4.3 Mind-mindedness

Bretherton et al. (1981) and Fonagy and Target (1997) have suggested that the ability to understand that people have mental states is linked to the ability to develop a representation of self that is a component of the internal working model concept. Fonagy and Target suggest that this ‘reflective function’ serves as a basis of later social understanding, emerging as a natural consequence of generalisations from the early attachment relationship.

Research summary 3: Maternal mind-mindedness and attachment

Elizabeth Meins and her colleagues (Meins et al., 2001) carried out a study of 71 mothers and their infants where, as well as Strange Situation assessments of the infants when they were aged 12 months, data were also collected earlier when the infants were 6 months old. In this first set of sessions, the mothers’ behaviour and talk to their infants during a 20-minute free-play episode, with a range of toys available, were video recorded and subsequently analysed. As well as coding for maternal sensitivity, using a method devised by Ainsworth (Ainsworth et al., 1971), the recordings were analysed to find out the proportions of mothers’ utterances and behaviours that made clear reference to their infants’ mental states. It was found that the mothers of infants who were assessed as securely attached used substantially more of such references. Although the sensitivity codings also predicted attachment security, the latter measures were more powerful, suggesting that parents’ communication styles may be a crucial aspect of the transmission of attachment.

Describing parents who treat their children as ‘persons’, with thoughts and feelings, as ‘mind-minded’, Meins has argued that such parents tend to ‘treat their infants as individuals with minds, rather than merely entities with needs that must be met’ (Meins et al., 2001, p. 332), exposing infants and toddlers to more talk about psychological constructs. From this perspective, exposure to mental-state language and secure attachment are closely linked. Meins et al. (2002), in a subsequent study of 57 mother–infant pairs, looked at mothers’ mind-mindedness when the infants were 6 months old. They also collected data on how well these infants were subsequently able to perform on a range of tasks assessing the capacity to think about other people’s beliefs (so-called ‘Theory of Mind’ tasks). They found that the more mothers’ language made reference to and commented on their 6-month-old infants’ minds, the better the children’s performance on the theory of mind tasks at age 4.

Subsequent research by Meins and her colleagues has clarified a distinction between maternal sensitivity and mind-mindedness:

… appropriate mind-related comments and maternal sensitivity appear to assess distinct facets of infant–mother interaction. For example, imagine an infant begins to cry and reach up his or her arms when the mother walks away to get something from the other side of the room, resulting in the mother returning to comfort the child. This response would appear to be sensitive and socially contingent, but in the absence of the mother voicing her reasons for returning to comfort the child, it is impossible to establish whether the response is mind-minded. If, while comforting the infant, the mother remarks that the child is crying because he or she did not want her to leave or wished she would come back, these would be classified as appropriate mind-related comments. However, if the mother comments that the child is crying because he or she is angry with her or bored, these comments would be classified as nonattuned because they appear to misinterpret the infant’s likely internal state. Focusing on mind-related discourse thus provides crucial information on the mother’s psychological orientation toward her child.

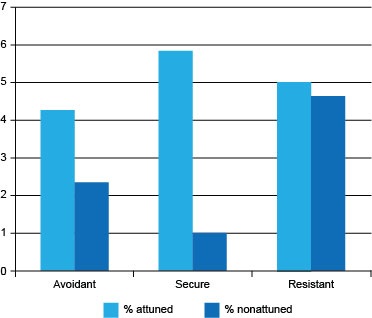

Developing this concept of ‘attunement’ has allowed more detailed investigation of the links between attuned and nonattuned comments made by mothers on their infants’ mental states. In a study of 206 mothers with their infants (Meins et al., 2012), it was found that these two types of comments appear to have independent effects on attachment security. As shown in Figure 12, a higher proportion of attuned comments was associated with a secure infant attachment classification, and a lower proportion of nonattuned comments was also a predictor of secure attachment. The chart also shows that very high proportions of nonattuned comments predict resistant attachment, more than avoidant.