10.6 What did we learn from media coverage between April and October?

Hargreaves, I., Lewis, J. and Speers, T. ‘Towards a better map: Science, the public and the media’, Economic and Social Research Council.

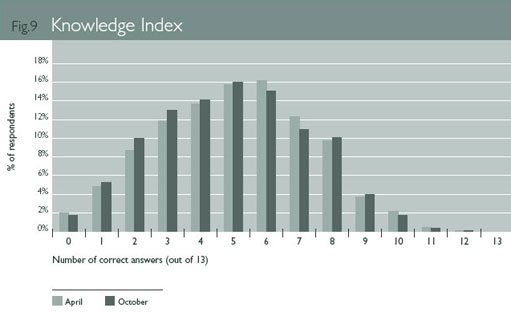

The simple answer would appear to be simple – we did not learn very much that we didn't know before. As Figure 9 suggests, patterns of knowledge or ignorance are remarkably consistent across both surveys.

In terms of question by question comparisons, most differences between the two surveys fall within a three per cent range. Only five knowledge questions showed shifts of five per cent or more from April to October. We found:

-

a seven per cent increase of those who correctly identified a forest as an example of a ‘carbon sink’ (up from 51 per cent to 58 per cent);

-

a five per cent increase of people incorrectly identifying ‘less rainfall in winter’ as a predicted outcome of climate change (from 19 per cent to 24 percent), although correct responses (‘more rainfall in winter’) only dropped by one per cent (from 53 per cent to 52 per cent);

-

a seven per cent drop in those who correctly stated that the bulk of evidence suggested no link between the MMR vaccine and autism (from 30 per cent to 23 per cent), with a 14 per cent increase in those stating incorrectly that there was ‘equal evidence on both sides of the debate’ (up from 39 per cent to 53 percent);

-

a seven per cent drop in those incorrectly stating scientists had recently cloned a human being (from 16 per cent to nine per cent – although the shift here was a seven per cent increase in ‘don't knows’ rather than towards a correct response);

-

a six per cent increase in those correctly identifying the treatment of disease as the main focus of stem cell research (from 60 per cent to 66 per cent), with a five per cent drop in those incorrectly identifying the creation of identical copies of human beings as the main focus (from 11.5 per cent to 6.5 per cent).

Most of these shifts are still too small to be anything other than mildly suggestive. The only discernible pattern in these responses is a small shift in the understanding of stem cell research, away from fears about the cloning of human beings, and towards an awareness of the use of stem cell research for treating disease (a point we shall take up shortly).

Overall, however, most increases and decreases in knowledge are minor and scattered fairly arbitrarily. This suggests that, despite fairly persistent media coverage of these issues, there is no significant increase in public understanding. This does not imply, however, that the media coverage has had no impact on public understanding, merely that any impact on knowledge is fairly consistent over time. This finding is very much in line with other studies of public opinion, which tend to find that, unless subject to major media campaigns, changes are gradual and long-term (see, for example, Page and Shapiro 1992). For those wishing to influence public understanding, this not only requires remaining (to use current political jargon) ‘on message’, but doing so in way that establishes or fits within the overall framework of news reporting.

We shall develop our understanding of the media's role when we look in more detail at knowledge of the three issues, when some interesting patterns emerge. As we shall see, the framework for understanding an issue may develop fairly quickly in a burst of coverage (as with MMR), or with repetition of longer periods of time (as with the other two issues). This presents a real challenge for anyone seeking to influence public opinion.