10.2 Media coverage of cloning and genetic medical research

Hargreaves, I., Lewis, J. and Speers, T. ‘Towards a better map: Science, the public and the media’, Economic and Social Research Council.

Kitzinger and Reilly, writing about the coverage of genetic research, identified the dichotomous nature of media coverage on this issue. Human medical genetic research is either framed in terms of'the ‘great promise’ discourse focusing on the benefits the science can bring’ or else, the ‘concern’ discourse, focusing on the risks associated with the application of knowledge gained’ (1997: 322). Our study confirms that this dichotomous framework remains very much in operation: reports tend to be scientifically technical, or else avoid all mention of science and concentrate on the ethical aspect of genetic medical research.

The Sun's coverage of the creation of a national Cell Bank is a good example of this dichotomy, to the extent that the same story is reported twice with very different headlines. The first story, on August 28, 2002, led with the headline ‘EMBRYO CELL BANK SHOCK’, clearly prompting the ‘concern’ framework, even if the copy itself is less alarmist:

“HUMAN embryos are to be used by Government scientists to create a bank of cells for medical research. Couples will be asked to donate embryos left over after IVF treatment. The Medical Research Council would then build up a stock of stem cells – the body's building blocks which can develop into any type of cell. Critics claimed there would be undue pressure on IVF couples to make donations. But the Department of Health said: ‘We welcome the initiative’.”

Two weeks later (on September 10, 2002) The Sun reported the same issue with the headline ‘STEM CELLS BANK A FIRST’, suggesting that such a thing was a symbol of scientific progress.

“EUROPE'S first stem cells bank may be set up in the UK within a year, it was announced yesterday. The National Institute for Biological Standards and Control has won a Pounds 2.6million government contract to run one in Hertfordshire. Stem cells – the body's base cells – can be extracted from embryos and adult bone marrow. Doctors will use them to treat such diseases as Parkinson's and diabetes.”

The ‘great promise’ framework relies upon an understanding of the medical potential of genetic medical research, and television and radio reports on this issue tend to also do a better job than the press in explaining why this kind of science is of medical importance. Television, in particular, is consistent in explaining the scientific rational behind the research, and did so in 16 of the 17 news reports on this issue. However, whilst television may be presenting the issue with a mission to explain it, there is little television coverage overall. So, for example, while the House of Lords decision to permit experimentation of cloned embryos on February 28th was top of both I TV and BBC early evening news broadcasts, coverage of the story was not sustained, making only sporadic appearances over the next six months.

Less than a third of newspaper articles by contrast (32 per cent), explain the scientific rationale behind most of this research. And although the Mail was more likely than many other newspapers to include a scientific rationale, it also provides an example of how this scientific context tends to be excluded when the story moves into the ‘concern’ framework, as in the following editorial:

“In America a lesbian couple deliberately produce a test-tube baby that is, like themselves, deaf. Meanwhile, it is reported that a patient of Italian fertility expert Professor Severino Antinori is pregnant with the world's first human clone, though medical opinion fears for its health in the unlikely event of it ever being born. Such stories provide a chilling, warning vision of the nightmare world we could be entering by allowing such irresponsible dabbling with the very stuff of human life” (8th April, 2002).

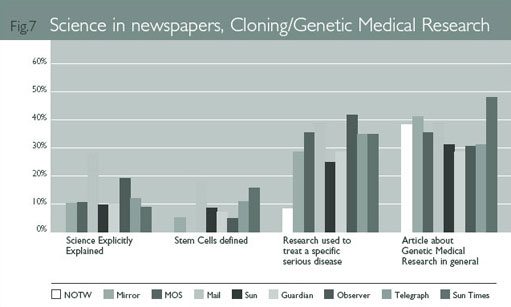

Figure 7 shows how often the scientific context is often omitted from newspaper articles about genetic medical research. The first column ‘Science Explicitly Explained’ represents instances where newspapers have dedicated more than one sentence to explaining the science associated with the story covered.

One could argue that the greater volume of newspaper stories on this issue means that explanations might appear to editors to be repetitive. So, for example, The Sun and The Daily Mirror both ran short explanatory pieces on the day of the House of Lords ruling – (‘STEM CELLS: THE FACTS’ AND ‘HOW STEM CELLS CAN AID MEDICINE’ respectively). The problem with this argument, as we shall see, is the implication that public understanding is such that such repetition is unnecessary.

This lack of clarity may be compounded by the news value given to the more disturbing orfrivolous possibilities of cloning research, with headlines like ‘SCIENTISTS TO CLONE EXTINCT BEASTS FOR THEME PARK’ (The Sun, 20th Aug, 2002) or ‘JUST WHAT THE WORLD NEEDS – ANOTHER TIDDLES’ (The Observer, 17th Feb, 2002). The first of these stories – despite its scientific implausibility – was the subject of a follow up The Sun, through one of their regular ‘vox pops’ featuring the views of a ‘White Van Man’, who opined on August 24th: ‘This is crazy. Scientists could be unleashing something dangerous. I don't think they should be playing around with nature – they might get some nasty surprises…’

Figure 7 also shows that a number of stories in the sample addressed Genetic Medical Research, as opposed to cloning. A smaller percentage of these articles referred to current research helping specific diseases, making it easier for the public to understand why the research was carried out. The following two articles show how journalists and politicians use a reference to a medical disease as a short cut in explaining the research:

“BRITISH scientists yesterday announced a breakthrough in the treatment of cervical cancer – that could be taken in an OINTMENT. They have identified a molecule that kills cancerous cells but ignores healthy ones. The scientists claim it could be sold in ointment form – avoiding surgery or radiotherapy, which affect fertility …” (The Sun, September 6, 2002, upper case in original article).

“I want to make the UK the best place in the world for this research, so in time our scientists, together with those we are attracting from overseas, can develop new therapies to tackle brain and spinal cord repair, Alzheimer's disease and other degenerative diseases, such as Parkinson's,” said Mr Blair … (The Daily Telegraph, May 24, 2002).

On the whole, the dichotomous coverage would, in terms of style, seem to lean in favour of the ‘concern’ framework, which is generally more dramatic and engaging than the coverage of more benign developments in cloning and genetic medical research, which are generally pigeon-holed as ‘science’ stories. Some newspapers do attempt to liven up their coverage, however, with the use of celebrities. Although not mentioned in significant numbers in most media on this issue, celebrities appear in half of all the cloning and genetic medical research articles in the News of the World - in particular the actor Michael J Fox's battle with Parkinsons disease and Christopher Reeve's support for stem cell research.

In terms of public understanding, the main issue here would seem to lie in people's ability to connect these two frameworks. In short, we need to understand something about the science of cloning and genetic medical research if we are to make the ethical judgments that place this issue in the public domain.