1.2 Tools and machines

In the previous section I referred to one conception of humans as 'tool-building animals' and suggested that one of the motivations for an interest in constructing artificial creatures might simply be the desire to create more powerful and flexible tools. Consider this question.

SAQ 2

What, in the most general terms, is a tool?

Answer

I would define a tool as any device that helps with the accomplishment of a task. Most physical tools (hammers, levers, screw presses, and so on) are objects that allow humans to increase the physical force they can exert, or to apply it in a more convenient way. Such tools are often referred to as machines.

The whole history of technology is one of machine building. Humans have limited strength compared to many animals, and traditionally we have used animals for tasks that require great power and effort. But we have also learned to build machines that enable us to multiply that strength and deploy it to maximum advantage. So it seems quite reasonable to imagine machines in the form of humans and animals, perhaps stronger, more nimble and less vulnerable than their natural counterparts, capable of extending the power and reach of humans.

Every age in human history has had its own dominant technologies, and the machines of each age will embody these. It is only natural, then, that the lifelike machines imagined by every era have been pictured in terms of the technology of the time. Homer, writing about (although not living in) the Bronze Age, was bound to picture Hephaestus's handmaidens as creatures of gold; and the early Greeks could only have imagined Talos as a bronze warrior.

The 17th and 18th centuries – the period of the Enlightenment, Europe's great Age of Reason – saw the dominance of clockwork mechanisms. Vaucanson himself soon abandoned automata building (although it had made him a rich man) and applied the principles he had learned to the development of mechanised tools, inventing the world's first completely automated loom, controlled by a punch-card technology that anticipated the computer by two centuries. He also invented a revolutionary kind of lathe.

So dominant was the 18th century mechanical picture that thinkers of the time frequently described the universe itself in terms of the metaphor of a great clock, an intricate mechanism moving with the perfect regularity and predictability of clockwork. The French mathematician Pierre Simon Laplace (1749–1827) wrote:

An intellect which at a certain moment would know all forces that set nature in motion, and all positions of all items of which nature is composed, if this intellect were also vast enough to submit these data to analysis, it would embrace in a single formula the movements of the greatest bodies of the universe and those of the tiniest atom; for such an intellect nothing would be uncertain and the future just like the past would be present before its eyes.

So what could have been more natural than to picture the workings of human and animal bodies also as clockwork mechanisms? And to build copies of these that were believed to mimic nature?

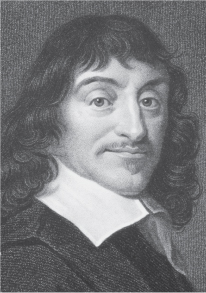

Perhaps one of the most influential thinkers to envisage human and animal bodies as analogous to clockwork machines was Rene Descartes (1596–1650). Descartes wrote:

I suppose the body to be nothing but a statue or machine made of earth ... Thus God ... places inside it all the parts required to make it walk, eat, breathe and indeed to imitate all those of our functions that can be imagined to proceed from matter...

We see clocks, artificial fountains, mills and other such machines which, although only man made, have power to move of their own accord in many different ways. But I am supposing this machine to be made by the hands of God, and so ... you may reasonably think it capable of a greater variety of movements than I could possibly imagine in it ...

Writing later, Julien Offray de La Mettrie (1709–1751), a physician with detailed knowledge of human anatomy, stated baldly that '... the human body is a self-winding machine, a living representation of perpetual motion'.

SAQ 3

If human and animal bodies are essentially just machines, do you think anything follows from this?

Answer

If human and animal bodies are indeed merely very complex machines then it seems a logical next step to say that, with sufficiently powerful technology, perfect copies of such bodies could, in principle, be built.

But this immediately raises an overpowering thought. What is it that most clearly characterises humans as 'tool-building animals'? The obvious answer is the ingenuity that enables humans to conceive, design and build tools in the first place – human intelligence. If artificial human bodies could, in principle, be constructed, what about minds? Would it be possible to build an artificial intelligence?