Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 26 April 2024, 9:17 AM

Nutrition Module: 12. Nutrition and HIV

Study Session 12 Nutrition and HIV

Introduction

Your work as a Health Extension Practitioner will often bring you into contact with people who have HIV. These people will be suffering from malnutrition and undernourishment. There is a close relationship between HIV, malnutrition and other infections. This is because HIV compromises nutritional status, and poor nutrition further weakens the immune system, increasing susceptibility to opportunistic infections.

People living with HIV/AIDS (PLHIV), especially children who also have a degree of malnutrition, are at high risk of opportunistic infections and early death. Even mild and moderate malnutrition increases the risk of death. Identifying and addressing malnutrition in people who have become HIV-infected can help them heal faster from infection, strengthen their immunity, and possibly slow the progression to AIDS. Depending on the degree of malnutrition, nutrition care can be given at home or at the out-patient or in-patient level. Thorough nutrition assessment is needed to manage nutrition problems effectively.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 12

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

12.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQs 12.1, 12.2, 12.3 and 12.4)

12.2 Explain the relationship between nutrition and HIV. (SAQ 12.1)

12.3 List the effects of good nutrition on HIV. (SAQ 12.2)

12.4 List the seven ways in which PLHIV are able to maintain their strength and health. (SAQ 12.2)

12.5 Describe feeding options for an infant born to an HIV-positive mother. (SAQ 12.3)

12.6 Explain the benefits and risks of each of the feeding options for an infant born to an HIV-positive mother. (SAQ 12.3)

12.7 Explain the strategies that can be used to decrease transmission of HIV to an infant after birth. (SAQ 12.4)

12.1 Nutrition and infection

Before learning in more detail about the relationship between nutrition and HIV it is important to understand the relationship between nutrition and infection in general. Poor nutrition increases the body’s vulnerability to infections, and infections in their turn make poor nutrition even worse. Inadequate dietary intake lowers immune system functioning and reduces the body’s ability to fight infections. Poor nutrition is therefore likely to increase the incidence, severity and length of infections. Symptoms that accompany infections such as loss of appetite, diarrhoea and fever lead to further reduced food intake, poor nutrient absorption, nutrient loss and altered metabolism. All of these contribute to weight loss and growth faltering, which in turn further weaken the immune system.

An adequate balanced diet, proper hygiene, food safety and nutritional management of symptoms are critical interventions to break the cycle of infection and malnutrition.

12.2 HIV and nutrition

HIV infection progressively destroys the immune system, leading to recurrent opportunist infections (OIs), debilitation and death. OIs are infections that take advantage of a weak immune system. Poor nutritional status is one of the major complications of HIV and a significant factor that might lead people to develop full-blown AIDS. In places where there are inadequate food supplies (resource-limited settings), many people who become infected with HIV may already be undernourished. Their weakened immune systems further increase their vulnerability to infection.

12.2.1 Poor nutrition and HIV: a vicious cycle

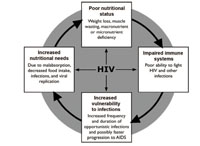

In this section you are going to look at the damaging cycle that can lead to a person with HIV and under-nutrition developing a variety of health problems including weakness, weight loss and loss of muscle tissue and fat. This cycle is represented in Figure 12.1. Vitamin and mineral deficiencies may occur at a time when a person actually has increased nutritional needs because of infections, viral replication and poor nutrient absorption. The whole body develops reduced immune functioning and increased susceptibility to opportunistic infections.

As you can see from Figure 12.1, the relationship between HIV and nutrition is multidirectional. HIV can cause or worsen undernutrition by making the person feel poorly and want to reduce their food intake at the same time as their body has increased energy requirements in an attempt to fight the infection. The disease itself may make the absorption of energy and other nutrients less efficient. Undernutrition in turn further weakens the immune system, increasing the risk of infection and worsening the disease’s impact. Box 12.1 summarises these points.

Box 12.1 The effects of under-nutrition on HIV

If a person living with HIV infection is under-nourished, they will have a weakened immune system that may lead to increased susceptibility to opportunistic infections. The person may also have a slow rate of healing from illnesses, possibly fast progression of the HIV disease state, and response to treatment may be poor.

12.2.2 Breaking the cycle of HIV and undernutrition

Improving and maintaining good nutrition may prolong health and delay the progression of HIV to AIDS. Because the impact of proper nutrition begins early in the course of HIV infection, even before other symptoms are observed, as a Health Extension Practitioner you will have an opportunity to make a real impact on the lives of people living with HIV (PLHIV).

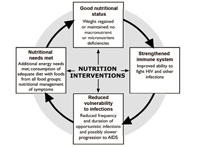

Nutrition care and support helps PLHIV maintain and improve their nutritional status, improve their immune response, manage the frequency and severity of symptoms, and improve their response to antiretroviral therapy (ART) and other medical treatment. Figure 12.2 illustrates how the cycle between HIV and malnutrition can be broken using different interventions.

Have a close look at Figure 12.2. Can you tell from this figure how the vicious cycle between HIV and poor nutrition can be reversed?

Figure 12.2 illustrates how effective nutrition interventions such as an increased and varied diet with food from different food groups, can help transform the cycle of HIV and undernutrition into a positive relationship between improved nutritional status and stronger immune response, which will reduce vulnerability to infections.

12.2.3 The effects of HIV on nutrition

People living with HIV infection have a higher chance of developing undernutrition than those who are not infected. HIV affects the nutritional status of these people in different ways. The effects of HIV may occur at different times during the course of their illness.

The following are typical adverse effects of HIV infection which may affect the person’s nutritional status:

- Reducing food consumption because of appetite loss or anorexia

- Nausea

- Oral thrush

- Constipation

- Bloating or heartburn.

People with HIV also tend to have various oral conditions that can make it difficult for them to eat. Impact on nutritional status includes:

- Impaired nutrient absorption

- Increased energy needs because of fever

- Possible increase in the need for other nutrients because of symptoms such as anaemia

- HIV-associated wasting

- Changing body composition.

12.3 Nutritional care of people living with HIV

As a Health Extension Worker, you are expected to give care to PLHIV. Nutritional care is one of the most important ways that you can look after someone who has an HIV infection and help them to maintain their health. You will be able to give nutritional care both at health post level and during home-based care. You learned the procedures for assessing the nutritional status of PLHIV in Study Session 5 and how to manage the nutritional problems you identified in Study Session 9. You are now going to learn about the types of care that you can provide to a PLHIV.

12.3.1 Nutritional care of HIV-positive adults and adolescents

Your work in the community will almost certainly bring you into contact with people living with HIV. This gives you the opportunity to help them maintain their health for as long as possible. For this reason you should make sure that they are weighed on a regular basis. You may have to speak to them in detail about the need for them to attend for weighing on a regular basis; you can explain that it will enable you to monitor their health and provide them with good advice.

Why do you think it is important for people living with HIV to be weighed periodically?

It is important to weigh people regularly because weight loss is a sign of disease progression. If you see that a person is losing weight, you can suggest ways of increasing their nutrition intake so they do not have nutrition deficiencies which can lead to a weak immune system.

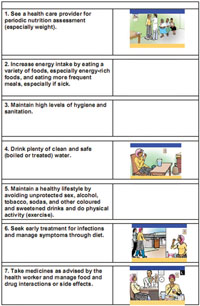

Look carefully at the series of pictures in Figure 12.3. These show seven ways that you could recommend to PLHIV how to maintain their strength.

In addition to these seven activities, people living with HIV might require micronutrient supplementation. Sometimes the use of traditional therapies to boost nutrition and maintain strength is also really important.

How would you encourage PLHIV to adopt these seven activities?

You could talk to them about the importance of eating enough healthy food to ensure their immune system stays as strong as possible, so they are not vulnerable to infection and can try to slow the progression to AIDS.

What diet would you recommend to someone in your community who is living with HIV?

The best and recommended source of good nutrition is a variety of foods, including fruits and vegetables, grains, and animal products.

12.3.2 Nutritional care of HIV-positive pregnant and lactating women

Most infants who are exclusively breastfed by HIV-positive mothers do not become infected with HIV.

A woman’s nutritional status during pregnancy influences the risk of maternal to child transmission of HIV (MTCT) as well as their pregnancy outcomes (see Figure 12.4). A mother can transmit HIV to her infant during pregnancy and delivery or through breastfeeding, but most infants of HIV-positive mothers do not become infected. In deliveries where no interventions are used to reduce transmission, about 5-10% of infants are infected during pregnancy, 10-20% during labour and delivery, and 5-20% during breastfeeding if the child is breastfed.

Working in the community you should have the opportunity to look after women who have HIV during their pregnancies. In order to give them and their new babies optimal care you should follow the same procedure you learnt in Study Session 5 for assessing the nutritional status of HIV-positive pregnant and lactating women. You should also counsel them on the seven ways to maintain their strength that you have just learnt about.

You will be able to stress to the women the importance of them attending ANC services, delivering in a health facility, and follow-up care to reduce the possibility of transmitting HIV to their babies.

12.4 Feeding babies and children born from women who are HIV-positive

Appropriate feeding practices are essential for optimal growth, development and the survival of infants and children. Breastfeeding plays a key role in optimally supplying all the nutrients and energy needs of infants in the first six months of life. Between six and twelve, breastmilk contributes to 50% of the infant’s energy requirement and remains an important source of vitamins and minerals. On the other hand for up to 40% of babies with HIV, the infection came from postnatal transmission of HIV through breastfeeding. However in resource constrained countries, replacement feeding actually causes equal or more infant deaths due to malnutrition and infection when compared to the number of deaths due to HIV as a result of postnatal transmission through breastfeeding.

Understanding the relationship of breastfeeding and child survival is a key to successful counselling of HIV positive mothers on how to optimally feed their babies. This section addresses important issues with regard to infant feeding in the context of HIV in Ethiopia. The IMNCI Module also looks at how to assess and support children living with HIV/AIDS.

12.4.1 Breastfeeding and HIV

Breastfeeding accounts for 30–40% of mother to child transmission in populations where breastfeeding is practised until the child is two years of age. However, replacement feeding, if not carried out properly, is associated with increased risk of morbidity and mortality at a young age. This is particularly the case in low-resource settings.

Exclusive breastfeeding during the first six months of life is associated with lower transmission of HIV and improved child survival compared to non-exclusive breastfeeding children in developing countries.

There are a number of common terms used to describe infant feeding practices. You may already be familiar with these terms. Box 12.2 summarises what each one means.

Box 12.2 Common terms used in infant feeding options

- Exclusive breastfeeding: Giving only breastmilk and no other drinks or foods, not even water, with the exception of drops or syrups consisting of vitamins, mineral supplements or medicine.

- Exclusive replacement feeding: The use of breastmilk substitute totally avoiding breastmilk.

- Mixed feeding: Giving breastmilk with non-human milk and solids and other fluids.

- Complementary feeding: Addition of semi-solid or solid food in addition to breastmilk or formula at six months.

Mothers who are able to give exclusive replacement feeding can usually do this successfully if a number of factors are in place. These are known as the AFASS factors, and we have summarised these in Box 12.3.

Box 12.3 AFASS components

Acceptable: The mother has no barrier in choosing a feeding option for cultural or social reasons, or for fear of stigma and discrimination

Feasible: The mother (or family) has adequate time, knowledge, skills, and other resources to prepare feeds and to feed her infant, and the support to cope with any family, community and social pressure

Affordable: The mother and family, with available community and/or health system support, can pay for the costs of the feeding option, including all ingredients, fuel and clean water, without compromising the family’s health and nutrition spending. The current estimate for formula (without including fuel, water, mother’s time, etc.) for a child on exclusive replacement feeding is about 1200 to 1500 Eth. Birr per month

Sustainable: The mother has access to the continuous and uninterrupted supply of all ingredients and commodities needed to implement the feeding option safely for as long as the infant needs it.

Safe: Replacement foods are correctly and hygienically prepared and stored in nutritionally adequate quantities; infants are fed with clean hands using clean cups.

Why do you think that exclusive replacement feeding might be difficult for some mothers in your community?

Exclusive replacement feeding is difficult, especially in rural situations because it is expensive for families on low incomes and because preparing formula milk in consistently hygienic conditions is almost impossible.

12.4.2 Counselling mothers who are HIV-positive

One of the routes of HIV transmission from mother to child is through breastfeeding. Therefore it’s very important to counsel a mother who is HIV-positive on feeding options to her infant (see Figure 12.5). In this section we will discuss how you can help mothers decide the preferred feeding options for her child.

If an HIV-positive mother comes to you for counselling on how to feed her infant, how will you counsel her? Exclusive breastfeeding? Exclusive replacement feeding? Or mixed feeding? You may have to help her choose between two ‘evils’. It’s a difficult choice. First, as you have learnt, breastmilk is very important for the survival of the child. The difficult thing in recommending continuing breastfeeding is that HIV infection is present in breastmilk. So when you advise the mother to continue with exclusive breastfeeding, she needs to know she is possibly exposing the child to HIV infection.

If, on the other hand, you advise the mother on exclusive replacement feeding, the positive thing is that there will be no exposure of the child to the HIV virus. So the child will probably remain HIV-free. The difficult thing with this option is that not giving a child breastmilk, but relying on infant formula, is associated with a high rate of morbidity and mortality. The high risk of malnutrition and diarrhoeal diseases are very common in children who are not breastfed, especially in resource-limited countries.

12.4.3 Possible feeding options for an infant born to an HIV-positive mother

For you to be able to advise an HIV-positive mother you need to be able to advise them of the risks involved in each feeding option, and explain why exclusive breastfeeding for six months is the recommended option in Ethiopia.

Mixed feeding

Studies have shown that mixed feeding carries both a risk of HIV transmission from mother to child and a high risk of malnutrition. Therefore you must counsel parents to avoid mixed feeding and continue either with exclusive breastfeeding or exclusive replacement feeding.

Exclusive replacement feeding

The use of exclusive replacement feeding (using commercial infant formula) eliminates the transmission of HIV from breastfeeding. Exclusive replacement feeding means that the mother completely avoids breastfeeding her baby. However, as you read earlier, there are risks as well as benefits associated with exclusive replacement feeding. These are set out in Box 12.4.

Box 12.4 Exclusive replacement feeding

Risks

- Increased risk of serious diarrhoeal infections and malnutrition leading to higher rates of early death

- Inadequate supply of formula leading to mixed feeding, increasing the risk of MTCT

- Formula feed is often diluted, improperly mixed, given inconsistently or prepared with unclean water

- There is an absence of protective factors in formula.

Benefits

- Less likelihood of HIV transmission from mother to child if entirely exclusive replacement feeding.

Because of the difficulties of exclusive replacement feeding, avoidance of breastfeeding is not safe in countries with limited resources like Ethiopia.

Exclusive breastfeeding

Several studies have demonstrated that babies who are exclusively breastfed are at a lower risk of acquiring HIV infection compared with infants who have mixed feeding. However, there are risks associated with exclusive breastfeeding.

HIV is present in the breastmilk of infected mothers and can be transmitted to infants by breastfeeding. This poses a substantial risk for acquisition of HIV infection for the infant. Women with advanced disease are at highest risk of transmitting the virus to their babies during breastfeeding. Prolonged breastfeeding (e.g. up to the age of 24 months) can increase the overall risk of mother-to-child transmission.

12.5 National feeding recommendations for an infant born to an HIV-positive mother

There is a growing body of evidence with regard to infant feeding choices in the context of HIV and the impact on HIV-free child survival. For this reason, and following the technical review by the national paediatric HIV/AIDS care and the treatment technical working group, the FMOH has made recommendations with regard to infant feeding and HIV. It’s important that as a Health Extension Practitioner, you are aware of these recommendations, which are set out below.

12.5.1 Infant feeding during the first six months of life

- The first and preferred infant feeding option in Ethiopia is exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life (see Figure 12.9). Stopping breastfeeding earlier than this should be avoided since this is associated with increased risk of death from diarrheal illnesses, malnutrition and pneumonia.

- Exclusive replacement feeding (formula feeding) is the second possible option for a minority of mothers. If this is the option chosen by a mother you have to make every effort to ensure that she does this safely. Some mothers may choose this option first but because of economic problems or cultural influences, they may end up mixing the formula with breastmilk, which will increase the risk of transmission.

As a Health Extension Practitioner you should try to support mothers to decide on the first option. If this is not chosen, you should do your best to ensure safety before you agree with a mother that she uses the exclusive replacement feeding option. Only very few mothers could make it safe.

If a mother is using replacement feeding, infant formula is preferred for the first six months of life. Home-modified animal milk if used should be a temporary measure, and given for short periods only.

12.5.2 Feeding infants and children from six–24 months of age

At six months of age all infants need complementary food in order to sustain normal growth and development. Appropriate complementary foods should be introduced at six months of age with continued breastfeeding. Breastfeeding should stop only when a nutritionally adequate diet without breastmilk can be provided. This is usually around 12 to 18 months of age.

12.6 Strategies to decrease transmission of HIV during breastfeeding

Infants who are confirmed to be HIV-infected should continue to breastfeed according to recommendations for the general population.

You have learned that the preferred infant feeding option in the context of maternal HIV is to support mothers to breastfeed exclusively for the first six months. Every effort should be made to decrease the chance of transmission of HIV from the mother to the child.

The following list shows some of the strategies that may help to decrease the possibility of transmission:

- Expand ANC services and universal access to antenatal prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMCT) services

- Actively support exclusive breastfeeding from birth until six months

- Advise parents not to mix feeds, advise them never offer other liquids, milks or foods in addition to breastmilk in the first six months, as this irritates the baby’s gut and may lead to a higher rate of virus transmission to the infant

- Promote good health and nutrition of the mother

- Advise mothers to maintain good breast health and seek immediate attention for cracked nipples, mastitis or abscesses

- Support mothers to avoid becoming infected with HIV during breastfeeding (counsel on safe sex)

- Promote and support the initiation of complementary feeding at six months and to continue breastfeeding until the child is 12–18 months.

As a Health Extension Practitioner you have an important role in these strategies. You can use your knowledge and your skills in counselling to advise mothers (and families) on the best feeding options for infants born to HIV-positive mothers in order to optimise the health and development of the infant.

Summary of Study Session 12

In Study Session 12 you have learned that

- If a patient with HIV infection is under-nourished they will have a weakened immune system that may lead to increased susceptibility to opportunistic illnesses, and slow the rate of healing from illnesses.

- A weak immune system can hasten the progression of HIV and may impact on a patient’s ability to respond to treatment.

- Improving and maintaining good nutrition may prolong health and delay the progression of HIV to AIDS. The impact of proper nutrition begins early in the course of HIV infection, even before other symptoms are observed.

- The preferred infant feeding option in Ethiopia is exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life. Stopping of breastfeeding earlier than this should be avoided since this is associated with increased risk of death from diarrhoeal illnesses, malnutrition and pneumonia.

- Exclusive replacement feeding has a lower chance of MTCT of HIV, but in resource limited countries like Ethiopia, the cost of the formula is high and preparing it safely and consistently is very difficult. Poorly prepared and diluted milk stands a high chance of leading to infections and malnutrition.

- Mixed feeding (giving both breastmilk and formula) to an infant born to an HIV positive mother increases the chance of MTCT and should be avoided.

- Infants who are confirmed to be HIV-infected should continue to breastfeed according to Ethiopian recommendations.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) For Study Session 12

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this module.

SAQ 12.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 12.1 and 12.2)

What do you think are the main effects of HIV on nutritional status?

Answer

Nutritional status and the progression of HIV are strongly interrelated. HIV infection increases the body’s energy needs while it diminishes appetite and decreases the body’s ability to digest food and absorb nutrients. This leads to malnutrition which in turn accelerates the HIV infection.

SAQ 12.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 12.1, 12.3 and 12.4)

- a.Discuss the most important effects of good nutrition to PLHIV.

- b.What advice would you give to a PLHIV so they can maintain their health and strength for as long as possible?

Answer

- a.Nutrition care and support helps break the vicious cycle of HIV and malnutrition by helping people living with HIV (PLHIV) maintain and improve their nutritional status, improve their immune response, manage the frequency and severity of symptoms, and improve their response to antiretroviral therapy (ART) and other medical treatment.

- b.There are seven strategies you could advise PLHIV to adopt to increase their chances of being healthy and strong. These include maintaining a healthy life style, eating energy-rich foods, drinking clean water, having regular health checks for weight and taking appropriate medicines. As a Health Extension Practitioner you can encourage PLHIV in your community to seek early treatment for symptoms and advise them on how they can manage these through diet and maintaining high levels of hygiene and sanitation.

SAQ 12.3 (tests Learning Outcomes 12.1, 12.5 and 12.6)

- a.What is the recommended infant feeding option to an infant born to an HIV-positive mother?

- b.What is the reason that this option is preferred?

Answer

- a.The preferred recommended infant feeding option to an infant born to HIV-positive mother is exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life. Appropriate complementary foods should be introduced at six months of age with continued breastfeeding. Breastfeeding should stop only when a nutritionally adequate diet without breastmilk can be provided. This is usually around 12 to 18 months of age.

- b.The majority of the mothers in your communities can’t fulfil the AFASS criteria and children who are not breastfed are at high risk of developing malnutrition and numerous childhood infections. Therefore the survival of the infant will be significantly affected.

SAQ 12.4 (tests Learning Outcomes 12.1 and 12.7)

Discuss the important measures that you could adopt in your community to decrease MTCT of HIV for an infant who is breastfeeding and who has been born to an HIV-positive mother.

Answer

As a Health Extension Practitioner, you may be able to perform the following measures to help decrease MTCT of HIV for an infant who is breastfeeding and who has been born to an HIV-positive mother:

- Screen HIV-positive mothers for ART eligibility (see the Communicable Disease Module)

- Provide an effective ARV prophylactic regimen for non-eligible women and their infants

- Actively support exclusive breastfeeding from birth until six months

- Advise mothers not to mix feed because this increases the risk of MTCT

- Advise mothers how to maintain good breast health and seek immediate attention for cracked nipples, mastitis or abscesses

- Promote and support the initiation of complementary feeding at six months and recommend continuing breastfeeding until 12 – 18 months

- Support mothers to avoid becoming infected with HIV during breastfeeding (counsel on safe sex).