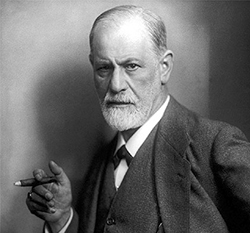

Theories don’t emerge from a vacuum. To understand Freud’s ideas it is useful to get some sense of his life. He was born in 1856 and spent most of his life in Vienna; only moving to London in the last year of his life to escape the hostility of the Nazis.

Theories don’t emerge from a vacuum. To understand Freud’s ideas it is useful to get some sense of his life. He was born in 1856 and spent most of his life in Vienna; only moving to London in the last year of his life to escape the hostility of the Nazis.

While there is every evidence (for example from his letters) that Freud was a passionate man, he didn’t himself have much of a sex life. As far as we know this was limited to his relationship with his wife Martha - and that petered out in his forties. Perhaps not surprising, then, that the repression of sexuality is a strong theme in his work.

As to his education, a distinguishing characteristic was its breadth. He studied classics and history at school; philosophy and biology at university. He was equally at home in the worlds of literature and science. And one of the great features of his theory is that it links our biological being with the meanings that constitute our experience.

Becoming a great scientist was Freud’s initial ambition but - for practical reasons - he eventually turned to what we would now call psychotherapy. He began by studying what others were doing in this field, working in Paris with Charcot who was using hypnosis to treat hysterical patients. Charcot’s clinic was a bit like a theatre, with patients being hypnotised in front of an audience of medical students - as well as occasional members of the lay public.

Freud also tried using hypnosis at first. But he later discarded it in favour of techniques like free association (the patient saying whatever comes into the mind), dream interpretation and closely analysing the relationship between patient and the therapist himself. Freud’s original aim was to release blocked feelings (catharsis), but later it became to help the patient gain insight into the unconscious feelings that led to neurosis.

Freud's theories are best understood as covering three key areas: The first is the idea of the importance of unconscious feelings. Freud’s first case studies purported to show the way that when strong feelings cause conflict, they may be blocked from awareness - repressed. This, however, doesn’t mean that they go away. One way they may express themselves is in the form of neurotic symptoms, usually in some way expressing the underlying conflict.

As an example, a young woman who was disgusted by seeing a dog drink from a household glass developed symptoms where she couldn’t drink liquids. Unconscious feelings may also show themselves in distorted form in dreams. The goal of Freudian dream interpretation is to unravel the different kinds of distortion which mask the motivations underlying the dream. Freud also thought slips of the tongue and the mistakes we make were motivated by unconscious conflicts and feelings.

The second base of Freud’s theories is his theory of psychosexuality and its foundations in early childhood. He related psychosexuality to the pleasurable sensations that come from the stimulation of certain body areas. He saw the young child as going through a biologically timetabled series of stages. Initially, at the oral stage, the erogenous area is the mouth and - as you may have noticed - when babies get old enough to be able, they love putting things to their mouths. (Each stage is characterised by a particular body area, a physical ‘mode’ - at the oral stage, sucking or biting - and a psychological ‘modality’ - at this stage the child is dependent on others for survival and satisfaction.)

The anal stage comes next where the core conflict relates to the requirement of the child to control his/her own body functions to the requests of others. According to Freud, this may lay the foundation for many different kinds of personality characteristics from stinginess (holding on) to creativity (being proud of what you produce!). In particular, it lays the foundation for your style of relating to authority - whether this be conformity or rebellion.

The third or phallic stage focuses on the genital area and in boys takes the form of the famous Oedipal conflict. Feeling close to the mother, and developing an awareness of the relationships of others, the boy may come to perceive the father as a rival, producing feelings of both hostility and fear. Given the child’s focus on the phallus at this stage, this can take the form of unconscious fears of castration.

If all this sounds rather far-fetched to you, think of the extraordinary themes found in the classical fairy tales, where people are frequently eaten (oral aggression) and giants' heads are cut off (castration of the father?). Many psychoanalysts would see the popularity among young children of such bloodthirsty themes as indication of their resonance with children’s unconscious feelings.

The third core of Freud’s ideas focuses on the idea of inner psychic conflict or psychodynamics. Freud saw this as taking threefold form. There is the ‘it’ (usually called the id though Freud himself never used that term) which is our core biological feelings, providing the dynamo of our personality. This may come into conflict with the ‘I’ (or ego) when we realise we may need to restrain the direct expression of these feelings out of realistic recognition of the consequences that could result. Then there is the ‘Above-I’ (or superego) – the values and inhibitions we assimilate through our relationship with key figures like parents – our conscience, if you like. These three aspects of ourselves may come into conflict: "No – you can’t hit your little brother (id desire) because otherwise you will be punished (ego concerns), or because it is wrong and you will feel guilty (superego concerns)."

Although we may not be aware of such inner conflict it creates a sense of tension or anxiety. And so the mind uses certain techniques (‘mechanisms of defence’) for coping with inner conflict. One way is just not to be aware of unconscious motivations (repression), another is to ‘project’ the feelings onto others (‘it's them that are aggressive, not me!’) or to displace it onto other targets (instead of telling the boss what we think, kick the cat when we get home).

Freud certainly changed the way not only psychologists but our culture in general think about what it is to be a person. But whether Freud’s ideas are right or not is an arguable point. There are many psychoanalysts who swear by them (although a lot of them such as the followers of Jung, Adler and Klein give the core psychoanalytic notions their own particular spin). At the same time, it is difficult to find solid support of a scientific kind for psychoanalytic ideas. However, that may not be because they are wrong but because it is just very difficult to scientifically substantiate the kind of ideas that Freud was proposing.

Good science requires the capacity to observe or measure in some way what it is you are investigating. That is quite difficult when your focus is on unconscious motivations which by their very nature don’t show themselves directly. Unconscious feelings may even express themselves in your behaviour in opposite form (as in the defence of reaction formation). Shakespeare knew quite a bit about these things - "methinks she doth protest too much" - but such notions are not easy to put to definitive scientific test.

This is one reason for the extraordinary paradox that, although psychoanalytic ideas have been so influential in our culture, they are taught seriously in only a handful of the psychology departments in British universities (the Open University being one of the handful!). It is also why there has been such controversy recently over whether Freud provides us with the basis for definitive statements about what it is to be human or whether his ideas are merely fantasy. (Freud himself was not always sure about this, describing his ideas as a ‘mythology’ at one point.) The important question this controversy stimulates us to think about, both as individuals and psychologists, however, is this: How far is it possible to study what it is to be human in a scientific way, and if we can’t do it that way, how else can we learn to understand who we are?

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews