The Covid-19 pandemic has resulted in nearly two million people dying and tens of millions infected worldwide. This pandemic impacts global health not only via direct infection for millions but also through various other indirect ways. For instance, it has impacted on the United Nation’s Agenda 2030’s Sustainable Development Goal 3 (SDG3), one of the 17 goals, that aims to bring about healthy lives and wellbeing for all (UN Sustainable development, 2020). But can a pandemic, unheard of less than a year ago, potentially derail the SDG3 health for all targets after five years of progress?

Let’s explore 5 specific ways in which COVID-19 has impacted on SDG3 progress in relation to 5 out of 13 particular targets (SDG3 Tracker, 2020) that are aimed to specify the goal 3:

- Target 3.1: Maternal care and reproductive services to reduce maternal mortality;

- Target 3.2: End of preventable deaths of children under 5 years of age;

- Target 3.4: Screening and care for non-communicable diseases;

- Target 3.8: Universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services; and,

- Target 3.D: Strengthen the capacity of all countries for early warning, risk reduction and management of national and global health risks.

1: Disruption to maternal care and reproductive services

Target 3.1 of SDG3 aims to reduce the global maternal mortality (i.e. where a woman dies from pregnancy related causes while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy) ratio to less than 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030 (UN Women (2020)). Improvements in formal health services (technically referred to as ‘institutional delivery’) are one of the crucial ways of achieving this target in several low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Countries that already had lower levels of institutional delivery prior to COVID-19 are going to be further impacted. For example, only 4 in 10 women in Nigeria, 5 in 10 in Mozambique and 6 in 10 in Tanzania and Kenya reported institutional delivery (Figure 1). In other words, 4-6 out of 10 women in these countries delivered without any assistance by skilled care in a health facility prior to the pandemic.

Figure 1: Percentage of live births delivering at a health facility in the five years preceding the Demographic Health Survey in nine African countries

Data taken from the Demographic Health surveys of Kenya (2014), Malawi (2015-16), Mozambique (2011), Nigeria (2018), South Africa (2016), Tanzania (2015-16), Uganda (2016), Zambia (2018) and Zimbabwe (2015) that are nationally representative

Source: STATCOMPILER tables

Due to COVID-19 several countries have witnessed a fall in institutional deliveries. This is mainly due to government and community health workers increased focus on COVID-19 related activities, including testing and tracing, in addition to provision of health care and recording of COVID-19 related activities. Ambulance (and other) services have also been busy with COVID-19 related work, while private hospitals in some parts of the world have decided to close or work in a limited way during the pandemic. Finally, reports have suggested that some women might also be reluctant to deliver in hospital due to the fear of contracting COVID-19. While data needs to be collected to understand the scale of COVID-19’s impact, early evidence from India suggests that in some districts institutional deliveries have reduced to less than 25% (from 75% pre pandemic) as highlighted by Sachin Jain, state coordinator of the Vikas Sansad Samiti (a non-profit organisation in Bhopal, India) (Source: Hindustan Times, June 16, 2020). This dramatic drop in provision, when a woman does not have access to health services with skilled staff, will result in an increase in maternal mortality. In addition, utilisation of other reproductive services including maternal checks have reduced. For example, IVF (In vitro fertilisation) services (and other family planning services) have halted in many parts of the world during 2020, resulting in further disruptions to reproductive health services.

2: Preventable deaths of children under five years of age

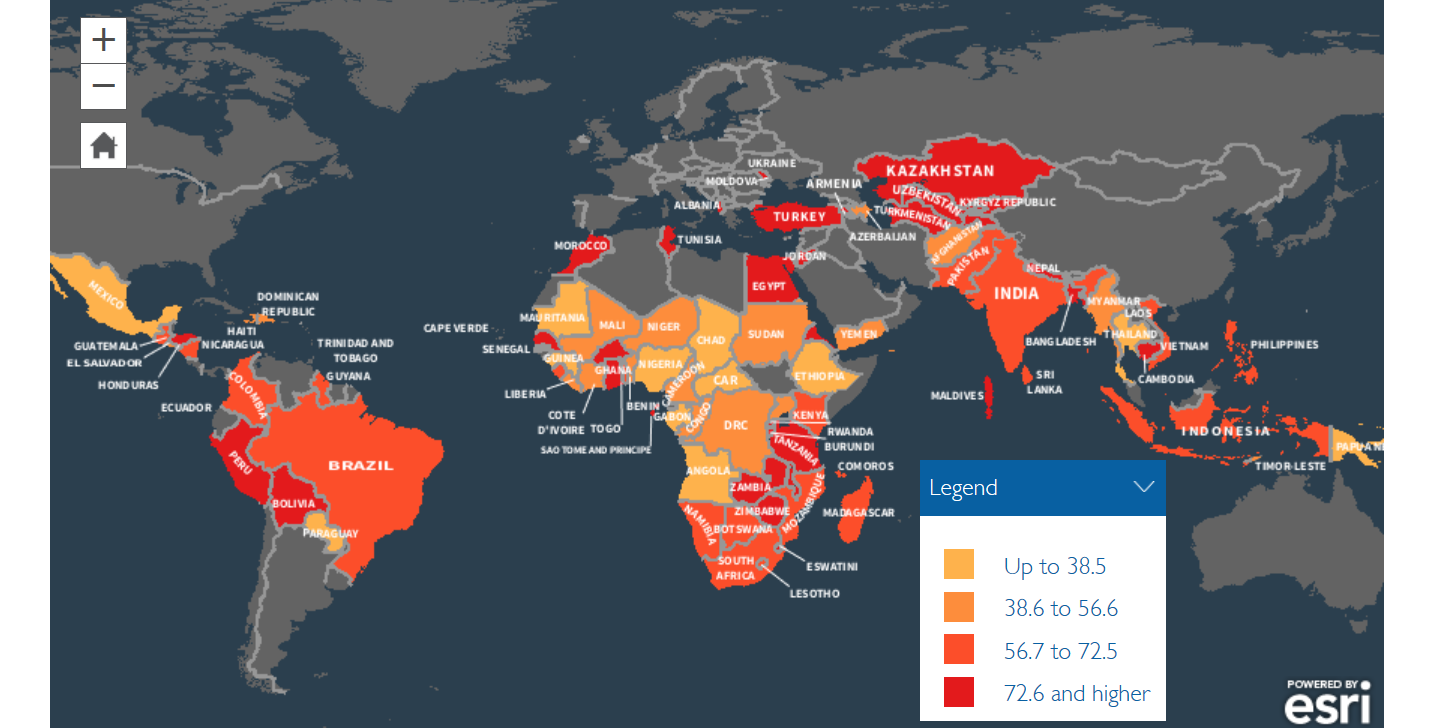

COVID-19 has disrupted several child health services. Declines in institutional deliveries in low- and middle-income countries, mean that children are less likely to be formally assessed by health professionals following their birth, which will result in an increased risk to mortality (death) and morbidity (disease). Other factors that could contribute to preventable child deaths stems from disruptions to immunisation programmes in several countries especially those where less than 56% of children receive basic vaccinations as seen in the Figure 2 particularly in Africa and Mexico. All these disruptions are likely to interrupt the progress aimed to end preventable deaths of children including infants (up to 1 years old). If the COVID-19 disruptions continue, it is extremely unlikely that neonatal mortality will be reduced to at least as low as 12 per 1000 live births and under-5 mortality to at least as low as 25 per 1000 live births across the globe by 2030 .

Figure 2: Percentage of children 10-23 months in low and middle income countries (LMICs) who received all 8 basic vaccinations which are BCG (Bacille Calmette-Guérin, Anti-tuberculosis vaccine), 3 doses of DPT (Diphtheria, Pertussis, Tetanus) containing vaccine, 3 doses of polio vaccine (excluding polio vaccine given at birth), and 1 dose of MCV (Measles containing vaccine).

Source: Statcompiler

3: Massive reductions in screening and care for non-communicable diseases

The goal of reducing premature mortality from non-communicable diseases (NCDs) by one third is likely to be impacted by COVID-19. This is especially likely given the reduced screening provided in countries and regions that already report poor and late screening, that then directly contributes to higher cancer mortality. Most LMICs reported poor screening prior to COVID. Screening can detect early signs of cancer that can result in treatment that have higher likelihood of success and survival. For example, as seen in the Figure 3 which presents the percentage of women aged 15-49 who have breast and cervix screening in India in 2015/16, only 22% of women aged 15-49 have had a cervical examination and only 9.8% of women aged 15-49 underwent a breast examination in India. The screening prevalence is also poorer in Indian women aged 35-49 given that only 13% and 30% in this group underwent screening for breast or cervical cancer. In countries where there is national coverage of cervical screening like in the UK, all women between the aged of 25 and 64 are invited for screening with efficacy set at 75% of screening (Nuffield Trust, 2020).

Source: National Family Health Survey-4 of India National report

Work is being undertaken to address issues of salience in relation to NCDs. For instance, several researchers at The Open University are exploring ways of handling NCD’s either through linking industrial and social innovation to increase access to cancer care in East Africa (Professor Maureen Mackintosh) or by increasing screening for depression for people with diabetes and depression in Sub-Saharan Africa to improve treatment outcomes (Professor Cathy Lloyd and myself). The prevalence of screening and quality of care for cancer, diabetes and depression has further worsened due to COVID-19 which will make it difficult for LMICs to reduce premature mortality from non-communicable diseases by one third by 2030.

4: Challenges to universal health coverage

Target 3.8 of SDG3 aims to achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all. Health systems across the world were not functioning very well for those with limited financial means prior to COVID-19, due to ‘out of pocket expenditure’ (payments made by individuals for the use of health care) especially among poor people and an overall lack of hospital beds (especially intensive care beds). Health infrastructure globally has been completely overwhelmed, especially in countries and areas that are struggled with particularly high COVID-19 infection rates. It was very hard to accommodate COVID-19 patients in public health systems, pushing many people to visit private hospitals that charge high amounts for treatment and care. COVID-19 has demonstrated that the private model of health (i.e. health system relying mostly on for cost services) totally failed in a number of countries due to private hospitals electing to not treat COVID-19 patients. Those hospitals that were open were charging a premium in terms of fees, which pushed those that could barely afford this into poverty. These hospitals were mostly unmonitored for their quality of care, cost or their strategy to allocating beds to COVID-19 and non COVID-19 patients.

5: Health capacity challenges

One of the aims of SDG3 is to strengthen the capacity of all countries for early warning, risk reduction and management of national and global health risks. COVID-19 has already severely impacted on the economies of nations and regions across the planet and this will reduce allocation of internal funding to the respective health sectors. Given that high income countries, like the UK, are also facing financial challenges due to COVID-19, the global development assistance money high income countries provide is likely to be reduced. This in turn could further dampen drives aimed at improving health capacity of low- and middle-income countries.

In summary, COVID-19 has already impacted global health and will continue to impact on the SDG3 targets. A solution is to have a planet-wide strategic collaboration, which will need to start with vigorous test and trace systems to address COVID-19, in addition to a willingness to fight the COVID-19 pandemic in a consolidated manner until we have a COVID-19 vaccine. Once under control, and with concerted efforts, the lost ground in relation to SDG3 can be regained.

Rate and Review

Rate this article

Review this article

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews