Find out about The Open University's Psychology courses and qualifications

Panic buying is an emerging issue during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 across the world. The term panic buying implies fear, namely the fear, based on the anticipation that important goods (food, water, toilet rolls) will run out. In many ways, this is a fear about losing control over our lives, and framed in these terms panic buying is a way of regaining control. A large part of fear is the physiological reaction to stress that can colour people’s decision-making and propels individuals to avoid the fearful threat from becoming a reality. However, what is equally important to understand in panic buying is the role that social perceptions play, in particular, the social perceptions of other people’s behaviour.

The fear of missing out

Fear provides a collective background state that is shared by many people, meaning they all respond to varying degrees to their sense of foreboding, anxiety, and physiological state. One particular type of fear that also seems to be highly relevant here is the fear of missing out, created in panic buying. However, explaining panic buying as merely being fear-based does not provide a satisfactory level of explanation of the problem of panic buying. Instead, we must look to norms to understand the escalating dynamic.

Norms shape most day-to-day behaviours. People have normative beliefs about events, things, about themselves and other people. These beliefs inform and influence people about how they and others should normally behave in any given situation. There are shared norms for pretty much everything humans do. They are the taken-for-granted rules of conduct in a society, but often people are not especially aware of them, and they generally remain unquestioned. Personal norms refer to the behaviours and values that apply to a person, as opposed to what others do. They are often organised around people’s necessities such as work, children and family as well as personal needs and values. (Such as when to get up for work, when to get out of the house, when and how you pick up your children, which side of the bed you sleep in, and what brands you buy in your shopping).

Norms are useful because they allow us to function without having to think too much about the reasons why we do things. Once a norm is in place, people generally adhere to it because it makes life easier. Just as much as personal norms regulate individual behaviour, shared norms regulate activities in large social groups and prescribe what is allowed, what is prohibited or just frowned upon.

Most countries hold sufficient stock for people to ‘poop for 10 years’ to paraphrase the Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte.

Norms are important in times of crisis. In historic China, regions with stronger Confucian norms had fewer peasant rebellions and conflict during economic shocks, suggesting that shared norms organised around values are highly relevant to how societies function as they adapt to large crises.

Crises can massively disrupt the framework of norms people usually inhabit - things taken for granted can no longer be assumed. This is the context the UK and practically any country is finding itself in now during the COVID-19 pandemic. Panic buying at the beginning of the UK’s mobilisation efforts around the 20th March illustrates some of the complex interactions of different type of norms, and the emergence of new norms (that in this case are less helpful), as the old norms (work, socialising, entertainment, shopping) are becoming more tenuous and difficult to maintain.

The symbol of panic buying - toilet rolls

In the UK as elsewhere in Europe, the humble loo roll has become symbolic for panic buying and reveals some of the underlying social norms that are also driving it. Under normal conditions, people’s lives are structured by habits and conventions in a normative behavioural sense. Most people have a norm around what, when and where and how much they shop groceries each week. Most people do not buy that many loo rolls usually, perhaps enough to get by for a week. Indeed most countries hold sufficient stock for people to ‘poop for 10 years’ to paraphrase the Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte.

In high demand - toilet rolls have become a sought after item during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In high demand - toilet rolls have become a sought after item during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Loo roll is an essential item in our society due to the prevalence of water-based toilets. Other cultures do not share this norm because they have different toilet rituals and thus different norms for washing and cleanliness. So, for the majority of UK citizen toilet paper is a normal-to-use and expected essential item, and the sudden unavailability becomes a matter for hushed anxiety (at least in Britain which has an uncomfortable relationship with conversations about poo in any case).

Some people may also wrongly associate a virus with sniffles or digestive symptom issues that might give the impression that more toilet paper is needed. Alternatively, people worried about being in longer-term lockdown may just be worried about running out of toilet paper while secluding and are buying more toilet paper simply as a precaution. This type of thinking may well have been the kind of deliberation in people’s minds at the beginning of this phenomenon. If these were the considerations of just one individual, this would not create a problem. It becomes a problem because so many people are doing the same thing at the same time. And this is what creates a vicious spiral.

Fake images may have been used to maliciously seed panic buying. Social media makes it easy for norm violation signals to spread.

Two theories which explain the recent activities are ‘emergent norm theory’ and ‘signalling theory’. Emergent norm theory is a social psychological theory often used in disaster psychology. The idea is that in disasters existing norms in large groups of people break down and are replaced by new, spontaneously emerging norms. These can be helpful (for example, people helping each other to escape the world trade centre during 9/11), or counterproductive as in looting and panic buying. Signalling theory in a social context is about how behaviours and events signal the status of a norm other people are following.

The influence of social media

It is unclear precisely what precipitating factor started panic buying in the UK, but is likely to be a combination of factors that are impossible to attribute to a single event. The volatility and uncertainty created by fear, lack of trust, conspiracy theories, fake news, lack of leadership and ignorance of the supply in the country all contribute to a climate in which new norms can emerge if the old norms, relating to the availability of stock are perceived to be violated.

An isolated local shortage problem or images of empty shelves on Facebook may have signalled such a violation in a supermarket. This also includes the possibility that fake images may have been used to maliciously seed panic buying. Social media makes it easy for norm violation signals to spread and for the emergent new norms, that they signal, to be amplified in a way that looks like a viral contagion. Not only do these signals show what norms are violated, but simultaneously demonstrate the new norm people seem to be adopting (e,g, they panic buy) in order to regain control over their lives.

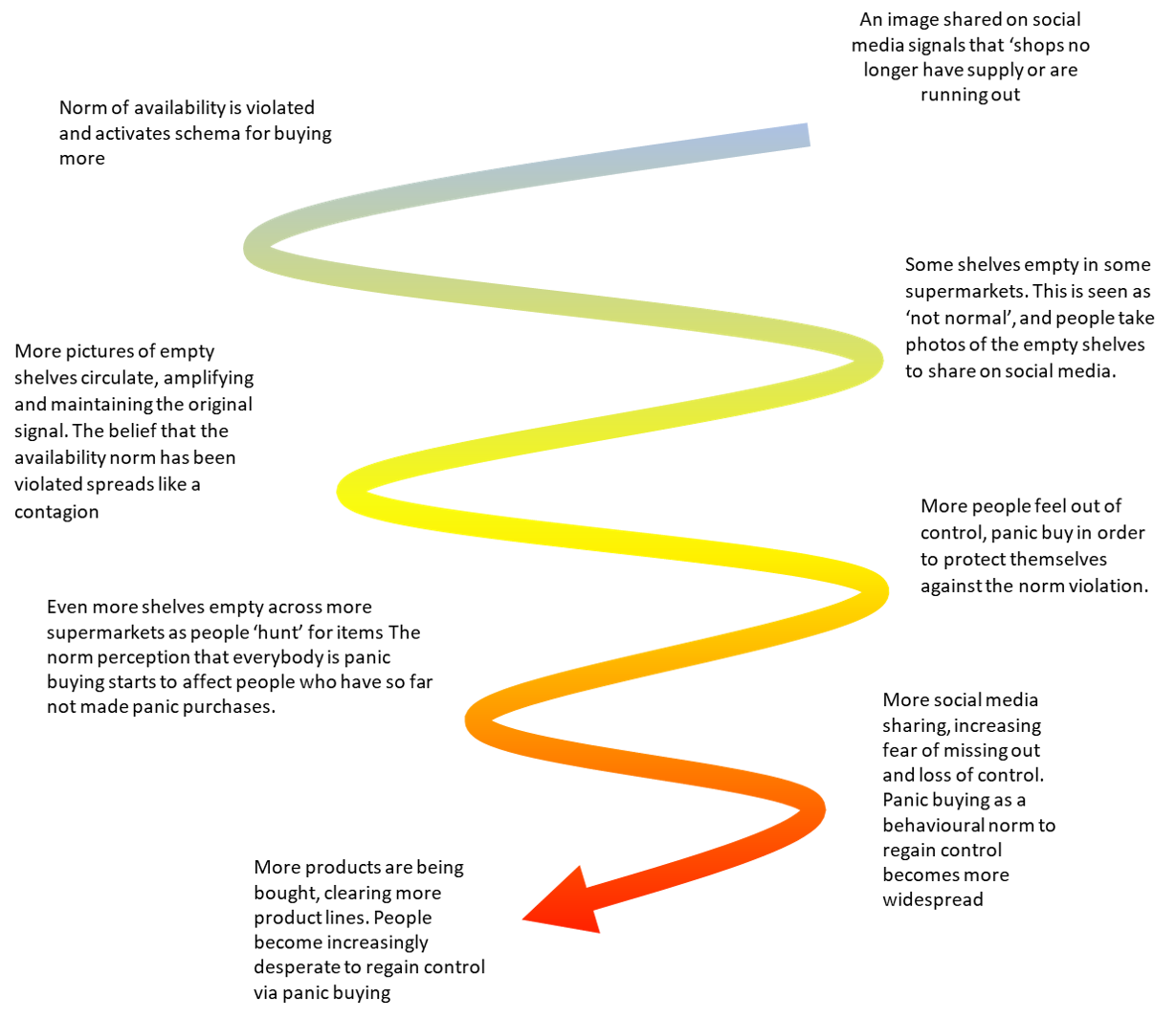

The following diagram shows the sequence of events in a spiral race to the bottom, fuelled by the combination of emergent norm-perceptions and signals that amplify both fear and resulting restocking issues in supermarkets.

Diagram 1: Panic buying downward escalation.

Diagram 1: Panic buying downward escalation.

Supermarkets have already begun to change rules about quantities purchased, and the times for when health workers and the elderly and vulnerable can shop. However, this might also amplify the perception of scarcity.

The perception that a norm has been violated is based on subjective judgement. Accurately assessing whether the availability of food and other items is threatened is difficult to do without more information. Images shared by trustworthy friends on social media provide a powerful impetus to process this information selectively, regardless of the underlying reality. Similarly, a lack of trust in governments can also lead to perceptions that despite reassurances, the reality is different. Other psychological effects, such as confirmatory bias and the mere exposure effect, can distort people’s understanding of issues.

The mere exposure effect relies on the idea that preferences for information, products, people or ideas, is based on how often it is repeated. The more often a message recurs, the more likely people are to believe it is true. Considering the number of Facebook shares of empty shelves and comments on those threads, there is much exposure to the idea that food is running out compared with the one television address or radio interview with a government official stating the opposite is true.

If you or someone in your family become ill with COVID-19 and need the hospital, there may not be enough staff for you to get treatment. COVID-19 can kill. Please shop sensibly.

Thus, a foundation for emergent norms becomes established that has little actual basis in the reality of the supply chain situation. If people continue to panic-buy, the main problem currently and in the future is the restocking of shelves. As supermarkets are likely to experience a significant shortage of staff owing to COVID-19 infections, their capacity to restock will potentially become more limited, highlighting the risk that the signals for activating panic buying norms may well continue into the foreseeable future.

Four ways to prevent panic buying

Here are some examples of what strategies could be used to counter panic buying (short of an armed presence in stores to prevent further escalation of behaviours). The key is to prevent the spread of the emerging harmful norms and reduce the amount of signal that triggers the behaviour.

1. Consistent messaging and framing: Messages about supplies and the harms caused by panic buying must be repeated consistently and frequently by government, media and supermarkets. Such messaging needs to focus on signalling the availability of food as well as the costs of panic-buying behaviours to society, to others and also relevant to themselves. An example of such a message could be: “Your extra purchases cause health workers to be unable to find the goods they need. This could result in them not being able to perform their work. If you or someone in your family become ill with COVID-19 and need the hospital, there may not be enough staff for you to get treatment. COVID-19 can kill. Please shop sensibly”.

2. Reduced social media sharing of signals: The prevalence of empty shelves and other scarcity signals on social media needs to be countered. Facebook can selectively block posts based on content (as a recent glitch in its software that hid information posts about COVID in the week ending on the 22/03) showed. It may be necessary to prevent people from sharing images of empty shelves to avoid information contamination. However, this also would create strong concerns about liberty and freedom of expression, and so maybe an unattractive option in countries with strong rights representation. As a minimum, one should expect governments and social media companies to work to tell people to avoid sharing ‘empty shelf porn’ on Social media and making social media users aware of the contagious nature of emerging norms and users’ role in not transmitting those that are harmful.

3. Removing the signals from the environment: Supermarkets might change their operations to becoming online only with vulnerable and non-internet users being allowed to visit stores to order deliveries. This way, no shelves can be seen, and the signal that shelves are empty will be interrupted. Queues of people forming outside that are another signal for the availability of stock would also be eliminated.

4. Restoring individual control: In parallel to the above ensuring that supplies are in the shops is critical to reducing the feelings of fear and uncertainty resulting from the perception of a loss of control. If this cannot be restored, and visibly demonstrated the emerging norms will be more prevailing

Fundamentally, the situation requires transparent explanations of what is happening, focusing on accessible messaging and explanations, such as those provided in the above article. If people can understand the spiral nature and race to the bottom, it will become easier to connect the impacts panic buying has on health service workers and the vulnerable with being a personally relevant consequence of people’s individual conduct.

This article was originally published on Medium by Dr Volker Patent on 22 March 2020.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews