include:

- Feeding children with adequate amounts of varied and nutritious food to keep their immune system strong.

- Breastfeeding infants exclusively (no other food or drinks, not even water) for the first six months (Figure 35.9); breastmilk has excellent nutritional value and it contains the mother’s antibodies which help to protect the infant from infection.

- Avoiding irritation of the respiratory tract by indoor air pollution, such as smoke from cooking fires; avoid the use of dried cow dung as fuel for indoor fires.

- Immunization of all children with the routine Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) vaccines in Ethiopia (Box 35.5).

Box 35.5 EPI vaccines that protect against acute respiratory tract infections

The dosages, schedules and vaccination routes for Hib, measles and pneumococcal vaccines are taught in the Immunization Module.

Immunize all children with:

- Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccine at 6, 10 and 14 weeks; Hib is one of the five vaccines in the pentavalent vaccine used in Ethiopia.

- Measles vaccine at nine months of age.

- Pneumococcal vaccine, when it becomes available in the EPI, to protect them against Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteria.

You can help to control the spread of respiratory bacteria by educating parents to avoid contact as much as possible between their children and patients who have ARIs. You should also teach people with ARIs to cough or sneeze away from others, hold a cloth to the nose and mouth to catch the airborne droplets when coughing or sneezing, and disinfect or burn the cloths afterwards. Immunization also increases control, by reducing the reservoir of infection in the community and increasing the level of herd immunity (described in Study Session 1 in Part 1 of this Module).

Summary of Study Session 35

In Study Session 35, you have learned that:

- Acute respiratory tract infections (ARIs) may affect the upper or lower respiratory tracts and are major public health problems in Ethiopia.

- Malnutrition, under-nutrition, lack of exclusive breastfeeding, lack of immunization, indoor air pollution and HIV infection are the major risk factors for ARIs.

- Acute otitis media is a common upper respiratory tract infection in young children, which is manifested by fever, ear pain, pus discharging from the ear and irritability. Children with symptoms of acute otitis media should be identified as soon as possible and treated by ‘wicking’ the pus from the ear, and giving antibiotics to prevent complications such as deafness,meningitis and pneumonia.

- Pharyngitis is another common upper respiratory tract infection, which is manifested by fever, sore throat and swollen inflamed tonsils. Children with symptoms of pharyngitis should be referred to a higher level health facility for assessment and treatment.

- Pneumonia is the major killer of children in Ethiopia and is among the top five causes of illness and death among adults.

- Severe pneumonia in children is manifested by the presence of danger signs, which include fast breathing, fever, chest in-drawing and stridor. Children with severe pneumonia are at high risk of death, and should immediately be referred to a higher level health facility to save their lives.

- Co-trimoxazole or amoxicillin are the antibiotics authorised at Health Post level to treat acute otitis media and non-severe pneumonia. Dosages are based on the patient’s age and weight.

- Prevention and control of acute respiratory tract infections include adequate nutrition, exclusive breastfeeding for infants under six months of age, immunization, protection from indoor smoke pollution, keeping children away from patients with pneumonia, teaching people to cough and sneeze away from other people, and co-trimoxazole prophylaxis for adults and children with HIV infection.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 35

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering the following questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 35.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 35.1 and 35.2)

Imagine that you see a 67-year-old man at a rural village with cough, fever and fast breathing. What is your diagnosis and what action should you take?

Answer

Fever, cough and fast breathing in old age can be indicators of severe pneumonia. Therefore, the man should be referred to a health centre or hospital immediately for further assessment and specialised treatment.

SAQ 35.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 35.1, 35.2, 35.3 and 35.4)

Which of the following statements is false? In each case, explain why it is incorrect.

A A 40-day-old infant who has fast breathing can be treated at home.

B Acute otitis media and pneumonia can be caused by the same bacteria.

C Rheumatic heart disease is the result of the heart becoming infected with bacteria.

D Bacterial pneumonia in children is usually more severe than viral pneumonia.

E Pharyngitis can be prevented by immunization.

Answer

A is false. A 40-day-old child with fast breathing should be immediately referred to a hospital or health centre for treatment. He may develop serious complications like pneumonia.

B is true. Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteria can cause acute otitis media and pneumonia.

C is false. Rheumatic heart disease is due to damage of the heart tissue by antibodies produced to attack Group A Streptococci. It is not caused by bacterial infection of the heart.

D is true. Bacterial pneumonia in children is usually more severe than viral pneumonia. The clinical manifestations of bacterial pneumonia include fever, cough, fast breathing, chest in-drawing and stridor. The clinical manifestations of viral pneumonia develop gradually and include fever, cough and wheezing.

E is false. There is not currently a vaccine available in Ethiopia to immunize against the Group A Streptococci that cause pharyngitis.

SAQ 35.3 (tests Learning Outcomes 35.1 and 35.3)

State at least three clinical signs that you might expect to find in a four-year-old child with severe pneumonia.

Answer

Chest in-drawing, stridor, respiration rate faster than 40 breaths per minute, and the presence of general danger signs such as being unable to eat or drink, lethargy or loss of consciousness, indicate a classification of severe pneumonia in a four-year-old child.

SAQ 35.4 (tests Learning Outcome 35.3)

Which one of the following is the preferred drug for treating acute otitis media or non-severe pneumonia in children at Health Post level?

- a.Arthemeter-lumefantrine

- b.Paracetamol

- c.Co-trimoxazole

- d.Quinine

- e.Amoxicillin

Answer

Co-trimoxazole (c) is the preferred drug for treating acute otitis media or non-severe pneumonia at Health Post level. If co-trimoxazole is not available, then (e) (amoxicillin) should be given.

SAQ 35.5 (tests Learning Outcomes 35.1, 35.2 and 35.4)

Complete Table 35.4 by placing a cross in the appropriate boxes to indicate whether each of the actions in the first column is a prevention or a control measure against ARIs – or both.

| Action | Is it prevention? | Is it control? |

|---|---|---|

| Early diagnosis and treatment | ||

| Adequate nutrition | ||

| Immunization against respiratory tract infections | ||

| Reduction of indoor smoke pollution | ||

| Coughing or sneezing into a cloth, or turning away from other people |

Answer

The completed version of Table 35.5 appears below.

| Action | Is it prevention? | Is it control? |

|---|---|---|

| Early diagnosis and treatment | X | |

| Adequate nutrition | X | |

| Immunization against respiratory tract infections | X | X |

| Reduction of indoor smoke pollution | X | |

| Coughing or sneezing into a cloth, or turning away from other people | X |