5.2 The human genome

All life is ‘encoded’ chemically in genes. What this means is that the structure of an organism, the organs it possesses, its colouring, and so on are all determined by different genes. A very simple organism may have just a few genes, and a complex one may have tens of thousands. The ‘map’ of an organism’s genes is referred to as its genome. It shows, in essence, which genes give rise to which characteristics or traits of the organism. The word ‘template’ would describe the genome better than ‘map’.

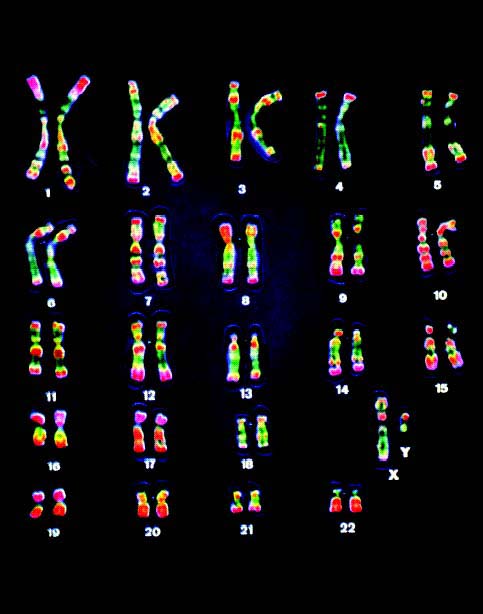

Figure 20 shows the 23 pairs of human chromosomes that constitute the structure of the human genome. These chromosomes contain between 30,000 and 40,000 genes in total. For each human characteristic, such as eye or hair colour, the human genome shows where the genes are that control that characteristic.

Until recently, the idea of mapping the genome of even a simple organism was just that, an idea. The work involved in extracting genetic material, examining it and mapping it to known traits, would be analogous to sitting a dozen people down at typewriters and asking them to write a multi-volume encyclopaedia. It could have been done, but it would have been time consuming (and therefore costly).

Why do it? DNA acts like a computer program. Just as programs instruct a computer to produce certain outputs, DNA instructs the body to develop proteins that make up tissues, cells, antibodies, and so on in a certain way. If there is a defect in a person’s genetic makeup then problems can occur; for example, that person might be more susceptible than average to certain diseases. Mapping the human genome offered some enticing possibilities:

- better understanding of diseases, particularly complex and threatening diseases like cancers

- an understanding of the relationship between different human groups. For example, are we descended from one pair of proto-humans, or did different groups have many different origins?

International effort to map the human genome began in 1995, when it was estimated that the project would require $3 billion and take eight years. But, due to the development of computer-controlled robotic laboratory techniques and improvements in information technology (IT) systems, the Sanger Centre announced in 2000 the first draft of the human genome.