7.1 Studies on animals’ understanding of ‘seeing’

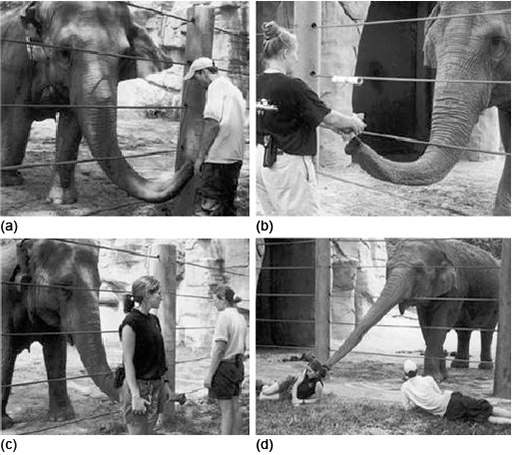

While chimpanzees have been the animal most frequently focused on by researchers interested in Theory of Mind (ToM) in animals, the abilities of non-primates have also been studied. Donna Nissani (2004) discusses some studies she has carried out with elephants. In one set of studies, Nissani used adapted versions of studies on chimpanzees’ understanding of seeing (carried out by Povinelli and Eddy, 1996). Figure 14 shows some scenes from Nissani’s studies.

As you can see from Figure 14, the elephant is required to make a choice, which will either be ‘correct’ (will gain them food) or ‘incorrect’ (will not gain them food). In order to get them used to the general procedure, they are first presented with a number of trials where they need to learn to choose between a piece of food and a rock, using their natural begging gesture (image (a)). They are then presented with the experimental trials in which they are required to choose between a human who can see them, and a human who cannot see them (images (c) and (d)).

Now watch this video: it shows the procedure used by Nissani in this series of studies, which looked for evidence of an understanding of ‘seeing’ in elephants.

Transcript: The procedure used by Nissani in her series of ‘seeing’ studies with elephants

Nissani (2004) reported that elephants initially performed poorly, failing even to distinguish the presence of food − as determined by the food versus rock task (Figure 14 (b): the elephant gestures towards a human holding a rock, rather than one holding food). However, the elephants soon learned to beg correctly (e.g. approaching the human who was facing them, and thus could see them, rather than the human who was facing away) in all the conditions, on most of the trials (around 70%) in which they were tested. They performed in the facing and away-facing condition as well as the chimpanzees in a previous study by Povinelli and Eddy (1996), and outperformed the chimpanzees in other tests (such as, when a bucket was placed over the head of one experimenter, obscuring their vision, while the other had no bucket over their head). But despite the elephants performing better than the chimpanzees in Povinelli and Eddy’s study, they nevertheless begged incorrectly around one-third of the time. So, as Nissani points out in the video, findings from her studies remain equivocal − or inconclusive − on the issue of whether elephants do understand seeing.

Considering the issue of how methods and study designs used might influence the results obtained, Nissani identified a number of methodological issues with the original Povinelli and Eddy chimpanzee studies. She pointed out that these factors may have had an impact on the chimpanzees’ ability to demonstrate an understanding of perception in these studies. In particular, Nissani notes various aspects that made the procedure artificial and unnatural (such unnatural procedures are said to lack

- The required ‘begging’ (for food) gesture used was ‘natural’ for the elephants, but (most likely) not for the chimpanzees in the original Povinelli and Eddy studies.

- The elephants in Nissani’s studies had been raised in more natural conditions, whereas the chimpanzees in the original studies had mostly been born in captivity and subjected to experimentation for most of their lives.

- Povinelli and Eddy’s studies used young chimpanzees, between the ages of 5 and 6 years.

- The way in which the experimental and control trials were set up in the original procedure, and the nature of the rewards offered, made it quite plausible that the chimpanzees may have misunderstood what was required of them, and/or they may have lacked motivation to carry out the intended task (e.g. owing to a lack of sufficient rewards being offered in the test trials).

In her adapted studies, Nissani addressed many of the methodological issues identified. For example, she used adult elephants, and tried to create a more natural context by using tasks and behavioural responses that occur more spontaneously in a naturalistic setting. As mentioned earlier, the performance of Nissani’s elephants was better than that of the chimpanzees in the Povinelli and Eddy studies (although the elephants still made errors around one-third of the time).

Nissani also reported replicating the original Povinelli and Eddy study with chimpanzees. She made procedural variations in order to address many of the issues she identified, including using adult chimpanzees (in a zoo setting) who had not previously taken part in psychological experiments. She also made some more subtle adjustments: for example, altering the way the practice and test trials were organised, and the way in which the rewards were offered. Nissani found that the performance of the chimpanzees was improved (they performed above chance levels, which means they were not just choosing randomly), with findings comparable to those obtained with the elephants (Nissani, 2004).

These various procedural adaptions demonstrate the importance of paying careful attention to the methodological details of these types of laboratory studies, since relatively minor variations may influence the outcomes.

The issue of laboratory studies being artificial, and the extent to which they can be said to have ecological validity (in other words, to represent behaviours and abilities that occur in a naturalistic setting) is important to keep in mind when evaluating the results of comparative research. As you have seen, researchers such as Nissani have attempted to maximise the ecological validity of laboratory studies by using contexts and tasks that are more akin to what occurs in an animal’s natural environment. Some of these studies have found that animals do appear to show evidence of abilities, which previous studies using more artificial contexts suggested they did not possess, such as the understanding of seeing. Another approach, however, is to observe animals’ naturally occurring behaviours in fully naturalistic settings. You will consider this approach in the next section.