Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 19 April 2024, 9:52 AM

TI-AIE: Promoting reading for pleasure

What this unit is about

Encouraging students to enjoy reading is beneficial to them because it can stimulate and excite their imagination and curiosity. There is a wealth of literature available in English and being able to read in English allows your students to access this. Reading in English can teach your students new skills and ideas, and bring them to understand more about the world and different cultures.

When students read in English, they see examples of words and grammatical structures being used in many different ways. This helps them to improve their own vocabulary and grammar use. The more students read, the better they become at reading in any language: ‘reading is a transferable skill. Improving it in one language improves it in others’ (National Curriculum Framework, 2005, p. 39). However, many students don’t enjoy reading in English, and they don’t read much English beyond the passages in the textbooks or supplementary readers.

This unit describes how you can design classroom activities that create opportunities for students to engage in more sustained reading in English using both the supplementary reader and other texts.

What you can learn in this unit

- Classroom activities to create opportunities for students to read longer passages in English.

- Ways to encourage students to read in English beyond the classroom.

1 Stimulating students’ interest in reading longer passages in English

Students at secondary level are expected to read many long passages in English, for example plays or passages in the supplementary reader. These are some of the plays and passages from NCERT textbooks for Classes IX and X:

- The Happy Prince: This is a fairy tale written by the Irish writer Oscar Wilde and published in 1888. The ‘happy prince’ in the story is a statue decorated with gold leaves and precious stones. The prince looks out over a city where many people are suffering. He asks a swallow to take his gold and jewels to help the poor. The swallow agrees, but dies from the cold while doing so. This breaks the prince’s heart. An angel takes the swallow and the prince’s heart to paradise to meet God. (This fairy tale is available in the NCERT textbook Moments: Supplementary Reader in English for Class IX.)

- The Accidental Tourist: This is an extract from a book by the contemporary American writer, Bill Bryson. The author describes his experiences as a traveller. He writes about humorous things that have happened to him on aeroplanes, such as knocking a drink over the person sitting next to him, or dropping the contents of his bag. (This extract is available in the NCERT textbookMoments: Supplementary Reader in English for Class IX.)

- The Proposal: This is a play written by the Russian writer Anton Chekhov in 1888–9. Ivan Lomov, a wealthy neighbour of Stephan Chubukov, comes to propose to Stephan’s daughter, Natalya. At the meeting, Ivan and Natalya quarrel about everything and almost forget about the proposal. Natalya agrees to marry, and the quarrelling continues. (This play script is available in the NCERT textbook First Flight: Textbook in English for Class X.)

- The Hack Driver: This is a short story written by the American writer Sinclair Lewis in 1923. It is about a young lawyer who is looking for a witness in a law case, a man named Oliver Lutkins. He hires a driver and they look all over the town for Lutkins, but can’t find him. In the end, the lawyer discovers that the driver is in fact Lutkins, the man he is looking for. (This story is available in the NCERT textbook Footprints without Feet: Supplementary Reader in English for Class X.)

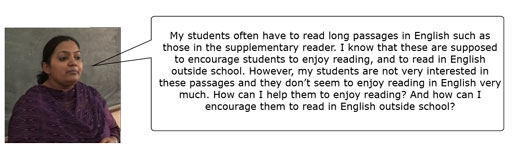

Pause for thought Here are some questions for you to think about after trying this activity. If possible, discuss these questions with a colleague.

|

Some students will enjoy reading any kind of literary text, but some of these stories and plays may not initially appeal to some students. In some cases even the title (for example, The Hack Driver) may not be understood by students, so they may not feel motivated to read it. A table showing how the texts listed above relate to students’ lives is provided in Resource 1.

Read Case Study 1 to find out how one teacher created a meaningful activity to relate his students’ experiences to the theme of a play in the supplementary reader.

Case Study 1: Komala’s teacher helps Class X to feel more motivated to read a play

Komala is a Class X student. Her teacher recently helped the class to feel more motivated to read The Proposal, a play by the Russian writer, Anton Chekhov.

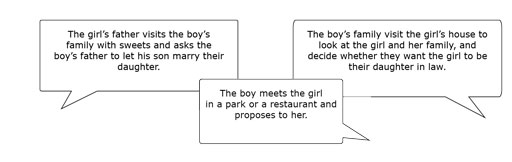

There was a play at the end of our English textbook. I have to say that I wasn’t looking forward to it very much – it looked very long, and I had no idea what it was about. Before we read the play in class, however, our teacher asked us to think about the last time we attended a wedding. I thought about my cousin’s wedding last December. The teacher asked us about the some of the traditions around how marriage proposals are usually made. A few students gave answers:

Our teacher then asked us if we had ever seen any marriage proposal scenes in films. I couldn’t think of any, but Sikta raised her hand and gave the name of a film: Vivah. Fulki thought of another: Yeh Jawaani Hai Deewani. Soon students were saying more, and then I thought of one: Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge. That’s one of my favourite films.

After this, our teacher wrote the words ‘The Proposal’ on the blackboard, and asked us if we knew what it meant. We guessed what it meant after our previous discussion. Then our teacher organised us into groups of three. My group had my friend Deepa and another girl, Tanushri. The teacher asked us to imagine a traditional proposal scene in a film, and to think of the people who would be in the scene. He told us to invent names for the characters, and to describe them briefly in English. We wrote the following:

Vinod: The bridegroom. He is a 26-year-old electrical engineer working in a big company in Mumbai.

Raveena: The bride. She is 22 years old and has just finished her graduation in English.

Mr Ashok Nath: Vinod’s grandfather, and the head of the family.

Mr Alok Nath: Vinod’s father, who is a senior government officer.

Mrs Meera Nath: Vinod’s mother, who is a school teacher.

Dr Ramesh Kumar: Raveena’s father, who is a well-known heart specialist.

Mrs Shanti Kumar: Raveena’s mother, who is a housewife.

Then he told us to write a few lines for the scene in English, as if we were writing that part of the film. Deepa, Tanushri and I wrote a scene for two characters: the bride’s father, Dr Ramesh Kumar, and the bridegroom’s grandfather, Mr Ashok Nath. It was a little difficult to write their lines in English, but Tanushri was very good at English and she helped us. We didn’t know the English word for ‘horoscope’ so we raised our hands and asked the teacher, and he told us. This is what we wrote:

Ramesh Kumar: Namaskar, Ashok Ji! How are you? We heard you have just recovered from viral fever. Are you all right now? You have to be – we need your blessings always!

Ashok Nath: Namaskar, Dr Sahab. My blessings – may you live a long life! What brings you to our house?

Ramesh Kumar: As you know, Ashok Ji, our Raveena has completed her graduation, and we would like to find her a groom.

Ashok Nath: Of course! You have a very intelligent daughter – she will get a good boy!

Ramesh Kumar: That is why we are here today. We would like to offer our Raveena as a bride for your grandson Vinod.

Ashok Nath: Hmm … if the boy and the girl are willing, I have no objection! But we will have to match their horoscopes.

When we were ready, our teacher asked two groups to perform some of the proposal scenes. It was funny to watch them. Preeti played the role of the old man Ashok sahib and she made me laugh!

After that, the teacher told us that we were going to read a play called The Proposal. It was about another marriage proposal, but this one was set in Russia many years ago. He asked us what we thought that marriage proposal might be like back then – we had no idea. He told us to look quickly at the play in our textbook, and to see which characters were involved. There were three: a young woman, her father and a man who wanted to marry the woman. I wanted to see if they said anything like what we had written in our scene and if marriage traditions in Russia were different to those in India.

Pause for thought How did Komala’s teacher create a motivating activity around the Russian play? |

In Case Study 1, the teacher asked his students to think about scenes of marriage proposals that they had seen in films, and to write a simple scene in English. This prepared the students for reading The Proposal, and the kind of language that they might find in it. (See the unit Supporting reading for understanding for more about preparing students for a text.) It also helps to relate the play – which is set in Russia in the late nineteenth century – to the experiences and interests of the students.

This idea can be used with any kind of text that your students need to study. You may not be familiar with the writer or the passage. If not, try to find out as much as you can before you teach it (for example, by asking a colleague or finding information on the internet, if you can access it).

Activity 1: Preparing students for reading in English

Choose a text you are going to use in class in the next week. Think about how you will introduce it to your students.

These questions will help you think about how you might relate the text to your students’ lives:

- Who wrote the passage? Are students familiar with the writer?

- What is the passage about? Is it about topics that are familiar to your students? Is it set in another (unfamiliar) place?

- When was the passage written? Are the ideas, values and words used different to those that your students know?

Now plan and teach an activity to introduce your students to the text. You might use drama, role play or a discussion, or relate it to a modern TV drama or song. See Resource 2, ‘Using role play and drama’, for more ideas on how to do this.

Pause for thought Here are some questions for you to think about after trying this activity. If possible, discuss these questions with a colleague.

|

2 Helping students to maintain interest in reading a longer text

It is possible for you to motivate students to begin reading a text by relating it to their own lives and experiences. However, it can be difficult to maintain that interest, especially when the text is long. Here are some ideas suggested by other teachers to help students to stay interested in reading longer passages in English.

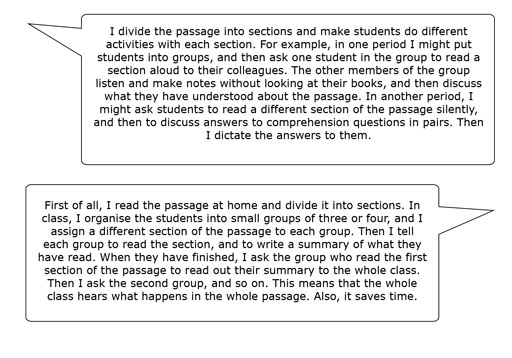

Dividing passages up and using a variety of activities with each section makes them more interesting to your students. You may worry that your students are not able to do this because they can’t read independently, or that they won’t understand every word of the passages. It is true that they may not understand every word they read, but they will usually get a general understanding of the passage – the most important events and the key points of the story. Reading to understand will help them to enjoy the passage, which in turn will help them to become better readers (see the units Supporting reading for understanding and Whole-class reading routines). You can read how one teacher used this technique in Case Study 2 and then try this yourself in Activity 2.

Case Study 2: Mr Sinha teaches The Happy Prince to Class IX

Mr Sinha teaches English to Class IX. He had to teach the story The Happy Prince from the supplementary reader. Here he describes what he did with the second section of the story (see Resource 3).

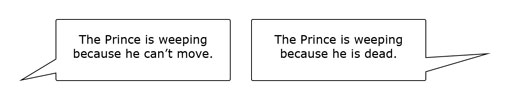

My students did the first section of the story in a previous class. That section ended with a question from the sparrow in the story: Why are you weeping then?

I reminded students of the question, and asked them to guess why the Prince was weeping. One or two of the students made some suggestions:

I told the class to listen and to find out why the Prince was weeping. I then read some lines from the passage aloud [NCERT, 2006a]:

‘Why are you weeping then?’ asked the swallow. ‘You have quite drenched me.’

‘When I was alive and had a human heart,’ answered the statue, ‘I did not know what tears were, for I lived in the Palace, where sorrow is not allowed to enter. My courtiers called me the Happy Prince, and happy indeed I was. So I lived, and so I died. And now that I am dead they have set me up here so high that I can see the ugliness and all the misery of my city, and though my heart is made of lead yet I cannot choose but weep.’

‘What! Is he not solid gold?’ said the swallow to himself. He was too polite to make any personal remarks.

I read the passage again, and told the class to discuss with their classmates why the Prince was weeping. Some of the students understood that he was weeping because he could see the ‘ugliness and misery’ of the city. Then I organised the class into groups of three students. With 53 students, that made 17 groups and one pair. I gave the groups that were sitting on one side of the room the section from The Happy Prince about the tale of the seamstress (from ‘Far away …’ to ‘Thinking always made him sleepy.’)

I assigned the groups that were sitting on the other side of the room the tale of the writer in the garret (from ‘When day broke …’ to ‘… and he looked quite happy.’)

I told the students to read their sections silently, and then to work in groups to write a short summary in their home language. I gave my class 30 minutes to read the section and to write the summaries. As they read and wrote their summaries I walked around the room, checking that students knew what they had to do, and answering questions about the passages. For example, one student asked me what the phrase ‘withered violets’ meant.

When they were ready, I asked a group from each side of the room to read out their summaries, so that the whole class heard a summary from each of the two sections. I asked them to say what the differences were between the tales – for example, in one the swallow helped a seamstress, and in the other a writer; in one tale the swallow took a ruby, in the other a sapphire.

By the end of the class, the students knew what had happened in a long section of the story, even though they had not read all of it. In fact, it wasn’t really important for them to read every single word together – and the students who want to can read both sections at home if they like.

Activity 2: Planning to teach a longer text over a number of classes

Find a longer passage from the textbook or supplementary reader that you will soon teach. Read the passage and divide it into a suitable number of sections (such as four). Remember that each section is for one lesson.

Plan a different activity that your students can do with each section that allows them to use each of the four skills: reading, writing, listening and speaking. This list below has some ideas. Try to use a variety of ways of working – for example, some activities could be with the whole class, while others could be in groups or pairs. You should always be clear why you are using particular approaches.

- Listening: Read the section aloud as students listen with their books closed. They should be told to listen out for information or answers to questions.

- Listening: Students read or listen to the sections and draw a picture or cartoon representing the scene or what happens.

- Reading: Ask students to read a section silently (perhaps with a time limit). They should then be asked to look for information or answers to questions

- Reading/listening and writing: Students read or listen to the section and take notes. They should then use their notes to write a summary or reconstruct the text

- Reading/listening, writing and speaking: Students read or listen to the sections and write summaries in English. They should then present these summaries to the class.

- Reading/listening and writing/speaking: Students read or listen to the sections and work in pairs or groups to answer comprehension questions.

Record your ideas using a form like Table 1. You can find one that has been completed in Resource 4.

| Class | ||

|---|---|---|

| Passage | ||

| Section | Activity | |

Pause for thought Here are some questions for you to think about after trying this activity. If possible, discuss these questions with a colleague.

|

Once you have tried a plan like this, make a note of what has worked and make another plan with another passage from the textbook or supplementary reader. See what works to improve your students’ learning.

3 Encouraging students to read in English beyond the classroom

Pause for thought Try to answer these questions about your students. If you are not sure, ask your students.

|

Many students don’t read much in English beyond the textbook and the supplementary reader. They may read more in other languages, and they may enjoy reading all kinds of different texts in books, magazines or newspapers, such as articles about films and sport; informative and factual texts; comics and magazines; jokes and cartoons. A few students may have access to the internet – or perhaps will have access in the future – and may read all kinds of texts in English online.

If it is possible, you can bring these kinds of texts into the English class. You could also invite your students to select their own favourite texts to bring into class. For example, if your students enjoy cartoons, they may be able to find cartoons in an English newspaper. When students can select what they read for themselves, they are more likely to enjoy the experience (see the unit Using resources beyond the textbook).

School libraries can be a good resource if you have one. The position paper written by the National Focus Group on Teaching of English (NCERT, 2006, section 1.2.2) states that students in schools with class libraries ‘read better than those in schools where reading is restricted to monotonous texts and frequent routine tests of spelling lists’. If you don’t have a library, perhaps you can create one yourself. If possible, buy some cheap books and set up a class library. Again, if it is possible, exchange books with teachers from neighbouring schools, and encourage parents to contribute where possible. If English books are not available in your town or village, perhaps friends and colleagues who travel might be able to buy some for you.

If you or your students have access to the internet, you can find many English texts to read. You can also find resources related to many of the poems, stories, plays and writers that feature in textbooks and supplementary readers, for example audio recordings of poems and videos. You can find links to some useful online resources in Resource 6.

Activity 3: Extending students’ reading in English

Here are some activities that encourage students to read in English beyond the classroom. Select one and try it with your students. After the activity, consider how it went; did all your students participate? Did you need to intervene at any point in the activity? If so, why? How did you assess their learning in this activity?

- A reading logbook: Students keep a diary of anything that they have read in English, including lessons from the textbook and passages from the supplementary reader. They should complete a page for each text, with information such as the name of the text, the writer, things theydid or didn’t like about the text, the character they liked best (where relevant), and so on. Encourage them to write down their thoughts and feelings about the text. They can do this in English or their home language. You could set aside one or two classes at the end of each month to discuss and share the logbooks.

- Class competitions: Introduce regular competitions related to reading. This could be drawing a picture based on a text, telling a story, reciting a poem or writing a story or a poem. Display examples of students’ work.

- Drama: Organise a class play. Ask the students to select or write a play (which you can help with). Students can select actors, write dialogues, make props, direct scenes and so on. Then they can perform their plays for students and teachers at the school. Parents could also be invited.

- Inviting a guest: If possible, invite a writer from the local area to talk about writing and the benefits of reading. It doesn’t matter if the writer writes in your home language. The benefits of reading are relevant in any language.

- A ‘Reading in English’ day: Hold a ‘Reading in English’ day with students from another class, or even from another school. Prepare different activities around reading texts from the syllabus or others. These might be reading a text or parts of a text aloud, quizzes about text, or transforming a prose text into a play, a play into a story, a story into a poem, a poem into a letter and so on. Prizes can be awarded.

Events, visits, competitions and prizes can take time and effort to organise. Perhaps you can organise them with other teachers, and colleagues from neighbouring schools. Remember that students will feel motivated by such activities, and that they will encourage to them to think positively about their English classes and learning English.

4 Summary

Many of the passages in textbooks and supplementary readers are written by unfamiliar authors, many years ago. It can be difficult for students to relate to the stories and characters in these texts. You can help students become more interested in reading such passages by making connections between the writers and their concepts and the students’ lives and experiences. You can help them to maintain that interest by dividing the passage into sections and planning different activities for each section. These activities focus on a general understanding of the passage and also give students opportunities to practise various English language skills (such as listening and writing).

You can further encourage an interest in reading by organising activities for the class or school such as competitions, visits and events.

These techniques will help your students to enjoy reading in English more. When students read more, their English improves, they learn more about the world and its people, and they enjoy reading more in any language. You can read more about encouraging reading and using literature in the classroom in this unit’s additional resources section.

Resources

Resource 1: Relating passages to students’ lives

| Passage | Potential reasons why students may not feel motivated | Ways of relating this passage to students’ lives |

|---|---|---|

| The Happy Prince: A fairy tale written by the Irish writer Oscar Wilde and published in 1888 | The writer Oscar Wilde may be unfamiliar Christian values may be difficult to understand for non-Christian students The fairy story may seem ‘old-fashioned’ Students may not know what a swallow is, or their migratory habits Students may not understand the lives of kings and princes, at least, not those from other countries |

Inform students about the author Connect Christian values to other religious values Connect the idea of fairy tales to Indian folk tales Discuss the migration of Indian birds Discuss the comforts rich people have, and compare that to being poor Discuss someone who is known to have sacrificed their lives to help the poor and needy Discuss what is needed to be happy – riches, kindness etc. |

| The Accidental Tourist: An extract from a book by contemporary American writer, Bill Bryson | The story assumes that readers travel a lot, and are familiar with flying by air Students may not understand concepts such as ‘frequent flyer miles’ Students may not see the humour very easily |

Discuss journeys that students have made (on train) Explain the procedures of travelling by air Teach vocabulary related to air travel Discuss how people behave with co-passengers on a journey |

| The Proposal: A play written by the Russian writer Anton Chekhov in 1888–9 | The writer Anton Chekov may be unfamiliar The play mocks the traditions of marriage in 19th century Russia – students are unlikely to be familiar with these traditions Students may not understand much about tensions relating to getting married |

Discuss great dramatists of India and inform the students about the author Compare marriage traditions of Russia with India Compare past and present wedding customs Discuss dowry and other customs related to the giving of gifts in marriage. |

| The Hack Driver: A short story written by American writer Sinclair Lewis in 1923 | The title is difficult to understand Legal vocabulary and concepts may be difficult to understand Students may not be familiar with American towns and their way of life in the 1920s |

Connect to other stories, books or films about cheats and tricksters (such as Jolly LLB) Teach legal vocabulary Use pictures (from the textbook) to explain the title Discuss what the students know about the way of life in American towns today and compare it with the story |

Resource 2: Using role play and drama

Students learn best when they are actively engaged in the learning experience. Your students can deepen their understanding of a topic by interacting with others and sharing their ideas. Role play and drama are two of the methods that can be used across a range of curriculum areas, including maths and science.

Role play

Role play is when students have a role to play and, during a small scenario, they speak and act in that role, adopting the behaviours and motives of the character they are playing. No script is provided but it is important that students are given enough information by the teacher to be able to assume the role. The students enacting the roles should also be encouraged to express their thoughts and feelings spontaneously.

Role play has a number of advantages, because it:

- explores real-life situations to develop understandings of other people’s feelings

- promotes development of decision making skills

- actively engages students in learning and enables all students to make a contribution

- promotes a higher level of thinking.

Role play can help younger students develop confidence to speak in different social situations, for example, pretending to shop in a store, provide tourists with directions to a local monument or purchase a ticket. You can set up simple scenes with a few props and signs, such as ‘Café’, ‘Doctor’s Surgery’ or ‘Garage’. Ask your students, ‘Who works here?’, ‘What do they say?’ and ‘What do we ask them?’, and encourage them to interact in role these areas, observing their language use.

Role play can develop older students’ life skills. For example, in class, you may be exploring how to resolve conflict. Rather than use an actual incident from your school or your community, you can describe a similar but detached scenario that exposes the same issues. Assign students to roles or ask them to choose one for themselves. You may give them planning time or just ask them to role play immediately. The role play can be performed to the class, or students could work in small groups so that no group is being watched. Note that the purpose of this activity is the experience of role playing and what it exposes; you are not looking for polished performances or Bollywood actor awards.

It is also possible to use role play in science and maths. Students can model the behaviours of atoms, taking on characteristics of particles in their interactions with each other or changing their behaviours to show the impact of heat or light. In maths, students can role play angles and shapes to discover their qualities and combinations.

Drama

Using drama in the classroom is a good strategy to motivate most students. Drama develops skills and confidence, and can also be used to assess what your students understand about a topic. A drama about students’ understanding of how the brain works could use pretend telephones to show how messages go from the brain to the ears, eyes, nose, hands and mouth, and back again. Or a short, fun drama on the terrible consequences of forgetting how to subtract numbers could fix the correct methods in young students’ minds.

Drama often builds towards a performance to the rest of the class, the school or to the parents and the local community. This goal will give students something to work towards and motivate them. The whole class should be involved in the creative process of producing a drama. It is important that differences in confidence levels are considered. Not everyone has to be an actor; students can contribute in other ways (organising, costumes, props, stage hands) that may relate more closely to their talents and personality.

It is important to consider why you are using drama to help your students learn. Is it to develop language (e.g. asking and answering questions), subject knowledge (e.g. environmental impact of mining), or to build specific skills (e.g. team work)? Be careful not to let the learning purpose of drama be lost in the goal of the performance.

Resource 3: Extract from a story

This is an extract from The Happy Prince by Oscar Wilde.

‘Why are you weeping then?’ asked the swallow. ‘You have quite drenched me.’

‘When I was alive and had a human heart,’ answered the statue, ‘I did not know what tears were, for I lived in the Palace, where sorrow is not allowed to enter. My courtiers called me the Happy Prince, and happy indeed I was. So I lived, and so I died. And now that I am dead they have set me up here so high that I can see the ugliness and all the misery of my city, and though my heart is made of lead yet I cannot choose but weep.’

‘What! Is he not solid gold?’ said the swallow to himself. He was too polite to make any personal remarks.

‘Far away,’ continued the statue in a low musical voice, ‘far away in a little street there is a poor house. One of the windows is open, and through it I can see a woman seated at a table. Her face is thin and worn, and she has coarse, red hands, all pricked by the needle, for she is a seamstress. She is embroidering flowers on a satin gown for the loveliest of the Queen’s maids of honour, to wear at the next Court ball. In a bed in the corner of the room her little boy is lying ill. He has a fever, and is asking his mother to give him oranges. His mother has nothing to give him but river water, so he is crying. Swallow, Swallow, little Swallow, will you not bring her the ruby out of my sword hilt? My feet are fastened to this pedestal and I cannot move.’

‘I am waited for in Egypt,’ said the swallow. ‘My friends are flying up and down the Nile, and talking to the large lotus flowers. Soon they will go to sleep.’

The Prince asked the swallow to stay with him for one night and be his messenger. ‘The boy is so thirsty, and the mother so sad,’ he said.

‘I don’t think I like boys,’ answered the swallow. ‘I want to go to Egypt.’

But the Happy Prince looked so sad that the little swallow was sorry. ‘It is very cold here,’ he said. But he agreed to stay with him for one night and be his messenger.

‘Thank you, little Swallow,’ said the Prince.

The swallow picked out the great ruby from the Prince’s sword, and flew away with it in his beak over the roofs of the town. He passed by the cathedral tower, where the white marble angels were sculptured. He passed by the palace and heard the sound of dancing. A beautiful girl came out on the balcony with her lover.

‘I hope my dress will be ready in time for the State ball,’ she said. ‘I have ordered flowers to be embroidered on it, but the seamstresses are so lazy.’

He passed over the river, and saw the lanterns hanging on the masts of the ships. At last he came to the poor woman’s house and looked in. The boy was tossing feverishly on his bed, and the mother had fallen asleep, she was so tired. In he hopped, and laid the great ruby on the table beside the woman’s thimble. Then he flew gently round the bed, fanning the boy’s forehead with his wings. ‘How cool I feel!’ said the boy, ‘I must be getting better;’ and he sank into a delicious slumber.

Then the swallow flew back to the Happy Prince, and told him what he had done. ‘It is curious,’ he remarked, ‘but I feel quite warm now, although it is so cold.’

‘That is because you have done a good action,’ said the Prince.

And the little swallow began to think, and then fell asleep. Thinking always made him sleepy.

When day broke he flew down to the river and had a bath.

‘Tonight I go to Egypt,’ said the swallow, and he was in high spirits at the prospect. He visited all the monuments and sat a long time on top of the church steeple. When the moon rose he flew back to the Happy Prince.

‘Have you any commissions for Egypt?’ he cried. ‘I am just starting.’

‘Swallow, Swallow, little Swallow,’ said the Prince, ‘will you stay with me one night longer?’

‘I am waited for in Egypt,’ answered the swallow.

‘Swallow, Swallow, little Swallow,’ said the Prince, ‘far away across the city I see a young man in a garret. He is leaning over a desk covered with papers, and in the glass by his side there is a bunch of withered violets. His hair is brown and crisp, and his lips are red as a pomegranate, and he has large and dreamy eyes.

He is trying to finish a play for the Director of the Theatre, but he is too cold to write any more. There is no fire in the grate, and hunger has made him faint.’

‘I will wait with you one night longer,’ said the swallow, who really had a good heart. He asked if he should take another ruby to the young playwright.

‘Alas! I have no ruby now,’ said the Prince. ‘My eyes are all that I have left. They are made of rare sapphires, which were brought out of India a thousand years ago.’ He ordered the swallow to pluck out one of them and take it to the playwright. ‘He will sell it to the jeweller, and buy firewood, and finish his play,’ he said.

‘Dear Prince,’ said the swallow, ‘I cannot do that,’ and he began to weep.

‘Swallow, Swallow, little Swallow,’ said the Prince, ‘do as I command you.’

So the swallow plucked out the Prince’s eye, and flew away to the young man’s garret. It was easy enough to get in, as there was a hole in the roof. Through this he darted, and came into the room. The young man had his head buried in his hands, so he did not hear the flutter of the bird’s wings, and when he looked up he found the beautiful sapphire lying on the withered violets.

‘I am beginning to be appreciated,’ he cried. ‘This is from some great admirer. Now I can finish my play,’ and he looked quite happy.

Resource 4: Completed planning form

| Class | Class IX | |

|---|---|---|

| Passage | The Happy Prince (NCERT, Moments: Supplementary Reader in English for Class IX) | |

| Section | Activity | |

Section 1, from ‘High above the city …’ to ‘I am the Happy Prince.’ Listening |

The teacher reads this section aloud to the whole class. Students have their books closed and listen. As they listen, they draw a picture of what they hear in the section. The drawing will have a statue of the prince on a high column, a swallow sitting at the foot of the prince and tears falling from the prince’s eyes and falling on the swallow’s head. |

|

Section 2, from ‘Why are you weeping then?’ to ‘… and he looked quite happy.’ Listening, reading, writing and speaking |

The teacher asks students to guess why the prince is weeping. The teacher reads from ‘When I was alive…’ to ‘He was too polite to make any personal remarks.’ The teacher organises the class into groups of three students and assigns one of two sub-sections to each group:

The groups read their sections and write a summary together, and then share their summaries with the whole class. |

|

Section 3, from ‘The next day the swallow flew down to the harbour …’ to ‘… and he slept at the Prince’s feet.’ Listening |

The teacher tells students that the prince and the swallow help a third person. In pairs, the students guess who they help and how. They write some lines about their guesses, and a few groups share their ideas with the whole class. The teacher then reads the section aloud to the whole class (while the students have books closed) and asks them to listen out for who the third person is. The teacher checks that students understand that the swallow has decided to stay with the prince. |

|

Section 4, from ‘All the next day …’ to the end of the story. Reading |

The students read the section silently and then answer comprehension questions about the passage in pairs. The teacher dictates answers to the comprehension questions to the whole class. |

|

Resource 5: Planning lessons

Why planning and preparing are important

Good lessons have to be planned. Planning helps to make your lessons clear and well-timed, meaning that students can be active and interested. Effective planning also includes some in-built flexibility so that teachers can respond to what they find out about their students’ learning as they teach. Working on a plan for a series of lessons involves knowing the students and their prior learning, what it means to progress through the curriculum, and finding the best resources and activities to help students learn.

Planning is a continual process to help you prepare both individual lessons as well as series of lessons, each one building on the last. The stages of lesson planning are:

- being clear about what your students need in order to make progress

- deciding how you are going to teach in a way that students will understand and how to maintain flexibility to respond to what you find

- looking back on how well the lesson went and what your students have learnt in order to plan for the future.

Planning a series of lessons

When you are following a curriculum, the first part of planning is working out how best to break up subjects and topics in the curriculum into sections or chunks. You need to consider the time available as well as ways for students to make progress and build up skills and knowledge gradually. Your experience or discussions with colleagues may tell you that one topic will take up four lessons, but another topic will only take two. You may be aware that you will want to return to that learning in different ways and at different times in future lessons, when other topics are covered or the subject is extended.

In all lesson plans you will need to be clear about:

- what you want the students to learn

- how you will introduce that learning

- what students will have to do and why.

You will want to make learning active and interesting so that students feel comfortable and curious. Consider what the students will be asked to do across the series of lessons so that you build in variety and interest, but also flexibility. Plan how you can check your students’ understanding as they progress through the series of lessons. Be prepared to be flexible if some areas take longer or are grasped quickly.

Preparing individual lessons

After you have planned the series of lessons, each individual lesson will have to be planned based on the progress that students have made up to that point. You know what the students should have learnt or should be able to do at the end of the series of lessons, but you may have needed to re-cap something unexpected or move on more quickly. Therefore each individual lesson must be planned so that all your students make progress and feel successful and included.

Within the lesson plan you should make sure that there is enough time for each of the activities and that any resources are ready, such as those for practical work or active groupwork. As part of planning materials for large classes you may need to plan different questions and activities for different groups.

When you are teaching new topics, you may need to make time to practise and talk through the ideas with other teachers so that you are confident.

Think of preparing your lessons in three parts. These parts are discussed below.

1 The introduction

At the start of a lesson, explain to the students what they will learn and do, so that everyone knows what is expected of them. Get the students interested in what they are about to learn by allowing them to share what they know already.

2 The main part of the lesson

Outline the content based on what students already know. You may decide to use local resources, new information or active methods including groupwork or problem solving. Identify the resources to use and the way that you will make use of your classroom space. Using a variety of activities, resources, and timings is an important part of lesson planning. If you use various methods and activities, you will reach more students, because they will learn in different ways.

3 The end of the lesson to check on learning

Always allow time (either during or at the end of the lesson) to find out how much progress has been made. Checking does not always mean a test. Usually it will be quick and on the spot – such as planned questions or observing students presenting what they have learnt – but you must plan to be flexible and to make changes according to what you find out from the students’ responses.

A good way to end the lesson can be to return to the goals at the start and allowing time for the students to tell each other and you about their progress with that learning. Listening to the students will make sure you know what to plan for the next lesson.

Reviewing lessons

Look back over each lesson and keep a record of what you did, what your students learnt, what resources were used and how well it went so that you can make improvements or adjustments to your plans for subsequent lessons. For example, you may decide to:

- change or vary the activities

- prepare a range of open and closed questions

- have a follow-up session with students who need extra support.

Think about what you could have planned or done even better to help students learn.

Your lesson plans will inevitably change as you go through each lesson, because you cannot predict everything that will happen. Good planning will mean that you know what learning you want to happen and therefore you will be ready to respond flexibly to what you find out about your students’ actual learning.

Resource 6: Online literary resources

Here are some links to online literary resources:

- Project Gutenberg: http://www.gutenberg.org/

- PoemHunter.com: http://www.poemhunter.com/

- The Poetry Archive: http://www.poetryarchive.org/ poetryarchive/ home.do

Here are some texts written for teenage English learners:

Additional resources

Here are some links to articles and tips for teachers of English about teaching literature and extensive reading:

- 'Teaching materials: using literature in the EFL/ ESL classroom' by Lindsay Clandfield: http://www.onestopenglish.com/ support/ methodology/ teaching-materials/ teaching-materials-using-literature-in-the-efl/ -esl-classroom/ 146508.article

- ‘BritLit’: http://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/ britlit

- ‘Extensive reading’: http://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/ article/ extensive-reading

- ‘Success in reading’: http://orelt.col.org/ module/ 3-success-reading

References

Acknowledgements

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Resource 3: extract from First Flight: Textbook in English for Class X (2006), National Council of Educational Research and Training, http://ncert.nic.in.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce the material in this unit:

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated below, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/). The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence for this project, and not subject to the Creative Commons Licence. This means that this material may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project and not in any subsequent OER versions. This includes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos.