2.2 Features of diagrams

As there is variety in the types of diagrams we can see and use we need to think more broadly about what diagrams are trying to represent. One distinction which follows on from the discussion above is:

-

Analogue representations: these diagrams look similar to the object or objects they portray. At their simplest they are photographs of real objects and at their most complicated they are colourful, fully labelled drawings of the inner workings of organisms or machines.

-

Schematic representations: these are plans or diagrams which represent the essence of ‘real world’ objects or phenomena, but do not look similar to them. Maps and plans are prime examples.

-

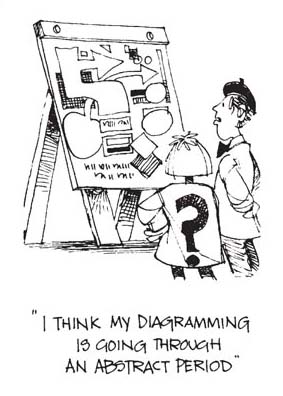

Conceptual representations: these diagrams largely try to describe interrelationships between ideas or processes that cannot be readily observed, but are put forward as a model for acceptance by others. They are mostly used to represent non-visual features where the emphasis can be as much on emotional or abstract relationships as with rational and real relationships. These interpretations may not always be shared by others (because they are based on our internal models) but are essential elements of the diagrammer's own view of the world.

A second distinction arising from this discussion relates to which building blocks (words, lines, symbols, pictures, numbers) that we use to represent things dominate the diagram:

-

pictorial diagrams: pictures and symbols dominate;

-

non-pictorial diagrams: words and lines dominate.

There are also the diagrams where numbers or mathematical relationships dominate, but in this course we deal mainly with non-mathematical relationships and so exclude the charts and graphs most commonly found in scientific and technological texts.