2.4 The role of avoidance

The cognitive model of panic disorder stresses the role of catastrophic interpretations in panic attacks. However what explains why people hold onto these beliefs – sometimes in the face of lots of evidence to the contrary? For example, a person with panic disorder may have a persistent belief that they are at risk of a fatal heart attack – despite having been told (on multiple visits to hospital emergency rooms) that there is no sign of problems with their heart.

One idea that has been put forward is that people hold onto their catastrophic interpretations because – simply put – they do not get the chance to learn that they are wrong. Why is this?

Imagine someone who gets anxious any time that they get slightly breathless because of their catastrophic misinterpretation that this means that they are struggling to breathe, which means that they are going to suffocate, which means that they are going to die.

So what do you think that person might end up avoiding if they are worried about feeling even a bit breathless?

Activity 8 Avoidance behaviours

What kinds of things (activities, situations, places) might make a person feel a bit breathless?

Discussion

There are physical activities that are normally (and safely) associated with feeling a bit breathless (especially if the activity is hard or you are not so fit!) – for example, walking up a hill, doing sports or having sex. There are also lots of activities or situations or places that might make a person a bit anxious and where a normal reaction might be to start breathing a little faster – like making a presentation at work, finding a spider in the bath or being somewhere really crowded.

Looking at your list, if a person wanted to avoid feeling breathless what activities, situations or places might they start to avoid?

Discussion

A person who wanted to avoid anything that might make them feel breathless might stop hill walking with their friends, playing football with their kids, or having sex with their partner. They might seek work on the basis that it was unchallenging, get their partner to check the bath before they used it and avoid crowded places like music festivals or supermarkets.

You can see that avoidance of things that are thought to lead to a panic attack can quickly shrink a person’s world. This is one reason why panic disorder is often associated with agoraphobia, which is a phobia of open or crowded places or of going outside the person’s home.

Avoidance ‘coping’ behaviours

In addition to avoiding activities, situations and places, a person with panic disorder may also carefully do particular things to help them cope with the things that worry them. An example of this might be that a person who is worried about feeling breathless when walking up a hill might start taking deep breaths.

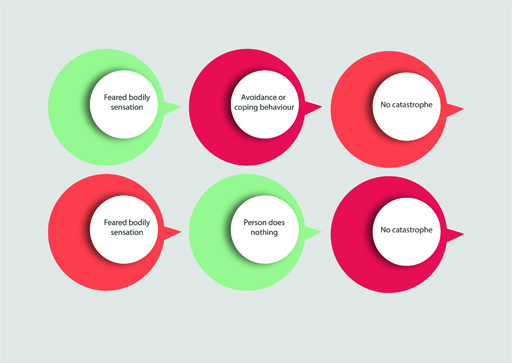

How do these coping and avoidance behaviours prevent a person learning? This is illustrated in Figure 7.

In the first sequence when the person engages in their avoidance or coping behaviour and then nothing terrible happens (or at least they don’t die) the person links the outcome of ‘no catastrophe’ to their avoidance or coping behaviour. They might think: ‘I managed to keep myself alive because I took careful deep breaths and walked up that hill really slowly.’ However, as the second sequence shows, by engaging in these behaviours the person fails to learn that they would not have died even if they had not done the avoidance/safety behaviours.

Avoidance and coping behaviours thus actually work to maintain panic disorder because they stop a person from learning that their feared bodily sensations are not as dangerous as they think they are. Moreover some coping and avoidance behaviours may actually make things worse – for example breathing deeply and quickly (as you might if you are in a bit of a panic) actually leads to hyperventilation, which can lead to a person feeling more short of breath.