Laurie Taylor:

We got to get ourselves back to the garden – lines from Joni Mitchell song Woodstock performed by Crosby Stills Nash and Young back in 1970 I think. I'm afraid that even then when I was some sort of, well at least a weekend hippie I found this Edenic injunction to get back to the garden rather at odds with the prosaic suburban reality of gardening in the UK.

Interested in the Social Sciences? Find out about Open University courses

But that's very much the sort of sniffy attitude which is strenuously attacked in a new book called Radical Gardening – Politics, Idealism and Rebellion in the Garden. Its author is George McKay who's Professor of Cultural Studies at the University of Salford. He now joins me in the studio together with Tim Jordan, Senior Lecturer in Culture, Media and Creative Industries at King's College, London.

It is difficult in a way, George isn't it to start off with to think about the garden as being radical? I mean let's talk about its general image. Generally it's suburban, it's restful.

George McKay:

Look at that song you've just played. They want to go down to a farm, back to the garden. Why do they want to go there? In order to form a rock and roll band. There's this marvellous combination of the garden, the green space, the possibility of escape from your urban environment. And then you're going to go there in order to pollute it with noise and to invert it and turn it inside out.

There's an excitement, there's a possibly, there's a youthful privilege in cultural experimentation in just precisely that song.

Laurie Taylor:

OK. Well Tim, what about this? I mean your image of the garden I suppose I think of it as essentially private; a sort of private place, a place where you're constantly erecting higher and higher Leylandii in order to keep away from the neighbours rather than commune with them. And also just a - may I say - feminine [place]; the idea of the cultivation of flowers in the garden, all those plays in which women enter through the French windows carrying their - are they trugs? - of flowers? Yes, feminine.

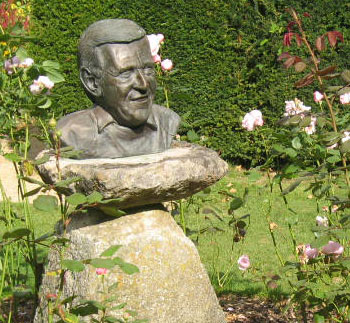

Geoff Hamilton

Tim Jordan:

Maybe this is something to do also with different times of the world, but also with England. And I suppose one of the things that I was thinking about when you were talking then just George was the transition when Geoff Hamilton rather suddenly and sadly was succeeded by Alan Titchmarsh on the Friday night gardening programme, and the concern around that Geoff Hamilton's kind of campaign around peat and organicism would suddenly be overtaken by a kind of Alan Titchmarsh private bonkbuster-writing kind of individual who would kind of take gardens back into the borders and the pansies and the flowers and ...

George McKay:

Yeah, but look what happened there. I mean I think that's interesting, that switch. I mean, before Hamilton [as presenter] there's Percy Thrower, who was actually sidelined out of the job because he starts doing adverts for ICI fertilisers you know and the BBC doesn't really like that; doesn't think it's quite right for their head gardener effectively to be having this little commercial line around chemicals.

And so Hamilton comes in and I think there's a sort of communist tradition actually in Hamilton's family past. You know there's some "fellow traveller" thing going on there. And then also there's this organic sort of impetus on his part.

Titchmarsh comes in and then after Titchmarsh we get Monty [Don] right? And what does Monty do? Monty has this extraordinary focus on the social possibilities of gardens, even doing a series where he tries to get damaged young people to the garden. Because he really believed in that, at that period of time that the garden could sort of cure them and help them and move them into something better for themselves.

Monty Don

Laurie Taylor:

Let's pick up on that song that we were listening to. You know, late sixties, early seventies, flower power movement. I suppose now most people who hear the phrase "flower power movement" tend to sort of write it off as a little temporary aberration, a little bit of silly Californian nonsense.

But you want to rescue it and say that something was going on here which was significant and you want to trace it actually back to the seventeenth century as well?

George McKay:

Well I do. I mean I want to go back and look at the seventeenth century diggers and their strategy of land grabbing and squatting on the land and taking it over and forming a kind of commonwealth, communal space, where they will plant food and that that food will all be distributed freely, will be freely accessible and so on.

And that notion of the seventeenth century Diggers is picked up in the nineteen sixties by the Diggers in the United States, the counter-cultural, the freaks, the new tribes of hippies that were around then.

And also it's picked up a couple of years later – in England there's a group called the Hyde Park Diggers. So that what you've got there is you have the social experimenters from the sixties looking in the past for models and ideas, even if they don't you know; make it perfect or, even if they don't kind of make it absolutely accurate, they want the idea, and they want to take it on and sort of transform it in some other way.

Laurie Taylor:

Rather as they did with, say, the People's Park in San Francisco?

George McKay:

Yeah, so in 1969 you've got this vacant lot in San Francisco which is taken over by the hippies, the professors, the people in the local university and they transform it into a community garden, a new space where also there's rock music played, where there's a children's playground, and so on.

Tim Jordan:

And this is a very interesting piece, that that strand continues on into the kind of development of Silicone Valley just south of San Francisco, into the development of notions of network world and stuff - because a lot of the people who went back to the land, who went back to some of the communes then moved into networking and moved back into San Francisco, and were core to developing some of the ideas around that.

I mean the obvious example is someone like Stewart Brand who was part of the Merry Pranksters, who went back to the land on various communes, was also the man who invented the slogan "Information wants to be free".

Laurie Taylor:

You've got various chapters on a whole variety of ways in which different sorts of gardens announce some form of radical intent.

Tavistock Square

Let's just turn to – I hadn't thought about this before – to peace gardens, the notion of peace gardens. Can you explain what lies behind this and perhaps give me some examples, George?

George McKay:

I was looking at cultures of peace and the way in which culture can be used for peace campaigns, for example the way in which CND in the past has used the festival as part of its cultural expression of its political viewpoint.

And I've also looked at the way in which music, say punk rock music has done that. And I started thinking about some other forms, some other ways in which cultures of peace could manifest themselves.

And in the 1980s lots of municipal authorities, particularly socialist authorities, up and down the land started, as one of their gestures in support of an anti-nuclear campaign, they would set aside a piece of ground in one of their public parks and they would plant it in a slightly different way, design it slightly differently.

It might have bamboo or it might have a cherry tree for the spring blossom. It might have Japanese maples, peace roses, maybe even a little pagoda in some instances. And these became called peace gardens.

And they were seen as the sort of horticultural manifestation of the council's anti-nuclear policy. And this is at the time of the huge debates and protests going on around Cruise missiles in Britain, so it's quite a radical sort of horticultural gesture.

Laurie Taylor:

So it was saying that here is a space which we set aside, here is a garden which is devoted to this. I mean one of the other ones you mentioned that I do know is Tavistock Square in London. Perhaps you'd just describe what what happens there.

George McKay:

I walked through there today in fact. Whenever I come down to London, I come out of Euston, I always go to Tavistock Square and walk through there.

Tavistock Square. In a way it's become a peace garden because of the design elements that are in there. And they include, for example, when you walk through there, if you look at some of the trees that are planted there – and this is the notion of planting as an act of political protest – if you look at some of the trees that are planted there they will have signage at the bottom that says "This tree is planted in memory of the victims of Hiroshima" OK?

Or if you look elsewhere in the garden, there are lots of benches around and they'll be carved "In memory of such and such a life long campaigner for socialism and against nuclear energy" or something like that.

And so you walk through the garden and there are these constant references within that space to political campaigners, to the lives of people that have been involved in it.

Laurie Taylor:

Tim, you're impressed by this. I mean you feel this is a phenomenon which deserves more recognition?

Tim Jordan:

Oh certainly. I think it's very welcome, looking at gardens in this kind of context.

I suppose I'd pose some questions, though, around notions like memory and history, whether particularly in somewhere like Tavistock Square, what you're seeing is not so much radicalism but is a memory of radicalism.

It's a place for contemplation and thinking and so on. But what part it plays in radicalism any more once it's established, once the chair is there, once the statue is there, I'm not quite so clear on.

Laurie Taylor:

Yes I mean one might say the same about the festivals that you talk about. I mean maybe those early festivals, taking over a piece of land, turning it into, [if] you like, a playground, a play garden, [that] quickly evaporated when commercial elements began to take over.

Tim Jordan:

Well, no. In those instances they quickly evaporated when the authorities came in, trashed the ground and in fact in the case of People's Park when the authorities came in and started shooting people.

You know, five people were injured, one person was blinded, one person was killed. Ronald Reagan, who was the Governor of California at the time, sent helicopters in when there were more protests to tear gas the crowds. In fact if a garden can have that kind of effect I'd say that actually it's got a presentism and a power about it.

Laurie Taylor:

People listening now will probably be thinking of one form of gardening which could be described or which immediately suggests it's radical in some way – that's organic gardening. Just perhaps a brief, little tiny bit of a history here. Because you make the interesting point that this organic movement is radical of the right and of the left.

George McKay:

Yeah, if you look at the early decades of the twentieth century you've got the developing organic movement in Britain and in Germany, for example, within Europe; and what you see there is that in Germany it's quite quickly tied into the new agendas and doctrines through the rise of Nazism. And that actually some of the organic precepts include things the Nazi slogans - "Keep the soil healthy" - and this sort of festishisation of the land that you get within Nazi ideology.

So you've got the blood and soil movement for instance, and that doctrine. That's really quite carefully picked up and presented, manifested through organicism as well.

Laurie Taylor:

And even references which I was quite surprised to find the idea that being bound to the soil and part of the soil, the Jews could be picked out as being somehow dislocated and even referred to as weeds, because they had no set permanent home.

George McKay:

Yes, you would look at that for instance, not just Jews, but also Gypsies and Native Americans. These were identified by the Nazis as nomadic tribes and therefore lacking in a close relationship with the soil.

Allotments in Bristol

Laurie Taylor:

Tim, I want to bring you in, because the other contemporary manifestation which people would possibly point to as a, perhaps a sign of the times, is the increasing ways in which the British have taken to allotments. It's about 330,000 allotments now [in] the revival of this movement. It's suggested in George's book that perhaps here we see more examples of radicalism. Do you take it that way?

Tim Jordan:

Well partly. But I think it's questionably also very much part of a kind of middle class concern with organicism and George's book is very powerful on the connection of organicism and the connection with how people conceive of the soil in allotments and so on.

But as also George outlines, allotments in the UK are very much part of a regularised system managed by local authorities, often at threat and sold off at times when local authorities are short of money.

So I think allotments pose a number of problems in that they allow people to garden. When I had an allotment for a short time, [I] took a class of kind of twenty-odd twelve year-olds down so they could pull out a carrot and see what it was like.

Laurie Taylor:

Where would I look then for examples of radical...?

George McKay:

I would look at allotments, yes. In fact I've got this reading of allotments in the book which isn't to do with the practice of "hands in the dirt", it's more to do with the ideas behind the allotment movement.

And they include two which I then make a suggestion that they show that there's a certain anti-capitalist impulse within the allotment movement – probably surprising you, Tim. Your eyes are raising as I say that.

That's based on two areas of thinking about it.

One, is the way in which the rents for allotment are such a powerful rejection of contemporary land values by local authorities. It's almost sweeping - 'you can have this piece of land for your allotment for thirty pounds a year and the land is worth half a million' or something like that.

And then secondly within the allotment when you have all your glut of produce through the year, right? In most instances you're not actually allowed to sell that. You can't have a commercial transaction.

Tim Jordan:

That's true

George McKay:

You have to go through the gift and glut economy.

Laurie Taylor:

I take it neither of you would agree with the contention of some of my old left wing friends the reason we hadn't had a proper proletarian revolution in this country was because the proletariat was far too busy cultivating their gardens.

George McKay:

Absolutely not. There we go.

Tim Jordan:

Certainly not.

George McKay:

Think of the French or the Italians, marvellous gardening traditions and pretty lively with revolution too.

This discussion was originally broadcast on BBC Radio 4 as part of Thinking Allowed, Wednesday 4th May 2011

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews