As the Covid-19 crisis evolves there is an increasing number of conspiracy theories and articles containing fake information and medical advice circulating the internet. However, there are also well-intentioned attempts to share sense-making about Covid-19. This video on YouTube is one example.

This video is by 'Footman 447', whose intention appears to have been ”to explain the UK government response to COVID19”. The post went viral with over 2 million views at the time of writing. He states the UK government’s strategy was not his idea and identifies himself as a Podiatrist, not an epidemiologist. His stated intent is to “amplify the people who ARE experts". By this he means “people like the excellent Prof Whitty and Sir Patrick Vallance (as opposed to all the overnight virologists I see in the comments)”. However, these experts have been strongly criticised over errors in their conceptual knowledge and strategy. In particular, the idea that letting a virus run through a population can create herd immunity made by Sir Patrick Vallance was heavily challenged by the scientific community because herd immunity is one of the benefits of widespread vaccination. There is currently no Covid-19 vaccine.

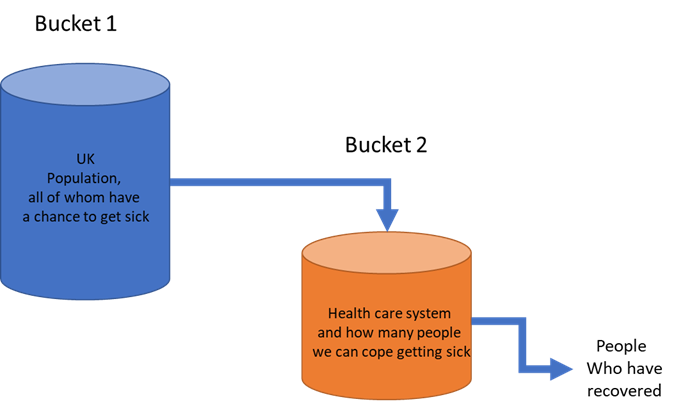

The demonstration in Footman 477's video tries to show what the government seems to think it is doing. Footman 477 uses a bucket and a plastic bottle with a hole to explain how allowing a trickle of people to become infected and pass through the health service avoids a greater flow of people through the health service later. From a systems perspective, this demonstration is a simple system process that has two stages: The population (Bucket 1, which is a population of 65 million) and the health system (which has limited capacity). This system is shown below.

Systems model in Footman 477 YouTube video

Systems model in Footman 477 YouTube video

The key problem with this model is its oversimplification of a complex dynamic process. One does not need to be an epidemiologist to see this. True, the whole UK population can be infected. However, an infection in a population takes time to build up, based on the viral rate of infection and transmission at the earliest stages. At an individual level, every person infected is likely to transmit the virus to others (on average about 2 people, increasing exponentially over time). If a disease can be sufficiently slowed at the beginning its spread will be slowed because the number of transmissions will be reduced if there are fewer infections in the population. On the other hand, if a disease can run through a population, more people will be infected more quickly and at earlier stages.

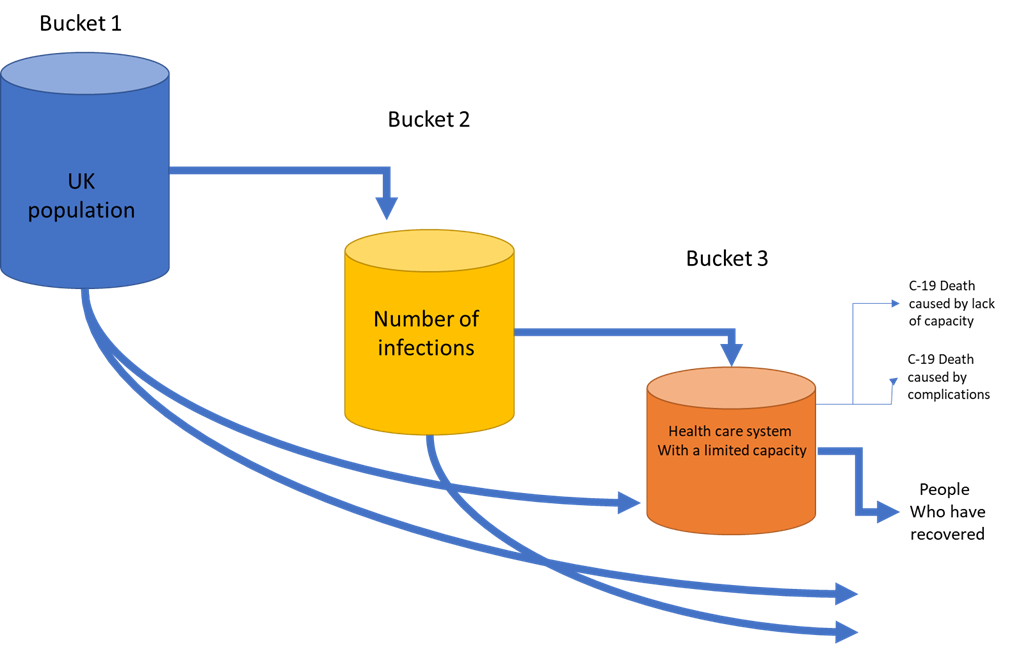

This suggests a more accurate system model would need to have more buckets in order to avoid misconceptions. In diagram 2 below we start with a UK population (bucket 1) in which people become infected (bucket 2). It is from bucket 2 that people will arrive in the hospital. However, some people will recover without hospital care and some people may require hospital care without being infected by Covid-19. Also, some people in the population will become sick with different conditions without requiring hospitalisation and recover on their own. There are deaths from Covid-19 complications and capacity stretch as well as health needs that are not related to Covid-19 but will be impacted because they may rely on the same health system capacity used in combating the Covid-19 outbreak.

Elaborate systems model depicting Covid-19 impact on health systems

Elaborate systems model depicting Covid-19 impact on health systems

A bucket model is useful because it deals with a flow rate describing the movement of people, e.g. how many people over a period. Using water as a metaphor can be useful for understanding system behaviour. However, the YouTube video and explanation of what the government is doing seems to ignore what is actually happening. In an even more elaborate representation of the systemic aspects, one could model additional features, such as impacts on the workforce and external contingencies like freak weather events. This may also alter one’s interpretation of the scenario further. For example, closing schools would impact on parents who are also working in the health service and may not, therefore, be able to continue working if they have children to look after. This would result in a reduction of the health system's capacity to cope. Such a scenario may well have been a consideration in the UK government’s response so far, however, it would also imply policy options that, in this case, the government did not take (such as funding for dedicated child care for NHS staff and support for working partners of NHS workers to be able to look after children).

What seems to be clear is that by allowing the virus to spread, the number of infections will increase more quickly. The more people who get infected, the more people will require hospitalisation. A rise in early infections will mean more people will require hospitalisation sooner rather than later, leading to capacity overwhelm. If the strategy of the government is, as Footman 447 suggests, allowing the virus to spread, but the underlying reality is more like our model 2 in this article, then it follows that allowing the unimpeded spread for longer increases transmission of infections early in the process which brings forward the peak rather than flattening it out (see chart in the tweet below, illustrating the principle of flattening the curve of cases).

Our #FlattenTheCurve graphic is now up on @Wikipedia with proper attribution & a CC-BY-SA licence. Please share far & wide and translate it into any language you can! Details in the thread below. #Covid_19 #COVID2019 #COVID19 #coronavirus Thanks to @XTOTL & @TheSpinoffTV pic.twitter.com/BQop7yWu1Q

— Dr Siouxsie Wiles (@SiouxsieW) March 10, 2020

Footman 477 may well have been well-intentioned. But his explanation may give rise to misunderstandings about the process of infection and response and lead to people being less vigilant in adopting more stringent health measures. Misunderstandings are also the filters through which calamity is perceived. If death rates are high people will ask why more wasn't done to prevent high mortality rates. The message the video gives out is that it is a good thing for people to become infected now rather than later. Some people may believe that it would be good to ‘get it over with’ at a personal level and take insufficient precautions. Considering that they would also infect on average 2 more people suggests they would contribute to an exponential rapid peak. Where we are currently in the process is hopefully still the early rise of infections. The steeper the rise from now on, the bigger the risks to the health service. So, therefore, avoiding infection NOW avoids transmitting the virus to others and helps prevent an exponential increase that will overwhelm health systems.

As the example of a simple YouTube video highlights how one assesses risk and what one should do depends very much on one’s understanding of a system’s underlying complexity. Oversimplification as in many YouTube videos leads to the wrong conclusions, which in turn can lead to the minimisation of risk and acceleration of harms. One should be careful therefore before posting simplistic material on Covid-19 on social media as it's likely to be wrong.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews