2.3 Some general categories of model

The preceding text has probably suggested several examples of different types of model to you, and at a very broad level, we can categorise the sorts of model we are likely to use in systems work as

Mental models: We have already seen how the ways in which we think and act are shaped by these. As well as the internal representations discussed in Section 2.1, mental models also include language and linguistic models, in particular the metaphors that we use in thinking and talking about situations. Many of these are so common that we lose sight of the fact that they are just metaphors, such as ‘getting to the heart of the matter’, or ‘the bottom line on this is …’. Verbal models are important both as the external representation of our (internal) mental models, and probably as part of the thinking process itself.

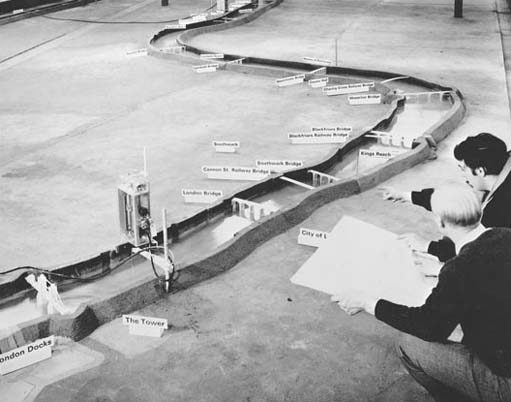

Iconic models: Here, we use some physical material to represent physical aspects of a situation, as in scale models of new products or developments. For example the shape or pattern may be similar, but the scale may be changed, or different materials may be used. Whichever is the case, there is usually a strong visual resemblance between the original and the model. Figure 3 is such a model, actually used to investigate the possible effects of a barrage across an estuary.

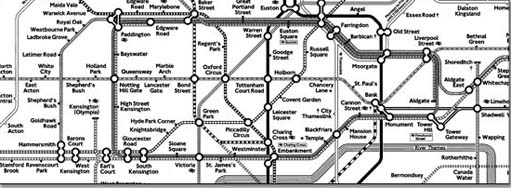

Graphical models: There is a wide range of two-dimensional representations which can be used in systems modelling. They include photographs, maps and plans and other different sorts of two-dimensional diagrams. Figure 4 is a famous example which will be familiar to most UK citizens, and has been a model (in a slightly different sense of the word from the one we are using it in this course) for similar maps elsewhere in the world.

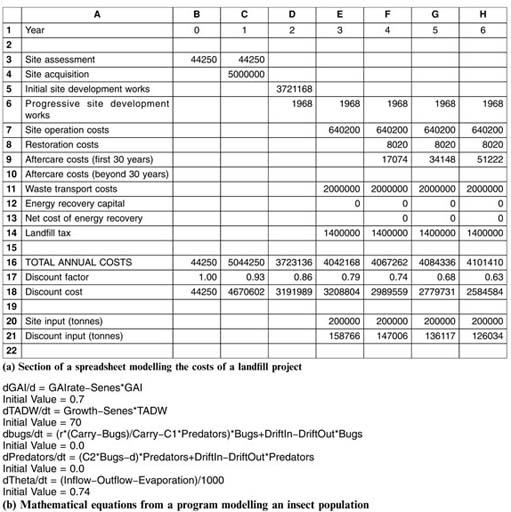

Quantitative (mathematical) models: These models can appear to be extremely powerful and sophisticated, and sometimes, ‘modelling’ is taken to imply only mathematical models. They make use of mathematical techniques to calculate numerical values for the properties of the defined system, and can be used to explore the results of different possible actions. Figure 5 shows two examples.

You have probably encountered examples of these different categories of model in various contexts, but in this pack, we are going to look specifically at the role of modelling within an overall systems framework.

SAQ 3

Categorise each of the following examples using the groupings given above.

-

A one-third scale model steam traction engine

-

A cross-section through a new building

-

‘The market’

-

A set of company accounts.

Answer

-

The steam engine is clearly an iconic model. It is a different size from the original, but is the same shape and probably uses many of the same materials.

-

A graphical model.

-

The concept of a market, as used by advocates of ‘the free market’ is a mental model. However, some economists have also created mathematical models of markets, which they claim behave in a similar way to the mass of buying and selling transactions which occur between people.

-

These are a mathematical model of the cash flows in an organisation. Some of the transactions actually take place, while some items, like depreciation, do not necessarily involve flows of money in any one year, but are purely notional.