2.2 Certainty and uncertainty in identifications by fingerprint matching

You may have gained the impression that fingerprint analysis is almost foolproof and that the experts, whose opinion is validated by other experts, always make an unambiguous identification. By convention, the experts at the moment do give a yes/no answer to questions of the type: 'Can this fingerprint found at the crime scene definitely be associated with individual X and no-one else?' In court their evidence is usually presented as a definite attribution of fingerprints found at the crime scene to a person who has had access to that crime scene. In almost all cases their opinion is unchallenged and the evidence is accepted by both the prosecution and the defence. At various times in the last few years, following errors in fingerprint attributions, there have been calls for the way that fingerprint evidence is presented to be changed away from a yes/no (binary) presentation to a 'probabilistic' system. A probabilistic presentation would attempt to give the probability or odds that a fingerprint was left by a particular person.

Question 3

When a fingerprint is submitted to the national database did the NAFIS system and now IDENT1 give a probability of a match, a single definite match or several possible matches?

Answer

The NAFIS system gave, and now IDENT1 gives, 15 potential matches and the relevant fingerprint expert then analyses all potential matches and states that either one or none of the matches is correct.

In the past in the UK, and in some jurisdictions today, a minimum number of matching characteristics needed to be demonstrated to establish a match between two fingerprints. As our ability to visualise fingerprints has become so much greater and use of technology has improved, a mechanical, quantitative measure like '16 matching characteristics' asks as many questions as it answers. Among them is the vital question of whether there are any major differences between the prints as well as the matches. The ideal solution is to be able to compare the whole of a print with one on a database with complete reliability. That is not yet completely possible; although the automatic (computerised) matching programs are now very accurate, in the UK, expert opinion on the attribution is always needed in court.

There have been one or two high-profile cases recently where the fingerprint evidence has been shown to be unreliable or wrong and these have raised more generalised concerns about reliability. The following case study illustrates some of the problems.

Case study 1 Shirley McKie: mistaken fingerprint evidence

The very complex case of Scottish ex-police officer Shirley McKie shows some possible consequences for criminal justice if fingerprint attributions cannot be established to the satisfaction of both the defence and the prosecution.

The events started in 1997 when a woman, Marion Ross, was found murdered in her home in Kilmarnock, Scotland. In the subsequent police investigation Detective Constable McKie was assigned to help in the case.

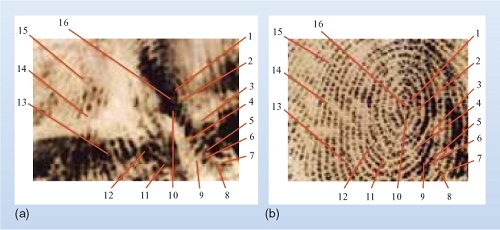

A number of fingerprints were found at the crime scene and at the house of a suspect. The Scottish Criminal Records Office (SCRO) was called in by Strathclyde Police to analyse the prints. A small, decorative tin containing money was found in the home of an early suspect, David Asbury, who had previously done some work for Ross. A latent print on the tin from the suspect Asbury's home was identified as having been made by the victim, Ross. One latent print on a Christmas gift tag from the murder scene was identified as belonging to Asbury (Figure 2). The 16 points of identification (matching characteristics) are shown on each print. You can get an idea of how difficult fingerprint matching is from these prints.

One print from a bathroom doorframe at the crime scene was initially unassigned and SCRO looked at the prints of all those who had potentially been at the crime scene. They claimed a match with a print from DC McKie. However, McKie denied having ever been inside the crime scene, Ross's house.

In the next step Asbury was arrested and charged with murder. The fingerprint evidence tying him to the crime scene (but not necessarily at the time of the murder) was used in the trial. The evidence of Ross's print on the tin found in Asbury's house was critical as he could not explain how it got there and he claimed that Ross had never been to his house. These print attributions comprised the only physical evidence used against Asbury in his trial in 1997. McKie testified under oath that she had not been at the crime scene, even though one of her prints was said to have been found there. The crucial point to note is that those who believed her denial asserted that the rest of the fingerprint evidence was undermined. Despite this Asbury was found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment.

In March 1998 McKie was arrested following a dawn raid on her house and she was charged with perjury for denying that she was at the crime scene, despite the apparent fingerprint evidence that she was there. In May 1999 McKie was unanimously found not guilty of perjury in the Scottish High Court of Judiciary. Several fingerprint experts from the USA and England had independently decided that the supposed match between the crime-scene fingerprint and McKie was definitely incorrect and testimony was given in the court to that effect. The Court rejected the SCRO's fingerprint evidence of a match. This marked the beginning of a long battle for McKie who sued her employers over her arrest and in 2003 lost her case and faced costs that almost forced her into bankruptcy. An anonymous donor subsequently paid her costs which allowed her to continue her campaign.

A consequence of the wrong assignment of the fingerprint initially attributed to McKie was that the fingerprint evidence that helped to convict Asbury was now considered questionable by defence lawyers and the question of who left the now-disputed fingerprint at the crime scene was open. It could conceivably have been left by a so-far unidentified killer. Also, was the attribution of Ross's print on the tin certain? Given these uncertainties, Asbury was freed in August 2003 after the judges accepted that fingerprint evidence against him was unreliable. There has been no final resolution of the murder of Ross.

There are many other twists and turns but McKie sued the Scottish Executive (SE) and in February 2006, before the case was heard, McKie accepted £750 000 compensation from the SE in full settlement of her compensation claim, without admission of liability by the SE.

In a report to the Scottish Parliament former Chief Inspector of Constabulary in Scotland, William Taylor, reported that he found that the Scottish Criminal Records Office's fingerprint bureau was not fully effective and efficient after an inspection he carried out in 2000. He told Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) that there was much good work at the SCRO but suggested that there was an introverted culture where experts thought that their way was the best way. He said, 'The way in which you [i.e. SCRO fingerprint experts] were made an expert was not as good as it should have been, the quality assurance processes were not as good as they should have been'.

In February 2007 a Scottish parliamentary report into the McKie case heavily criticised the management of the fingerprint bureau of the SCRO. MSPs were also critical of the justice minister over McKie's compensation deal and in addition they cleared the fingerprint officers involved of acting maliciously. The report concluded that significant weaknesses still need to be addressed. This report may or may not be the end of the story. There are still strong calls for a judicial enquiry into the whole affair.

Question 4

The technical details of the various fingerprint comparisons in the McKie and Asbury cases are beyond the scope of this course. Based upon the extract from Forensic Science you read earlier in the course, what are the features of fingerprints that the experts would have been looking for in a detailed comparison?

Answer

First of all the expert will classify the major pattern as a loop, whorl, or arch. They will then look for categories of loops, whorls or arches. For example, a loop can be radial or ulnar depending on the direction of flow of its ridges. A whorl can have several different forms including a central pocket whorl or a double loop whorl. Arches can be plain or tented. The expert will also try to assign the print to a particular finger - essential when making a comparison with a known print. The next stage is to examine the detailed features or minutiae. There are actually many of these but examples would include ridge ending, bifurcation, lake and short independent ridge.