5.1 The structure of a hard disk drive

The next morning, Rupert and Gloria were hunched over a disembowelled computer in Rupert’s office.

“Let’s talk about memory,” said Gloria. “What do you remember – if you’ll excuse the pun?”

“Well, I recall that there are several different types of memory – for example, registers and main memory. But perhaps we should start with the secondary storage because that is persistent memory – its contents are not lost when the power is switched off.”

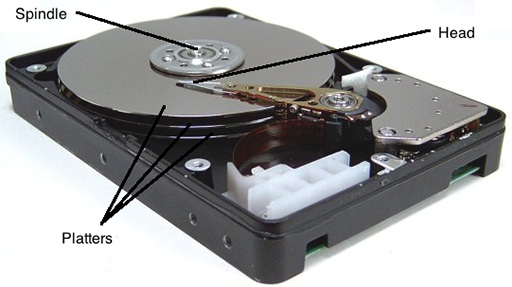

Rupert picked up the component he recognised as the hard disk drive (Figure 15).

“So,” he continued. “Let’s say that I have … hmm … ‘acquired’ a hard drive. How can I find out what interesting data it contains?”

“First, let’s look at the anatomy of a hard disk drive, or HDD, or simply hard disk, as we call them in the trade,” replied Gloria. Extracting a bunch of small screwdrivers from her handbag, she carefully unscrewed the casing. “I don’t advise you ever do this with a hard disk that is still in use,” she said. “Not only will you invalidate any warranty it may have, but also the disk was sealed in a clean environment to minimise dust entering the casing. Even a particle of dust could cause it to crash!”

The casing was soon removed and Gloria and Rupert peered inside (Figure 16).

“You see those three circular disks, stacked up in a pile? Those are called platters and they rotate on that central spindle. They are covered on both sides with a metal that can be magnetised in tiny areas to represent zeros and ones. Each platter has a head that can pass over every part of the disk as it is spinning. This head is able to detect and change the magnetic areas, and so can read and write the zeros and ones.”

“It has been a long time since I have studied any physics,” said Rupert, “but won’t a spot on the edge of a platter have a greater speed than one close to the centre?”

“Yes,” replied Gloria. “Most hard disks now rotate at 7200 revolutions per minute and, of course, each point on the disk has this same rotational speed. However, a spot on the outside of the platter will move further in one revolution than one on the inside, as it has to rotate through a circle with a greater radius in the same time – so it moves faster”.

“Does that mean that the data on the outside of a platter can be read faster than data on the inside of a platter?” asked Rupert.

“Indeed,” replied Gloria, looking impressed.