3.3 What does reuse mean?

David Wiley (2007) has been one of the key thinkers and drivers in open content, and he originally proposed the 4Rs of Reuse [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] :

- Reuse – the right to reuse the content in its unaltered/verbatim form (e.g. make a backup copy of the content)

- Revise – the right to adapt, adjust, modify or alter the content itself (e.g. translate the content into another language)

- Remix – the right to combine the original or revised content with other content to create something new (e.g. incorporate the content into a mashup)

- Redistribute – the right to share copies of the original content, your revisions or your remixes with others (e.g. give a copy of the content to a friend). In 2014 Wiley (2014) added a 5th R: ‘Retain’ – the right to keep access to useful texts you have acquired during your studies (electronic copies of core text books, for example) after your course has ended and you have left the institution. He made this addition in response to the phenomenon he describes as ‘disappearing ink’, where to reduce the cost of texts, many education institutions have negotiated deals with publishers whereby the text can be accessed by students at a reduced cost but only for the duration of their course, in contrast to purchasing the full price hard copy which one would obviously retain ownership of in perpetuity.

Wiley (2007) makes the argument that the ‘open’ in ‘open content’ relates to licensing. It is about what the provider permits others to do with the content. It isn’t necessary for all 4/5Rs to be permitted, but the degree to which they are restricted can make a resource less or more open.

Many resources you encounter online have no rights information associated with them (think of most YouTube clips for example). This can place the educator in an awkward position – did the uploader have permission to use that video? If I use it in an educational context am I breaking copyright?

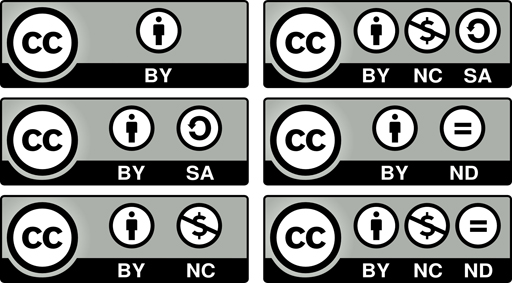

Creative Commons Licence

Most OER projects and repositories deliberately want to encourage reuse so they adopt specific licences to promote this. The most common licence is the Creative Commons licence, although other licences exist.

The Creative Commons licence has a number of ‘settings’, so the rights owner can choose whether or not to place a set of restrictions on the reuse of their material and what those restrictions should be. These are explained on the Creative Commons website. The following Slideshare presentation also explains the different rights and the logic behind them:

- Yann Geffrotin (2007), Creative Commons: Spectrum of Rights.

Alternatively, this blog post from a lawyer explains them: ‘Creative Commons Licenses Explained In Plain English’, or this infographic from the OER Research Hub explains them for teachers.

For its OpenLearn project the OU selected a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence. There are three elements to this licence:

- Attribution – anyone reusing this content needs to attribute the OU as the original creators. They can’t pass it off as their own content, for example.

- Non-commercial – people are free to reuse the content, as long as it is not for commercial purposes. So they can’t take OpenLearn material, repackage it and sell it, for example.

- Share Alike – anyone taking this material and adapting it must share it under a similar licence.

These are actually fairly easy conditions to meet for most cases, and the key to the Creative Commons licence is that it assumes reuse as the default. So the user (or reuser) needn’t ask for permission to reuse the content if they meet these conditions. This doesn’t mean, however, that other forms of reuse are prohibited, just that they do need explicit permission.

The Non-Commercial licence is one in particular that causes some anxiety because what constitutes commercial use can be a grey area. For example, if you use some Creative Commons – Non-Commercial (CC-NC) material in a course and then charge students a fee to study that course, does that constitute commercial use?

In The Case for Free Use: Reasons Not to Use a Creative Commons – NC License (2005), Erik Moller argues that the NC licence is ‘harmful’, while Alma Hales and Andy Lane set out the reasons why the OU adopted the Creative Commons licence in Creative Commons and The Open University (clicking this link should download a document to your device).

Activity 9: Choosing a licence

For your blog posts on this course so far, consider which of the Creative Commons licences you would use, and justify your choice in a further blog post. Then think about two different resources you have produced previously, perhaps teaching resources if you have them, or perhaps something more personal like photographs of a famous landmark, and consider which licence you might choose for these – add your justification to your blog post. If you are content to use Twitter to share your thoughts, Tweet about your blog post, including the hashtags #h817open and #Activity9, and search the hashtags on Twitter to see what other learners have said.