5.7.1 Plan preparation

Perhaps the first question to ask is ‘What is an emergency plan?’ Dodswell, in his guide to business continuity management, defined an ‘emergency management plan’ as simply:

A plan which supports the emergency management team by providing them with information and guidelines.

(Dodswell, 2000, p. 56)

Another definition, of an ‘emergency preparedness plan’ prepared in the context of chemical incidents, and therefore site-specific, is:

A formal written plan which, on the basis of identified potential accidents together with their consequences, describes how such accidents and their consequences should be handled, either on-site or off-site.

(OECD, 2003, p. 178)

Widen the scope a little and make it cover ‘potential hazards’ to be handled ‘wherever they occur’, and the same definition might apply to local authority emergency planning.

As with any complex process, the procedure may be broken down into a series of more manageable tasks or steps which we will now outline.

Step 1: Develop emergency management policy

The first step is that the organisation must recognise the need for a contingency plan. Then someone or some organisation has to be given the authority and resources to undertake the task. It is crucial that roles and responsibilities are clearly understood at this stage. To be effective, they have to be negotiated at the highest (strategic) level before being implemented. When developing policy, the following factors have to be considered:

the nature of the hazards, community and environment covered by the policy;

legislative and organisational responsibilities;

existing related policies;

public attitudes, expectations and perception of risk;

resource limitations;

the rights of individuals;

accepted emergency management concepts.

Policies must take health and safety issues into account when considering how emergencies will be handled. There is still the need for risk assessments before personnel are committed. Welfare measures also need to be considered. Official guidance reminds us that plans must include the physical and psychological welfare of responders and the need for stress reduction measures (Cabinet Office, 2003).

Step 2: Identify stakeholders

Everyone who has an interest – a ‘stakeholder’ – must be identified and given the opportunity to take part in developing and clarifying a policy.

Activity 11

For an organisation with which you are familiar (it could be your workplace, or an organisation with which you are involved), list the groups you would have to invite to discuss the need for an emergency plan.

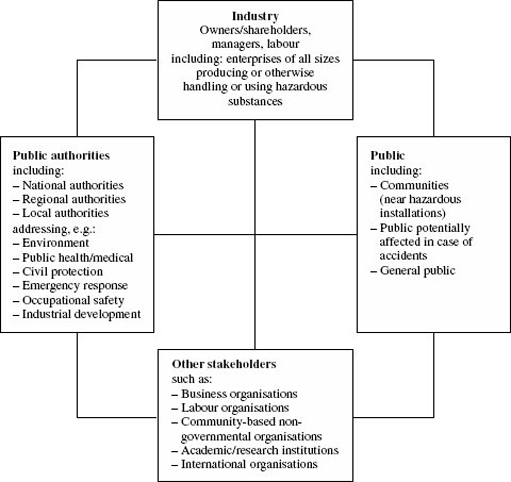

Your list may have included client groups, community groups, industry groups, members of the public, politicians, public and private sector organisations, and staff. In the exercise of civil protection planning, the list of stakeholders is infinite and usually a cascade system is used to consult appropriate bodies. The OECD (2003) illustrates the range of potential stakeholders, shown in Figure 10.

Step 3: Assess vulnerability

Hazards can include technological, social and health risks as well as ‘natural’ ones. A power cut no longer means simply lack of light, heat or the means to cook food. Communities, businesses and governments are now vulnerable because of their reliance on computers for the electronic transfer of information, data and money and for the control of safety systems. Vulnerability assessment is much the same process as any risk assessment, although it may be necessary to stand back and consider wider consequences and on a larger scale. It involves asking four simple questions about risks:

From what? (What hazards exist?)

Of what? (What harm might be caused?)

To what? (Who or what can be harmed?)

So what? (The scale of possible consequences.)

Activity 12

Identify the hazards that could affect your organisation.

Decide on the level of the associated risks.

What would the consequences be if no action were taken?

Your results will obviously depend on the organisation, but by carrying out this activity you have taken an important step in preparing your emergency plan.

Step 4: Select emergency management strategies

This step involves the application of appropriate knowledge, problem-solving and decision-making skills to:

determine emergency management situations and issues;

identify possible strategies;

determine criteria for selecting the strategies to be adopted.

The plan is not – or should not be – an instruction manual or a set of ‘standing orders’ on what to do. People called upon to manage an emergency are usually the same people who cope with the day-to-day running of the organisation. If the plan draws up a set of rigid emergency procedures that override normal management processes, the chances of managers implementing it are remote. Instead, the plan is, or should be, a guidance document advising and reminding the managers of agreements reached over actions and responsibilities. Where decisions or choices must be made quickly, it is a guide to which are the preferred options.

For example, if there is a fire at a chemical plant, the local authority may have to set up a temporary reception centre for people evacuated from the area at risk. There may be several buildings that might be used, and the plan might say which one to choose.

The site may have several entrances. The plan might identify which are the first and second choices of gatehouse to use as the incident control point.

In some cases the person preparing the plan might also be the manager who would have to manage the emergency. More usually, the two roles would be separate. If so, it is important that the planner does not make arbitrary operational decisions. The most effective planning process is where the manager is able to work through the operational issues, and decide on the most effective strategies when not under pressure. The planner then checks that they do not conflict with strategies devised by other managers or, if it is a generic plan that is being produced, with other stakeholders.

Activity 13

Develop a flow chart that illustrates the structure of your organisation's response to an emergency. Identify the links with external bodies.

Step 5: Develop agreed strategies into a plan

This is the process of taking the inputs from the stakeholders derived from step 4, and turning them into the plan document. It involves developing a practical plan from the strategy. This may be circulated in draft form in order to identify and solve potential problems of implementation.

At this stage, administrative aspects need to be considered. These may include financial aspects such as call-out and standby payments or special authority to incur expenditure without recourse to normal approval or tendering procedures.

One key decision is to identify the circumstances that will activate the plan and how the appropriate level of response will be initiated. On-site and emergency service plans may be able to rely on staff on duty, at least in the initial stages. In many cases, however, it may be necessary to call out personnel from home. This is considered in more detail a little later.

It is worth repeating that plans must always be implemented with due regard for occupational health and safety. Anyone who has been on a first aid course will know that the primary rule in helping a casualty is not to put yourself in danger and create two casualties.

The final outcome from step 5 should be a draft copy of the plan itself.